M Ak in G G Roce Rie S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection Uarterly

VOLUME XXXVI The Historic New Orleans NUMBERS 2–3 SPRING–SUMMER Collection uarterly 2019 Shop online at www.hnoc.org/shop VIEUX CARRÉ VISION: 520 Royal Street Opens D The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly ON THE COVER The newly expanded Historic New Orleans B Collection: A) 533 Royal Street, home of the Williams Residence and Louisiana History Galleries; B) 410 Chartres Street, the Williams Research Center; C) 610 Toulouse Street, home to THNOC’s publications, marketing, and education departments; and D) the new exhibition center at 520 Royal Street, comprising the Seignouret- Brulatour Building and Tricentennial Wing. C D photo credit: ©2019 Jackson Hill A CONTENTS 520 ROYAL STREET /4 Track the six-year planning and construction process of the new exhibition center. Take an illustrated tour of 520 Royal Street. Meet some of the center’s designers, builders, and artisans. ON VIEW/18 THNOC launches its first large-scale contemporary art show. French Quarter history gets a new home at 520 Royal Street. Off-Site FROM THE PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT COMMUNITY/28 After six years of intensive planning, archaeological exploration, and construction work, On the Job: Three THNOC staff members as well as countless staff hours, our new exhibition center at 520 Royal Street is now share their work on the new exhibition open to the public, marking the latest chapter in The Historic New Orleans Collection’s center. 53-year romance with the French Quarter. Our original complex across the street at 533 Staff News Royal, anchored by the historic Merieult House, remains home to the Williams Residence Become a Member and Louisiana History Galleries. -

Saint Denis in New Orleans

A SELF-GUIDED WALKING TOUR OF NEW ORLEANS & THE LOCATIONS THAT INSPIRED RED DEAD REDEMPTION 2 1140 Royal St. 403 Royal St. Master Nawak Master Nawak We start at Bastille In the mission “The Joys Next up is the Lemoyne the RDR2 storyline. Saloon, the lavish, of Civilization”, Arthur National Bank, a grand three-storied social Morgan stops here to and impressive In the mission, The Louisiana State Bank epicenter of Saint gather intel on Angelo The infamous LaLaurie representation of the “Banking, The Old serves as a real life mirror Denis, made exclusive Bronte, the notorious Mansion is a haunted largest developed city American Art”, Dutch landmark in the French to its fictitious counterpart to the upper echelons of Italian crime lord of in the country. and Hosea round up the Quarter. Madame LaLaurie in both design and purpose. gang for one last heist, society by its wealthy, Saint Denis. He is was a distinguished Creole According to Wikipedia, “the Established in 1763, a final attempt to well-to-do patrons. cautioned by the wary socialite in the early 1800’s, Louisiana State Bank was bartender to abandon later discovered to be a Saint Denis’ stateliest procure the cash they founded in 1818, and was Will you: play a dangerous waters... serial killer and building is older than need in order to start the first bank established in spirited, high-stakes slave torturer. the country itself. over as new men in a the new state of Louisiana game of poker with a This is also the only When her despicable crimes Heiresses and captains free world. -

Garden District Accommodations Locator

GARDEN DISTRICT ACCOMMODATIONSJefferson LOCATOR Leontine Octavia BellcastleValmont Duffosat MAP #/PROPERTY/NUMBER OF ROOMS Soniat MAGAZINE Robert GARDEN DISTRICT/UPTOWN STREET LyonsUpperline 1. Avenue Plaza Resort/50 Bordeaux 2. Best Western St. Charles Inn/40 Valence 3. Columns Hotel/20 Cadiz 4. Hampton Inn – Garden District/100 Jena 5. Hotel Indigo New Orleans - Garden District/132 Tchoupitoulas 6. Maison St. Charles Quality Inn & Suites/130 General PershingNapoleonUPTOWN 7. Prytania Park Hotel/90 Marengo Milan Annunciation Laurel Camp Constance GEOGRAPHY ConstantinopleChestnut Coliseum New Orleans encompasses 4,190 square miles or Austerlitz Perrier Gen. Taylor Prytania 10,850 square kilometers and is approximately 90 Pitt Peniston miles from the mouth of the Mississippi River. Carondelet Amelia St.Charles Av Magazine Baronne Antonine CLIMATE Foucher 3 2 New Orleans has a subtropical climate with pleasant Aline 4 year-round temperatures. Temperatures range from Delachaise mid-40°F (7°C) in winter to more than 90°F (32°C) ST. CHARLES in the summer. Rainfall is common in New Orleans, Louisiana with a monthly average of about five inches (12.7 cm) Toledano AVENUE Pleasant of precipitation. 9th Harmony 8th AVERAGE TEMPERATURES AVG. RAINFALL MONTH MAX {°F/°C} MIN {°F/°C} 7th {IN/CM} Camp Jan. 63/17 43/6 4.9/12.4 6th Chestnut Prytania Coliseum Constance Feb. 64/18 45/7 5.2/13.2 Magazine Conery March 72/22 52/11 4.7/11.9 Washington April 79/26 59/15 4.5/11.4 GARDEN 4th May 84/29 64/18 5.1/13.0 June 90/32 72/22 4.6/11.7 DISTRICT 3rd July 91/33 73/23 6.7/17.0 2nd S. -

MACCNO Street Performer's Guide

Know your stories background In 1956 a Noise ordinance was implemented to dictate... Through a rights when I’m a full time resident of the French Quarter who series of amendments and changes the ordinance is struggling would like to see more opportunities for our musicians to reach a healthy balance which respects residents while both on the street and in the restaurants and clubs. preserving New Orleans’ historic and unique music culture. performing: Street musicians are an integral part of the Quarter *Taken from the New Orleans Code of Ordinances and appreciated by many including a lot of the residents. That said we do need to educate residents, GUIDE TO businesses and musicians about the complexities of . performing on the streets of the Quarter. With a little 1959 give and take by all stakeholders we should be able to First unified city code bans NEW ORLEANS peacefully co-exist and prosper in this unique part of musicians from playing on city in the City. streets from 8 pm to 9 pm. any public right of way, public park or recreational 1977 area as long as you don’t exceed an average of City ordinance prohibiting I’m a community organizer and a lifelong advocate street performance on STREET measured at from the source. for many of the cultural groups in this city. I believe 1981 Royal St declared (Sec 66-203) that groups like the Mardi Gras Indians, Social Aid Unified city code is amended unconstitutional. & Pleasure Clubs, and brass bands are not fully to include a noise policy that utilizes decibel sound levels. -

The Weather Is Turning Colder and the Days Are Getting

Calendar OF EVENTS DECEMBER 11/ 23-1/2 Miracle on Fulton St. 11/25-1/1 Celebration in the Oaks, New Orleans City Park 3 French Market’s Saint Nicholas Day Fair & Christmas Parade 3 Bonfire on the Levee , Oak Alley 5-16 Christmas Choirs @ Place St. Charles around the lobby fountain 8-9 Annual Holiday Arts & Crafts Fair @ Place St. Charles around the lobby fountain, 11 a.m. - 3 p.m. www.placestcharles.com 201 ST. CHARLES AVENUE • DeceMBer 2011 11 Caroling in Washington Square 18 Caroling in Jackson Square 24 Christmas Eve Bonfires on Levee The weather is turning colder and the days CLAY CREATIONS 25 MERRY CHRISTMAS! are getting shorter, it’s beginning (finally!) interprets local architec- to feel a lot like Christmas! Hearts swell ture in clay. Have your 31 New Year’s Eve French Quarter The Celebration & Fireworks with feelings of good will towards others and for a own house or another brief moment, we give ourselves permission to let go edifice immortalized in clay. of all the little stressors that constrain us and open Many popular facades are JANUARY 2012 our hearts to love... the joy of giving and receiving. already available. 1 HAPPY NEW YEAR! Christmas is simply a magical season. Place St. Charles NANCY EAVES creates un- 3 Allstate Sugar Bowl celebrates the magic with their Annual HOLIDAY usual jewelry, one piece at a time, 4-2/21 Mardi Gras Parades ARTS & CRAFTS FAIR held Thursday, December 8 using antique and found objects combined and Friday, December 9 from 11 a.m. -

FMC Flea and Farmers Market Study Appendix

French Market Flea & Farmers Market Study Appendix This appendix includes all of the documents produced during the engagement and study process for the French Market. Round 1 Engagement Summary Round 2 Engagement Summary ROUND 1 STAKEHOLDER ROUND 2 STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT SUMMARY ENGAGEMENT SUMMARY Vendor Meeting Jan. 21, 8-10 AM Public Virtual Meeting Public Virtual Meeting February 25, 6-7 PM Jan. 21, 6-8 PM Public Survey Culture Bearer Meeting February 25 - March 12 Feb. 11, 12-1 PM Round 3 Engagement Summary Public Bathing Research Document Round 3 Stakeholder ADDENDUM: PUBLIC TOILETS AND SHOWERS Engagement Takeaways Bathrooms at the French Market Stakeholders offered the following feedback after reviewing preliminary recommendations for each category: Findings about plumbing, public toilets and showers Policy Research findings: • Provide increased support for janitorial staff and regular, deep cleaning of bathrooms and facilities • Estate clear policies and coordination needed for vendor loading and parking An initial search into public hygiene facilities has yielded various structures • Incentivize local artists to be vendors by offering rent subsidies for local artist and artisan vendors who hand-make their products. and operating models, all of which present opportunities for addressing • Designate a specific area for local handmade crafts in the market, that is separate from other products so the FMC’s desire to support its vendors, customers, and the surrounding community. customers know where to find them. • Vendor management software and apps work for younger vendors but older vendors should be able to Cities, towns, municipalities and non-profit organizations, alone and in partnership, have access the same information by calling or talking to FMC staff in person. -

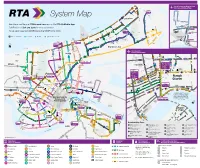

System Map 63 Paris Rd

Paris Rd. 60 Morrison Hayne 10 CurranShorewood Michoud T 64, 65 Vincent Expedition 63 Little Woods Paris Rd. Michoud Bullard North I - 10 Service Road Read 62 Alcee Fortier Morrison Lake Pontchartrain 17 Vanderkloot Walmart Paris Rd. T 62, 63, Lake Forest Crowder 64, 65 510 Dwyer Louis Armstrong New Orleans Lakefront Bundy Airport Read 63 94 60 International Airport Map Bullard Hayne Morrison US Naval 16 Joe Yenni 65 Joe Brown Reserve 60 Morrison Waterford Dwyer 64 Hayne 10 Training Center North I - 10 Service Road Park Michoud Old Gentilly Rd. Michoud Lakeshore Dr. Springlake CurranShorewood Bundy Pressburg W. Loyola W. University of SUNO New Orleans East Hospital 65 T New Orleans Downman 64, 65 T 57, 60, 80 62 H Michoud Vincent Loyola E. UNO Tilford Facility Expedition 80 T 51, 52, Leon C. Simon SUNO Lake Forest64 Blvd. Pratt Pontchartrain 55, 60 Franklin Park Debore Harbourview Press Dr. New Orleans East Williams West End Park Dwyer 63 Academy Robert E. Lee Pressburg Park s Paris St. Anthony System Map 63 Paris Rd. tis Pren 45 St. Anthony Odin Little Woods 60 10 H Congress Michoud Gentilly 52 Press Bullard W. Esplanade Bucktown Chef Menteur Hwy. Fillmore Desire 90 57 65 Canal Blvd. Mirabeau 55 32nd 51 Old Gentilly Bonnabel 15 See Interactive Maps at RTAforward.com and on the RTA GoMobile App. Duncan Place City Park y. Chef Menteur / Desire North I - 10 Service Road 5 Hw 62 Pontchartrain Blvd. Harrison Gentilly 94 ur Read 31st To Airport Chef Mente T 62, 63, 64, 65, 80, 94 Alcee Fortier 201 Clemson 10 Gentilly To Downtown MetairieMetairie Terrace Elysian Fields Fleur de Lis Lakeview St. -

Hibernia National Bank Collection RG 527 Louisiana State Museum Historical Center August 2013

1 Hibernia National Bank Collection RG 527 Louisiana State Museum Historical Center August 2013 Descriptive Summary Provenance: Gift from Capitol One Bank Title: Hibernia National Bank Collection Dates: 1870 - 2006 Abstract: This collection of Hibernia National Bank objects covers its rich history ranging from the time that it was established in New Orleans to when it was acquired by the Capitol One Bank, 1873- 2006. The collection contains photographs, newspaper clippings, staff memos, newsletter, and ledgers, along with original doorknobs, locks, mailboxes, stamps, and safety deposit key chains (located in SciTech). [Source: LSM acquisitions records]. Extent: 26 boxes Accession: 2008.075.05.001-.114; 2012.055.001-.1669 ______________________________________________________________________ Biographical / Historical Note Hibernia National Bank was founded in 1870 as a personal banking and commercial lending institution headquartered in NEW Orleans, LA. It was the largest and oldest bank headquartered in Louisiana, with other locations in Texas, Mississippi, and Arkansas. In March 2005, it was announced that the Capitol One Financial Corporation would be acquiring Hibernia National Bank for $5.3 billion. The acquisition was set to close in September; however, just a few days before the deal was to be completed, Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans – Hibernia’s headquarters and biggest market. Capital One later agreed to acquire Hibernia at a lower price (approximately $5.0 billion), reflecting Hibernia’s lower value The bank became a wholly owned subsidiary of Capital One Financial Corporation in November 2005, and is now known as Bank South within Capital One. Capital One replaced the Hibernia name and brand with its own on April 24, 2006. -

Than 200 Performances on 19 Stages Tank & the Bangas, Irma Thomas, Soul Rebels, Kermit Ruffins Plus More Than 20 Debuts Including Rickie Lee Jones

French Quarter Festivals, Inc. 400 North Peters, Suite 205 New Orleans, LA 70130 Contact: Rebecca Sell phone: 504-522-5730 cell: 504-343-5559 email: [email protected] __________________________________________________________________________________________ FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE French Quarter Festival presented by Chevron Returns as a Live Event September 30 – October 2, 2021! Special fall festival edition brings music, community, and celebration back to the streets! New Orleans (June 15, 2021)— The non-profit French Quarter Festivals, Inc. (FQFI) is excited to announce the return of French Quarter Festival presented by Chevron. Festival organizers didn’t want to let another calendar year pass without bringing back this celebrated tradition and critical economic driver back for fans, musicians, and local businesses. The one-time-only fall edition of French Quarter Festival takes place September 30 – October 2 across venues and stages in the French Quarter neighborhood. Attendees will experience the world’s largest celebration of Louisiana’s food, music, and culture during the free three-day event. As New Orleans makes its comeback, fall 2021 will deliver nearly a year’s-worth of events in a few short months. At the City's request, FQFI organizers have consolidated festival activities into an action-packed three-days in order allow the city to focus its security and safety resources on the New Orleans Saints home game on Sunday, October 3. FQFI has shifted programming in order to maximize the concentrated schedule and present time-honored festival traditions, stages, and performances. The event will bring regional cuisine from more than 50 local restaurants, hundreds of Louisiana musicians on 19 stages, and special events that celebrate New Orleans’ diverse, unique culture. -

Where the Locals Go

Where The Locals Go Stone Pigman's Top New Orleans Picks Where The Locals Go 1 The lawyers of Stone Pigman Walther Wittmann L.L.C. welcome you to the great city of New Orleans. Known around the world for its food, nightlife, architecture and history, it can be difficult for visitors to decide where to go and what to do. This guide provides recommendations from seasoned locals who know the ins-and-outs of the finest things the city has to offer. "Antoine’s Restaurant is the quintessential classic New Orleans restaurant. The oldest continuously operated family owned restaurant in the country. From the potatoes soufflé to the Baked Alaska with café Diablo for dessert, you are assured a memorable meal." (713 St. Louis Street, New Orleans, LA 70130 (504) 581-4422) Carmelite Bertaut "My favorite 100+ year old, traditional French Creole New Orleans restaurant is Arnaud’s. It's a jacket required restaurant, but has a causal room called the Jazz Bistro, which has the same menu, is right on Bourbon Street, and has a jazz trio playing in the corner of the room." (813 Bienville Avenue, New Orleans, LA 70112 (504) 523-5433) Scott Whittaker "The food at Atchafalaya is delicious and the brunch is my favorite in the city. The true standout of the brunch is their build-your-own bloody mary bar. It has everything you could want, but you must try the bacon." (901 Louisiana Avenue, New Orleans, LA 70115 (504) 891-9626) Maurine Wall "Chef John Besh’s restaurant August never fails to deliver a memorable fine dining experience. -

Strategic Master Plan to Exceed the Needs of Tomorrow

Port NOLA FORWARD A Strategic Master Plan to Exceed the Needs of Tomorrow May 2018 FROM THE PRESIDENT AND CEO Together with the Board of The plan presents a menu of strategies clear, wide guidelines to capitalize on our Commissioners of the Port of New to optimize current assets and extend gateway position rather than prescriptive Orleans, I am pleased to share Port our reach across all business lines. land use mandates. In fact, while we NOLA’s bold vision to deliver significant, were developing the plan, we acted on its The crux of this plan—and a necessary sustained economic benefit throughout promise and increased our multimodal ingredient for its success—is our jurisdiction, which includes Jefferson, strength with the acquisition of the New collaborative partnership with a wide Orleans, and St. Bernard Parishes. Orleans Public Belt. Access to six Class I range of stakeholders, broadly defined. This will be accomplished by providing railroads is a competitive advantage, now Throughout the planning process, we necessary infrastructure and seamless secured. This new alignment occurred invited the participation of our tenants, logistics solutions that incorporate the during the planning process, after we carriers, customers, Federal, State Brandy D. Christian industry’s changing needs and exceed had completed the market analysis and President and CEO, and local elected officials, economic our customers’ expectations. infrastructure evaluation, and has set the Port of New Orleans and development and civic leaders, and New Orleans Public Belt stage for our vision of building a multi- This Strategic Master Plan challenges us our neighbors, residents who rely on Railroad Corporation modal gateway. -

The 610 Stompers of New Orleans: Mustachioed Men Making a Difference Through Dance Nikki M

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 The 610 Stompers of New Orleans: Mustachioed Men Making a Difference Through Dance Nikki M. Caruso Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF VISUAL ARTS, THEATRE AND DANCE THE 610 STOMPERS OF NEW ORLEANS: MUSTACHIOED MEN MAKING A DIFFERENCE THROUGH DANCE By NIKKI M. CARUSO A Thesis submitted to the School of Dance in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2014 © 2014 Nikki M. Caruso Nikki M. Caruso defended this thesis on April 4, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jennifer Atkins Professor Directing Thesis Tricia Young Committee Member Ilana Goldman Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .........................................................................................................................v ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER ONE: “The Rise of the 610 Stompers: ‘Oh How I Want