(145) the Spring Migration, 1930, at the Cambridge Sewage Farm. by David L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Species Account

SPOTTED SANDPIPER Actitis macularius non-breeding visitor, vagrant monotypic Spotted Sandpipers breed across n. N America and winter as far south as c. S America (AOU 1998). The status of this species in the Pacific and the Hawaiian Islands is confused by its similarity to Common Sandpiper, a Eurasian counterpart (Dement'ev and Gladkov 1951c, Cramp and Simmons 1983), that has reached the Hawaiian Islands on at least two occasion and possibly others (David 1991). Records of this pair, unidentified to species, have been reported throughout the Pacific (E 41:115, Clapp 1968a, Pyle and Engbring 1985, Pratt et al. 1987) while confirmed Spotted Sandpipers have been recorded from Clipperton, the Marshall, Johnston, and the Hawaiian Is (Amerson and Shelton 1976, Howell et al. 1993, AOU 1998). David (1991) analyzed records of the two species of Actitis sandpipers in the Southeastern Hawaiian Islands and concluded that, between 1975 and 1989, 6 of 12 birds (1983-1989) could be confirmed as Spotted Sandpipers based on descriptions and photographs while the remaining six (1975-1983) could not be identified. Prior to this, Pyle (1977) listed only the species pair (Spotted/Common Sandpiper) for the Hawaiian Islands. Since this analysis and through the 2000s there have been 25 additional records of Actitis, 18 of which we consider confirmed Spotted Sandpipers while 7 did not include enough descriptive notes to separate them from Common Sandpiper. Because 24 of 37 records in the Southeastern Islands have been confirmed as Spotted Sandpipers and only one has been confirmed as a Common Sandpiper, we assume that the following summary of Actitis sandpipers reflects the status of Spotted Sandpiper, the more expected species in the Southeastern Islands. -

<I>Actitis Hypoleucos</I>

Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos M. NICOLL 1 & P. KEMP 2 •c/o DundeeMuseum, Dundee, Tayside, UK 243 LochinverCrescent, Dundee, Tayside, UK Citation: Nicoll, M. & Kemp, P. 1983. Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos. Wader Study Group Bull. 37: 37-38. This note is intended to draw the attention of wader catch- and the old inner feathersare often retained (Pearson 1974). ers to the needfor carefulexamination of the primariesof Similarly, in Zimbabwe, first-year Common Sandpipers CommonSandpipers Actiris hypoleucos,and other waders, replacethe outerfive to sevenprimaries between December for partial primarywing moult. This is thoughtto be a diag- andApril (Tree 1974). It thusseems normal for first-spring/ nosticfeature of wadersin their first spring and summer summerCommon Sandpipers wintering in eastand southern (Tree 1974). Africa to show a contrast between new outer and old inner While membersof the Tay Ringing Group were mist- primaries.There is no informationfor birdswintering further nettingin Angus,Scotland, during early May 1980,a Com- north.However, there may be differencesin moult strategy mon Sandpiperdied accidentally.This bird was examined betweenwintering areas,since 3 of 23 juvenile Common and measured, noted as an adult, and then stored frozen un- Sandpiperscaught during autumn in Morocco had well- til it was skinned,'sexed', andthe gut contentsremoved for advancedprimary moult (Pienkowski et al. 1976). These analysis.Only duringskinning did we noticethat the outer birdswere moultingnormally, and so may have completed primarieswere fresh and unworn in comparisonto the faded a full primary moult during their first winter (M.W. Pien- and abradedinner primaries.The moult on both wingswas kowski, pers.comm.). -

Actitis Hypoleucos

Actitis hypoleucos -- Linnaeus, 1758 ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- CHARADRIIFORMES -- SCOLOPACIDAE Common names: Common Sandpiper; Chevalier guignette European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Van den Bossche, W., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Near Threatened (NT) In Europe this species has an extremely large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence <20,000 km2 combined with a declining or fluctuating range size, habitat extent/quality, or population size and a small number of locations or severe fragmentation). The population size is extremely large, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population size criterion (<10,000 mature individuals with a continuing decline estimated to be >10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). Despite the fact that the population trend appears to be decreasing, the decline is not believed to be sufficiently rapid to approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the population trend criterion (>30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in Europe. In the EU27 the species has undergone moderately rapid declines and is therefore classified as Near Threatened under Criterion A (A2abc+3bc+4abc). Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Albania; Andorra; Armenia; Austria; Azerbaijan; Belarus; Belgium; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bulgaria; Croatia; Cyprus; Czech Republic; Denmark; Estonia; Finland; France; Georgia; Germany; Greece; Hungary; Ireland, Rep. -

Ageing and Sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis Hypoleucos

ageing & sexing series Wader Study 122(1): 54 –59. 10.18194/ws.00009 This series summarizing current knowledge on ageing and sexing waders is co-ordinated by Włodzimier Meissner (Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Department of Vertebrate Ecology & Zoology, University of Gdansk, ul. Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdansk, Poland, [email protected]). See Wader Study Group Bulletin vol. 113 p. 28 for the Introduction to the series. Part 11: Ageing and sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos Włodzimierz Meissner 1, Philip K. Holland 2 & Tomasz Cofta 3 1Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Department of Vertebrate Ecology & Zoology, University of Gdańsk, ul.Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdańsk, Poland. [email protected] 232 Southlands, East Grinstead, RH19 4BZ, UK. [email protected] 3Hoene 5A/5, 80-041 Gdańsk, Poland. [email protected] Meissner, W., P.K. Holland & T. Coa. 2015. Ageing and sexing series 11: Ageing and sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos . Wader Study 122(1): 54 –59. Keywords: Common Sandpiper, Actitis hypoleucos , ageing, sexing, moult, plumages The Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos is treated as were validated using about 500 photographs available on monotypic through a breeding range that extends from the Internet and about 50 from WRG KULING ringing Ireland eastwards to Japan. Its main non-breeding area is sites in northern Poland. also vast, reaching from the Canary Islands to Australia with a few also in the British Isles, France, Spain, Portugal MOULT SCHEDULE and the Mediterranean (Cramp & Simmons 1983, del Juveniles and adults leave the breeding grounds as soon Hoyo et al. 1996, Glutz von Blotzheim et al. -

Hatching Dates for Common Sandpiper <I>Actitis Hypoleucos</I

Hatching dates for Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos chicks - variation with place and time T.W. Dougall, P.K. Holland& D.W. Yalden Dougall,T.W., Holland,P.K. & Yalden, D.W. 1995. Hatchingdates for CommonSandpiper Actitishypoleucos chicks - variationwith place and time. WaderStudy Group Bull. 76: 53-55. CommonSandpiper chicks hatched in 1990-94between 24 May (year-day146) and 13 July (year-day196), butthe averagehatch-date was variablebetween years, up to 10 days earlier in 1990 than in 1991. There are indicationsthat on average CommonSandpipers hatch a few days earlierin the Borders,the more northerlysite, butthis may reflecta changein the age structureof the Peak Districtpopulation between the 1970sand the 1980s- 1990s,perhaps the indirectconsequence of the bad weatherof April 1981. Dougall,T. W., 29 LaudstonGardens, Edinburgh EH3 9HJ, UK. Holland,P. K., 2 Rennie Court,Brettargh Drive, LancasterLA 1 5BN, UK. Yalden,D. W., Schoolof BiologicalSciences, University, Manchester M13 9PT, UK. INTRODUCTION Yalden(1991a) in calculatingthe originalregression, and comingfrom the years 1977-1989 (mostlythe 1980s). CommonSandpipers Actitis hypoleucos have a short We also have, for comparison,the knownhatch dates for breedingseason, like mostwaders; arriving back from 49 nestsreported by Hollandet al. (1982), comingfrom West Africa in late April, most have laid eggs by mid-May, various sites in the Peak District in the 1970s. which hatch around mid-June. Chicksfledge by early July, and by mid-Julymost breedingterritories are Ringingactivities continue through the breedingseason at deserted(Holland et al. 1982). The timingof the breeding both sites, and chickscan be at any age from 0 to 19 days season seems constantfrom year to year, but there are old when caught (thoughyoung chicks are generally few data to quantifythis impression.It is difficultto locate easier to find). -

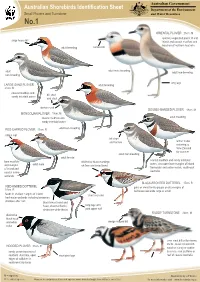

Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1

Australian Government Australian Shorebirds Identification Sheet Department of the Environment Small Plovers and Turnstone and Water Resources No.1 ORIENTAL PLOVER 25cm. M sparsely vegetated plains of arid large heavy bill inland and coastal mudflats and beaches of northern Australia adult breeding narrow bill adult male breeding adult adult non-breeding non-breeding long legs LARGE SAND PLOVER adult breeding 21cm. M coastal mudflats and bill short sandy intertidal zones and stout darker mask DOUBLE-BANDED PLOVER 19cm. M MONGOLIAN PLOVER 19cm. M coastal mudflats and adult breeding sandy intertidal zones RED-CAPPED PLOVER 15cm. R adult non-breeding rufous cap bill short and narrow winter visitor returning to New Zealand for summer adult non-breeding adult female coastal mudflats and sandy intertidal bare mudflats distinctive black markings zones, also open bare margins of inland and margins adult male on face and breastband of inland and freshwater and saline marsh, south-east coastal saline Australia wetlands BLACK-FRONTED DOTTEREL 17cm. R RED-KNEED DOTTEREL pairs or small family groups on dry margins of 18cm. R feshwater wetlands large or small feeds in shallow margins of inland short rear end freshwater wetlands including temporary shallows after rain black breast band and head, chestnut flanks, long legs with distinctive white throat pink upper half RUDDY TURNSTONE 23cm. M distinctive black hood and white wedge shaped bill collar uses stout bill to flip stones, shells, seaweed and drift- 21cm. R HOODED PLOVER wood on sandy or cobble sandy ocean beaches of beaches, rock platform or southern Australia, open short pink legs reef of coastal Australia edges of saltlakes in south-west Australia M = migratory . -

Green Sandpiper

Green Sandpiper The Green Sandpiper (Tringa ochropus) is a small wader of the Old World. The genus name Tringa is the New Latin name given to the Green Sandpiper by Aldrovandus in 1599 based on Ancient Greek trungas, a thrush-sized, white- rumped, tail-bobbing wading bird mentioned by Aristotle. The specific ochropus is from Ancient Greek okhros, "ochre", and pous, "foot". The Green Sandpiper represents an ancient lineage of the genus Tringa and its only close living relative is the Solitary Sandpiper (T. solitaria). They both have brown wings with little light dots and a delicate but contrasting neck and chest pattern. In addition, both species nest in trees, unlike most other scolopacids. Given its basal position in Tringa, it is fairly unsurprising that suspected cases of hybridisation between this species and the Common Sandpiper (A. hypoleucos) of the sister genus Actitis have been reported. This species is a somewhat plump wader with a dark greenish-brown back and wings, greyish head and breast and otherwise white underparts. The back is spotted white to varying extents, being maximal in the breeding adult, and less in winter and young birds. The legs and short bill are both dark green. It is conspicuous and characteristically patterned in flight, with the wings dark above and below and a brilliant white rump. The latter feature reliably distinguishes it from the slightly smaller but otherwise very similar Solitary Sandpiper (T. solitaria) of North America. It breeds across subarctic Europe and Asia and is a migratory bird, wintering in southern Europe, the Indian Subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and tropical Africa. -

Ultimate Papua New Guinea Ii

The fantastic Forest Bittern showed memorably well at Varirata during this tour! (JM) ULTIMATE PAPUA NEW GUINEA II 25 AUGUST – 11 / 15 SEPTEMBER 2019 LEADER: JULIEN MAZENAUER Our second Ultimate Papua New Guinea tour in 2019, including New Britain, was an immense success and provided us with fantastic sightings throughout. A total of 19 Birds-of-paradise (BoPs), one of the most striking and extraordinairy bird families in the world, were seen. The most amazing one must have been the male Blue BoP, admired through the scope near Kumul lodge. A few females were seen previously at Rondon Ridge, but this male was just too much. Several males King-of-Saxony BoP – seen displaying – ranked high in our most memorable moments of the tour, especially walk-away views of a male obtained at Rondon Ridge. Along the Ketu River, we were able to observe the full display and mating of another cosmis species, Twelve-wired BoP. Despite the closing of Ambua, we obtained good views of a calling male Black Sicklebill, sighted along a new road close to Tabubil. Brown Sicklebill males were seen even better and for as long as we wanted, uttering their machine-gun like calls through the forest. The adult male Stephanie’s Astrapia at Rondon Ridge will never be forgotten, showing his incredible glossy green head colours. At Kumul, Ribbon-tailed Astrapia, one of the most striking BoP, amazed us down to a few meters thanks to a feeder especially created for birdwatchers. Additionally, great views of the small and incredible King BoP delighted us near Kiunga, as well as males Magnificent BoPs below Kumul. -

The Population Biology of Common Sandpipers in Britain T

Ben Green The population biology of Common Sandpipers in Britain T. W. Dougall, P. K. Holland and D. W.Yalden Abstract The population biology of Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos has been studied, especially by colour-ringing breeding adults, at two sites, in the Peak District and in the Scottish Borders. Adults are usually site-faithful, males more so than females, contributing to a good apparent survival rate (72% and 67%, respectively). Some, at least, return to breed at one year old, but usually not to the site where they hatched. The population in Britain seems to be in slow decline, most obviously indicated by a contraction along the edges of its range, which results especially from poor recruitment of young birds. This does not seem to be due to poorer breeding success, but it is uncertain whether it is caused by a subtle effect of climate change, change in quality of stopover sites on migration, or changes in wintering habitat. Since we don’t know precisely where British birds spend the winter, the last possibility is especially hard to evaluate. Introduction or Wood Lark Lullula arborea, but not suffi- The Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos is ciently abundant to benefit from mass one of those ‘in between’ birds – not rare studies, like the Blue Tit Cyanistes caeruleus enough to have attracted devoted individual or Robin Erithacus rubecula. Unlike many attention, like the Osprey Pandion haliaetus waders, it does not flock in large numbers to 100 © British Birds 103 • February 2010 • 100–114 Common Sandpipers in Britain fields, estuaries or the Banc d’Arguin, it is not censused by moorland bird counts, and when on migration does not Howden get ringed in any great Reservoir numbers. -

(2007): Birds of the Aleutian Islands, Alaska Please

Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi OSPREYS FINCHES Osprey Ca Ca Ac Brambling I Ca Ca EAGLES and HAWKS Hawfinch I Ca Northern Harrier I I I Common Rosefinch Ca Eurasian Sparrowhawk Ac (Ac) Pine Grosbeak Ca Bald Eagle* C C C C Asian Rosy-Finch Ac Rough-legged Hawk Ac Ca Ca Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch* C C C C OWLS (griseonucha) Snowy Owl I Ca I I Gray-crowned Rosy-Finch (littoralis) Ac Short-eared Owl* R R R U Oriental Greenfinch Ca FALCONS Common Redpoll I Ca I I Eurasian Kestrel Ac Ac Hoary Redpoll Ca Ac Ca Ca Merlin Ca I Red Crossbill Ac Gyrfalcon* R R R R White-winged Crossbill Ac Peregrine Falcon* (pealei) U U C U Pine Siskin I Ac I SHRIKES LONGSPURS and SNOW BUNTINGS Northern Shrike Ca Ca Ca Lapland Longspur* Ac-C C C-Ac Ac CROWS and JAYS Snow Bunting* C C C C Common Raven* C C C C McKay's Bunting Ca Ac LARKS EMBERIZIDS Sky Lark Ca Ac Rustic Bunting Ca Ca SWALLOWS American Tree Sparrow Ac Tree Swallow Ca Ca Ac Savannah Sparrow Ca Ca Ca Bank Swallow Ac Ca Ca Song Sparrow* C C C C Cliff Swallow Ca Golden-crowned Sparrow Ac Ac Barn Swallow Ca Dark-eyed Junco Ac WRENS BLACKBIRDS Pacific Wren* C C C U Rusty Blackbird Ac LEAF WARBLERS WOOD-WARBLERS Bold* = Breeding Sp Su Fa Wi Wood Warbler Ac Yellow Warbler Ac Dusky Warbler Ac Blackpoll Warbler Ac DUCKS, GEESE and SWANS Kamchatka Leaf Warbler Ac Yellow-rumped Warbler Ac Emperor Goose C-I Ca I-C C OLD WORLD FLYCATCHERS "HYPOTHETICAL" species needing more documentation Snow Goose Ac Ac Gray-streaked Flycatcher Ca American Golden-plover (Ac) Greater White-fronted Goose I -

Behaviour of an Incubating Woodcock G

Behaviour of an incubating Woodcock G. des Forges INTRODUCTION In his well-known paper on the breeding habits of the'Woodcock Scolopax rusticola, Steinfatt (1938) records: 'The brooding female only rarely changes her position during the day; she lies for hours on the nest motionless. There seems to be a sort of rigidity, which overcomes the female. It obviously serves the purpose to reduce smell and so the possibility of being observed. Only twice a day, in morning and evening twilight, the female leaves the nest, in order to find food, for a total time of an hour'. A report on the European Woodcock (Shorten 1974) states that 'Steinfatt's description of behaviour at the nest seems to have been the basis for many subse quent accounts'. Also Vesey-Fitzgerald (1946), writing of his own experience in Surrey, says, 'I do not think that, unless disturbed, a sitting Woodcock leaves the nest during the day'. As circumstantial evidence had led me to believe that a sitting Woodcock did leave the nest and feed by day, I decided to attempt a prolonged watch on an incubating bird. THE NEST SITE The nest was in woodland, about 5 km north of Haywards Heath, West Sussex, on a hill-side sloping down from the main London to Brighton railway line to a stream at the bottom of the valley. The section of the wood concerned had been cleared of undergrowth and mature ash Fraxinus excelsior in 1972/73 leaving only standard oaks Quercus. Re-planting with mixed conifers had taken place in 1973/74 m tne open areas but not immediately round the nest, which was under the canopy of a group of six mature oaks, the lowest branches being 5 or 6 metres from the ground which here carried a thin growth of brambles Rubus fruticosus and bracken Pteridium aquilinum: but around the small conifers were only short grasses and a variety of perennials which had not made much growth by the end of March. -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION.