Interest at That Time Was Largely Provoked by Campaigns for Gp Right

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uk Government and Special Advisers

UK GOVERNMENT AND SPECIAL ADVISERS April 2019 Housing Special Advisers Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under INTERNATIONAL 10 DOWNING Toby Lloyd Samuel Coates Secretary of State Secretary of State Secretary of State Secretary of State Deputy Chief Whip STREET DEVELOPMENT Foreign Affairs/Global Salma Shah Rt Hon Tobias Ellwood MP Kwasi Kwarteng MP Jackie Doyle-Price MP Jake Berry MP Christopher Pincher MP Prime Minister Britain James Hedgeland Parliamentary Under Parliamentary Under Secretary of State Chief Whip (Lords) Rt Hon Theresa May MP Ed de Minckwitz Olivia Robey Secretary of State INTERNATIONAL Parliamentary Under Secretary of State and Minister for Women Stuart Andrew MP TRADE Secretary of State Heather Wheeler MP and Equalities Rt Hon Lord Taylor Chief of Staff Government Relations Minister of State Baroness Blackwood Rt Hon Penny of Holbeach CBE for Immigration Secretary of State and Parliamentary Under Mordaunt MP Gavin Barwell Special Adviser JUSTICE Deputy Chief Whip (Lords) (Attends Cabinet) President of the Board Secretary of State Deputy Chief of Staff Olivia Oates WORK AND Earl of Courtown Rt Hon Caroline Nokes MP of Trade Rishi Sunak MP Special Advisers Legislative Affairs Secretary of State PENSIONS JoJo Penn Rt Hon Dr Liam Fox MP Parliamentary Under Laura Round Joe Moor and Lord Chancellor SCOTLAND OFFICE Communications Special Adviser Rt Hon David Gauke MP Secretary of State Secretary of State Lynn Davidson Business Liason Special Advisers Rt Hon Amber Rudd MP Lord Bourne of -

Daily Report Tuesday, 1 September 2020 CONTENTS

Daily Report Tuesday, 1 September 2020 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 1 September 2020 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:30 P.M., 01 September 2020). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 10 Energy Supply: Electric ATTORNEY GENERAL 10 Vehicles 17 Crown Prosecution Service: Foreign Companies: China 18 Coronavirus 10 Furniture: Fire Resistant Emergency Services: Crimes Materials 18 of Violence 10 Galileo System 18 Retail Trade: Crimes of Green Homes Grant Scheme 19 Violence 11 New Businesses: Young Sentencing 11 People 19 Sexual Offences: Private OneWeb 20 Rented Housing 12 Oneweb: Investment 20 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Overseas Aid: Developing INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 12 Countries 21 Aerospace Industry: East Postgraduate Education: Midlands 12 Government Assistance 21 Aviation: Renewable Energy 13 Public Houses: Coronavirus 22 Batteries: Manufacturing Public Houses: Hospitality Industries 13 Industry 22 Business: Coronavirus 14 Redundancy Pay: Coronavirus Consumers: Credit 14 Job Retention Scheme 23 Coronavirus Job Retention Retail, Hospitality and Leisure Scheme 15 Grant Fund 23 Coronavirus: Vaccination 15 Small Businesses: Research 24 Department for Business, Universities: China 24 Energy and Industrial Strategy: Cabinet Office: Training 25 Ministerial Responsibility 16 Census: Sikhs 25 Disability: Coronavirus 16 Civil Servants: Coronavirus 25 Democracy -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Contents Theresa May - the Prime Minister

Contents Theresa May - The Prime Minister .......................................................................................................... 5 Nancy Astor - The first female Member of Parliament to take her seat ................................................ 6 Anne Jenkin - Co-founder Women 2 Win ............................................................................................... 7 Margaret Thatcher – Britain’s first woman Prime Minister .................................................................... 8 Penny Mordaunt – First woman Minister of State for the Armed Forces at the Ministry of Defence ... 9 Lucy Baldwin - Midwifery and safer birth campaigner ......................................................................... 10 Hazel Byford – Conservative Women’s Organisation Chairman 1990 - 1993....................................... 11 Emmeline Pankhurst – Leader of the British Suffragette Movement .................................................. 12 Andrea Leadsom – Leader of House of Commons ................................................................................ 13 Florence Horsbrugh - First woman to move the Address in reply to the King's Speech ...................... 14 Helen Whately – Deputy Chairman of the Conservative Party ............................................................. 15 Gillian Shephard – Chairman of the Association of Conservative Peers ............................................... 16 Dorothy Brant – Suffragette who brought women into Conservative Associations ........................... -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Stephen Kinnock MP Aberav

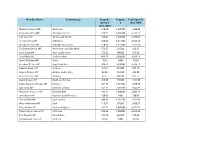

Member Name Constituency Bespoke Postage Total Spend £ Spend £ £ (Incl. VAT) (Incl. VAT) Stephen Kinnock MP Aberavon 318.43 1,220.00 1,538.43 Kirsty Blackman MP Aberdeen North 328.11 6,405.00 6,733.11 Neil Gray MP Airdrie and Shotts 436.97 1,670.00 2,106.97 Leo Docherty MP Aldershot 348.25 3,214.50 3,562.75 Wendy Morton MP Aldridge-Brownhills 220.33 1,535.00 1,755.33 Sir Graham Brady MP Altrincham and Sale West 173.37 225.00 398.37 Mark Tami MP Alyn and Deeside 176.28 700.00 876.28 Nigel Mills MP Amber Valley 489.19 3,050.00 3,539.19 Hywel Williams MP Arfon 18.84 0.00 18.84 Brendan O'Hara MP Argyll and Bute 834.12 5,930.00 6,764.12 Damian Green MP Ashford 32.18 525.00 557.18 Angela Rayner MP Ashton-under-Lyne 82.38 152.50 234.88 Victoria Prentis MP Banbury 67.17 805.00 872.17 David Duguid MP Banff and Buchan 279.65 915.00 1,194.65 Dame Margaret Hodge MP Barking 251.79 1,677.50 1,929.29 Dan Jarvis MP Barnsley Central 542.31 7,102.50 7,644.81 Stephanie Peacock MP Barnsley East 132.14 1,900.00 2,032.14 John Baron MP Basildon and Billericay 130.03 0.00 130.03 Maria Miller MP Basingstoke 209.83 1,187.50 1,397.33 Wera Hobhouse MP Bath 113.57 976.00 1,089.57 Tracy Brabin MP Batley and Spen 262.72 3,050.00 3,312.72 Marsha De Cordova MP Battersea 763.95 7,850.00 8,613.95 Bob Stewart MP Beckenham 157.19 562.50 719.69 Mohammad Yasin MP Bedford 43.34 0.00 43.34 Gavin Robinson MP Belfast East 0.00 0.00 0.00 Paul Maskey MP Belfast West 0.00 0.00 0.00 Neil Coyle MP Bermondsey and Old Southwark 1,114.18 7,622.50 8,736.68 John Lamont MP Berwickshire Roxburgh -

UK National Preventive Mechanism 2019-20 Annual Report

Monitoring places of detention Eleventh Annual Report of the United Kingdom’s National Preventive Mechanism 1 April 2019 – 31 March 2020 CP 366 Monitoring places of detention Eleventh Annual Report of the United Kingdom’s National Preventive Mechanism 1 April 2019 – 31 March 2020 Presented to Parliament by the Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice by Command of Her Majesty February 2021 CP 366 © Crown copyright 2021 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/official-documents and www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmiprisons/national-preventive-mechanism Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] or HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 3rd floor, 10 South Colonnade, Canary Wharf, London E14 4PU ISBN 978-1-5286-2373-5 CCS0121810850 02/21 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Contents Introduction by John Wadham, NPM Chair 4 1. Context 6 About the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT) 7 The UK’s National Preventive Mechanism 8 COVID-19 12 Political context, policy and legislative developments 13 Mental health and social care 15 Prisons 20 Children in detention 26 Immigration detention 31 Police custody 35 The situation in detention during the year 37 2. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 691 15 March 2021 No. 190 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 15 March 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. BORIS JOHNSON, MP, DECEMBER 2019) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY,MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE AND MINISTER FOR THE UNION— The Rt Hon. Boris Johnson, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Rishi Sunak, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN,COMMONWEALTH AND DEVELOPMENT AFFAIRS AND FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE— The Rt Hon. Dominic Raab, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Priti Patel, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. Michael Gove, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. Robert Buckland, QC, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Ben Wallace, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP COP26 PRESIDENT—The Rt Hon. Alok Sharma, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Kwasi Kwarteng, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE, AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Elizabeth Truss, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Dr Thérèse Coffey, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. -

Ministerial Departments CABINET OFFICE March 2021

LIST OF MINISTERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES Including Executive Agencies and Non- Ministerial Departments CABINET OFFICE March 2021 LIST OF MINISTERIAL RESPONSIBILITIES INCLUDING EXECUTIVE AGENCIES AND NON-MINISTERIAL DEPARTMENTS CONTENTS Page Part I List of Cabinet Ministers 2-3 Part II Alphabetical List of Ministers 4-7 Part III Ministerial Departments and Responsibilities 8-70 Part IV Executive Agencies 71-82 Part V Non-Ministerial Departments 83-90 Part VI Government Whips in the House of Commons and House of Lords 91 Part VII Government Spokespersons in the House of Lords 92-93 Part VIII Index 94-96 Information contained in this document can also be found on Ministers’ pages on GOV.UK and: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/government-ministers-and-responsibilities 1 I - LIST OF CABINET MINISTERS The Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP Prime Minister; First Lord of the Treasury; Minister for the Civil Service and Minister for the Union The Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP Chancellor of the Exchequer The Rt Hon Dominic Raab MP Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs; First Secretary of State The Rt Hon Priti Patel MP Secretary of State for the Home Department The Rt Hon Michael Gove MP Minister for the Cabinet Office; Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster The Rt Hon Robert Buckland QC MP Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice The Rt Hon Ben Wallace MP Secretary of State for Defence The Rt Hon Matt Hancock MP Secretary of State for Health and Social Care The Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP COP26 President Designate The Rt Hon -

Daily Report Tuesday, 15 December 2020 CONTENTS

Daily Report Tuesday, 15 December 2020 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 15 December 2020 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:46 P.M., 15 December 2020). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 7 Travel: Quarantine 15 ATTORNEY GENERAL 7 Utilities: Ownership 16 Food: Advertising 7 CABINET OFFICE 16 Immigration: Prosecutions 8 Consumer Goods: Safety 16 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND Government Departments: INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 9 Databases 16 Arcadia Group: Insolvency 9 Honours 16 Carbon Emissions 9 Prime Minister: Electric Climate Change 10 Vehicles 17 Coronavirus Job Retention DEFENCE 17 Scheme 10 Afghanistan and Iraq: Reserve Coronavirus: Disease Control 11 Forces 17 Employment: Coronavirus 11 Armed Forces: Coronavirus 18 Energy: Housing 11 Armed Forces: Finance 18 Facebook: Competition Law 12 Army: Training 19 Hospitality Industry: Autonomous Weapons 20 Coronavirus 13 Clyde Naval Base 20 Hydrogen: Garages and Petrol Defence: Procurement 21 Stations 13 Mali: Armed Forces 21 Public Houses: Wakefield 13 Military Aid 23 Regional Planning and Military Aircraft 23 Development 14 Ministry of Defence: Renewable Energy: Urban Recruitment 23 Areas 14 Reserve Forces 24 Sanitary Protection: Safety 14 Reserve Forces: Pay 25 Shops: Coronavirus 15 Reserve Forces: Training 25 Russia: Navy 26 Cattle Tracing System 39 Saudi Arabia: Military Aid 26 Cattle: Pneumonia 39 Unmanned -

A Rights-Based Analysis of Youth Justice in the United Kingdom

A RIGHTS-BASED ANALYSIS OF YOUTH JUSTICE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 2 A RIGHTS-BASED ANALYSIS OF YOUTH JUSTICE IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS Figures and tables Figure 1: Number of Children Referred to the Children’s Reporter in Scotland – 2006/07 to 2019/20 Figure 2: Children’s Hearing Panel – The Key Individuals Involved Figure 3: Key Demographic Data of Children in Scottish Secure Care - 2019 Figure 4: Number of First Time Entrants (FTEs) in Wales: 2009-2019 Figure 5: Rates of First Time Entrants (FTEs) in Wales: 2009 -2019 Figure 6: Swansea Number of First Time Entrants (FTEs) - Year Ending March 2009 to 2013 Figure 7: Non-Criminal Disposals (NCDs) as a Proportion of All Swansea Bureau Model Disposals. Administered 2009/10 to 2012/13 Figure 8: The Stages of the Trauma Recovery Model Figure 9: Permanent School Exclusions in Wales Figure 10: Fixed Term Exclusions (Over 5 Days) in Wales Figure 11: Number of First Time Entrants (FTEs) in England: 2009-2019 Table1: Children’s Reporter Decisions in Scotland – 2019/20 Table 2: Secure Care Provision in Scotland Table 3: Scottish School Exclusions (2006/07-2018/19) Table 4: Number of Arrests 2010-2018 by Welsh Police Service Area Table 5: Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility (MACR) Across Europe Table 6: Child Arrests by English Police Forces: 2010-2018 Table 7: Use of Force Incidents in English Secure Training Centres (STC) – Year Ending March 2019 Table 8: Number and Proportion of Arrests for Recorded Crime (Notifiable Offences) of Children by Self-Defined Ethnicity in English Police Force Areas Table 9: ‘Permanent’ and ‘Fixed Period’ School Exclusions in England – 2013/14 to 2018/19 Table 10: Juvenile Justice Centre (JJC) Demographic Data - 2018/19 CONTENTS FIGURES AND TABLES .................................................................................................. -

Boris's Government

BORIS’S GOVERNMENT CABINET Lord True, minister of state DEPARTMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION SCOTLAND OFFICE Rishi Sunak, chancellor of the exchequer Penny Mordaunt, paymaster general Elizabeth Truss, secretary of state for international trade; Gavin Williamson, secretary of state for education Alister Jack, secretary of state for Scotland Dominic Raab, first secretary of state, secretary of state for Chloe Smith, minister of state for the constitution and resident of the Board of Trade; minister for women Michelle Donelan, minister of state Douglas Ross, parliamentary under-secretary of state foreign and commonwealth affairs devolution and equalities Nick Gibb, minister of state for school standards Priti Patel, secretary of state for the home department Lord Agnew of Oulton, minister of state Conor Burns, minister of state Baroness Berridge, parliamentary under-secretary of state WALES OFFICE Michael Gove, chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster; minister Jacob Rees-Mogg, leader of the House of Commons; lord Greg Hands, minister of state Vicky Ford, parliamentary under-secretary of state Simon Hart, secretary of state for Wales for the Cabinet Office president of the council Graham Stuart, parliamentary under-secretary of state Gillian Keegan, parliamentary under-secretary of state David TC Davies, parliamentary under-secretary of state Ben Wallace, secretary of state for defence Baroness Evans of Bowes Park, leader of the House of Lords (minister for investment) Matt Hancock, secretary of state for health and social