The Rabbit and the Medieval East Anglian Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix C: Sites Deferred Due to Not Being Available

Appendix C: sites deferred due to not being available 2020 Reference Previous Nearest Location (Address) Site Area reference Settlement (Hectares) WS526 7.01a Bardwell Land adjacent to Little Moor Hall Farm, 0.29 Bardwell WS527 7.01b Bardwell Land behind The Green, Bardwell 0.32 WS528 WS014 Bardwell Doff's Field, fronting Knox Lane, Bardwell 1.36 WS224 WS041 Barningham Pentland Nursury, Coney Weston Road, 1.67 Barningham WS532 SS11.1 Barrow Land on the corner of Stoney Lane and Bury 0.77 Road, Barrow WS533 SS11.2 Barrow Land south of Stoney Lane, Barrow 0.53 WS024 FHDC/BR/12 Beck Row Land adjacent to Beck Lodge Farm, St Johns 2.75 Stree, Beck Row WS537 BR/13 Beck Row Land west of Aspal Hall Road 1.53 WS288 UCS135 Bury St Edmunds DJ Evans Depot, St Botolphs Lane, Bury St 0.53 Edmunds WS540 UCS156 Bury St Edmunds 40 Hollow Road, Bury St Edmunds 0.69 WS542 SS036 Bury St Edmunds Land at the corner of Symonds Road, Bury 11.74 St Edmunds WS544 SS11.08 Bury St Edmunds Moreton Hall Prep School 8.61 WS545 SS12.9 Bury St Edmunds Land to the west of 38 Horsecroft Road 0.384 WS546 UCS032 Bury St Edmunds St Andrew's Street North, Bury St Edmunds 1.56 WS547 UCS123 Bury St Edmunds Telephone Exchange Car Park, Bury St 0.26 Edmunds WS549 WS007 Bury St Edmunds Land between Horsecroft Road and Sharp 1.17 Road WS550 WS055 Bury St Edmunds West Suffolk Hospital 20.84 WS551 UCS065 Bury St Edmunds Cecil and Larter, Out Risbygate, Bury St 0.25 Edmunds WS557 UCS274 Clare Church Farm, High Street, Clare 0.77 WS303 SP006 Coney Weston Coney Weston campsite, south -

Forest Heath District Council & St Edmundsbury Borough

PUBLIC NOTICE FOREST HEATH DISTRICT COUNCIL & ST EDMUNDSBURY BOROUGH COUNCIL Town and Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (England) Order 2015 Planning (Listed Building and Conservation Areas) ACT 1990 Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (Amendment) Order Advert types: EIA-Applications accompanied by an environmental statement; DP- Not in accordance with the Development Plan; PROW-Affecting a public right of way; M-Major development; LB-Works to a Listed Building; CLB-Within the curtilage of a Listed Building; SLB-Affecting the setting of a Listed Building; LBDC-Listed Building discharge conditions; C-Affecting a Conservation Area; TPO-Affecting trees protected by a Tree Preservation Order; LA- Local Authority Application Notice is given that Forest Heath District Council and St Edmundsbury Borough Council have received the following application(s): PLANNING AND OTHER APPLICATIONS: 1. DC/18/1812/FUL - Planning Application - Steel frame twin span agricultural machinery storage building (following demolition of existing), Home Farm The Street, Ampton (SLB)(C) 2. DC/18/1951/VAR - Planning Application - Variation of Conditions 7, 8 and 9 of DC/14/1667/FUL to enable re-wording of conditions so that they do not need to be implemented in their entirety but require them to be completed within a limited period for the change of use of woodland to Gypsy/Traveller site consisting of five pitches, Land South Of Rougham Hill Rougham Hill, Bury St Edmunds (PROW) 3. DC/18/1995/FUL - Planning Application - Change of use of open recreational space to children’s play area including installation of children’s play area equipment and multi use games area, Land East Of The Street, Ingham (SLB)(TPO) 4. -

WSC Planning Decisions 31/20

PLANNING AND REGULATORY SERVICES DECISIONS WEEK ENDING 31/07/2020 PLEASE NOTE THE DECISIONS LIST RUN FROM MONDAY TO FRIDAY EACH WEEK DC/20/0731/LB Application for Listed Building Consent - (i) Bell Cottage DECISION: Extension of chimney (ii) replacement of Church Road Approve Application windows (iii) removal of cement renders Bardwell DECISION TYPE: pointing and non-traditional infill to timber Bury St Edmunds Delegated frame and replacement with earth and Suffolk ISSUED DATED: lime-based, vapour-permeable materials IP31 1AH 29 Jul 2020 (iv) removal of UPVC and modern painted WARD: Bardwell softwood bargeboards and various window PARISH: Bardwell and door surrounds of modern design with replace with painted softwood (v) painted timber canopy over entrance door and (vi) replace plastic rainwater goods with painted cast iron. As amended by plans received 16th July 2020. APPLICANT: Mr Edward Bartlett DC/20/0740/FUL Planning Application - 1no. dwelling The Old Maltings DECISION: The Street Refuse Application APPLICANT: Mr John Shaw Barton Mills DECISION TYPE: IP28 6AA Delegation Panel AGENT: Richard Denny - M.R. Designs ISSUED DATED: 30 Jul 2020 WARD: Manor PARISH: Barton Mills DC/20/0831/FUL Planning Application - (i) Change of use Bilfri Dairy DECISION: and conversion of barn to dwelling (Class Felsham Road Approve Application C3) (retrospective) (ii) single storey rear Bradfield St George DECISION TYPE: extension (iii) change of use of agricultural IP30 0AD Delegated land to residential curtilage ISSUED DATED: 28 Jul 2020 APPLICANT: Mr. Pickwell and Miss. Milsom WARD: Rougham PARISH: Bradfield St. AGENT: Mr Jonny Rankin - Parker Planning George Services Ltd Planning and Regulatory Services, West Suffolk Council, West Suffolk House, Western Way, Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, IP33 3YU DC/20/0939/TPO TPO 14 (1991) Tree Preservation Order - 1 Walton Way DECISION: (i) 3no. -

Freckenham Neighbourhood Plan Parish Landscape Study: Character and Sensitivity Appraisal

Freckenham Neighbourhood Plan Parish Landscape Study: Character and Sensitivity Appraisal September 2020 Final version Contents: PAGE NO. 1. Landscape and History 3 2. Introduction to the assessment 6 3. Character context 8 4. Methods 10 5. Rural Character Areas 13 Rural character areas map 14 Character area R1 16 Character area R2 19 Character area R3 22 Character area R4 25 Sensitivities: Summary text 28 Sensitivities: Summary map 29 6. Village Character Areas 30 Village character areas 31 Character area VA 33 Character area VB 36 Character area VC 39 Character area VD 42 Character area VE 45 Sensitivities: Summary text 48 Sensitivities: Summary map 49 Report by chartered Landscape Architect Lucy Batchelor-Wylam CMLI Appendix 50 For full appendices of supporting mapping please refer to separate Landscape planning and landscape document architecture services. Tel: 07905 791207 email: [email protected] | Freckenham Landscape Appraisal | Final version September 2020 1. Landscape and history History Mortimer Lane area. 1. Freckenham is a rural parish in the district of West Suffolk (formerly Forest Heath) which 4. The fenland landscape to the west and north was very different. It is a large shallow, sits along the boundary with Cambridgeshire. It lies just to the southwest of Mildenhall, marshy low-lying plain that was subject to repeated flooding by the north sea, and by approximately halfway between Thetford and Cambridge. The parish has the form of water flowing down from the uplands and overflowing the rivers. It was drained in the a thick T or Y shape, and stretches about 3.3 miles from north to south. -

Records of the Sudbury Archdeaconry.

267 RECORDS OF THE SUDBURY ARCHDEACONRY. BY VINCENT B. REDSTONE, H. TERRIERSAND SURVEYS. Constitutions and Canon,Ecclesiastical, issued in 1604, contain an injunction (No. 87), " that a T HEtrue note and terrier of all the glebe lands, &c., . and portions of tithes lying out of their parishes—which belong to any Parsonage, Vicarage, or rural Prebend. be taken by the view of honest men in every parish, by the appointnient of the Bishop—whereof the minister be one—and be laid up in the Bishop's Registry, there to be for a perpetual memory thereof." This injunction does not fix the frequency with which the terriers were to be procured by the Bishop, and, consequently, existing docu- ments of that• character are not to be found for any definite years or periods. It is evident by the existence of early terriers in .the keeping -of the Registrar for the Archdeacon of Sudbury, that such returns were made by churchwardens along .with their presentments• before the year 1604. The terriers at Bury St. Edmund's commence as early as 1576, whilst those in the Bishop's Registry at Norwich, date from 1627.. It is unknown from what circumstances the Archdeacons' Registrars became i)ossessed Of documents which the above mentioned canon dis- tinctly enjoins should be laid up in the Bishop's Registry. In the Exchequer 'there is a terrier of all the glebe lands in England, made about the eleventh year of the reign'of Edward iii. The taxes levied upon the temporal . v VOL. xi. PART 3. 268 RECORDS OF THE possessionSof the Church in every parish throughout the Diocese (see Hail ms. -

Bury St Edmunds Branch

ACCESSIONS 1 OCTOBER 2000 – 31 MARCH 2002 BURY ST EDMUNDS BRANCH OFFICIAL Babergh District Council: minutes 1973-1985; reports 1973-1989 (EH502) LOCAL PUBLIC West Suffolk Advisory Committee on General Commissioners of Income Tax: minutes, correspondence and miscellaneous papers 1960-1973 (IS500) West Suffolk Hospital, Bury St Edmunds: operation book 1902-1930 (ID503) Walnut Tree Hospital, Sudbury: Sudbury Poor Law Institution/Walnut Tree Hospital: notice of illness volume 1929; notice of death volume 1931; bowel book c1930; head check book 1932-1938; head scurf book 1934; inmates’ clothing volume 1932; maternity (laying in ward) report books 1933, 1936; male infirmary report book 1934; female infirmary report books 1934, 1938; registers of patients 1950-1964; patient day registers 1952-1961; admission and discharge book 1953-1955; Road Traffic Act claims registers 1955-1968; cash book 1964-1975; wages books 1982- 1986 (ID502) SCHOOLS see also SOCIETIES AND ORGANISATIONS, PHOTOGRAPHS AND ILLUSTRATIONS, MISCELLANEOUS Rickinghall VCP School: admission register 1924-1994 (ADB540) Risby CEVCP School: reports of head teacher to school managers/governors 1974- 1992 (ADB524) Sudbury Grammar School: magazines 1926-1974 (HD2531) Whatfield VCP School: managers’ minutes 1903-1973 (ADB702) CIVIL PARISH see also MISCELLANEOUS Great Barton: minutes 1956-1994 (EG527) Hopton-cum-Knettishall: minutes 1920-1991; accounts 1930-1975; burial fees accounts 1934-1978 (EG715) Ixworth and Ixworth Thorpe: minutes 1953-1994; accounts 1975-1985; register of public -

Typed By: Apb Computer Name: LTP020

ST EDMUNDSBURY BOROUGH COUNCIL PLANNING AND GROWTH DECISIONS WEEK ENDING 12/03/2018 PLEASE NOTE THE DECISIONS LIST RUN FROM MONDAY TO FRIDAY EACH WEEK DC/17/0724/PMBPA Prior Approval Application under Part 3 of The Barn DECISION: the Town and Country Planning (General Bowbeck Approve Application Permitted Development) (Amendment and Bardwell DECISION TYPE: Consequential Provisions) (England) Order Suffolk Delegated 2015- (i) Change of use of agricultural ISSUED DATED: building to dwellinghouse (Class C3) to 6 Mar 2018 create 1no. dwelling (ii) associated WARD: Bardwell operational development PARISH: Bardwell APPLICANT: Mr J Lumley AGENT: Design And Management. Co. Uk DC/17/2569/LB Application for Listed Building Consent - (i) Forge Cottage DECISION: Replacement of windows and doors (ii) Bowbeck Refuse Application insertion of door and window to west Bardwell DECISION TYPE: elevation and window to south elevation of IP31 1BA Delegation Panel The Forge and Forge Cottage ISSUED DATED: (Retrospective) 9 Mar 2018 WARD: Bardwell APPLICANT: Mr David Tomlinson PARISH: Bardwell AGENT: Mr James Cann -Planning Direct DC/17/2610/HH Householder Planning Application - (i) one Casa Mia DECISION: and a half storey side/rear extension with Water Lane Approve Application Juliet balcony to rear (demolition of Barnham DECISION TYPE: existing flat-roof garage and IP24 2NA Delegated conservatory); (ii) raising of roof to create ISSUED DATED: first floor accommodation with 3 no. front 7 Mar 2018 dormers and (iii) creation of ground floor WARD: Bardwell annexe -

WSC Planning Applications 22/20

LIST 22 29 MAY 2020 Applications Registered between 25 – 29 May 2020 PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED The following applications for Planning Permission, Listed Building, Conservation Area and Advertisement Consent and relating to Tree Preservation Orders and Trees in Conservation Areas have been made to this Council. A copy of the applications and plans accompanying them may be inspected on our website www.westsuffolk.gov.uk. Representations should be made in writing, quoting the application number and emailed to [email protected] to arrive not later than 21 days from the date of this list. Note: Representations on Brownfield Permission in Principle applications and/or associated Technical Details Consent applications must arrive not later than 14 days from the date of this list. Application No. Proposal Location DC/20/0800/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification - (i) The Mill VALID DATE: Mixed species hedge row (H2 on plan) Old Mill Lane 28.05.2020 reduce height to 2 metres above ground Barton Mills level, and reduce sides by 0.75 metres (ii) IP28 6AS EXPIRY DATE: 1no. Weeping Willow (T1 on plan) - overall 09.07.2020 crown reduction by up to 3 metres GRID REF: WARD: Manor APPLICANT: Mr D Scott 572593 273850 PARISH: Barton Mills AGENT: Mr Paul Goldsmith - Green Wood Tree Surgery CASE OFFICER: Falcon Saunders DC/20/0823/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification - Barton Hall VALID DATE: 1no. Beech (T001 on plan) fell The Street 22.05.2020 Barton Mills APPLICANT: Mr & Mrs John Hughes Suffolk EXPIRY DATE: IP28 6AW 03.07.2020 AGENT: Miss Naomi Hull - Temple Property And Construction WARD: Manor CASE OFFICER: Falcon Saunders GRID REF: PARISH: Barton Mills 571827 273953 DC/20/0835/TCA Trees in a Conservation Area Notification - The Dhoon VALID DATE: 1no. -

Coney Weston

1. Parish : Coney Weston Meaning: The King’s enclosure/village 2. Hundred: Blackbourn Deanery: Blackburne (–1972), Ixworth (1972–) Union: Thetford RDC/UDC: (W. Suffolk) Brandon RD (1894–1935), Thingoe RD (1935–1974), St Edmundsbury DC (1974–) Other administrative details: Abolished ecclesiastically to create Barningham with Coney Weston 1802 Blackbourn Petty Sessional Division Thetford County Court District 3. Area: 1,351 acres (1912) 4. Soils: Mixed: a. Slowly permeable seasonally water-logged fine loam over clay b. Deep well drained sand soils, In places very acid. Risk wind erosion 5. Types of farming: 1086 4 acres meadow, wood for 4 pigs, 1 cob, 10 cattle, 12 pigs, 80 sheep, 24 goats 1283 Not recorded 1500–1640 Thirsk: Wood-pasture region, mainly pasture, meadow, engaged in rearing and dairying with some pig keeping, horse breeding and poultry. Crops mainly barley with some wheat, rye, oats, peas, vetches, hops and occasionally hemp. Also has similarities with sheep-corn region where sheep are main fertilising agent, bred for fattening, barley main cash crop. 1818 Marshall: Wide variations of crop and management techniques including summer fallow in preparation for corn and rotation of turnip, barley, clover, wheat on lighter lands 1937 Main crops: Wheat, barley, oats, turnips 1969 Trist: More intensive cereal growing and sugar beet. 1 6. Enclosure: 1777 1,060 acres enclosed under Private Act of Lands 1776 7. Settlement: 1950/1980 Small well spaced development along line of southern boundary with Barningham. Church isolated to west of development. Line of Roman road (Peddars Way) crosses parish from N–S in western sector of parish. -

Situation of Polling Stations West Suffolk

Situation of Polling Stations Blackbourn Electoral division Election date: Thursday 6 May 2021 Hours of Poll: 7am to 10pm Notice is hereby given that: The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Situation of Polling Station Station Ranges of electoral register Number numbers of persons entitled to vote thereat Tithe Barn (Bardwell), Up Street, Bardwell 83 W-BDW-1 to W-BDW-662 Barningham Village Hall, Sandy Lane, Barningham 84 W-BGM-1 to W-BGM-808 Barnham Village Hall, Mill Lane, Barnham 85 W-BHM-1 to W-BHM-471 Barnham Village Hall, Mill Lane, Barnham 85 W-EUS-1 to W-EUS-94 Coney Weston Village Hall, The Street, Coney 86 W-CWE-1 to W-CWE-304 Weston St Peter`s Church (Fakenham Magna), Thetford 87 W-FMA-1 to W-FMA-135 Road, Fakenham Magna, Thetford Hepworth Community Pavilion, Recreation Ground, 88 W-HEP-1 to W-HEP-446 Church Lane Honington and Sapiston Village Hall, Bardwell Road, 89 W-HN-VL-1 to W-HN-VL-270 Sapiston, Bury St Edmunds Honington and Sapiston Village Hall, Bardwell Road, 89 W-SAP-1 to W-SAP-163 Sapiston, Bury St Edmunds Hopton Village Hall, Thelnetham Road, Hopton 90 W-HOP-1 to W-HOP-500 Hopton Village Hall, Thelnetham Road, Hopton 90 W-KNE-1 to W-KNE-19 Ixworth Village Hall, High Street, Ixworth 91 W-IXT-1 to W-IXT-53 Ixworth Village Hall, High Street, Ixworth 91 W-IXW-1 to W-IXW-1674 Market Weston Village Hall, Church Road, Market 92 W-MWE-1 to W-MWE-207 Weston Stanton Community Village Hall, Old Bury Road, 93 W-STN-1 to W-STN-2228 Stanton Thelnetham Village Hall, School Lane, Thelnetham 94 W-THE-1 to W-THE-224 Where contested this poll is taken together with the election of a Police and Crime Commissioner for Suffolk and where applicable and contested, District Council elections, Parish and Town Council elections and Neighbourhood Planning Referendums. -

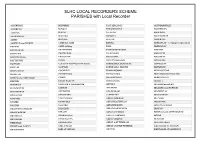

SLHC LOCAL RECORDERS SCHEME PARISHES with Local Recorder

SLHC LOCAL RECORDERS SCHEME PARISHES with Local Recorder ALDEBURGH BRUNDISH EAST BERGHOLT GRUNDISBURGH ALDERTON BUNGAY EDWARDSTONE HACHESTON AMPTON BURGH ELLOUGH HADLEIGH ASHBOCKING BURSTALL ERISWELL HALESWORTH ASHBY BUXHALL EUSTON HARGRAVE ASHFIELD cum THORPE CAMPSEA ASHE EXNING HARKSTEAD - Looking for replacement BACTON CAPEL St Mary EYKE HARLESTON BADINGHAM CHATTISHAM FAKENHAM MAGNA HARTEST BARNHAM CHEDBURGH FALKENHAM HASKETON BARTON MILLS CHEDISTON FELIXSTOWE HAUGHLEY BATTISFORD CLARE FLIXTON (Lowestoft) HAVERHILL BAWDSEY CLAYDON with WHITTON RURAL FORNHAM St. GENEVIEVE HAWKEDON BECCLES CLOPTON FORNHAM St. MARTIN HAWSTEAD BEDINGFIELD COCKFIELD FRAMLINGHAM HEMINGSTONE BELSTEAD CODDENHAM FRECKENHAM HENSTEAD WITH HULVER BENHALL & STERNFIELD COMBS FRESSINGFIELD HERRINGFLEET BENTLEY CONEY WESTON FROSTENDEN HESSETT BLAXHALL COPDOCK & WASHBROOK GIPPING HIGHAM (near BURY) BLUNDESTON CORTON GISLEHAM HIGHAM ( near IPSWICH) BLYTHBURGH COVEHITHE GISLINGHAM HINDERCLAY BOTESDALE CRANSFORD GLEMSFORD HINTLESHAM BOXFORD CRETINGHAM GREAT ASHFIELD HITCHAM BOXTED CROWFIELD GREAT BLAKENHAM HOLBROOK BOYTON CULFORD GREAT BRADLEY HOLTON ST MARY BRADFIELD COMBUST DARSHAM GREAT FINBOROUGH HOPTON BRAISEWORTH DEBACH GREAT GLEMHAM HORHAM with ATHELINGTON BRAMFIELD DENHAM (Eye) GREAT LIVERMERE HOXNE BRAMFORD DENNINGTON GREAT SAXHAM HUNSTON BREDFIELD DRINKSTONE GREAT & LT THURLOW HUNTINGFIELD BROME with OAKLEY EARL SOHAM GREAT & LITTLE WENHAM ILKETSHALL ST ANDREW BROMESWELL EARL STONHAM GROTON ILKETSHALL ST LAWRENCE SLHC LOCAL RECORDERS SCHEME PARISHES with Local -

Bus Services Serving Barton Mills

BUS SERVICES SERVING BARTON MILLS From Monday 2 September 2013 a new timetable was introduced on the Mildenhall to Newmarket bus service operated by Stephensons of Essex. Unfortunately the changes removed all regular daytime buses serving Barton Mills and the only remaining bus services, most of which are operated at school times but are available to the general public, through the village are now: Times Destinations and other information Mornings 0758 to Bury St Edmunds (Bus Station) arriving at 0851 (Mulleys schooldays only service 955 which starts at West Row (0735) then travels via Mildenhall (Bus Station) (0750), Barton Mills (0758), Icklingham, Lackford, Flempton, Hengrave, Fornham and the various Bury schools) 0821 to Mildenhall (MCT Riverside Campus (0829); MCT Bury Road Campus (0835) and Bus Station (0840)) (Stephensons schooldays only service 17 which starts at Cavenham (0755) travelling via Tuddenham (0758), Herringswell (0804), Red Lodge (Warren Road and Hundred Acre Way) and Barton Mills (0821) 0936 to Bury St Edmunds (Bus Station) arriving at 1013 (Mulleys Monday to Saturday (Schooldays and School Holidays) service 356 which starts at Mildenhall (College Heath Road (0925) and Bus Station (0930)) then travelling via Barton Mills (0936), Red Lodge, Herringswell, Tuddenham, Cavenham and Risby) Afternoons 1530 from Bury St Edmunds (Bus Station) to Barton Mills etc (Mulleys schooldays only service 956 picking up at the various Bury schools after leaving the bus station) 1540 from Mildenhall (MCT Bury Road Campus (1540) and MCT Riverside Campus (1548) to Barton Mills (1556) (Stephensons schooldays only service 17 from Mildenhall to Newmarket via Barton Mills, Red Lodge, Herringswell, Tuddenham, Cavenham, Kentford and Moulton.