NIRB Letter to NIRB from Dr. Kunuk and NITV

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

200210 IND 150+Ottawa Press Release Feb

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CELEBRATING INUIT STORYTELLING WITH OTTAWA PREMIERE OF ONE OF CANADA’S TOP 10 FILMS OF 2019 ‘ONE DAY IN THE LIFE OF NOAH PIUGATTUK’ Actor Apayata KotiEr, who plays tHE rolE of NoaH Piugattuk bEing confrontEd by actor Kim Bodnia, playing tHE rolE of Isumataq (Boss). PHoto courtEsy Isuma Distribution. ‘A TOP 10 FILM OF 2019’ - TIFF Monday FEbruary 10th, 2019 -- Coming to Ottawa for it’s Ottawa Public PrEmiErE is OnE Day in tHE LifE of NoaH Piugattuk, the latest film by award-winning, master filmmaker and Order of Canada recipient, Dr. ZacHarias Kunuk. Attending and speaking after the event will be Isuma team member and the film’s assistant director, Lucy Tulugarjuk, and Tessa Kunuk who debuts in the film in the role of Nattuk. The film tells a story of Igloolik elder NoaH Piugattuk who was born in 1900 and passed away in 1996. Noah’s life story is that of Canada’s Inuit in the 20th century – and the film allows the audience to feel and experience for themselves how the movement of Inuit to settlements affected a family, as well as the independence of Inuit people as a nation. Joining the conversation will be Inuit EldEr David SErkoak, educator and speaker on Inuit culture, and former Principal of Nunavut Arctic College. Leading and moderating the discussion will be BernadEttE Dean, Inuit culture and history expert. In the film we meet Noah Piugattuk’s nomadic Inuit band who live and hunt by dogteam, just as his ancestors did when he was born in 1900. -

Iqaluit's Malaya Qaunirq Chapman Stars in Big New Feature Lm

5/1/2020 Iqaluit’s Malaya Qaunirq Chapman stars in big new feature film | Nunatsiaq News IQALUIT KUUJJUAQ 0° -9° cloudy partly cloudy FRIDAY, 1 MAY, 2020 JOBS TENDERS NOTICES ADVERTISE ABOUT US CONTACT E-EDITION NEWS FEATURES EDITORIAL LETTERS OPINION TAISSUMANI ARCHIVES NEWS 25 JULY 2019 – 3:30 PM EDT Iqaluit’s Malaya Qaunirq Chapman stars in big new feature lm Arnait Video’s Restless River set in the Kuujjuaq of the 1940s, 50s https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/iqaluits-malaya-qauniq-chapman-stars-in-big-new-feature-film/ 1/8 5/1/2020 Iqaluit’s Malaya Qaunirq Chapman stars in big new feature film | Nunatsiaq News Iqaluit’s Malaya Qaunirq Chapman stars in Restless River, a new feature lm from Arnait Video Productions that will get a theatrical release this fall. By Nunatsiaq News A big new feature lm set in Kuujjuaq and starring Iqaluit’s Malaya Qaunirq Chapman is set for release in theatres this fall, the lm’s producers announced this week. Set in Fort Chimo, as Kuujjuaq was known in the 1940s and 1950s, Restless River is inspired by a short novel, titled La Rivière Sans Repos in French and Windower in English, that the renowned francophone writer Gabrielle Roy published in 1970. https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/iqaluits-malaya-qauniq-chapman-stars-in-big-new-feature-film/ 2/8 5/1/2020 Iqaluit’s Malaya Qaunirq Chapman stars in big new feature film | Nunatsiaq News The lm’s central narrative is built around the character of a young Inuk woman named Elsa, who, shortly after the end of World War II, is raped by an American soldier stationed at the Fort Chimo air force base. -

Uvagut TV Fulfils a Long-Cherished Dream, NITV Chairperson Says

https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/uvagut-tv-fulfils-a-long-cherished-dream-nitv-chairperson-says/ 15 January 2021 – 5:12 pm EST Uvagut TV fulfils a long-cherished dream, NITV chairperson says New Inuit language channel will include six hours of IBC programming each day Rita Claire Mike-Murphy in a scene from Anana’s Tent, a children’s program from Taqqut Productions that will be available on Uvagut TV. (Photo courtesy of Isuma) By Jim Bell When the groundbreaking Uvagut TV channel launches Monday, a long-cherished dream will have been realized, the chairperson and executive director of Nunavut Independent Television, Lucy Tulugarjuk, told Nunatsiaq News this week. “We’ve been hoping for a long time to have Inuit television, or Uvagut TV, TV in Inuktitut,” Tulugarjuk said. 1 https://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/uvagut-tv-fulfils-a-long-cherished-dream-nitv-chairperson-says/ The chairperson and executive director of Nunavut Independent Television, Lucy Tulugarjuk. (Photo courtesy of Isuma) NITV and a related Igloolik-based company, Isuma TV, will build the channel on a vast database of Inuit language video material they’ve been gathering for nearly 20 years and offering to the public through an on-demand online streaming site. Now, they’ll be able to broadcast the same material on their own channel, to be carried by Arctic Co-operatives Ltd. and Shaw Direct. Another group that’s happy about the new channel is the Inuit Broadcasting Corp., which will supply programming to Uvagut TV for six hours a day. “I believe that Inuit deserve to see these programs,” Manitok Thompson, the CEO of IBC, said in a statement. -

Mother Tongue Film Festival

2016–2020 Mother Tongue Film Festival Five-Year Report RECOVERING VOICES 1 2 3 Introduction 5 By the Numbers 7 2016 Festival 15 2017 Festival 25 2018 Festival 35 2019 Festival 53 2020 Festival 67 Looking Ahead 69 Appendices Table of Contents View of the audience at the Last Whispers screening, Terrace Theater, Kennedy Center. Photo courtesy of Lena Herzog 3 4 The Mother Tongue Film Festival is a core to the Festival’s success; over chance to meet with guest artists and collaborative venture at the Smithso- time, our partnerships have grown, directors in informal sessions. We nian and a public program of Recov- involving more Smithsonian units and have opened the festival with drum ering Voices, a pan-institutional pro- various consular and academic part- and song and presented live cultural gram that partners with communities ners. When launched, it was the only performances as part of our festival around the world to revitalize and festival of its kind, and it has since events. sustain endangered languages and formed part of a small group of local knowledge. The Recovering Voices and international festivals dedicated We developed a dedicated, bilingual partners are the National Museum of to films in Indigenous languages. (English and Spanish) website for Natural History, the National Museum the festival in 2019, where we stream of the American Indian, and the Cen- Over its five editions, the festival has several works in full after the festival. ter for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. grown, embracing a wide range of And, given the changing reality of our Through interdisciplinary research, audiovisual genres and experiences, world, we are exploring how to pres- community collaboration, and pub- drawing audiences to enjoy screen- ent the festival in a hybrid live/on- lic outreach, we strive to develop ef- ings often at capacity at various ven- line model, or completely virtually, in fective responses to language and ues around Washington, DC. -

Reference Guide This List Is for Your Reference Only

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA ACT OF THE HEART BLACKBIRD 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / 2012 / Director-Writer: Jason Buxton / 103 min / English / PG English / 14A A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a Sean (Connor Jessup), a socially isolated and bullied teenage charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest conductor goth, is falsely accused of plotting a school shooting and in her church choir. Starring Geneviève Bujold and Donald struggles against a justice system that is stacked against him. Sutherland. BLACK COP ADORATION ADORATION 2017 / Director-Writer: Cory Bowles / 91 min / English / 14A 2008 / Director-Writer: Atom Egoyan / 100 min / English / 14A A black police officer is pushed to the edge, taking his For his French assignment, a high school student weaves frustrations out on the privileged community he’s sworn to his family history into a news story involving terrorism and protect. The film won 10 awards at film festivals around the invites an Internet audience in on the resulting controversy. world, and the John Dunning Discovery Award at the CSAs. With Scott Speedman, Arsinée Khanjian and Rachel Blanchard. CAST NO SHADOW 2014 / Director: Christian Sparkes / Writer: Joel Thomas ANGELIQUE’S ISLE Hynes / 85 min / English / PG 2018 / Directors: Michelle Derosier (Anishinaabe), Marie- In rural Newfoundland, 13-year-old Jude Traynor (Percy BEEBA BOYS Hélène Cousineau / Writer: James R. -

Canada Council for the Arts Funding to Artists and Arts Organizations in Nunavut, 2006-07

Canada Council for the Arts Funding to artists and arts organizations in Nunavut, 2006-07 Research Unit – Canada Council for the Arts Table of Contents Table of Contents 1.0 Overview of Canada Council funding to Nunavut in 2006-07 ................................................................. 1 2.0 Statistical highlights about the arts in Nunavut ........................................................................................... 2 3.0 Highlights of Canada Council grants to Nunavut artists and arts organizations .............................. 3 4.0 Overall arts and culture funding in Nunavut by all three levels of government .............................. 6 5.0 Detailed tables of Canada Council funding to Nunavut ............................................................................ 9 List of Tables Table 1: Government expenditures on culture, to Nunavut, 2003-04 ........................................................... 7 Table 2: Government expenditures on culture, to all provinces and territories, 2003-04 .....................7 Table 3: Government expenditures on culture $ per capita by province and territory, 2003-04 ........ 8 Table 4: Canada Council grants to Nunavut and Canada Council total grants, 1999-00 to 2006-07 ........................................................................................................................ 9 Table 5: Canada Council grants to Nunavut by discipline, 2006-07 ............................................................ 10 Table 6: Grant applications to the Canada Council -

Films. Farther. | 877.963.Film

FILMS. FARTHER. | 877.963.FILM | WWW.WIFILMFEST.ORG Production & Health Insurance • Industry Discounts • Essential Resources • YOU’RE AN Regional Salons • INDEPENDENT FILMMAKER. Online Resources • OUR COMPANY IS CALLED INDEPENDENT. JOIN AIVF AIVF: promoting the diversity and democracy of NEED WE SAY MORE? ideas & images 304 Hudson St. 6th fl. New York, NY 70013 (212) 807-1400; fax: (212) 463-85419 [email protected]: www.aivf.org FILMMAKER FRIENDLY. EDITING > AUDIO > MUSIC Regent Entertainment and Steve Jarchow are pleased to 777 NORTH JEFFERSON STREET support the MILWAUKEE,WI 53202 Wisconsin Film Festival. TEL: 414.347.1100 FAX: 414.347.1010 E-MAIL: [email protected] WEB: www.i777.com 2 WISCONSIN FILM FESTIVAL • APRIL 4-7, 2002 • MADISON • WWW.WIFILMFEST.ORG • 877.963.FILM overnightStay at Madison ’s premiere hotel featuring a fitness center,game room, indoor pool, whirlpool,steam room, in-room Nintendo, restaurants and bar, and you ’ll also find yourself sensationin the heart of downtown with the of State Street shops,galleries,theater, campus and lakes all within walking distance. 1 W.Dayton St.•Madison,WI • 608-257-6000 •800-356-8293 TTY:608-257-2980 •www.concoursehotel.com modern classics The Film Festival Coffeehouse Connection Convenient In the heart of downtown and close to campus. Lively Sip a latte, a chai, or a coffee. Sit back and BS with friends. Easy Hours Open Early - Close Late. WORKBENCH 544 State Street FURNITURE EXTENDED FILM FESTIVAL HOURS: Madison Mon-Thur 7:30am-11pm, Fri 7:30am - 1am, Sat. 9am-1am, Sun 10am-11pm 7610 Mineral Point Road, West of High Point Center 608-833-0111 SPECIAL EVENT: Enjoy coffee and informal discussions with featured 10% off any single item filmmakers from the Wisconsin Film Festival. -

One Day in the Life-Preliminary Notes-05Jul19

Kingulliit Productions and Isuma Productions present ᓄᐊ ᐱᐅᒑᑦᑑᑉ ᐅᓪᓗᕆᓚᐅᖅᑕᖓ ONE DAY IN THE LIFE OF NOAH PIUGATTUK *** PRELIMINARY PRESS NOTES – AS OF JULY 5, 2019 *** FEATURING Apayata Kotierk as Noah Piugattuk Kim Bodnia Isumataq (Boss) Benjamin Kunuk Evaluarjuk (Ningiuq) Mark Taqqaugaq Amaaq Neeve Uttak Tatigat Tessa Kunuk Nattuk Zacharias Kunuk Writer / Producer / Director Norman Cohn Writer / Director of Photography / Editor Jonathan Frantz Producer / Co-director of Photography / Co-editor Lucy Tulugarjuk First Assistant Director Susan Avingaq Production Designer Carol Kunnuk Production Supervisor Noah Piugattuk Music Running Time: 113 minutes Languages: Inuktitut, English DCP – Dolby 5.1 Shot in 4K Digital Kapuivik, north Baffin Island, 1961. Noah Piugattuk’s nomadic Inuit band live and hunt by dogteam, just as his ancestors did when he was born in 1900. When the white man known as Boss arrives in camp, what appears as a chance meeting soon opens up the prospect of momentous change. In today’s contentious global media environment, when millions of people have been driven from their homes worldwide, Isuma media art in the UN Year of Indigenous Languages looks at the forced relocation of families from an Inuit point of view. Our name Isuma means ‘to think,’ a state of thoughtfulness, intelligence or an idea. As this film illuminates Canada’s relocation of Inuit in the 1950s and 60s, we seek to reclaim our history and imagine a different future. DIRECTOR’S VISION – ZACHARIAS KUNUK Igloolik elder Noah Piugattuk was born in 1900 and passed away in 1996. His life story is that of Canada’s Inuit in the 20th century – that of my parents’ generation and my own. -

Annual General Report 2019-2020

ANNUAL GENERAL REPORT 2019-2020 P.O. Box 2398, Unit 107-8 Storey, Iqaluit, Nunavut X0A 0H0 p 867.979.3012 l e [email protected] l w www.nunavutfilm.ca Nunavut Film Development Corporation 1 Annual General Report 2019-2020 2019-2020 ECONOMIC IMPACT OF NUNAVUT FILM DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION FUNDING* *based on the Nunavut Spend Incentive 100% OF FILMS 267 INUIT 7 COMMUNITY IN INUKTUT EMPLOYED LOCATIONS tion roduc DC P Tota NF nding Nuna l Fu ted: vut Sp ntribu on Lo end Co cation 8 : 775.6 $4 775, ,323,5 $ 74.33 $1 NFDC funding generates $5.57 of spend in NU ction rodu DP: otal P to G T ution 9 ntrib 56.6 Co 07,3 $9,4 $1 NFDC funding contributes $12.13 to GDP 12 INUIT TRAINEE POSITIONS CREATED 8 COMMUNITIES VISITED BY NFDC 40 ATTENDED INDUSTRY TRAINING WORKSHOPS OF PRODUCTIONS RECEIVED FUNDING 87% FROM THE INUKTUT LANGUAGE INCENTIVE FUND** **based on SF, IVF, NSI The Nunavut Film Development Corporation (NFDC) provides training and funding through seven funding programs for the production and marketing of screen-based media. NFDC also provides a service through the operation of the Nunavut Film Commission. NFDC’s 2019-2020 Operations and Management core budget is $326,000 and its Film, Television and Digital Media Funding budget is $1,235,000. Mandate The Nunavut Film Development Corporation (NFDC) is mandated by the Government of Nunavut to increase economic opportunities for Nunavummiut in the screen-based industry, and to promote Nunavut as a world-class circumpolar production location. -

Indigenous Film Programme

INDIGENOUS FILM PROGRAMME "Please don't stop doing this. It's inclusive and it continues to strengthen the idea that these kids count, these communities count, and that people all over Canada are ready to listen to them." — Cathy Elliott, Program Director, DAREarts REEL CANADA WHO WE ARE Uniting our nation through film REEL CANADA is a charitable organization whose mission is to introduce new audiences to the power and diversity of Canadian film. Our travelling film festival has held nearly 1,200 screenings and reached more than 600,000 students — and it just keeps growing. WHAT WE DO WHY WE DO IT Our work is delivered via three core programmes: We believe — and our audiences confirm — that seeing oneself on film can be a profound and Our Films in Our Schools: For over 11 years, transformative experience. Canadian film depicts we have helped teachers and students across the unique experience of Canadians in a way Canada organize over one thousand screenings of that the commercial marketplace generally does Canadian film, providing educational resources to not provide. For young people and newcomers facilitate classroom integration. especially, who are actively engaged in understanding their place in the world, Canadian Welcome to Canada: We introduce new Canadians movies offer a way to see themselves and consider to Canadian film and culture through festival the qualities and values that define us. events designed specifically for English-language learners of all ages. Movies are a mirror. Canadian movies reflect the Canadian experience. Great Canadian movies tell National Canadian Film Day (NCFD): An annual us who we are as individuals and have the power one-day event where Canadians from coast to to help bring us together as a country. -

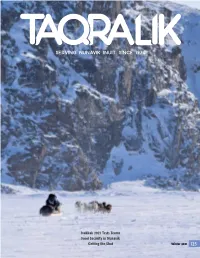

Issue 125-2021

SERVING NUNAVIK INUIT SINCE 1974 Ivakkak 2021 Tests Teams Food Security in Nunavik Getting the Shot Winter 2021 125 Makivik Corporation Makivik is the ethnic organization mandated to represent and promote the interests of Nunavik. Its membership is composed of the Inuit beneficiaries of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA). Makivik’s responsibility is to ensure the proper implementation of the political, social, and cultural benefits of the Agreement, and to manage and invest the monetary compensation so as to enable the Inuit to become an integral part of the Northern economy. Taqralik Taqralik is published by Makivik Corporation and distributed free of charge to Inuit beneficiaries of the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement. The opinions expressed herein are not necessarily those of Makivik Corporation or its Executive. We welcome letters to the editor and submissions of articles, artwork or photographs. Email [email protected] or call 1-800-361-7052 for submissions or for more information. Makivik Corporation Executives Pita Aatami, President Maggie Emudluk, Vice President, Economic Development Adamie Delisle Alaku, Vice President, Environment, Wildlife and Research George Berthe, Treasurer Rita Novalinga, Corporate Secretary We wish to express our sincere thanks to all Makivik staff, as well as to all others who provided assistance and materials to make the production of this magazine possible. Director of Communications Carson Tagoona Editor Miriam Dewar Translation/Proofreading Minnie Amidlak Sarah Aloupa Eva Aloupa-Pilurtuut Alasie Kenuajuak Hickey CONTENTS Published by Makivik Corporation P.O. Box 179, Kuujjuaq (QC) J0M 1C0 Canada Telephone: 819-964-2925 *Contest participation in this magazine is limited to Inuit beneficiaries of the JBNQA. -

About Isuma & Artist Bios

ABOUT ISUMA In 1985, the Inuktitut-language video, From Inuk Point of View, broke the race-barrier at Canada Council for the Arts when Zacharias Kunuk became the first Inuit or Indigenous applicant ruled eligible to apply for a professional artist’s grant. Kunuk was the video’s director; Norman Cohn was cameraman; Paul Apak was editor; and elder Pauloosie Qulitalik told the story, and by 1990, the four partners formed Igloolik Isuma Productions Inc. to produce independent video art from an Inuit point of view. Early Isuma videos featuring actors recreating Inuit life in the 1930s and 1940s were shown to Inuit at home and in museums and galleries around the world. Over the next ten years Isuma artists helped establish an Inuit media arts centre, NITV; a youth media and circus group, Artcirq; and a women's video collective, Arnait Video Productions. In 2001, Isuma’s first feature-length drama, Atanarjuat The Fast Runner, won the Camera d’or at the Cannes Film Festival; in 2002, both Atanarjuat and Nunavut (Our Land), a 13-part TV series, were shown at Documenta 11 in Kassel, Germany. Isuma’s second feature, The Journals of Knud Rasmussen, opened the 2006 Toronto International Film Festival, and its third feature, Before Tomorrow, written and directed by Igloolik’s Arnait Video Productions women’s collective, was screened in World Cinema Competition at the 2009 Sundance Film Festival. In 2008, Isuma launched IsumaTV, the world’s first website for Indigenous media art, now showing over 6,000 films and videos in 84 languages. In 2012, Isuma produced Digital Indigenous Democracy, an internet network to inform and consult Inuit in low-bandwidth communities facing development of the Baffinland Iron Mine and other resource projects; and in 2014, produced My Father’s Land, a non-fiction feature about what took place during this intervention.