Pg1653 Hidalgo 10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

33581 THE WORLD BANK GROUP 2004 A THE WORLDBANKGROUP Headquarters 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. NNUAL Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Telephone: (202) 473-1000 Facsimile: (202) 477-6391 Website: www.worldbank.org M EETINGS Cable Address World Bank: INTBAFRAD IFC: CORINTFIN THE WORLD BANK GROUP IDA: INDEVAS OF MIGA: MIGAVEST THE B SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS OARDS Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized OF 2004 ANNUAL MEETINGS G OVERNORS OF THE OARDS OF OVERNORS B G Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Summary Proceedings Washington D.C. October 3, 2004 Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized 3645_p00i-viii_FrontMatter.pdf 8/24/05 9:30 AM Page i THE WORLD BANK GROUP 2004 ANNUAL MEETINGS OF THE BOARDS OF GOVERNORS SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS WASHINGTON D.C. OCTOBER 3, 2004 3645_p00i-viii_FrontMatter.pdf 8/24/05 9:30 AM Page ii 3645_p00i-viii_FrontMatter.pdf 8/24/05 9:30 AM Page iii INTRODUCTORY NOTE The 2004 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group, which consists of the International Bank for Reconstruc- tion and Development (IBRD), International Finance Corporation (IFC), International Development Association (IDA), Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) and International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), held jointly with that of the International Monetary Fund, took place on October 3, 2004 in Washington D.C. The Honorable Lim Hng Kiang, Governor of the Bank and the Fund for Singapore, served as the Chairman. The Summary Proceedings record, in alphabetical order by member countries, the texts of statements by Governors, the reports and resolu- tions adopted by the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group. -

Department for International Development Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20

Department for International Development Annual Report and Accounts 2019-20 HC 517 Department for International Development Annual Report and Accounts 2019‑20 Annual Report presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 1 of the International Development (Reporting and Transparency) Act 2006 Accounts presented to the House of Commons pursuant to Section 6(4) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 Accounts presented to the House of Lords by Command of Her Majesty Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 14 July 2020 HC 517 1 © Crown copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open‑government‑licence/ version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official‑documents Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] This is part of a series of departmental publications which, along with the Main Estimates 2020‑21 and the document Public Expenditure: Statistical Analyses 2019, present the government’s outturn for 2019‑20 and planned expenditure for 2020‑21 ISBN 978‑1‑5286‑1866‑3 CCS0320348248 07/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Contents Section 1: Performance Report 5 Overview 5 Foreword -

Annual Report and Resource Accounts 09: Volume 2

Better results for poor people Annual Report and Resource Accounts 2008–09: Volume 2 How to Contact us DFID’s Public Enquiry Point is dedicated to answering your questions Call: 0845 300 4100 (UK Local call rate) +44 1355 84 3132 (from outside the UK) Write: Public Enquiry Point DFID Abercrombie House Eaglesham Road East Kilbride Glasgow G75 8EA Email: enquiry@dfid.gov.uk Website: www.dfid,gov.uk Department for International Development Annual Report and Resource Accounts 2008 – 09 Volume II of II Departmental Resource Accounts and Annexes Resource Accounts presented to the House of Commons pursuant to Section 6(4) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000. Departmental Report presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for International Development pursuant to Section 1 of the International Development (Reporting and Transparency) Act 2006. Report and Accounts presented to the House of Lords by Command of Her Majesty. Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 16th July 2009. London: The Stationery Office HC 867-II Not to be sold separately £42.55 Cover photography: IVORY COAST Abidjan Cocoa beans being loaded onto a cargo ship at the port.The country is among the world’s largest producers of cocoa. Photographer © Sven Torfinn/Panos Picture Cover Photography: All photographs throughout this report are credited to DFID unless otherwise stated. This is part of a series of departmental reports which, along with the Main Estimates 2009-10, the document Public Expenditure: Statistical Analyses 2009, and the Supply Estimates 2009-10: Supplementary Budgetary Information, present the Government’s outturn and planned expenditure for 2009-10 and 2010-11. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2013–14

Department for International Development Annual Report and Accounts 2013–14 HC 11 Department for International Development Annual Report and Accounts 2013–14 Annual Repor t presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 1 of the International Development (Repor ting and Transparency) Act 2006 Accounts presented to the House of Commons pursuant to Section 6(4) of the Government Resources and Accounts Act 2000 Accounts presented to the House of Lords by Command of Her Majesty Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 15 July 2014 HC 11 © Crown copyright 2014 You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v.2. To view this licence visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ doc/open-government-licence/version/2/ or email [email protected] Where third par ty material has been identified, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/government/publications Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at enquiry@dfid.gov.uk Print ISBN 9781474106634 Web ISBN 9781474106641 Printed in the UK by The Williams Lea Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office ID SGD004702 06/14 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum Contents Headline results 4 Foreword by the Secretary of State 5 Lead Non-Executive Director’s introduction to the Annual Report 8 Chapter 1: DFID overview, priorities and expenditure 9 Chapter 2: DFID results 19 Chapter -

The United Kingdom's 2001-2003 Preparation for the Invasion of Iraq

1 Between Dream and Deed: The United Kingdom’s 2001-2003 Preparation for the Invasion of Iraq by KAROLIEN EMMA MICHELLE KEARY Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS at DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL POLITICS ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY 2017 2 Between Dream and Deed: The United Kingdom’s 2001-2003 Preparation for the Invasion of Iraq by KAROLIEN EMMA MICHELLE KEARY Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS at DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL POLITICS ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY 2017 3 To my grandmothers, who should have had a chance to study geography and languages. 4 Declarations This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. I give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for interlibrary loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. The word count of the thesis is 90,397 words. The views expressed in this work are the author’s own and do not reflect the official position of the Federal Public Service of Foreign Affairs or the Belgian government. 5 Acknowledgements When four years ago I pleaded with the department to get Hidemi as a new supervisor, I knew working with him would be an intellectual delight and suspected it would change the way I understood the world. -

Doing Business in Indonesia • Bribery and Corruption 98 • Intellectual Property 99 • Payment Risks in Indonesia

Doing Business in Indonesia k Jakarta Skyline u . o c . e d i u G s s e n i s u B g n i o D . a i s e n o d n I . w w w www. Indonesia .Doing Business Guide .co.uk Visit the Website and download the free Mobile App SUPPORTED BY: CONTENTS 7 Indonesia overview 9 Welcome from Lesley Batchelor OBE, FIEx (Grad) – Director General, Institute of Export & International Trade 11 Foreword from Moazzam Malik, British Ambassador to Indonesia, ASEAN and Timor-Leste 13 Welcome from Mr Richard Graham MP, Prime Minister’s Trade Envoy to Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and the ASEAN Economic Community 15 Introduction from Joel Derbyshire, Director of International Trade and Investment at the British Embassy Jakarta, Department for International Trade 16 Foreword from Chris Wren, CEO, BritCham Indonesia 19 Introduction from Ross Hunter, Executive Director, UK-ASEAN Business Council www. China .Doing Business Guide .co.uk 3 41 27 Why Indonesia? 28 • Summary Help available 29 • Geography • General overview 30 • Government overview for you 31 • Economic overview 41 Help available for you 43 • Overview • Support from the Department for International Trade (DIT) 47 • Support from the Institute of Export & International Trade 49 • Support from the UK-ASEAN Business Council 51 Getting here and advice about your stay 52 • Entry requirements for Indonesia 53 • Travel advice • Local laws 54 • Safety and security 56 • Local travel 57 • Political situation 58 • Natural disasters 59 • Health 60 • FCO travel advice 63 Sector-specific opportunities 64 • Research -

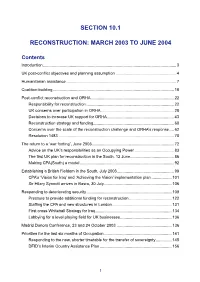

Section 10.1 Reconstruction

SECTION 10.1 RECONSTRUCTION: MARCH 2003 TO JUNE 2004 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 UK post-conflict objectives and planning assumption ...................................................... 4 Humanitarian assistance .................................................................................................. 7 Coalition-building ............................................................................................................ 18 Post-conflict reconstruction and ORHA .......................................................................... 22 Responsibility for reconstruction .............................................................................. 22 UK concerns over participation in ORHA ................................................................. 28 Decisions to increase UK support for ORHA ............................................................ 43 Reconstruction strategy and funding ........................................................................ 60 Concerns over the scale of the reconstruction challenge and ORHA’s response .... 62 Resolution 1483 ....................................................................................................... 70 The return to a ‘war footing’, June 2003 ......................................................................... 72 Advice on the UK’s responsibilities as an Occupying Power ................................... 83 The first UK plan -

ASEAN@50 Business Forum

ASEAN@50 Business Forum The UK & ASEAN: New Opportunities. New Futures 11 October 2017 Role Players Session One: 3pm – 4.15pm. Fifty Years Young: What’s next for the future of ASEAN? What can we look forward to with the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) Blueprint 2025? Scene Setting by: Richard Graham MP - Prime Minister’s Trade Envoy to Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and the AEC. Followed by panel discussion with: • Richard Graham MP - Prime Minister’s Trade Envoy to Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and the AEC. • H.E. Moazzam Malik, Ambassador of the UK to ASEAN and Indonesia. • Dr. Douglas Lippoldt, Chief Trade Economist, HSBC Global Research • Dr. Jürgen Haacke, Director, The Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia. Centre, London School of Economics and Political Science. Moderated by Dr. Linda Yueh, Fellow in Economics, St Edmund Hall, Oxford University. Richard Graham has been MP for Gloucester since 2010. He was Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) to two Ministers of State at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and is now the Prime Minister’s Trade Envoy to the ASEAN Economic Community, Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia. He is Chairman of the All Party Parliamentary Group on China, Indonesia and Marine Energy and Tidal Lagoons and is a Director of the Great Britain China Centre. Richard was previously an airline manager, a diplomat and an investment manager. He has worked in ten countries, speaks eight languages and is a charity trustee. UKABC reserves the right to alter the content/timing and is not responsible for cancellations due to unforeseen circumstances. -

The Good News from Pakistan How a Revolutionary New Approach to Education Reform in Punjab Shows the Way Forward for Pakistan and Development Aid Everywhere

The good news from Pakistan How a revolutionary new approach to education reform in Punjab shows the way forward for Pakistan and development aid everywhere Sir Michael Barber March 2013 The good news from Pakistan How a revolutionary new approach to education reform in Punjab shows the way forward for Pakistan and development aid everywhere Sir Michael Barber March 2013 Reform Reform is an independent, non-party think tank whose mission is to set out a better way to deliver public services and economic prosperity. Reform is a registered charity, the Reform Research Trust, charity no. 1103739. This publication is the property of the Reform Research Trust. We believe that by reforming the public sector, increasing investment and extending choice, high quality services can be made available for everyone. Our vision is of a Britain with 21st Century healthcare, high standards in schools, a modern and efficient transport system, safe streets, and a free, dynamic and competitive economy. 1 The author Sir Michael Barber is the Department for International Development’s (DfID) (unpaid) Special Representative on Education in Pakistan and Chief Education Advisor at Pearson. He is one of the world’s leading education reformers, and from 2001 to 2005 was Chief Advisor on Delivery to Prime Minister Tony Blair. From 2005 to 2011 at McKinsey, he founded its Global Education Practice and was a leader of its public sector work. Sir Michael is the author or co-author of a number of influential reports, including How the World’s Best Performing School Systems Come Out on Top, How the World’s Most Improved School Systems Keep Getting Better and Oceans of Innovation. -

World Bank Document

THE WORLD BANK GROUP 2005 A THE WORLDBANKGROUP Headquarters 1818 H Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20433, U.S.A. NNUAL Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Telephone: (202) 473-1000 Facsimile: (202) 477-6391 Website: www.worldbank.org M EETINGS THE WORLD BANK GROUP OF THE B SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS OARDS Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized OF 2005 ANNUAL MEETINGS G OVERNORS OF THE OARDS OF OVERNORS B G Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized Summary Proceedings Washington D.C. September 24–25, 2005 Public Disclosure AuthorizedPublic Disclosure Authorized 3807-CH00_FM_pi-viii.pdf 3/24/06 7:22 AM Page i THE WORLD BANK GROUP 2005 ANNUAL MEETINGS OF THE BOARDS OF GOVERNORS SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS WASHINGTON D.C. SEPTEMBER 24–25, 2005 3807-CH00_FM_pi-viii.pdf 3/24/06 7:22 AM Page ii 3807-CH00_FM_pi-viii.pdf 3/24/06 7:22 AM Page iii INTRODUCTORY NOTE The 2005 Annual Meetings of the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group, which consists of the International Bank for Reconstruc- tion and Development (IBRD), International Finance Corporation (IFC), International Development Association (IDA), Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) and International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), held jointly with that of the International Monetary Fund, took place on September 24–25, 2005 in Washington, D.C. The Honorable Andre-Philippe Futa, Gover- nor of the Bank and the Fund for the Democratic Republic of the Congo, served as the Chairman. The Summary Proceedings record, in alphabetical order by member countries, the texts of statements by Governors, the resolutions and reports adopted by the Boards of Governors of the World Bank Group. -

Anti-Corruption Strategy and the Illegal Wildlife Trade 3

DEBATE PACK Number CDP-0048 | 26 February 2018 Compiled by: Nigel Walker Anti-corruption strategy Antonia Garraway Julie Gill and the illegal wildlife Subject specialists: Elena Ares trade Jon Lunn Contents Westminster Hall 1. Background 2 2. Press Articles 4 Wednesday 28 February 2018 3. Press releases 6 4. PQs 18 2:30 - 4:00 pm 5. Other Parliamentary material 32 Debate initiated by Dr Rupa Huq MP 5.1 Debates 32 5.2 Statements 32 5.3 Early Day Motions 38 6. Further reading 39 The House of Commons Library prepares a briefing in hard copy and/or online for most non-legislative debates in the Chamber and Westminster Hall other than half-hour debates. Debate Packs are produced quickly after the announcement of parliamentary business. They are intended to provide a summary or overview of the issue being debated and identify relevant briefings and useful documents, including press and parliamentary material. More detailed briefing can be prepared for Members on request to the Library. www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Number CDP-0048, 26 February 2018 1. Background On 11 December 2017, the UK Government issued its first cross- government anti-corruption strategy to guide its actions through to 2022. On page 16 it says: “Criminal networks rely on corruption to facilitate illegal migration, modern slavery, drug trafficking and the illegal trade in wildlife.” On page 62 it provided further detail: The illegal wildlife trade (IWT), worth up to £17 billion a year, is the fourth most lucrative transnational crime after human trafficking, drugs and arms. -

Making Governance Work for the Poor

eliminating world poverty making governance work for the poor A White Paper on International Development Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for International Development by Command of Her Majesty July 2006 © Crown Copyright 2006 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and departmental logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing that it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Any enquiries relating to the copyright in this document should be addressed to The Licensing Division, HMSO, St Clements House, 2-16 Colegate, Norwich, NR3 1BQ. Fax: 01603 723000 or e-mail: [email protected] Cm 6876 | £24 contents Foreword by the Prime Minister ii Chapter 6 Investing in people 72 From commitments to results 73 Preface: the challenge for our generation iii Getting children into school 76 This White Paper xi Improving health 78 Providing clean water and sanitation 82 Protecting the very poorest 84 Delivering our promises Chapter 1 Delivering the promises of 2005 2 The case for development 3 Working internationally to tackle climate change Poverty is falling, but progress is uneven 6 Making progress against the 2005 commitments 9 Chapter 7 Managing climate change 90 The climate is changing 91 Climate change matters for development 92 Working for an international solution 93 Building states that work for poor people Making the shift to cleaner energy 96 Chapter