ACARP C22029 Managing Cumulative Impacts in Mixed-Industry Regions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Region Region

THE MACKAY REGION Visitor Guide 2020 mackayregion.com VISITOR INFORMATION CENTRES Mackay Region Visitor Information Centre CONTENTS Sarina Field of Dreams, Bruce Highway, Sarina P: 07 4837 1228 EXPERIENCES E: [email protected] Open: 9am – 5pm, 7 days (May to October) Wildlife Encounters ...........................................................................................4–5 9am – 5pm Monday to Friday (November to April) Nature Reserved ..................................................................................................6–7 9am – 3pm Saturday Hooked on Mackay ...........................................................................................8–9 9am – 1pm Sunday Family Fun ..............................................................................................................10–11 Melba House Visitor Information Centre Local Flavours & Culture ............................................................................12–13 Melba House, Eungella Road, Marian P: 07 4954 4299 LOCATIONS E: [email protected] Cape Hillsborough & Hibiscus Coast ...............................................14–15 Open: 9am – 3pm, 7 days Eungella & Pioneer Valley .........................................................................16–17 Mackay Visitor Information Centre Mackay City & Marina .................................................................................. 18–19 320 Nebo Road, Mackay (pre-Feb 2020) Northern Beaches .........................................................................................20–21 -

Moranbah Public Hearing—Inquiry Into the Mineral Resources (Galilee Basin) Amendment Bill 2018

STATE DEVELOPMENT, NATURAL RESOURCES AND AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE Members present: Mr CG Whiting MP (Chair) Mr JE Madden MP Mr BA Mickelberg MP Mr PT Weir MP Member in attendance: Mr MC Berkman MP Staff present: Dr J Dewar (Committee Secretary) PUBLIC HEARING—INQUIRY INTO THE MINERAL RESOURCES (GALILEE BASIN) AMENDMENT BILL 2018 TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS TUESDAY, 5 MARCH 2019 Moranbah Public Hearing—Inquiry into the Mineral Resources (Galilee Basin) Amendment Bill 2018 TUESDAY, 5 MARCH 2019 ____________ The committee met at 6.05 pm. CHAIR: Good evening. I declare open this public hearing for the committee’s inquiry into the Mineral Resources (Galilee Basin) Amendment Bill 2018. I would like to acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we gather today. I would also like to take a moment to acknowledge the recent tragedy that has occurred at the Moranbah North mine and the impact this has had on the community. We extend our sympathy and our thoughts to the Hardwick family and colleagues. On 31 October 2018 Mr Michael Berkman MP, the member for Maiwar, introduced the Mineral Resources (Galilee Basin) Amendment Bill 2018 to the parliament. This bill has been referred to the State Development, Natural Resources and Agricultural Industry Development Committee for examination with a report date of 30 April 2019. Thank you for your interest and your attendance here today. My name is Chris Whiting. I am the member for Bancroft and the chair of the committee. The other committee members here with me today are Mr Pat Weir, deputy chair and member for Condamine; Mr Jim Madden, member for Ipswich West; and Mr Brent Mickelberg, member for Buderim. -

Kit 5 Welcome to Isaac!

Welcome to Isaac Information for our new residents Isaac... helping to energise the world Contents Who We Are ...................................................................... 4 Our Elected Members .................................................... 5 Welcome to Isaac ............................................................ 6 Our Communities ............................................................. 7 Recreation ......................................................................... 8 Exploring Isaac ................................................................ 10 Travelling Isaac ................................................................ 11 Events ................................................................................ 12 Art and Culture ................................................................ 14 Essential Services ........................................................... 16 Council Services ............................................................. 20 Community Facilities ...................................................... 22 Business in Isaac ............................................................ 24 Disaster Management .................................................... 25 Useful Information ........................................................... 26 Connect with Council ..................................................... 27 Disclaimer All information presented in this document is provided in good faith with every effort made to ensure its accuracy. However as Isaac’s communities -

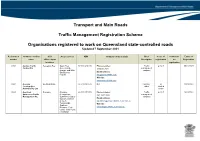

Traffic Management Scheme

Transport and Main Roads Traffic Management Registration Scheme Organisations registered to work on Queensland state-controlled roads Updated 7 September 2021 Registration Company / trading QLD Areas services ABN Company contact details Brief Scope of Conditions Expiry of number name office / depot Description registration on Registration locations registration 0202 Aaction Traffic Deception Bay South East 37 128 649 445 Phone number: Traffic O, S, D 30/11/2023 Control P/L Queensland, 1300 055 619 management Gympie and Wide company Bay Burnett Email address: regions [email protected] Website: www.aactiontraffic.com 0341 Acciona South Brisbane 66 618 030 872 N/A Industry - D 31/01/2023 Construction other Limited Australia Pty Ltd scope 0043 Acquired Brendale Brisbane 45 831 570 559 Phone number: Traffic O, S, D 15/12/2022 Awareness Traffic Metropolitan, (07) 3881 3008 management Management P/L Sunshine Coast to company Gympie, western Email address: areas to [email protected] Toowoomba, Website: Southern Brisbane, Gold www.acquiredawareness.com.au Coast, Gold Coast Hinterland Registration Company / trading QLD Areas services ABN Company contact details Brief Scope of Conditions Expiry of number name office / depot Description registration on Registration locations registration 0278 Action Control Labrador South East 92 098 736 899 Phone Number: Traffic O, S 31/10/2021 (Aust) P/L Queensland 0403 320 558 management Limited company scope Email address: [email protected] Website: www.actioncontrol.com.au 0271 -

Central Queensland Coal Project Chapter 24 – References Supplementary Environmental Impact Statement

Central Queensland Coal Project Chapter 24 – References Supplementary Environmental Impact Statement Central Queensland Coal Project Chapter 24 - References 20 December 2018 CDM Smith Australia Pty Ltd ABN 88 152 082 936 Level 4, 51 Alfred Street Fortitude Valley QLD 4006 Tel: +61 7 3828 6900 Fax: +61 7 3828 6999 Table of Contents 24 References ........................................................................................................................................ 24-2 24.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 24-2 24.2 Project Need and Alternatives ...................................................................................................... 24-3 24.3 Description of the Project ............................................................................................................... 24-3 24.4 Climate ..................................................................................................................................................... 24-4 24.5 Land .......................................................................................................................................................... 24-5 24.6 Traffic and Transport ........................................................................................................................ 24-9 24.7 Waste Management .......................................................................................................................... -

Mackay Isaac Whitsunday Biofutures Investment Prospectus

Investing in Biofutures projects in the Mackay Isaac Whitsunday Region Contents Queensland Government’s 4 biofutures vision The biofuture of Queensland 6 The Mackay Isaac Whitsunday 7 region The Mackay Isaac Whitsunday 8 region’s feedstock profile Existing biofutures businesses 10 Local case study: 11 Wilmar’s integrated biorefinery options at Sarina The companion market approach 12 A region-based precinct concept 13 for biofutures Clean energy investment options 13 Why invest in the Mackay Isaac 14 Whitsunday region? Potential opportunities 16 Support 18 Resources 19 Online references Opportunities 20 Contacts 20 Queensland Biofutures 10-year Roadmap and Action Plan June 2016 statedevelopment.qld.gov.au/resources/plan/biofutures/biofutures-10yr-roadmap-actionplan.pdf Bioenergy state of the nation report, KPMG bioenergyaustralia.org.au/resources/reports--general/ Biofuels to bioproducts: a growth industry for Australia study, QUT research.qut.edu.au/biorefining/publications/biofuels-to-bioproducts-a-growth-industry-for-australia/ Investing in Biofutures Projects in the Mackay Queensland Biomass mapping and data Isaac Whitsunday Region has been produced statedevelopment.qld.gov.au/industry-development/queensland-biomass-mapping-and-data by Aurecon (June 2019). 1 As the Assistant Minister for State Development and Member for Mackay, I invite you to view this prospectus as an opportunity to gain a greater understanding of the biofutures investment options that are available in the Mackay, Isaac and Whitsunday regions of Queensland. This region is one of the fastest growing and dynamic economies in Australia delivering minerals, diverse agricultural products and tourism to the world and contributing around $20 billion in Gross Regional Product (GRP) to the Australian economy. -

Appendix M Social Baseline

Appendix M Social baseline November 2013 This document is in draft form. The contents, including any opinions, conclusions or recommendations contained in, or which may be implied from, this draft document must not be relied upon. GHD reserves the right, at any time, without notice, to modify or retract any part or all of the draft document. To the maximum extent permitted by law, GHD disclaims any responsibility or liability arising from or in connection with this draft document. This North Galilee Basin Rail Project social baseline report (“the Report”) has been prepared by GHD Pty Ltd (“GHD”) on behalf of and for Adani Mining Pty Ltd (“Adani”) in accordance with an agreement between GHD and Adani. The Report may only be used and relied on by Adani for the purpose of informing environmental assessments and planning approvals for the North Galilee Basin Rail Project (“the Purpose”) and may not be used by, or relied on by any person other than Adani. The services undertaken by GHD in connection with preparing the Report were limited to those specifically detailed in this Report. The Report is based on conditions encountered and information reviewed, including assumptions made by GHD, at the time of preparing the Report. Assumptions made by GHD are contained through the Report, including (but not limited to) concept design and operations information provided by Adani. To the maximum extent permitted by law GHD expressly disclaims responsibility for or liability arising from: any error in, or omission in connection with assumptions, or reliance on the Report by a third party, or use of the Report other than for the Purpose. -

Local Government Remuneration Commission Annual Report 2020 2

Local Government Remuneration Commission Annual Report 2020 2 © State of Queensland, December 2020. Published by the Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government, and Planning 1 William Street, Brisbane Qld 4000, Australia. Licence: This work is licensed under the Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 Australia Licence. In essence, you are free to copy and distribute this material in any format, as long as you attribute the work to the State of Queensland (Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government, and Planning) and indicate if any changes have been made. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Attribution: The State of Queensland, State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government, and Planning. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of information. However, copyright protects this publication. The State of Queensland has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered. The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders of all cultural and linguistic backgrounds. If you have difficulty understanding this publication and need a translator, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone the Queensland Department of State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government, and Planning on 13 QGOV (13 74 68). Disclaimer: While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, the State of Queensland accepts no responsibility for decisions or actions taken because of any data, information, statement, or advice, expressed or implied, contained within. -

ECM 4640296 V1 RE

From: Marcus Fossey Sent: Fri, 7 Aug 2020 09:52:49 +1000 To: Damian Pearson;Records Cc: Imelda Caple;Donna Skinner Subject: RE: MCU 20 0002 Response to Information Request 160 Walshs Road Nebo Attachments: 200807 - Response to Information Request_IRC.pdf, 200603 Ownership & Vehicle assessment.pdf, RW-001 WALSHS ROAD REV 2.pdf Hi Damien Please see attached information request response. We intend on commencing Public Notification in due course. I intend on using Sheet 2 on the current proposal plan as attached. Hi Donna, Can you please confirm adjoining landowners for our letters. Thanks, Marcus Marcus Fossey Senior Town Planner [email protected] T 07 4957 9702 M +61 427920475 PO Box 158 83 Wood St Mackay QLD 4740 Australia Follow us on VERIS.COM.AU The information transmitted may be confidential, is intended only for the person to which it is addressed, and may not be reviewed, retransmitted, disseminated or relied upon by any other persons. If you received this message in error, please contact the sender and destroy any paper or electronic copies of this message. Views expressed in this email are those of the individual, except where the sender specifically states otherwise. Veris does not guarantee that the communication is free of errors, virus or interference. From: Damian Pearson [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: Monday, 6 July 2020 4:26 PM To: Marcus Fossey <[email protected]> Document Set ID: 4640296 Version: 1, Version Date: 07/08/2020 Cc: Imelda Caple <[email protected]>; Donna Skinner <[email protected]> Subject: RE: MCU 20 0002 Response to Information Request 160 Walshs Road Nebo Hello Marcus, Council agrees to an extension of the information request until 1 October 2020. -

View the Desktop Matrix

The impacts of resource sector growth desktop matrix March 2013 in regional communities Stage 1 Acknowledgments Disclaimer This project was funded by the Australian This study has been produced in collaboration between the three Department of Regional Australia, Regional Development Australia organisations of Mackay Isaac Local Government, Arts and Sport, and Whitsunday, Fitzroy and Central West and Wide Bay Burnett. supported by the Queensland government. CQUniversity’s Sustainable Regional Development Research Programme We gratefully acknowledge CQUniversity was commissioned to undertake the desktop review and stakeholder colleagues Dr Delwar Akbar, Dr Zobaidul consultation exercises, as well as to assist the RDAs in forming the Kabir, Lindsay Greer for their contributions recommendations and action areas emerging from the study. in designing the stakeholder consultation survey; and Gail Tucker for her assistance While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, RDA and with maps and report formatting. We CQUniversity accepts no responsibility for decisions or actions taken also thank the over one hundred regional as a result of any data, information, statement or advice, expressed or stakeholders who participated in the implied, contained within. To the best of our knowledge, the content consultation phase of this project. was correct at the time of publishing. Any references to legislation are not an interpretation of the law and are to be used as a guide only. Table of Contents Abbreviations ..........................................................................................................................................4 -

November 2019 LAWMAC Newsletter

Issue: November 2019 Hinchinbrook Shire Council Hinchinbrook hosts LAWMAC August workshop and AGM Wednesday 21 August 2019, a wonderful afternoon to commence the LAWMAC three (3) day workshop and conference, with 30 guests including; members, visitors and guest speakers undertaking a field trip at the Wilmar Victoria Sugar Mill. The Regional Operations Manager Mr Adam Douglas provided an insightful and attention-grabbing tour and presentation on Waste Management in Sugar Manufacturing and Co-Generation Opportunities. Members, visitors and guests viewing Wilmar Sugar facilities Wilmar Mill Tour – Workshop and Site Visit Hinchinbrook Shire Council Cr Lancini inside Victoria Mill Full Day Workshop Members, visitors and guests’ in-front of Victoria Mill Thursday 22 August 2019, a picturesque morning for 52 members at the TYTO Conference Centre, a facility which offers the unexpected discovery of art, culture, nature and knowledge. The workshop was a positive display of diverse and captivating presentations exploring resource recovery challenges and opportunities. LAWMAC Secretary: Mary Field - PO Box 47, Manunda QLD 4870 mobile: 0409 536 379 email: [email protected] web: www.lawmac.org.au Issue: November 2019 Hinchinbrook Shire Council Cr Milton with members, participating in a group based task Lucinda Foreshore dnner and evening entertainment event The Honorable Trevor Evans MP – Assistant Minster for Waste Reduction\and Enviornmental Management participing in a group based task. Dinner and Evening Entertainment – Lucinda Jetty Thursday evening following the full day workshop a sunset beach dinner party with evening entertainment was hosted on the foreshore of Lucinda Jetty. The sunset made for a relaxing atmosphere with fine dining and a live band before Sample of the delicious food on offer Friday’s AGM and general meeting. -

Isaac Regional Council Planning Scheme Priority Infrastructure Area Isaac Region

Draft Isaac Regional Council Planning Scheme Priority Infrastructure Area Isaac Region W H IT S U N D A Y R E G IO N A L C O U N C IL Zones Low Density Residential M A C K A Y R E G IO N A L C O U N C IL Low-medium Density Residential Centre CHARTERS TOWERS REGIONAL COUNCIL Industry Industry Investigation Glenden Recreation and Open Space Environmental Management and Conservation Community Facilities Emerging Community Limited Development Nebo Town Rural Residential Ilbilbie Rural Specialised Centre Carmilla Special Purpose # Tourism Area (Minor) Moranbah Township Precinct Boundary Cadastral Boundary Nebo Rural Local Government Boundary Waterway Railway Network General Clermont Rural Priority Infrastructure Area St Lawrence Projection Area Boundary Dysart DIGITAL CADASTRAL DATA BASE - BOUNDARY & TERRAIN INFORMATION. Based on or contains data provided by the State of Queensland (Department of Natural Resources and Mines) [2017 to 2019]. In consideration of the State permitting use of this data you acknowledge and agree that the State gives no # warranty in relation to the data (including accuracy, reliability, completeness, Middlemount currency or suitability) and accepts no liability (including without limitation, Clermont Town liability in negligence) for any loss, damage or costs (including consequential damage) relating to any use of the data. Data must not be used for direct marketing or be used in breach of the privacy laws. LIV IN G S T O N E S H IR E C OGeocentric U NDatum Cof Australia IL (GDA94) 12/03/2020 °! Approx Scale @ A3