Cases on Procedure Annotated, Trial and Appellate Practice, By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Appeal Bond Reforms Protect Defendants' Due

WLF Legal Backgrounder Washington Legal Foundation Advocate for freedom and justice® 2009 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 202.588.0302 Vol. 19 No. 42 November 12, 2004 STATE APPEAL BOND REFORMS PROTECT DEFENDANTS’ DUE PROCESS RIGHTS by Glenn G. Lammi and Justin P. Hauke Over the past several years, defendants in civil litigation have pursued reform of state laws and rules which require them to post a bond prior to appealing an adverse judgment. Reform proponents have not taken issue with the requirement. Rather, they have sought reasonable reductions in the amount of the bond which, considering the skyrocketing damage awards that have now become commonplace, threaten their fundamental right to appeal. This LEGAL BACKGROUNDER will examine the appeal bond requirement, the factors which have contributed to the push for reform, the types of changes that have been adopted, and what additional steps may be taken to protect defendants’ rights. “Supersedeas” Bonds. In all but five states,1 defendants wishing to appeal adverse verdicts must post a “supersedeas” bond with the presiding trial court. Such bonds protect plaintiffs by guaranteeing that a civil defendant will have assets sufficient to satisfy the judgment if appeal efforts ultimately fail. Some jurisdictions have allowed the trial judge to set the amount of the bond. Laws in other states required that presiding judges impose a bond of at least 100% of the judgment, plus fees, interest, and costs. Many of those laws also denied judges the discretion to reduce or waive the bond. Notably, states have never imposed any similar financial responsibilities on plaintiffs who wish to appeal verdicts. -

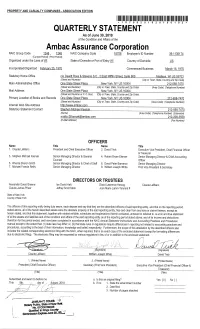

Ambac Assurance Corporation ASSETS Current Statement Date 4 1 2 3 Net Admitted December 31 Nonadmitted Assets Prior Year Net Assets Assets (Cols

PROPERTY AND CASUALTY COMPANIES - ASSOCIATION EDITION 11111 11111 1 11111111 11 II II 11111111 1111111 18 08 11 12 0 1 0 0 1 0 2 * QUARTERLY STATEMENT As of June 30, 2018 of the Condition and Affairs of the Ambac Assurance Corporation NAIC Group Code 1248, 1248 NAIC Company Code 18708 Employer's ID Number 39-1135174 (Current Period) (Prior Period) Organized under the Laws of WI State of Domicile or Port of Entry WI Country of Domicile US Incorporated/Organized February 25, 1970 Commenced Business . March 16, 1970 Statutory Home Office c/o Dewitt Ross & Stevens S.C., 2 East Mifflin Street, Suite 600 Madison, WI US 53703 (Street and Number) (City or Town, State, Country and Zip Code) Main Administrative Office One State Street Plaza New York, NY US 10004 212-658-7470 (Street and Number) (City or Town, State, Country and Zip Code) (Area Code) (Telephone Number) Mail Address One State Street Plaza New York, NY US 10004 (Street and Number or P. 0. Box) (City or Town, State, Country and Zip Code) Primary Location of Books and Records One State Street Plaza New York, NY US 10004 212-658-7470 (Street and Number) (City or Town, State, Country and Zip Code) (Area Code) (Telephone Number) Internet Web Site Address http://www.ambac.com Statutory Statement Contact Stephen Michael Ksenak 212-658-7470 (Name) (Area Code) (Telephone Number) (Extension) mailto:SKsenakQambac.com 212-208-3558 (E-Mail Address) (Fax Number) OFFICERS Name Title Name Title 1 . Claude LeBlanc President and Chief Executive Officer 2. David Trick Executive Vice President, Chief Financial Officer & Treasurer 3. -

Superseding Money Judgments in Texas: Four Proposed Reforms to Help the Business Litigant and to Further Improve the Texas Civil Justice System

St. Mary's Law Journal Volume 51 Number 1 Article 3 1-2020 Superseding Money Judgments in Texas: Four Proposed Reforms to Help the Business Litigant and to Further Improve the Texas Civil Justice System James Holmes Holmes PLLC Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/thestmaryslawjournal Part of the Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons, Civil Law Commons, Civil Procedure Commons, Corporate Finance Commons, Courts Commons, Legal Remedies Commons, Legislation Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation James Holmes, Superseding Money Judgments in Texas: Four Proposed Reforms to Help the Business Litigant and to Further Improve the Texas Civil Justice System, 51 ST. MARY'S L.J. 69 (2020). Available at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/thestmaryslawjournal/vol51/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the St. Mary's Law Journals at Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. Mary's Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Holmes: Superseding Money Judgments in Texas ARTICLE SUPERSEDING MONEY JUDGMENTS IN TEXAS: FOUR PROPOSED REFORMS TO HELP THE BUSINESS LITIGANT AND TO FURTHER IMPROVE THE TEXAS CIVIL JUSTICE SYSTEM JAMES HOLMES* I. Introduction ............................................................................................. 71 II. The Problems Under the Existing Supersedeas Laws ....................... 77 A. The Acute Insensitivity of Present Supersedeas Laws for Smaller Business Litigation Defendants, Particularly as They Are Found in Texas ............................................................... 77 B. The Problem with Trial-Court Discretion in Present Supersedeas Practice, and the Difficulty of Obtaining Appellate Relief ............................................................................... -

A Plea of Infancy, Interposed for the Purpose of Defeating an Action

B Baby Act. A plea of infancy, interposed for the tively. A determination by a judicial or quasi judicial purpose of defeating an action upon a contract made body that an employee is entitled to accrued but while the person was a minor, is vulgarly called uncollected salary or wages. Such may be awarded "pleading the baby act". By extension, the term is in employment discrimination cases. applied to a plea of the statute of limitations. Back-seat driver. A highly nervous passenger whether Bachelor. One who has taken the first undergraduate sitting in rear or by driver, who by unwarranted degree (baccalaureate) in a college or university. advice and warnings interferes in careful operation of An unmarried man. A kind of inferior knight; an automobile. esquire. Backside. In English law, a term formerly used in Back, v. To indorse; to sign on the back; to sign conveyances and also in pleading; it imports a yard generally by way of acceptance or approval; to sub at the back part of or behind a house, and belonging stantiate; to countersign; to assume financial re thereto. sponsibility for. In old English law where a warrant issued in one county was presented to a magistrate of Backspread. Less than normal price difference in arbi another county and he signed it for the purpose of trage. making it executory in his county, he was said to "back" it. Back taxes. Those assessed for a previous year or years and remaining due and unpaid from the original Back, adv. To the rear; backward; in a reverse di tax debtor. -

SC11-1611 Appendix to Amici Curiae Brief (American Tort Reform

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA Case No. SC11-1611 L.T. No.: 1D10-2820 __________________________________________________________________ AMANDA JEAN HALL, PETITIONER, v. R.J. REYNOLDS TOBACCO COMPANY, RESPONDENT. __________________________________________________________________ APPENDIX TO BRIEF OF THE AMERICAN TORT REFORM ASSOCIATION AND THE FLORIDA JUSTICE REFORM INSTITUTE AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENT __________________________________________________________________ On Discretionary Review from a Decision of the First District Court of Appeal of Florida __________________________________________________________________ George N. Meros, Jr. Florida Bar No. 263321 Charles Burns Upton II Florida Bar No. 0037241 GrayRobinson, P.A. Post Office Box 11189 Tallahassee, Florida 32302-3189 Telephone: 850-577-9090 Facsimile: 850-577-3311 Email: [email protected] [email protected] INDEX TO APPENDIX Page SUMMARY OF LEGISLATION AND COURT RULES LIMITING THE SIZE OF APPEAL BONDS ................................................................. A-1 APPENDIX SUMMARY OF LEGISLATION AND COURT RULES LIMITING THE SIZE OF APPEAL BONDS Jurisdictions That Have Not Adopted Legislation Or Court Rules Limiting The Size Of Appeal Bonds Alaska Maryland Delaware Montana District of Columbia New York Illinois Enacted Or Adopted Appeal Bond Legislation Or Court Rules State Statute / Date To Whom Limits Amount of Appeal Scope of Appeal Bond Rule / Bill Approved Apply Bond Limit Limit Alabama Ala. Code § 6- 2/24/2006 Master Settlement $125,000,000 Applies to civil litigation 12-4 Agreement under any legal theory. signatories, successors, and affiliates Arizona Ariz. Code § 4/13/2011 All litigants The lesser of the Applies to all judgments 12-2108 total amount of in a civil action under created by damages any legal theory. S.B. 1212 (excluding punitive damages), 50% of the defendant’s net worth, or $25,000,000 Arkansas Ark Code 3/27/2003 All litigants $25,000,000 Applies to all judgments § 16-55-214 3/30/2005 in civil litigation amended by regardless of legal S.B. -

Guide for Self-Represented (“Pro Se” Or “Pro Per”) Appellants and Appellees Revised Edition 2019

Guide for Self-Represented (“Pro Se” or “Pro Per”) Appellants and Appellees Revised Edition 2019 BASIC INFORMATION ABOUT CIVIL APPEALS IN THE ARIZONA COURT OF APPEALS AND THE ARIZONA SUPREME COURT The office hours for the courts listed below are 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., Monday through Friday, except on official state holidays. Arizona Supreme Court 1501 W. Washington St. Phoenix, AZ 85007 Clerk: (602) 452-3396 http://www.azcourts.gov Arizona Court of Appeals Arizona Court of Appeals Division One Division Two 1501 W. Washington St. 400 W. Congress St. Phoenix, AZ 85007 Tucson, AZ 85701 Clerk: (602) 452-6700 Clerk: (520) 628-6954 http://www.azcourts.gov/coa1 http://www.appeals2.az.gov Page I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... iii II. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS, DISCLAIMER, ELECTRONIC FILING ............................. .iv III. ARIZONA COURT SYSTEM FLOW CHART ............................................................... v IV. ARIZONA APPEALS FLOW CHART ............................................................................ vi V. THE STEPS TO FILING AN APPEAL .............................................................................. 1 Step 1: Determine when the Final Judgment was Entered by the Clerk of the Superior Court .......................................................................... 1-2 Step 2: Timely File a “Notice of Appeal” From the Final Judgment .................................. 2-3 Step 3: Decide whether a “Cross-Appeal” -

Arizona Court of Appeals Division One

NOTICE: NOT FOR PUBLICATION. UNDER ARIZONA RULE OF THE SUPREME COURT 111(c), THIS DECISION DOES NOT CREATE LEGAL PRECEDENT AND MAY NOT BE CITED EXCEPT AS AUTHORIZED. IN THE ARIZONA COURT OF APPEALS DIVISION ONE CITY CENTER EXECUTIVE PLAZA, L.L.C.; INFORMATION SOLUTIONS, INC.; JERRY and CINDY ALDRIDGE, Petitioners, v. THE HONORABLE LEE F. JANTZEN, Judge of the SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF ARIZONA, in and for the County of MOHAVE, Respondent Judge, BRIAN THIENES, an individual; JOHN BALL and MONICA BALL, husband and wife; THE THOMPSON FAMILY TRUST; JUAN BRACAMONTE and JACQUELINE BRACAMONTE, husband and wife; THE REFUGE COMMUNITY ASSOCIATION, INC., Real Parties in Interest. No. 1 CA-SA 14-0090 Petition for Special Action from the Superior Court in Mohave County No. S8015CV2011001563 The Honorable Lee F. Jantzen, Judge JURISDICTION ACCEPTED; RELIEF GRANTED IN PART COUNSEL Perkins Coie LLP, Phoenix By Daniel C. Barr, John H. Gray, Joshua M. Crum, Alexander W. Samuels Counsel for Petitioners Beus Gilbert PLLC, Phoenix By Franklyn D. Jeans, Cory L. Broadbent, Lyn Anne Bailey Counsel for Real Parties in Interest Thienes, Ball, Thompson Family Trust and Bracamonte Ekmark & Ekmark, L.L.C., Scottsdale By Penny L. Koepke, Nicole A. Miller, Solomon S. Krotzer Counsel for Real Party in Interest The Refuge Community Association, Inc. DECISION ORDER Judge Michael J. Brown delivered the decision of the Court, in which Presiding Judge Randall M. Howe and Judge Jon W. Thompson joined. B R O W N, Judge: ¶1 This special action involves a challenge to the superior court’s determination of the amount of a supersedeas bond. -

The Appeal Bond—What It Is, How It Works, and Why It Needs to Be Factored Into Your Litigation Strategy

The Appeal Bond—What It Is, How It Works, and Why It Needs to Be Factored Into Your Litigation Strategy 24 When a business is hit with a bet-the-company product liability law- suit—for instance, a putative nationwide or statewide class action— the defendant and its lawyers spend a lot of time at the outset thinking about case strategy and putting dollar-and-cent values on a range of issues. What will it cost to defend the lawsuit? Is the com- pany likely to get a fair shake in the forum and, if not, is it possible to change the venue? Who makes up the potential jury pool, and what is the range of jury verdicts in the jurisdiction? What are the odds of winning or losing at trial and on appeal? Based on all of the known factors, is the case one that should be settled or tried? by Richard G. Stuhan and Sean P. Costello But one question that often is not asked early in the case is one some form of bond in order to appeal an adverse judgment whose answer can fundamentally change the strategy of the and stay the plaintiff’s execution of that judgment. case: How much will it cost the defendant to appeal an adverse judgment? We’re not talking about attorneys’ fees or the asso- Failing to take the appeal bond into account in the early ciated costs of appeal, although these are important consider- stages of case evaluation and strategy can put a defendant ations. Instead, we’re talking about the bond a losing defendant and its lawyers in a very uncomfortable position if, despite must pay to secure its right to appeal and stay the judgment. -

A Cap on the Defendant's Appeal Bond?

RENDLEMANFINAL.DOC5 2/26/2007 9:40:50 AM A CAP ON THE DEFENDANT’S APPEAL BOND?: PUNITIVE DAMAGES TORT REFORM Doug Rendleman* In the spring of 2006, “Appeal Bond Reform,” was the first subject on the American Tort Reform Association’s website entry for “Issues.”1 That entry may draw a blank and spur a curious Web-surfer to ask, “What’s an appeal bond?” and “OK, why does the appeal bond need reformed?” I. ITINERARY To inquire into the world of the appeal bond, to ask how it came to the American Tort Reform Association agenda, to trace its history as tort reform, and to draw some constitutional and public policy lessons are my modest goals for this article. The appeal bond has been an issue in huge-damages litigation. I * Huntley Professor, Washington and Lee. This article, which was a long time in gestation, began with my critical report on Virginia’s and the other tobacco-states’ “first wave” of appeal-bond capping statutes in the 2001 annual supplement to DOUG RENDLEMAN, ENFORCEMENT OF JUDGMENTS AND LIENS IN VIRGINIA (2d ed. 1994). Although the piece retains some Virginia attributes, enthusiastic and zealous research assistants, Ms. Bryony Renner, Mr. Andrew Howard and Mr. Tim Dooley caught the “second wave” of tort-reform capping statutes and transmogrified it to a national article. Mr. Howard’s and Mr. Dooley’s extraordinary computer research on the state appeal-bond rules and statutes and their legislative histories broadened, expanded, and heightened my research and writing. Ms. Rachel Sederquest assisted with citations in the summer of 2006. -

A Cap on the Defendant's Appeal Bond?: Punitive Damages Tort Reform Doug Rendleman

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals July 2015 A Cap on the Defendant's Appeal Bond?: Punitive Damages Tort Reform Doug Rendleman Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Rendleman, Doug (2006) "A Cap on the Defendant's Appeal Bond?: Punitive Damages Tort Reform," Akron Law Review: Vol. 39 : Iss. 4 , Article 10. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol39/iss4/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Rendleman: Appeal Bond Tort Reform RENDLEMANFINAL.DOC5 2/26/2007 9:40:50 AM A CAP ON THE DEFENDANT’S APPEAL BOND?: PUNITIVE DAMAGES TORT REFORM Doug Rendleman* In the spring of 2006, “Appeal Bond Reform,” was the first subject on the American Tort Reform Association’s website entry for “Issues.”1 That entry may draw a blank and spur a curious Web-surfer to ask, “What’s an appeal bond?” and “OK, why does the appeal bond need reformed?” I. ITINERARY To inquire into the world of the appeal bond, to ask how it came to the American Tort Reform Association agenda, to trace its history as tort reform, and to draw some constitutional and public policy lessons are my modest goals for this article. -

Vol 3 Public Law3

The National Law Library Volume Three PublicPublicPublic LawLawLaw by Howard L. Bevis William Ziegler Professor of Govermnent and Law Harvard Universi:y Originally published in 1939, by P. F. C OLLIER & SON CORPORATION TP Printed In The United States Of America ANTI N SHYSTER EWS M NationalAnno Law Domini LibraryAGAZINE 2000 Vol. 3 Black’s Law Dictionary defines “shyster” as “one who carries on Creator, Proprietor & any business, especially“AntiShyster” a legal business, defined: in a dishonest way. Christian Publisher An unscrupulous practitioner who disgraces his profession by doing mean work, and resorts to sharp practice to do it.” Alfred Adask Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary defines “shyster” as adask@gte “one who is professionally unscrupulous esp. in the practice of law or politics.” For the purposes of this publication, a “shyster” is a dishonest attorney or politician, i.e., one who lies. An POB 540786 Dallas,.net Texas 75354-0786 “AntiShyster”, therefore, is a person, an institution, or in this case, 972-418-8993 a news magazine that stands in sharp opposition to lies and to The United States of America professional liars, especially in the arenas of law and politics. Original Preface Any attemptThe ONLY to cope legal with advice our thismodern publication judicial offerssystem is this:must be tempered with the sure andLegal certain knowledgeAdvice that “law” is always The growing importance of public a crapshoot. That is, nothing (not even brown paper bags filled law in the United States has brought with hundred dollar bills and handed to the judge) will absolutely the subject to the attention of both law- guarantee your victory in a judicial trial or administrative hearing. -

The Applicability of State Appeal Bond Caps in Suits Brought in Federal Courts Pursuant to Diversity Jurisdiction

COMMENT THE APPLICABILITY OF STATE APPEAL BOND CAPS IN SUITS BROUGHT IN FEDERAL COURTS PURSUANT TO DIVERSITY JURISDICTION JESSE WENGER† INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 980 I. OVERVIEW OF SUPERSEDEAS BONDS IN FEDERAL AND STATE COURTS ........................................................................ 981 A. Staying a Judgment on Appeal in Federal Court .............................. 982 1. Brief History of Supersedeas Practice in the Federal Courts ................................................................... 983 2. Current Approach to Supersedeas Practice in the Federal Courts ................................................................... 984 B. Staying Judgments on Appeal in the State Courts and the Push for Appeal Bond Reform ....................................................... 986 1. Motivation for Appeal Bond Reform .................................. 987 2. Varieties of Appeal Bond Reform Statutes and Their Underlying Rationales .............................................. 989 II. BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE COURT’S ERIE DOCTRINE EVOLUTION ............................................................................. 990 A. The Evolution of the Court’s Hanna-Prong Analysis ....................... 992 B. The Evolution of the Court’s RDA-Prong Analysis .......................... 994 1. Outcome-Determinative Approach ..................................... 994 † Senior Editor, Volume 162, University of Pennsylvania Law Review. J.D. Candidate, 2014, University of Pennsylvania