ATRA's Tort Reform Record

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unity in Tort, Contract, and Property: the Model of Precaution

California Law Review VOL. 73 JANUARY 1985 No. 1 Copyright © 1985 by California Law Review, Inc. Unity in Tort, Contract, and Property: The Model of Precaution Robert Cootert Much of the common law is concerned with allocating the costs of harm, such as the harm caused by accidents, nuisances, breaches of con- tract, or governmental takings of private property. There are at least two distinct goals for adopting allocative cost rules: the equity goal of com- pensating victims and the efficiency goal of minimizing costs to society as a whole.' These goals in turn can be formulated as two principles: the compensation principle and the marginal principle. The compensation principle states that victims should be compensated for harm caused by others. The marginal principle states that social costs should be mini- mized by equating the incremental benefit of each precautionary activity to its incremental cost. Is the common law primarily concerned with the justice of compen- sation or the efficiency of cost minimization? Presented this way, the two principles appear to be rival theories of law.' This Article, however, poses a different question: How does the common law combine the goal of compensation with the goal of minimizing social costs? The two prin- ciples now appear as complementary, rather than rival, explanations. As a result, this Article assumes that there are circumstances in which com- pensation is required for reasons of justice and examines mechanisms t Professor of Law, Boalt Hall School of Law, University of California, Berkeley. B.A. 1967, Swarthmore College; B.A. 1969, Oxford University; Ph.D. -

Elements of Negligence Under the Tort of Negligence, There Are Four Elements a Plaintiff Must Establish to Succeed in Holding a Defendant Liable

Elements of Negligence Under the tort of negligence, there are four elements a plaintiff must establish to succeed in holding a defendant liable. The Court of Appeals of Georgia outlined the elements for a prima facie case of negligence in Johnson v. American National Red Cross as follows: “(1) a legal duty to conform to a standard of conduct; (2) a breach of this duty; (3) a causal connection between the conduct and the resulting injury; and (4) damage to the plaintiff.” Johnson, 569 S.E.2d 242, 247 (Ga. App. 2002). Under the first element, a legal duty to a standard of due care, the plaintiff must prove the defendant had a duty to conform to a standard of conduct for protection of the plaintiff against an unreasonable risk of injury. The duty of care will be determined by the applicable standard of care and several factors can heighten the standard of care depending upon the relationship between the parties, whether the plaintiff was foreseeable, the profession of the defendant, etc. For example, the Red Cross has a duty, when supplying blood donations to hospitals, to make its best efforts to ensure blood supplied is not tainted with any transferable viruses or diseases, such as an undetectable rare strain of HIV. A breach of the duty of care occurs when the defendant’s actions do not meet the required level of applicable standard of care due to the plaintiff. Whether a breach of the duty of the applicable standard of care occurs is a question for the trier of fact. -

Municipal Tort Liability -- "Quasi Judicial" Acts

University of Miami Law Review Volume 14 Number 4 Article 8 7-1-1960 Municipal Tort Liability -- "Quasi Judicial" Acts Edwin C. Ratiner Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Recommended Citation Edwin C. Ratiner, Municipal Tort Liability -- "Quasi Judicial" Acts, 14 U. Miami L. Rev. 634 (1960) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol14/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUNICIPAL TORT LIABILITY-"QUASI JUDICIAL" ACTS Plaintiff, in an action against a municipality for false imprisonment, alleged that lie was arrested by a municipal police officer pursuant to a warrant known to be void by the arresting officer and the municipal court clerk who acted falsely in issuing the warrant. Held: because the acts alleged were "quasi judicial" in nature, the municipality was not liable under the doctrine of respondeat superior. Middleton Y. City of Fort Walton Beach, 113 So.2d 431 (Fla. App. 1959). The courts uniformly agree that the tortious conduct of a public officer committed in the exercise of a "judicial" or "quasi judicial"' function shall not render either the officer or his municipal employer liable.2 The judiciary of superior and inferior courts are generally accorded immunity from civil liability arising from judicial acts and duties performed within the scope of the court's jurisdiction. -

The United States Supreme Court Adopts a Reasonable Juvenile Standard in J.D.B. V. North Carolina

THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT ADOPTS A REASONABLE JUVENILE STANDARD IN J.D.B. V NORTH CAROLINA FOR PURPOSES OF THE MIRANDA CUSTODY ANALYSIS: CAN A MORE REASONED JUSTICE SYSTEM FOR JUVENILES BE FAR BEHIND? Marsha L. Levick and Elizabeth-Ann Tierney∗ I. Introduction II. The Reasonable Person Standard a. Background b. The Reasonable Person Standard and Children: Kids Are Different III. Roper v. Simmons and Graham v. Florida: Embedding Developmental Research Into the Court’s Constitutional Analysis IV. From Miranda v. Arizona to J.D.B. v. North Carolina V. J.D.B. v. North Carolina: The Facts and The Analysis VI. Reasonableness Applied: Justifications, Defenses, and Excuses a. Duress Defenses b. Justified Use of Force c. Provocation d. Negligent Homicide e. Felony Murder VII. Conclusion I. Introduction The “reasonable person” in American law is as familiar to us as an old shoe. We slip it on without thinking; we know its shape, style, color, and size without looking. Beginning with our first-year law school classes in torts and criminal law, we understand that the reasonable person provides a measure of liability and responsibility in our legal system.1 She informs our * ∗Marsha L. Levick is the Deputy Director and Chief Counsel for Juvenile Law Center, a national public interest law firm for children, based in Philadelphia, Pa., which Ms. Levick co-founded in 1975. Ms. Levick is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and Temple University School of Law. Elizabeth-Ann “LT” Tierney is the 2011 Sol and Helen Zubrow Fellow in Children's Law at the Juvenile Law Center. -

Specific Tort Paper Code: L-4006 Topic : Deceit Or Fraud

LL.M. IV SEMESTER SUBJECT: SPECIFIC TORT PAPER CODE: L-4006 TOPIC : DECEIT OR FRAUD The making of a representation which a partly knows to be untrue and which is intended or calculated to induce another to act on the faith of it so that he may incur damage is fraud in law. Defined in Polhill v. Walter In case of Derry v. Peek, Lord Herschell laid down rules to recognize deceit: First In order to sustain an action of deceit, there must be proof of fraud Second Fraud in proved when it is shown that a false representation has been mad (1) Knowingly (2) Without belief in its truth (3) Recklessly, careless whether it is true or false. Third If fraud is proved the motive of the person guilty of it is immaterial. To create right of action for deceit there must be a fraudulent representation and representation in order to be fraudulent must be: (1) Which is untrue in fact (2) Which defendant knows to be untrue (3) Which was intended or calculated to induce plaintiff as third person (4) Which the plaintiff or the third person acts on and suffers damages. Fraud by Agent- The fraud of an agent acting within scope of his employment is the fraud of the principal. (1) The principal knows that representation to be false. (a) He authorize the making of it. (b) The representation was made in the general course of his employment without specific authorization them principal will be held liable. (2) The Principal thinks the representation to be true. -

State Appeal Bond Reforms Protect Defendants' Due

WLF Legal Backgrounder Washington Legal Foundation Advocate for freedom and justice® 2009 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20036 202.588.0302 Vol. 19 No. 42 November 12, 2004 STATE APPEAL BOND REFORMS PROTECT DEFENDANTS’ DUE PROCESS RIGHTS by Glenn G. Lammi and Justin P. Hauke Over the past several years, defendants in civil litigation have pursued reform of state laws and rules which require them to post a bond prior to appealing an adverse judgment. Reform proponents have not taken issue with the requirement. Rather, they have sought reasonable reductions in the amount of the bond which, considering the skyrocketing damage awards that have now become commonplace, threaten their fundamental right to appeal. This LEGAL BACKGROUNDER will examine the appeal bond requirement, the factors which have contributed to the push for reform, the types of changes that have been adopted, and what additional steps may be taken to protect defendants’ rights. “Supersedeas” Bonds. In all but five states,1 defendants wishing to appeal adverse verdicts must post a “supersedeas” bond with the presiding trial court. Such bonds protect plaintiffs by guaranteeing that a civil defendant will have assets sufficient to satisfy the judgment if appeal efforts ultimately fail. Some jurisdictions have allowed the trial judge to set the amount of the bond. Laws in other states required that presiding judges impose a bond of at least 100% of the judgment, plus fees, interest, and costs. Many of those laws also denied judges the discretion to reduce or waive the bond. Notably, states have never imposed any similar financial responsibilities on plaintiffs who wish to appeal verdicts. -

Civil Dispositive Motions: a Basic Breakdown

Civil Dispositive Motions: A Basic Breakdown 1) Simplified Timeline: Motion for 12(b)(6) Motions JNOV** Summary Judgment Motions* Motion for New Trial Motion Motion for D.V. for D.V. (Rul 10 days Discovery and Mediation Plaintiff‟s Defendant‟s Evidence Evidence Process Complaint Trial Jury‟s Entry of Judgment Filed Begins Verdict * Defendant may move at any time. Plaintiff must wait until 30 days after commencement of action. **Movant must have moved for d.v. after close of evidence. 2) Pre-Trial Motions: Rule 12(b)(6) and Summary Judgment A. Rule 12(b)(6) Motions to Dismiss 1. Challenge the sufficiency of the complaint on its face. Movant asks the court to dismiss the complaint for “failure to state a claim upon which relief may be granted.” 2. Standard: The court may grant the motion if the allegations in the complaint are insufficient or defective as a matter of law in properly stating a claim for relief. For example: a) The complaint is for fraud, which requires specific pleading, but a required element of fraud is not alleged. 1 b) The complaint alleges breach of contract, but incorporates by reference (and attaches) a contract that is unenforceable as a matter of law. c) The complaint alleges a claim against a public official in a context in which that official has immunity as a matter of law. 3. The court only looks at the complaint (and documents incorporated by reference). a) If the court looks outside the complaint, the motion is effectively converted to a summary judgment and should be treated under the provisions of Rule 56. -

State Judicial Profiles by County 2019-2020

ALWAYS KNOW WHAT LIES AHEAD STATE JUDICIAL PROFILES BY COUNTY 2019-2020 PREPARED BY THE MEMBER FIRMS OF ® ® USLAW NETWORK STATE JUDICIAL PROFILE BY COUNTY USLAW is your home field advantage. The home field advantage comes from knowing and understanding the venue in a way that allows a competitive advantage – a truism in both sports and business. Jurisdictional awareness is a key ingredient to successfully operating throughout the United States and abroad. Knowing the local rules, the judge, and the local business and legal environment provides our firms’ clients this advantage. USLAW NETWORK bring this advantage to its member firms’ clients with the strength and power of a national presence combined with the understanding of a respected local firm. In order to best serve clients, USLAW NETWORK biennially updates its county- by-county jurisdictional profile, including key court decisions and results that change the legal landscape in various states. The document is supported by the common consensus of member firm lawyers whose understanding of each jurisdiction is based on personal experience and opinion. Please remember that the state county-by-county comparisons are in-state comparisons and not comparisons between states. There are a multitude of factors that go into such subjective observations that can only be developed over years of experience and participation. We are pleased on behalf of USLAW NETWORK to provide you with this jurisdictional snapshot. The information here is a great starter for discussion with the local USLAW member firm on how you can succeed in any jurisdiction. This conversation supplements the snapshot because as we all know as with many things in life, jurisdictions can change quickly. -

The Evolution of Australian Competition Law

The Evolution of Australian Competition Law CONTENTS The origins of competition law 11 Limitations of the common law 3 Antitrust statutes in the United States 6 Developments in Australia 9 European Union 23 The origins of competition law Competition law can be traced back to ancient times. Thus, for example, the fi rst attempt to comprehensively codify the law, the eighteenth-century bce Babylonian Code of Hammurabi, contains rules that can be interpreted as curtailing the power of monopolists to engage in price gouging, and in the fi fth century ce the East Roman Emperor Zeno prohibited and exiled monopolists in terms remarkably similar to those used in modern statutes. More recently, and closer to the source of modern Australian law, it is possible to discern in the early English common law at least three lines of attack on anti-competitive conduct.1 Attacks on monopolies Before the Case of Monopolies—Darcy v Allein (1602) 77 ER 1260, the Crown had a practice of granting monopolies in certain lines of trade. These allowed the grantee to engage in a particular trade, without competition, in exchange for royalties paid to the Crown. Darcy v Allein (1602) 77 ER 1260 Court of Kings Bench [Darcy held letters patent from the Crown granting him the exclusive right to import, make and sell playing cards in England for 21 years. Contrary to this grant, Allein made and imported playing cards and sold them to consumers. Darcy thereupon took proceedings against Allein for infringing his letters patent. The fi rst issue that arose was whether their grant was valid.] 1 For a more detailed examination of this topic, see Letwin, ‘The English Common Law Concerning Monopolies’ 21 University of Chicago Law Review 355 (1954). -

Initial Stages of Federal Litigation: Overview

Initial Stages of Federal Litigation: Overview MARCELLUS MCRAE AND ROXANNA IRAN, GIBSON DUNN & CRUTCHER LLP WITH HOLLY B. BIONDO AND ELIZABETH RICHARDSON-ROYER, WITH PRACTICAL LAW LITIGATION A Practice Note explaining the initial steps of a For more information on commencing a lawsuit in federal court, including initial considerations and drafting the case initiating civil lawsuit in US district courts and the major documents, see Practice Notes, Commencing a Federal Lawsuit: procedural and practical considerations counsel Initial Considerations (http://us.practicallaw.com/3-504-0061) and Commencing a Federal Lawsuit: Drafting the Complaint (http:// face during a lawsuit's early stages. Specifically, us.practicallaw.com/5-506-8600); see also Standard Document, this Note explains how to begin a lawsuit, Complaint (Federal) (http://us.practicallaw.com/9-507-9951). respond to a complaint, prepare to defend a The plaintiff must include with the complaint: lawsuit and comply with discovery obligations The $400 filing fee. early in the litigation. Two copies of a corporate disclosure statement, if required (FRCP 7.1). A civil cover sheet, if required by the court's local rules. This Note explains the initial steps of a civil lawsuit in US district For more information on filing procedures in federal court, see courts (the trial courts of the federal court system) and the major Practice Note, Commencing a Federal Lawsuit: Filing and Serving the procedural and practical considerations counsel face during a Complaint (http://us.practicallaw.com/9-506-3484). lawsuit's early stages. It covers the steps from filing a complaint through the initial disclosures litigants must make in connection with SERVICE OF PROCESS discovery. -

Retaliatory RICO and the Puzzle of Fraudulent Claiming Nora Freeman Engstrom Stanford Law School

Michigan Law Review Volume 115 | Issue 5 2017 Retaliatory RICO and the Puzzle of Fraudulent Claiming Nora Freeman Engstrom Stanford Law School Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Litigation Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Nora Freeman Engstrom, Retaliatory RICO and the Puzzle of Fraudulent Claiming, 115 Mich. L. Rev. 639 (2017). Available at: http://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol115/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RETALIATORY RICO AND THE PUZZLE OF FRAUDULENT CLAIMING Nora Freeman Engstrom* Over the past century, the allegation that the tort liability system incentivizes legal extortion and is chock-full of fraudulent claims has dominated public discussion and prompted lawmakers to ever-more-creatively curtail individu- als’ incentives and opportunities to seek redress. Unsatisfied with these con- ventional efforts, in recent years, at least a dozen corporate defendants have “discovered” a new fraud-fighting tool. They’ve started filing retaliatory RICO suits against plaintiffs and their lawyers and experts, alleging that the initia- tion of certain nonmeritorious litigation constitutes racketeering activity— while tort reform advocates have applauded these efforts and exhorted more “courageous” companies to follow suit. Curiously, though, all of this has taken place against a virtual empirical void. Is the tort liability system actually brimming with fraudulent claims? No one knows. -

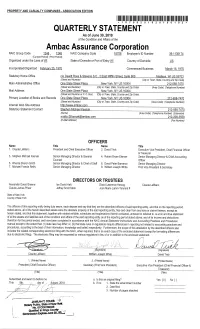

Ambac Assurance Corporation ASSETS Current Statement Date 4 1 2 3 Net Admitted December 31 Nonadmitted Assets Prior Year Net Assets Assets (Cols

PROPERTY AND CASUALTY COMPANIES - ASSOCIATION EDITION 11111 11111 1 11111111 11 II II 11111111 1111111 18 08 11 12 0 1 0 0 1 0 2 * QUARTERLY STATEMENT As of June 30, 2018 of the Condition and Affairs of the Ambac Assurance Corporation NAIC Group Code 1248, 1248 NAIC Company Code 18708 Employer's ID Number 39-1135174 (Current Period) (Prior Period) Organized under the Laws of WI State of Domicile or Port of Entry WI Country of Domicile US Incorporated/Organized February 25, 1970 Commenced Business . March 16, 1970 Statutory Home Office c/o Dewitt Ross & Stevens S.C., 2 East Mifflin Street, Suite 600 Madison, WI US 53703 (Street and Number) (City or Town, State, Country and Zip Code) Main Administrative Office One State Street Plaza New York, NY US 10004 212-658-7470 (Street and Number) (City or Town, State, Country and Zip Code) (Area Code) (Telephone Number) Mail Address One State Street Plaza New York, NY US 10004 (Street and Number or P. 0. Box) (City or Town, State, Country and Zip Code) Primary Location of Books and Records One State Street Plaza New York, NY US 10004 212-658-7470 (Street and Number) (City or Town, State, Country and Zip Code) (Area Code) (Telephone Number) Internet Web Site Address http://www.ambac.com Statutory Statement Contact Stephen Michael Ksenak 212-658-7470 (Name) (Area Code) (Telephone Number) (Extension) mailto:SKsenakQambac.com 212-208-3558 (E-Mail Address) (Fax Number) OFFICERS Name Title Name Title 1 . Claude LeBlanc President and Chief Executive Officer 2. David Trick Executive Vice President, Chief Financial Officer & Treasurer 3.