Lectio Divina & Carmel's Attentiveness to the Bible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCTOBER 2019 No 10

OCTOBER 2019 NO 10 ligious and lai News Re ty th AAof the Assumption e same mission EDITORIAL Happy are those called to the supper of the Lord « For us religious, it is necessary to center our lives on the Word of God. It is crucial that this Word becomes the source of life and renewal. » >> Official Agenda Jubilee of the Province of Africa The Assumptionist Province of Africa celebrates its 50th Plenary General Council anniversary this year: a jubilee celebrated in Butembo • n° 5 : December 2-10, 2019, in Rome. at the end of the month of August. The following is the • n° 6 : June 2-10, 2020, in Worcester (United letter addressed by the Superior General for this occa- States). sion, on August 19, 2019, to Fr. Yves Nzuva Kaghoma, • n° 7 : December 3-11, 2020, in Nîmes Provincial Superior: (France). Dear Brothers of the African Province, Ordinary General Councils • n° 16: November 11-15, 2019. It was 50 years ago, on July 3, 1969, that the Province of • n° 17 : December 11-12, 2019. Africa was founded. Resulting from long missionary work by • n° 18 : February 10-14, 2020. the Assumptionists, the young Province began its process • n° 19 : March 18-19, 2020. of development and the progressive assumption of respon- • n° 20 : April 20-24, 2020. sibility by the indigenous brothers. Today, though the mis- Benoît sionary presence is very limited---too limited in my eyes---, you have yourselves become missionaries. The important • October 1-10: Belgium and the Netherlands. number of religious present to the stranger for pastoral rea- • October 20-November 6: Madagascar. -

Medieval Devotion to Mary Among the Carmelites Eamon R

Marian Studies Volume 52 The Marian Dimension of Christian Article 11 Spirituality, Historical Perspectives, I. The Early Period 2001 The aM rian Spirituality of the Medieval Religious Orders: Medieval Devotion to Mary Among the Carmelites Eamon R. Carroll Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Carroll, Eamon R. (2001) "The aM rian Spirituality of the Medieval Religious Orders: Medieval Devotion to Mary Among the Carmelites," Marian Studies: Vol. 52, Article 11. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol52/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Carroll: Medieval Devotions…Carmelites The Marian Spirituality of the Medieval Religious Orders: Medieval Devotion ... Carmelites MEDIEVAL DEVOTION TO MARY AMONG THE CARMELITES Eamon R. Carroll, 0. Carm. * The word Carmel virtually defines the religious family that calls itself the Carmelite Order. It is a geographical designation (as in also Carthusian and Cistercian), not a person's name like Francis, Dominic and the Servite Seven Holy Founders. In the Church's calendar, Carmel is one of three Marian sites celebrated liturgically, along with Lourdes and St. Mary Major. It may be asked: Who founded the Carmelites on Mount Carmel? There is no easy answer, though some names have been suggested, begin, ning with the letter B-Brocard, Berthold, ...What is known is that during the Crusades in the late eleven,hundreds some Euro, peans settled as hermits on Mount Carmel, in the land where the Savior had lived. -

VOWS in the SECULAR ORDER of DISCALCED CARMELITES Fr

VOWS IN THE SECULAR ORDER OF DISCALCED CARMELITES Fr. Michael Buckley, OCD The moment we hear the word “Vows” we think automatically of religious. The “vows of religion” is a phrase that comes immediately to our minds: vows and religion are always associated in our thinking. Indeed, for religious men and women, vows of poverty, chastity and obedience are of the very essence of their vocation. Regularly vows are made after novitiate, and again a few years later; the only difference is between simple (temporary) and solemn (perpetual) vows. So it is a new concept when we encounter vows in the context of a Secular Order as we do in Carmel. Yet, the exclusive association of vows with religious people is not warranted. A glance at the Canon Law of the Church will illustrate this. The Canon Law speaks about vows in numbers 1191-98, just before a chapter on oaths. Our Secular legislation makes no reference to the Canon Law when it speaks about vows. That is not necessarily a defect or lacuna in our Constitutions. Our legislation is in accord with sacred canons, but it is essential to be familiar with these. Let me summarize the chapter. It begins with a precise definition: “A vow is a deliberate and free promise made to God concerning a possible and better good which must be fulfilled by reason of the virtue of religion.” Then it goes on to distinguish vows which are a) public, i.e., accepted in the name of the church, b) solemn or simple, c) personal or real, d) how vows cease or are dispensed, etc. -

CARMELITES REMEMBER the MISSION Mount Carmel N Honor of Veterans Day, Commit to the Mission

Our Lady of Mount Carmel, Pray for us. Volume 18, Issue 1 May 2011 Published by the Mount Carmel Alumni Foundation CARMELITES REMEMBER THE MISSION Mount Carmel n honor of Veterans Day, commit to The Mission. Alma Mater Carmelite Alumni veterans On peaceful shores from Mt. Carmel High In 1934 the Carmelites began their ‘neath western skies our I hymn of praise we sing, School and Crespi Carmelite Los Angeles mission building High School gathered to watch Mount Carmel High School on To thee our Alma Mater dear, now let our voices the Crespi vs. Loyola football 70th and Hoover. Their mission ring! game and to reminisce and re- was to provide a Catholic college All hail to thee Mount Carmel High, Crusaders Sons are we! We love your ways, your spirit bold! We pledge ourselves to thee! Inside this issue: Carmelites recall the mission . 1,2 The Lady of the Place . 3 Golf Tournament Monday, May 16th 2011. 4,5 Field of Dreams . 6 Who designed the Crusader Picture L-R…Aviators share mission stories… Website. 7 A Haire Affair & Ryan Michael O’Brien MC’41 flew 35 bombing missions over other annoucements . 8 Germany in WWII receiving the Distinguished Flying Cross. Dec. Board Meeting . 9 Lt. Col Kim “Mo” Mahoney USMC CHS’88, pilots F-18’s and is a veteran of three Iraq deployments. Lt. Col. Joe Faherty MC’63 USAF (RET) flew C-130’s in Viet Nam. Continued on Page 2 The purpose of the Mount Carmel Alumni Foundation is to provide financial assistance to the Carmelite Community and to the Catholic elementary schools in South-Central Los Angeles that have provided our alumni with an excellent education. -

Religious Houses/Communities

74 2012 DIOCESE OF SACRAMENTO DIRECTORY R CRUSADE OF THE HOLY SPIRIT (CHSp.) SOCIETY OF JESUS (SJ) Sacred Heart Parish Jesuit Community at Jesuit High School C P.O. Box 430, Susanville, CA 96130 1200 Jacob Lane, Carmichael, CA 95608 M (530) 257-2181, ext. 4382 (916) 482-6060 • Fax (916) 972-8037 Fax (530) 257-6508 St. Ignatius Loyola Parish BROTHERS OF THE CHRISTIAN SCHOOLS (FSC) DOMINICANS - ORDER OF PREACHERS (OP) 3235 Arden Way, Sacramento, CA 95825 Christian Brothers High School 475 East I Street, Benicia (916) 482-9666 • Fax (916) 482-6573 4315 Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd. Mail: P.O. Box 756, Benicia, CA 94510 Newman Catholic Community Sacramento, CA 95820 • (916) 733-3600 (707) 747-7220 • Fax (707) 745-5642 5900 Newman Ct., Sacramento, CA 95819 CARMELITE FATHERS (O. CARM.) FRANCISCANS-ORDER OF FRIARS MINOR (OFM) (916) 480-2198 • Fax (916) 454-4180 698 Berkeley Way, Fair# eld, CA 94533 St. Francis of Assisi Friary VERBUM DEI MISSIONARY FRATERNITY (VDMF) (707) 426-3639 • Fax (707) 422-7946 1112 26th Street, Sacramento, CA 95816 Holy Rosary Parish Pastoral Center, 503 California St., CARMELITES OF MARY IMMACULATE (CMI) (916) 962-0919 • E-mail: [email protected] Woodland, CA 95695 St. Mary Parish (530) 662-2805 • Fax (530) 662-0796 1333 58th St., Sacramento, CA 95819-4240 LEGIONARIES OF CHRIST (LC) (916) 452-0296 Our Lady of Guadalupe Church CISTERCIAN ORDER OF THE STRICT 1909 7th St., Sacramento, CA 95814 OBSERVANCE - TRAPPIST (OCSO) (916) 541-3556 • Fax (916) 442-3679 Abbey of New Clairvaux OBLATES OF ST. JOSEPH (OSJ) 26240 7th Street (P.O. -

1 the New Monasticon Hibernicum and Inquiry Into

THE NEW MONASTICON HIBERNICUM AND INQUIRY INTO THE EARLY CHRISTIAN AND MEDIEVAL CHURCH IN IRELAND Launched in October 2003 under the auspices of the Irish Research Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences, the ‘Monasticon Hibernicum’ project is based in the Department of Old and Middle Irish at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth, Co. Kildare. Central to the project is a database of the native Early Christian and Medieval (5th to 12th centuries AD) ecclesiastical foundations of Ireland - managed by research fellows Ailbhe MacShamhráin and Aidan Breen, under the general direction of Kim McCone, professor of Old and Middle Irish. A longer-term goal is to produce a dictionary of the Early Christian churches, cathedrals, monasteries, convents and hermitages of Ireland for which historical, archaeological or placename evidence survives. The title of the project pays tribute to Mervyn Archdall’s Monasticon Hibernicum; but what is envisaged here goes beyond revision of such antiquarian classics.1 The comprehensive character of this new Monasticon (the database already features a number of sites which are indicated solely by historical, or by archaeological, or placename evidence), along with its structure and referencing, will make for more than a general reference book. It is envisaged as a research-tool to further inquiry in the fields of history (helping to illuminate, for example, ecclesiastico-political relationships, pre-reform church organisation, the dissemination of saints’ cults and gender-politics in the Irish church) and settlement studies - as illustrated below with reference to some of the Leinster data. The first phase of the project, carried out during the academic year 2003-04, has focused on the ecclesiastical province of Dublin – which includes the dioceses of Dublin itself, Glendalough, Ferns, Kildare, Leighlin and Ossory. -

Catholic Women Religious in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Sisterhood on the Frontier: Catholic Women Religious in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850- 1925 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Jamila Jamison Sinlao Committee in charge: Professor Denise Bielby, Chair Professor Jon Cruz Professor Simonetta Falasca-Zamponi Professor John Mohr December 2018 The dissertation of Jamila Jamison Sinlao is approved. Jon Cruz Simonetta Falsca-Zamponi John Mohr Denise Bielby, Committee Chair December 2018 Sisterhood on the Frontier: Catholic Women Religious in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1850- 1925 Copyright © 2018 by Jamila Jamison Sinlao iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In so many ways, this dissertation is a labor of love, shaped by the formative years that I spent as a student at Mercy High School, Burlingame. There, the “Mercy spirit”—one of hospitality and generosity, resilience and faith—was illustrated by the many stories we heard about Catherine McAuley and Mary Baptist Russell. The questions that guide this project grew out of my Mercy experience, and so I would like to thank the many teachers, both lay and religious, who nurtured my interest in this fascinating slice of history. This project would not have been possible without the archivists who not only granted me the privilege to access their collections, but who inspired me with their passion, dedication, and deep historical knowledge. I am indebted to Chris Doan, former archivist for the Sisters of the Presentation of the Blessed Virgin Mary; Sister Marilyn Gouailhardou, RSM, regional community archivist for the Sisters of Mercy Burlingame; Sister Margaret Ann Gainey, DC, archivist for the Daughters of Charity, Seton Provincialate; Kathy O’Connor, archivist for the Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur, California Province; and Sister Michaela O’Connor, SHF, archivist for the Sisters of the Holy Family. -

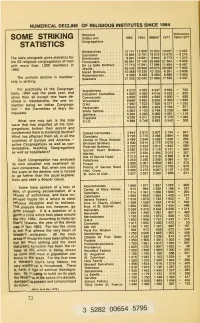

Some Striking

NUMERICAL DECLINE OF RELIGIOUS INSTITUTES SINCE 1964 Religious Difference SOME STRIKING Orders and 1964/1977 STATISTICS Congregations Benedictines 12 131 12 500 12 070 10 037 -2 463 Capuchins 15 849 15 751 15 575 12 475 - 3 276 - The table alongside gives statistics for Dominicans 9 991 10091 9 946 8 773 1 318 the 62 religious congregations of men Franciscans 26 961 27 140 26 666 21 504 -5 636 17584 11 484 - 6 497 . 17 981 with more than 1,000 members in De La Salle Brothers . 17710 - Jesuits 35 438 35 968 35 573 28 038 7 930 1962. - Marist Brothers 10 068 10 230 10 125 6 291 3 939 Redemptorists 9 308 9 450 9 080 6 888 - 2 562 uniform decline in member- - The Salesians 21 355 22 042 21 900 17 535 4 507 ship is striking. practically all the Congrega- For Augustinians 4 273 4 353 4 447 3 650 703 1964 was the peak year, and 3 425 625 tions, . 4 050 Discalced Carmelites . 4 050 4016 since then all except one have de- Conventuals 4 650 4 650 4 590 4000 650 4 333 1 659 clined in membership, the one ex- Vincentians 5 966 5 992 5 900 7 623 7 526 6 271 1 352 ception being an Indian Congrega- O.M.I 7 592 Passionists 3 935 4 065 4 204 3 194 871 tion - the Carmelites of Mary Im- White Fathers 4 083 4 120 3 749 3 235 885 maculate. Spiritans 5 200 5 200 5 060 4 081 1 119 Trappists 4 339 4 211 3819 3 179 1 032 What, one may ask, is this tidal S.V.D 5 588 5 746 5 693 5 243 503 wave that has engulfed all the Con- gregations, broken their ascent and condemned them to statistical decline? Calced Carmelites ... -

Allocutio – July 8, 2012 the Legionary Must Propagate Everything Catholic

Allocutio – July 8, 2012 The Legionary Must Propagate Everything Catholic (Handbook Chapter 39 #34 pgs 305-306) Fr. Richard Soulliere, Spiritual Director In his Allocutio, Fr. Soulliere spoke about the Spiritual Reading. The first item that the Handbook mentions in the section entitled “The Legionary Must Propagate Everything Catholic” (Handbook, p. 305, #34) is the Brown Scapular. After Our Lord died on the cross, many people wanted to visit the Holy Land. They wanted to see Bethlehem where Jesus was born, Nazareth where He lived, and the Garden of Gethsemane and Calvary where He suffered and died. Some were so moved emotionally that they decided to stay there. Of these, some of the men made their way to Mt. Carmel, made famous in the Old Testament by St. Elias. It is northwest of Jerusalem, close by the sea, rising about 1,000 feet, its fertility, beauty and numerous caves making it peculiarly appropriate for hermits. There may have been some descendents of the followers of St. Elijah still living there. As I recall, it does not have a peak, but its top is a broad plateau. As the years passed, these men got to know one another, formed a community and eventually applied to Rome to be accepted as a congregation in the Roman Catholic Church, which was later approved in 1210. The name of the order is the Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mt. Carmel. To the people living in the valleys below, they became known as “the Carmelites” or “those men living on Mt. Carmel.” Over the years they developed two things: (1) a great devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary, and (2) a garment they called the “scapular.” This garment runs, in front, from the knees over the shoulders, with an opening for the head and neck, and down the back to the knee area. -

News Youth Team

RELIGIOUS OF THE ASSUMPTION • ENGLAND 9 March NEWS from the Each of us has “ a mission on earth. It is simply a question YOUTH TEAM of seeking how God can use us to make his in England gospel known and lived.” St Marie-Eugenie The Youth team of the English Territory continues to Members of the team: work together within the new European Province. It remains a place to share ideas, encourage each other and prepare our events together. We - as Assumption Youth and Volunteers - are members of the national Catholic Youth Ministry Federation (CYMFed) - which aims to form and serve Sr Emmanuel Bac Catechesis / pastoral youth ministry in England and Wales. In March, our ministry with the Assumption group joined the biggest Catholic Vietnamese community, Summer Camp national youth gathering organised by CYMFed, the Flame Congress. Read our report inside this edition. Sr Cathy Jones Vocations ministry, For the feast of St Marie-Eugénie three sisters shared retreats and accompaniment to a brief reflection on inspiration of our foundress for young people their life and vocation as religious sisters. If you haven’t seen the short videos yet, check out our YouTube channel: www.bit.ly/rota-uk Sr Carolyn Morrison We would also like to share the information University chaplaincy, gathered about Assumption youth events with social outreach focus, pilgrimages and in Europe this summer - if you know anyone service who might be interested - don’t hesitate to share it! For details, follow the link: Helen Granger Coordinator of the www.bit.ly/ra-summer Assumption Volunteers Programme in the UK Anne Marie Salgo Assumption youth & education, communication www.assumptionreligious.org [email protected] @AssumptionRA facebook.com/ assumptionUK Young people and religious from 5 congregations gathered in Milleret House for a vocations retreat day. -

Books Recommended for Ongoing Formation

BOOKS RECOMMENDED FOR ONGOING FORMATION **indicates that the book is available for purchase from the Lay Carmelite Office **A Pattern for Live, The Rule of St. Albert and the Carmelite Laity, by Patrick McMahon, O.Carm. In this book the author presents a powerful defense of the suitability of Albert’s Rule (pattern for life_ for all Carmelites — laity and religious alike. In both setting an historical context for the Rule and providing a practical commentary for the laity, Fr. Patrick demonstrates that it is adherence to the Rule that defines a Carmelite and gives each of us our Carmelite identity. The Ascent to Joy: John of the Cross, Selected Spiritual Writings, (Marc Foley, OCD, editor) New City Press, 2002 In this introduction and anthology, the author leads the reader step-by-step into the very heart of the spiritual way taught by John of the Cross. He provides substantial introductions and notes, but the core of the teaching is developed in carefully selected excerpts from John’s writings, presented in a systematic order, so the text functions both as a primer of John’s teaching and an introduction to the contemplative way. (The) Ascent of Mt. Carmel: Reflections, St. John of the Cross (Marc Foley, OCD) ICS Publications, 2013 The author weaves together insights from psychology, theology, and great literature to make The Ascent of Mt. Carmel both understandable and relevant to daily life. Through his explanations and examples, Fr. Foley “translates” spiritual issues of John’s day to fit the experience of 21st century pilgrims. **At the Fountain of Elijah, by Wilfrid McGreal, O.Carm., Orbis Press Overview of Carmelite Spirituality Awakening Your Soul to the Presence of God, by Kilian Healy, O.Carm., Sophia Institute Press (about living in God’s presence) **Book of the First Monks, by Felip Ribot, O.Carm. -

Elder Sophrony

Saint Tikhon’s Orthodox Theological Seminary Elder Sophrony The Grace of Godforsakenness & The Dark Night of the Soul By Presbyter Mikel Hill A thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Divinity South Canaan, Pennsylvania 2017 Elder Sophrony: The Grace of Godforsakenness & The Dark Night of the Soul by Presbyter Mikel Hill A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF DIVINITY 2017 Approved by Date Faculty Mentor: Dr. Christopher Veniamin Approved by Date Second Reader: Very Rev. David Hester Approved by Date Academic Dean: Very Rev. Steven Voytovich Saint Tikhon’s Orthodox Theological Seminary Abstract By Presbyter Mikel Hill Faculty Mentor: Professor Christopher Veniamin, Department of Patristics The purpose of this thesis is to compare the experience of Godforsakenness, described by Elder Sophrony (+1993), and the Dark Night in the writings of the 16th century Carmelite monk, John of the Cross (1542-1591). Hieromonk Nicholas (Sakharov), in his study of Elder Sophrony I Love Therefore I Am, suggests such a comparison and this suggestion forms the impetus for the greater exploration conducted within the present thesis. Elder Sophrony represents one of the most articulate voices of the Orthodox Patristic tradition in our present times. Elder Sophrony speaks from his own experience of Godforsakenness with eyes transformed by his vision of Christ in Glory. Likewise, John of the Cross bases his teachings on the Dark Night largely on his own experience, but framed within a tradition quite different from Elder Sophrony. John of the Cross represents a long line of medieval Mystics, including Meister Eckhert and Francisco de Osuna, who were shaped largely by their late medieval interpretation of Aristotle, Augustine and Dionysius.