Hiv Drug Resistance: Problems and Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterization of Resistance to a Potent D-Peptide HIV Entry Inhibitor

Smith et al. Retrovirology (2019) 16:28 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12977-019-0489-7 Retrovirology RESEARCH Open Access Characterization of resistance to a potent D-peptide HIV entry inhibitor Amanda R. Smith1†, Matthew T. Weinstock1†, Amanda E. Siglin2, Frank G. Whitby1, J. Nicholas Francis1, Christopher P. Hill1, Debra M. Eckert1, Michael J. Root2 and Michael S. Kay1* Abstract Background: PIE12-trimer is a highly potent D-peptide HIV-1 entry inhibitor that broadly targets group M isolates. It specifcally binds the three identical conserved hydrophobic pockets at the base of the gp41 N-trimer with sub- femtomolar afnity. This extremely high afnity for the transiently exposed gp41 trimer provides a reserve of binding energy (resistance capacitor) to prevent the viral resistance pathway of stepwise accumulation of modest afnity- disrupting mutations. Such modest mutations would not afect PIE12-trimer potency and therefore not confer a selective advantage. Viral passaging in the presence of escalating PIE12-trimer concentrations ultimately selected for PIE12-trimer resistant populations, but required an extremely extended timeframe (> 1 year) in comparison to other entry inhibitors. Eventually, HIV developed resistance to PIE12-trimer by mutating Q577 in the gp41 pocket. Results: Using deep sequence analysis, we identifed three mutations at Q577 (R, N and K) in our two PIE12-trimer resistant pools. Each point mutant is capable of conferring the majority of PIE12-trimer resistance seen in the poly- clonal pools. Surface plasmon resonance studies demonstrated substantial afnity loss between PIE12-trimer and the Q577R-mutated gp41 pocket. A high-resolution X-ray crystal structure of PIE12 bound to the Q577R pocket revealed the loss of two hydrogen bonds, the repositioning of neighboring residues, and a small decrease in buried surface area. -

HIV DRUG RESISTANCE EARLY WARNING INDICATORS World Health Organization Indicators to Monitor HIV Drug Resistance Prevention at Antiretroviral Treatment Sites

HIV DRUG RESISTANCE EARLY WARNING INDICATORS World Health Organization indicators to monitor HIV drug resistance prevention at antiretroviral treatment sites June 2010 Update ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The preparation of this document would not have been possible without the participation and assistance of many experts. Their work helped us to define HIV Drug Resistance Early Warning Indicators and to put together this guidance document. The World Health Organization wishes to acknowledge comments and contributions of the following individuals on the original guidance document, published in 2008: John Aberle-Grasse (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA) David Bangsberg University of California-San Francisco, USA), George Bello (Ministry of Health, Malawi), Andrea De Luca (Università Cattolica of Rome, Italy), Caroline Fonck (WHO Haiti), Guy-Michel Gershy-Damet (WHO Africa Regional Office/Inter- Country Support Team, Burkina Faso), Bethany Hedt (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Malawi), Michael Jordan (Tufts University School of Medicine, USA) , Sidibe Kassim (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA), Velephi Okello (Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Swaziland), Padmini Srikantiah (WHO South East Asia Regional Office), Zeenat Patel (WHO Western Pacific Regional Office), and Nellie Wadonda-Kabondo (Ministry of Health, Malawi). Dongbao Yu (WHO Western Pacific Regional Office) provided input on the 2010 update. The original work was coordinated by Diane Bennett, Silvia Bertagnolio, Giovanni Ravasi (WHO/HTM/HIV, Geneva, -

HIV Genotyping and Phenotyping AHS – M2093

Corporate Medical Policy HIV Genotyping and Phenotyping AHS – M2093 File Name: HIV_genotyping_and_phenotyping Origination: 1/2019 Last CAP Review: 2/2021 Next CAP Review: 2/2022 Last Review: 2/2021 Description of Procedure or Service Description Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an RNA retrovirus that infects human immune cells (specifically CD4 cells) causing progressive deterioration of the immune system ultimately leading to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) characterized by susceptibility to opportunistic infections and HIV-related cancers (CDC, 2014). Related Policies Plasma HIV-1 and HIV-2 RNA Quantification for HIV Infection Scientific Background Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) targets the immune system, eventually hindering the body’s ability to fight infections and diseases. If not treated, an HIV infection may lead to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) which is a condition caused by the virus. There are two main types of HIV: HIV-1 and HIV-2; both are genetically different. HIV-1 is more common and widespread than HIV-2. HIV replicates rapidly; a replication cycle rate of approximately one to two days ensures that after a single year, the virus in an infected individual may be 200 to 300 generations removed from the initial infection-causing virus (Coffin & Swanstrom, 2013). This leads to great genetic diversity of each HIV infection in a single individual. As an RNA retrovirus, HIV requires the use of a reverse transcriptase for replication purposes. A reverse transcriptase is an enzyme which generates complimentary DNA from an RNA template. This enzyme is error-prone with the overall single-step point mutation rate reaching ∼3.4 × 10−5 mutations per base per replication cycle (Mansky & Temin, 1995), leading to approximately one genome in three containing a mutation after each round of replication (some of which confer drug resistance). -

Summary of Neuraminidase Amino Acid Substitutions Associated with Reduced Inhibition by Neuraminidase Inhibitors

Summary of neuraminidase amino acid substitutions associated with reduced inhibition by neuraminidase inhibitors. Susceptibility assessed by NA inhibition assays Source of Type/subtype Amino acid N2 b (IC50 fold change vs wild type [NAI susceptible virus]) viruses/ References Comments substitutiona numberinga Oseltamivir Zanamivir Peramivir Laninamivir selection withc A(H1N1)pdm09 I117R 117 NI (1) RI (10) ? ?d Sur (1) E119A 119 NI/RI (8-17) RI (58-90) NI/RI (7-12) RI (82) RG (2, 3) E119D 119 RI (25-23) HRI (583-827) HRI (104-286) HRI (702) Clin/Zan; RG (3, 4) E119G 119 NI (1-7) HRI (113-1306) RI/HRI (51-167) HRI (327) RG; Clin/Zan (3, 5, 6) E119V 119 RI (60) HRI (571) RI (25) ? RG (5) Q136K/Q 136 NI (1) RI (20) ? ? Sur (1) Q136K 136 NI (1) HRI (86-749) HRI (143) RI (42-45) Sur; RG; in vitro (2, 7, 8) Q136R was host Q136R 136 NI (1) HRI (200) HRI (234) RI (33) Sur (9) cell selected D151D/E 151 NI (3) RI (19) RI (14) NI (5) Sur (9) D151N/D 151 RI (22) RI (21) NI (3) NI (3) Sur (1) R152K 152 RI(18) NI(4) NI(4) ? RG (3, 6) D199E 198 RI (16) NI (7) ? ? Sur (10) D199G 198 RI (17) NI (6) NI (2) NI (2) Sur; in vitro; RG (2, 5) I223K 222 RI (12–39) NI (5–6) NI (1–4) NI (4) Sur; RG (10-12) Clin/No; I223R 222 RI (13–45) NI/RI (8–12) NI (5) NI (2) (10, 12-15) Clin/Ose/Zan; RG I223V 222 NI (6) NI (2) NI (2) NI (1) RG (2, 5) I223T 222 NI/RI(9-15) NI(3) NI(2) NI(2) Clin/Sur (2) S247N 246 NI (4–8) NI (2–5) NI (1) ? Sur (16) S247G 246 RI (15) NI (1) NI (1) NI (1) Clin/Sur (10) S247R 246 RI (36-37) RI (51-54) RI/HRI (94-115) RI/HRI (90-122) Clin/No (1) -

Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescent Living With

Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV Developed by the DHHS Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents – A Working Group of the Office of AIDS Research Advisory Council (OARAC) How to Cite the Adult and Adolescent Guidelines: Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/ AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed [insert date] [insert page number, table number, etc. if applicable] It is emphasized that concepts relevant to HIV management evolve rapidly. The Panel has a mechanism to update recommendations on a regular basis, and the most recent information is available on the HIVinfo Web site (http://hivinfo.nih.gov). What’s New in the Guidelines? August 16, 2021 Hepatitis C Virus/HIV Coinfection • Table 18 of this section has been updated to include recommendations regarding concomitant use of fostemsavir or long acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine with different hepatitis C treatment regimens. June 3, 2021 What to Start • Since the release of the last guidelines, updated data from the Botswana Tsepamo study have shown that the prevalence of neural tube defects (NTD) associated with dolutegravir (DTG) use during conception is much lower than previously reported. Based on these new data, the Panel now recommends that a DTG-based regimen can be prescribed for most people with HIV who are of childbearing potential. Before initiating a DTG-based regimen, clinicians should discuss the risks and benefits of using DTG with persons of childbearing potential, to allow them to make an informed decision. -

HIV-1 Protease: Structural Perspectives on Drug Resistance

Viruses 2009, 1, 1110-1136; doi:10.3390/v1031110 OPEN ACCESS viruses ISSN 1999-4915 www.mdpi.com/journal/viruses Review HIV-1 Protease: Structural Perspectives on Drug Resistance Irene T. Weber * and Johnson Agniswamy Department of Biology, Molecular Basis of Disease Program, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA 30303, USA; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-404-413-5411; Fax: +1-404-413-5301. Received: 1 October 2009; in revised form: 30 November 2009 / Accepted: 1 December 2009 / Published: 3 December 2009 Abstract: Antiviral inhibitors of HIV-1 protease are a notable success of structure-based drug design and have dramatically improved AIDS therapy. Analysis of the structures and activities of drug resistant protease variants has revealed novel molecular mechanisms of drug resistance and guided the design of tight-binding inhibitors for resistant variants. The plethora of structures reveals distinct molecular mechanisms associated with resistance: mutations that alter the protease interactions with inhibitors or substrates; mutations that alter dimer stability; and distal mutations that transmit changes to the active site. These insights will inform the continuing design of novel antiviral inhibitors targeting resistant strains of HIV. Keywords: protease inhibitors; drug resistance; aspartic protease; molecular mechanism; darunavir 1. Introduction The structures and activities of HIV protease and its drug-resistant variants and their interactions with inhibitors have been studied for nearly 20 years in order to combat the challenges of AIDS antiviral therapy and the evolution of HIV drug resistance [1]. About 25 different antiretroviral drugs (ARV) are currently used in the combat against human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). -

Emergence of HIV-1 Drug Resistance Mutations in Mothers on Treatment

Martin-Odoom et al. Virology Journal (2018) 15:143 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-018-1051-2 RESEARCH Open Access Emergence of HIV-1 drug resistance mutations in mothers on treatment with a history of prophylaxis in Ghana Alexander Martin-Odoom1* , Charles Addoquaye Brown1, John Kofi Odoom2, Evelyn Yayra Bonney2, Nana Afia Asante Ntim2, Elena Delgado3, Margaret Lartey4, Kwamena William Sagoe1, Theophilus Adiku1 and William Kwabena Ampofo2 Abstract Background: Antiretrovirals have been available in Ghana since 2003 for HIV-1 positive pregnant women for prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT). Suboptimal responses to treatment observed post-PMTCT interventions necessitated the need to investigate the profile of viral mutations generated. This study investigated HIV-1 drug resistance profiles in mothers in selected centres in Ghana on treatment with a history of prophylaxis. Methods: Genotypic Drug Resistance Testing for HIV-1 was carried out. Subtyping was done by phylogenetic analysis and Stanford HIV Database programme was used for drug resistance analysis and interpretation. To compare the significance between the different groups and the emergence of drug resistance mutations, p values were used. Results: Participants who had prophylaxis before treatment, those who had treatment without prophylaxis and those yet to initiate PMTCT showed 32% (8), 5% (3) and 15% (4) HIV-1 drug resistance associated mutations respectively. The differences were significant with p value < 0.05. Resistance Associated Mutations (RAMs) were seen in 14 participants (35%) to nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs). The most common NRTI mutation found was M184 V; K103 N and A98G were the most common NNRTI mutations seen. -

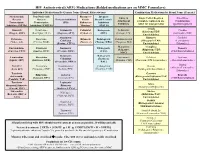

HIV Antiretroviral (ARV) Medications (Bolded Medications Are on MMC

HIV Antiretroviral (ARV) Medications (Bolded medications are on MMC Formulary) Individual Medications By Generic Name (Brand, Abbreviation) Combination Medications by Brand Name (Generic) Nucleos(t)ide Non-Nucleoside Pharmaco- Integrase Entry & Single Tablet Regimen Fixed Dose Reverse Reverse Protease Inhibitors kinetic Strand Transfer Attachment (complete regimen in one Combination Transcriptase Transcriptase (PIs) Enhancers Inhibitors Inhibitors tablet for most patients) (partial regimen) Inhibitors (NRTIs) Inhibitors (NNRTIs) “Boosters” (INSTIs) Atripla Abacavir Delavirdine Atazanavir Cobicistat Bictegravir Enfuvirtide Cimduo (Efavirenz/TDF/ (Ziagen, ABC) (Rescriptor, DLV) (Reyataz, ATV) (Tybost, c) (BIC) (Fuzeon, T20) (Lamivudine/TDF) Emtricitabine) Atazanavir/ Biktarvy Combivir Didanosine Doravirine Ritonavir Dolutegravir Ibalizumab-uiyk Cobicistat (Bictegravir/TAF/ (Lamivudine/ (Videx, ddl) (Pifeltro, DOR) (Norvir, r) (Tivicay, DTG) (Trogarzo, IBA) (Evotaz, ATV/c) Emtricitabine) Zidovudine) Maraviroc Complera Emtricitabine Efavirenz Darunavir Elvitegravir Descovy (Selzentry, (Rilpivirine/TDF/ (Emtriva, FTC) (Sustiva, EFV) (Prezista, DRV) (EVG) (TAF/Emtricitabine) MVC) Emtricitabine) Darunavir/ Raltegravir Lamivudine Etravirine Fostemsavir Delstrigo Epzicom Cobisistat (Isentress, (Epivir, 3TC) (Intelence, ETR) (Rukobia, FTR) (Doravirine/TDF/Lamivudine) (Abacavir/Lamivudine) (Prezcobix, DRV/c) RAL) Trizivir Stavudine Nevirapine Fosamprenavir Cabotegravir Dovato (Abacavir/Lamivudine/ (Viramune, NVP) (Lexiva, FPV) (Vocabria, CAB) (Dolutegravir/Lamivudine) -

Superinfection with Drug-Resistant HIV Is Rare and Does Not Contribute

Bartha et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2013, 13:537 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/13/537 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Superinfection with drug-resistant HIV is rare and does not contribute substantially to therapy failure in a large European cohort István Bartha1,2,3,4, Matthias Assel5, Peter MA Sloot6, Maurizio Zazzi7,CarloTorti8,9, Eugen Schülter10, Andrea De Luca11,12, Anders Sönnerborg13, Ana B Abecasis14, Kristel Van Laethem15, Andrea Rosi7, Jenny Svärd13, Roger Paredes16, David AMC van de Vijver17, Anne-Mieke Vandamme15,14 and Viktor Müller1,18* Abstract Background: Superinfection with drug resistant HIV strains could potentially contribute to compromised therapy in patients initially infected with drug-sensitive virus and receiving antiretroviral therapy. To investigate the importance of this potential route to drug resistance, we developed a bioinformatics pipeline to detect superinfection from routinely collected genotyping data, and assessed whether superinfection contributed to increased drug resistance in a large European cohort of viremic, drug treated patients. Methods: We used sequence data from routine genotypic tests spanning the protease and partial reverse transcriptase regions in the Virolab and EuResist databases that collated data from five European countries. Superinfection was indicated when sequences of a patient failed to cluster together in phylogenetic trees constructed with selected sets of control sequences. A subset of the indicated cases was validated by re-sequencing pol and env regions from the original samples. Results: 4425 patients had at least two sequences in the database, with a total of 13816 distinct sequence entries (of which 86% belonged to subtype B). We identified 107 patients with phylogenetic evidence for superinfection. -

Drug Resistance Mutations in HIV-1 Volume 11 Issue 6 November/December 2003

Special Contribution - Drug Resistance Mutations in HIV-1 Volume 11 Issue 6 November/December 2003 Drug Resistance Mutations in HIV-1 Victoria A. Johnson, MD, Françoise Brun-Vézinet, MD, PhD, Bonaventura Clotet, MD, PhD, Brian Conway, MD, Richard T. D'Aquila, MD, Lisa M. Demeter, MD, Daniel R. Kuritzkes, MD, Deenan Pillay, MD, PhD, Jonathan M. Schapiro, MD, Amalio Telenti, MD, PhD, and Douglas D. Richman, MD The International AIDS Society–USA pressure), resistant strains may be pre- V32I and the I84A/C have been added to (IAS–USA) Drug Resistance Mutations sent at levels below the limit of detec- the list of accumulated mutations con- Group is a volunteer panel of experts tion of the test; analyzing stored sam- ferring multi-PI resistance (see User that meets regularly to review and inter- ples (collected under selection pressure) Note 9).13-18 In addition, mutations have pret new data on HIV-1 resistance. The could be useful in this setting; and (3) been added for tipranavir/ritonavir, focus of the group is to identify muta- recognizing that virologic failure of the which is currently available through an tions associated with clinical resistance first regimen typically involves HIV-1 expanded access protocol and is not to HIV-1. These mutations have been isolates with resistance to only 1 or 2 of approved for use by the US FDA. A num- identified by 1 or more of the following the drugs in the regimen; in this setting, ber of major (L33I/F/V, V82L/T, I84V, and criteria: (1) in vitro passage experiments resistance most commonly develops -

Section Only

Antiretroviral Drug Resistance and Resistance Testing in Pregnancy (Last updated December 29, 2020; last reviewed December 29, 2020) Panel’s Recommendations • HIV drug-resistance testing (genotypic and, if indicated, phenotypic) should be performed in women living with HIV whose HIV RNA levels are above the threshold for resistance testing (i.e., >500 to 1,000 copies/mL) before: • Initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) in antiretroviral (ARV)-naive pregnant women who have not been previously tested for ARV resistance (AII), • Initiating ART in ARV-experienced pregnant women (including those who have received pre-exposure prophylaxis) (AIII), or • Modifying ARV regimens for women who are newly pregnant and receiving ARV drugs or who have suboptimal virologic response to the ARV drugs started during pregnancy (AII). • Phenotypic resistance testing is indicated for treatment-experienced persons on failing regimens who are thought to have multidrug resistance (BIII). • ART should be initiated in pregnant women prior to receiving results of ARV-resistance testing; ART should be modified, if necessary, based on the results of resistance assays (BIII). • If the use of an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) is being considered and INSTI resistance is a concern, providers should supplement standard resistance testing with a specific INSTI genotypic resistance assay (BIII). INSTI resistance may be a concern if: • A patient received prior treatment that included an INSTI, or • A patient has a history with a sexual partner on INSTI therapy. • Documented zidovudine (ZDV) resistance does not affect the indications for use of intrapartum intravenous ZDV (see Intrapartum Care for Women with HIV)(BIII). • Choice of ARV regimen for an infant born to a woman with known or suspected drug resistance should be determined in consultation with a pediatric HIV specialist, preferably before delivery (see Antiretroviral Management of Newborns with Perinatal HIV Exposure or HIV Infection) (AIII). -

Improving Viral Protease Inhibitors to Counter Drug Resistance

HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Trends Microbiol Manuscript Author . Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2017 July 01. Published in final edited form as: Trends Microbiol. 2016 July ; 24(7): 547–557. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.010. Improving Viral Protease Inhibitors to Counter Drug Resistance Nese Kurt Yilmaz1, Ronald Swanstrom2, and Celia A. Schiffer1,* 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Pharmacology, University of Massachusetts Medical School, 364 Plantation Street, Worcester, MA 01605, USA 2Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, and the UNC Center for AIDS Research, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, USA Abstract Drug resistance is a major problem in health care, undermining therapy outcomes and necessitating novel approaches to drug design. Extensive studies on resistance to viral protease inhibitors, particularly those of HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus (HCV) protease, revealed a plethora of information on the structural and molecular mechanisms underlying resistance. These insights led to several strategies to improve viral protease inhibitors to counter resistance, such as exploiting the essential biological function and leveraging evolutionary constraints. Incorporation of these strategies into structure-based drug design can minimize vulnerability to resistance, not only for viral proteases but for other quickly evolving drug targets as well, toward designing inhibitors one step ahead of evolution to counter resistance with more intelligent and rational design. Keywords drug resistance; protease inhibitors; HIV-1 protease; substrate envelope; structure based drug design; resistance mutations Drug Resistance and Viral Proteases as Drug Targets Drug resistance is a major health burden in a wide range of diseases from cancer to bacterial and viral infections, causing treatment failure as well as severe economic impact on the healthcare system.