AVT Figure Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HIV DRUG RESISTANCE EARLY WARNING INDICATORS World Health Organization Indicators to Monitor HIV Drug Resistance Prevention at Antiretroviral Treatment Sites

HIV DRUG RESISTANCE EARLY WARNING INDICATORS World Health Organization indicators to monitor HIV drug resistance prevention at antiretroviral treatment sites June 2010 Update ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The preparation of this document would not have been possible without the participation and assistance of many experts. Their work helped us to define HIV Drug Resistance Early Warning Indicators and to put together this guidance document. The World Health Organization wishes to acknowledge comments and contributions of the following individuals on the original guidance document, published in 2008: John Aberle-Grasse (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA) David Bangsberg University of California-San Francisco, USA), George Bello (Ministry of Health, Malawi), Andrea De Luca (Università Cattolica of Rome, Italy), Caroline Fonck (WHO Haiti), Guy-Michel Gershy-Damet (WHO Africa Regional Office/Inter- Country Support Team, Burkina Faso), Bethany Hedt (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Malawi), Michael Jordan (Tufts University School of Medicine, USA) , Sidibe Kassim (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA), Velephi Okello (Ministry of Health and Social Welfare, Swaziland), Padmini Srikantiah (WHO South East Asia Regional Office), Zeenat Patel (WHO Western Pacific Regional Office), and Nellie Wadonda-Kabondo (Ministry of Health, Malawi). Dongbao Yu (WHO Western Pacific Regional Office) provided input on the 2010 update. The original work was coordinated by Diane Bennett, Silvia Bertagnolio, Giovanni Ravasi (WHO/HTM/HIV, Geneva, -

HIV Genotyping and Phenotyping AHS – M2093

Corporate Medical Policy HIV Genotyping and Phenotyping AHS – M2093 File Name: HIV_genotyping_and_phenotyping Origination: 1/2019 Last CAP Review: 2/2021 Next CAP Review: 2/2022 Last Review: 2/2021 Description of Procedure or Service Description Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an RNA retrovirus that infects human immune cells (specifically CD4 cells) causing progressive deterioration of the immune system ultimately leading to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) characterized by susceptibility to opportunistic infections and HIV-related cancers (CDC, 2014). Related Policies Plasma HIV-1 and HIV-2 RNA Quantification for HIV Infection Scientific Background Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) targets the immune system, eventually hindering the body’s ability to fight infections and diseases. If not treated, an HIV infection may lead to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) which is a condition caused by the virus. There are two main types of HIV: HIV-1 and HIV-2; both are genetically different. HIV-1 is more common and widespread than HIV-2. HIV replicates rapidly; a replication cycle rate of approximately one to two days ensures that after a single year, the virus in an infected individual may be 200 to 300 generations removed from the initial infection-causing virus (Coffin & Swanstrom, 2013). This leads to great genetic diversity of each HIV infection in a single individual. As an RNA retrovirus, HIV requires the use of a reverse transcriptase for replication purposes. A reverse transcriptase is an enzyme which generates complimentary DNA from an RNA template. This enzyme is error-prone with the overall single-step point mutation rate reaching ∼3.4 × 10−5 mutations per base per replication cycle (Mansky & Temin, 1995), leading to approximately one genome in three containing a mutation after each round of replication (some of which confer drug resistance). -

Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescent Living With

Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV Developed by the DHHS Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents – A Working Group of the Office of AIDS Research Advisory Council (OARAC) How to Cite the Adult and Adolescent Guidelines: Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents with HIV. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/sites/default/files/guidelines/documents/ AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed [insert date] [insert page number, table number, etc. if applicable] It is emphasized that concepts relevant to HIV management evolve rapidly. The Panel has a mechanism to update recommendations on a regular basis, and the most recent information is available on the HIVinfo Web site (http://hivinfo.nih.gov). What’s New in the Guidelines? August 16, 2021 Hepatitis C Virus/HIV Coinfection • Table 18 of this section has been updated to include recommendations regarding concomitant use of fostemsavir or long acting cabotegravir plus rilpivirine with different hepatitis C treatment regimens. June 3, 2021 What to Start • Since the release of the last guidelines, updated data from the Botswana Tsepamo study have shown that the prevalence of neural tube defects (NTD) associated with dolutegravir (DTG) use during conception is much lower than previously reported. Based on these new data, the Panel now recommends that a DTG-based regimen can be prescribed for most people with HIV who are of childbearing potential. Before initiating a DTG-based regimen, clinicians should discuss the risks and benefits of using DTG with persons of childbearing potential, to allow them to make an informed decision. -

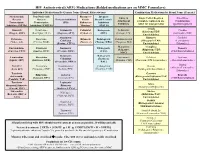

HIV Antiretroviral (ARV) Medications (Bolded Medications Are on MMC

HIV Antiretroviral (ARV) Medications (Bolded medications are on MMC Formulary) Individual Medications By Generic Name (Brand, Abbreviation) Combination Medications by Brand Name (Generic) Nucleos(t)ide Non-Nucleoside Pharmaco- Integrase Entry & Single Tablet Regimen Fixed Dose Reverse Reverse Protease Inhibitors kinetic Strand Transfer Attachment (complete regimen in one Combination Transcriptase Transcriptase (PIs) Enhancers Inhibitors Inhibitors tablet for most patients) (partial regimen) Inhibitors (NRTIs) Inhibitors (NNRTIs) “Boosters” (INSTIs) Atripla Abacavir Delavirdine Atazanavir Cobicistat Bictegravir Enfuvirtide Cimduo (Efavirenz/TDF/ (Ziagen, ABC) (Rescriptor, DLV) (Reyataz, ATV) (Tybost, c) (BIC) (Fuzeon, T20) (Lamivudine/TDF) Emtricitabine) Atazanavir/ Biktarvy Combivir Didanosine Doravirine Ritonavir Dolutegravir Ibalizumab-uiyk Cobicistat (Bictegravir/TAF/ (Lamivudine/ (Videx, ddl) (Pifeltro, DOR) (Norvir, r) (Tivicay, DTG) (Trogarzo, IBA) (Evotaz, ATV/c) Emtricitabine) Zidovudine) Maraviroc Complera Emtricitabine Efavirenz Darunavir Elvitegravir Descovy (Selzentry, (Rilpivirine/TDF/ (Emtriva, FTC) (Sustiva, EFV) (Prezista, DRV) (EVG) (TAF/Emtricitabine) MVC) Emtricitabine) Darunavir/ Raltegravir Lamivudine Etravirine Fostemsavir Delstrigo Epzicom Cobisistat (Isentress, (Epivir, 3TC) (Intelence, ETR) (Rukobia, FTR) (Doravirine/TDF/Lamivudine) (Abacavir/Lamivudine) (Prezcobix, DRV/c) RAL) Trizivir Stavudine Nevirapine Fosamprenavir Cabotegravir Dovato (Abacavir/Lamivudine/ (Viramune, NVP) (Lexiva, FPV) (Vocabria, CAB) (Dolutegravir/Lamivudine) -

Superinfection with Drug-Resistant HIV Is Rare and Does Not Contribute

Bartha et al. BMC Infectious Diseases 2013, 13:537 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/13/537 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Superinfection with drug-resistant HIV is rare and does not contribute substantially to therapy failure in a large European cohort István Bartha1,2,3,4, Matthias Assel5, Peter MA Sloot6, Maurizio Zazzi7,CarloTorti8,9, Eugen Schülter10, Andrea De Luca11,12, Anders Sönnerborg13, Ana B Abecasis14, Kristel Van Laethem15, Andrea Rosi7, Jenny Svärd13, Roger Paredes16, David AMC van de Vijver17, Anne-Mieke Vandamme15,14 and Viktor Müller1,18* Abstract Background: Superinfection with drug resistant HIV strains could potentially contribute to compromised therapy in patients initially infected with drug-sensitive virus and receiving antiretroviral therapy. To investigate the importance of this potential route to drug resistance, we developed a bioinformatics pipeline to detect superinfection from routinely collected genotyping data, and assessed whether superinfection contributed to increased drug resistance in a large European cohort of viremic, drug treated patients. Methods: We used sequence data from routine genotypic tests spanning the protease and partial reverse transcriptase regions in the Virolab and EuResist databases that collated data from five European countries. Superinfection was indicated when sequences of a patient failed to cluster together in phylogenetic trees constructed with selected sets of control sequences. A subset of the indicated cases was validated by re-sequencing pol and env regions from the original samples. Results: 4425 patients had at least two sequences in the database, with a total of 13816 distinct sequence entries (of which 86% belonged to subtype B). We identified 107 patients with phylogenetic evidence for superinfection. -

Section Only

Antiretroviral Drug Resistance and Resistance Testing in Pregnancy (Last updated December 29, 2020; last reviewed December 29, 2020) Panel’s Recommendations • HIV drug-resistance testing (genotypic and, if indicated, phenotypic) should be performed in women living with HIV whose HIV RNA levels are above the threshold for resistance testing (i.e., >500 to 1,000 copies/mL) before: • Initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) in antiretroviral (ARV)-naive pregnant women who have not been previously tested for ARV resistance (AII), • Initiating ART in ARV-experienced pregnant women (including those who have received pre-exposure prophylaxis) (AIII), or • Modifying ARV regimens for women who are newly pregnant and receiving ARV drugs or who have suboptimal virologic response to the ARV drugs started during pregnancy (AII). • Phenotypic resistance testing is indicated for treatment-experienced persons on failing regimens who are thought to have multidrug resistance (BIII). • ART should be initiated in pregnant women prior to receiving results of ARV-resistance testing; ART should be modified, if necessary, based on the results of resistance assays (BIII). • If the use of an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) is being considered and INSTI resistance is a concern, providers should supplement standard resistance testing with a specific INSTI genotypic resistance assay (BIII). INSTI resistance may be a concern if: • A patient received prior treatment that included an INSTI, or • A patient has a history with a sexual partner on INSTI therapy. • Documented zidovudine (ZDV) resistance does not affect the indications for use of intrapartum intravenous ZDV (see Intrapartum Care for Women with HIV)(BIII). • Choice of ARV regimen for an infant born to a woman with known or suspected drug resistance should be determined in consultation with a pediatric HIV specialist, preferably before delivery (see Antiretroviral Management of Newborns with Perinatal HIV Exposure or HIV Infection) (AIII). -

Hiv Drug Resistance: Problems and Perspectives

Title: HIV DRUG RESISTANCE: PROBLEMS AND PERSPECTIVES Author: Pleuni S Pennings Affiliation: Stanford University Running title: HIV DRUG RESISTANCE REVIEW Submitted to: Infectious Disease Reports http://www.pagepress.org/journals/index.php/idr/index Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Daniel Rosenbloom, Alison Hill, Stefany Moreno, Jonathan Li and Nandita Garud for useful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. Version: Jan 20th 2013 Corresponding author: Pleuni Pennings, email: [email protected] OR [email protected] address: Department of Biology 371 Serra St. Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-5020 Keywords: HIV, drug resistance, resistance, antiviral therapy, ART Authors' contributions: PSP wrote the paper Conflicts of interest: there are no conflicts of interest HIV DRUG RESISTANCE: PROBLEMS AND PERSPECTIVES Abstract Access to combination antiretroviral treatment (ART) has improved greatly over recent years. At the end of 2011, more than eight million HIV infected people were receiving antiretroviral therapy in low-income and middle-income countries. ART generally works well in keeping the virus suppressed and the patient healthy. However, treatment only works as long as the virus is not resistant against the drugs used. In the last decades, HIV treatments have become better and better at slowing down the evolution of drug resistance, so that some patients are treated for many years without having any resistance problems. However, for some patients, especially in low-income countries, drug resistance is still a serious threat to their health. This essay will review what is known about transmitted and acquired drug resistance, multi-class drug resistance, resistance to newer drugs, resistance due to treatment for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission, the role of minority variants (low-frequency drug-resistance mutations), and resistance due to pre-exposure prophylaxis. -

Factors Influencing HIV Drug Resistance Among Pregnant Women in Luanda, Angola: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Communication Factors Influencing HIV Drug Resistance among Pregnant Women in Luanda, Angola: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study Cruz S. Sebastião 1,2,3 , Joana Morais 1,2,4 and Miguel Brito 1,5,* 1 Centro de Investigação em Saúde de Angola, Caxito, Angola; [email protected] (C.S.S.); [email protected] (J.M.) 2 Molecular Biology Laboratory, Instituto Nacional de Investigação em Saúde, Luanda, Angola 3 Instituto Superior de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade Agostinho Neto, Luanda, Angola 4 Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Agostinho Neto, Luanda, Angola 5 Health and Technology Research Center, Escola Superior de Tecnologia da Saúde de Lisboa, Instituto Politécnico de Lisboa, 1990-096 Lisboa, Portugal * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The increase in HIV infection and drug-resistant strains is an important public health concern, especially in resource-limited settings. However, the identification of factors related to the propagation of infectious diseases represents a crucial target offering an opportunity to reduce health care costs as well as deepening the focus on preventing infection in high-risk groups. In this study, we investigate the factors related to drug resistance among HIV-infected pregnant women in Luanda, the capital city of Angola. This was a part of a cross-sectional study conducted with 42 HIV-positive pregnant women. A blood sample was collected, and HIV-1 genotyping was carried out using an in-house method. Multivariate analyses were performed to determine the interaction between sociodemographic characteristics and drug resistance. HIV drug resistance was detected in 44.1% of the studied population. -

Antiretroviral Drug Resistance Testing in Adults with HIV Infection Implications for Clinical Management

Consensus Statement Antiretroviral Drug Resistance Testing in Adults With HIV Infection Implications for Clinical Management Martin S. Hirsch, MD; Brian Conway, MD; Richard T. D’Aquila, MD; Victoria A. Johnson, MD; Franc¸oise Brun-Ve´zinet, MD; Bonaventura Clotet, MD, PhD; Lisa M. Demeter, MD; Scott M. Hammer, MD; Donna M. Jacobsen; Daniel R. Kuritzkes, MD; Clive Loveday, MD, PhD; John W. Mellors, MD; Stefano Vella, MD; Douglas D. Richman, MD; for the International AIDS Society–USA Panel Objectives.—To review current knowledge of the biology and clinical implica- DEVELOPMENT of viral resistance to tions of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) resistance to antiretroviral drugs, de- antiretroviral drugs used for treatment scribe assays for measuring resistance, and assess their use in clinical practice. ofhumanimmunodeficiencyvirus(HIV) Participants.—The International AIDS Society-USA assembled a panel of 13 infection is an important cause of treat- 1-7 physicians with expertise in basic science, clinical research, and patient care rel- ment failure and limits options for al- ternative antiretroviral regimens. Pre- evant to HIV resistance to antiretroviral drugs. vention, characterization, and clinical Evidence.—We reviewed available data from published reports and presented managementofsuchresistanceisreceiv- at national and international research conferences. Basic science research, clini- ing increasing attention. The Interna- cal trial results, and expert opinions were used to form the basis of this report. Data tional AIDS Society–USA assembled a on methods for and characteristics of specific genotypic and phenotypic assays panel to review for clinicians the biologic were obtained from manufacturers and service providers. Consensus Process.—The panel met regularly between October 1997 and See also pp 1977 and 2000. -

HIV Drug Resistance Workshop: Basic Principles & Clinical Implications June 10–14 2008, Sitges, Spain Blank Page 11/6/08 12:31 Page 1 Prelims 19/5/08 11:19 Page Vii

HIV abstracts title 12/6/08 12:21 Page 1 Abstracts presented at the XVII International HIV Drug Resistance Workshop: Basic Principles & Clinical Implications June 10–14 2008, Sitges, Spain Blank page 11/6/08 12:31 Page 1 Prelims 19/5/08 11:19 Page vii HIV DRUG RESISTANCE w o r k s h o p basic principles & clinical implications June 10-14, 2008 • Sitges, Spain ORGANIZING COMMITTEE John Mellors, Chair University of Pittsburgh, USA Douglas Richman, Co-Chair and Course Director VA San Diego Healthcare System and University of California San Diego, USA Charles Boucher Erasmus Medical Center Rotterdam and University Hospital Utrecht, the Netherlands Brendan Larder RDI, UK SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Lee Bacheler VircoLab, Inc, USA Ralf Bartenschlager University Heidelberg, Germany Nick Cammack Roche Palo Alto, USA François Clavel Inserm U552, France Bonaventura Clotet Fundacio IRSI Caixa, Spain John Coffin National Cancer Institute-Frederick, USA Abel De La Rosa Pharmasset, USA Matthias Gotte McGill University, Canada Robert Grant Gladstone/UCSF, USA Michael Greenberg Trimeris, Inc., USA George Hanna Bristol-Myers Squibb, USA Richard Harrigan BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Canada Daria Hazuda Merck Research Labs, USA Nicholas Hellmann Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers Walid Heneine Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, USA Kurt Hertogs Tibotec bvba, Belgium Daniel Kuritzkes Brigham and Women's Hospital, USA Susan Little University of California, San Diego, USA Stephen Locarnini VIDRL, Australia Douglas Mayers Idenix Pharmaceuticals, USA -

Tech Award Winners Potential for Prep PWP Guidelines HIV Fatigue

THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF HIV MEDICINE www.aahivm.org APR. 2015 Patient Care, Practice Management & Professional Development Information for HIV CARE Providers HIVSpecialist Prevention & PrEP Tech Award Winners 8 Potential for PrEP 12 PWP Guidelines 26 HIV Fatigue 35 CONTENTS THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF HIV MEDICINE April 2015 | Volume 7, No. 1 | www.aahivm.org Specialist HIVPatient Care, Practice Management & Professional Development Information for HIV Care Providers FEATURES CHAIR/BOARD OF DIRECTORS Zelalem Temesgen, MD, AAHIVS 8 Hi Tech Weapons 26 Prevention & PrEP EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR James Friedman, MHA Guidelines: HIV Prevention with Against HIV Adults and Adolescents with HIV DIRECTOR OF MARKETING Tech Award Winners & COMMUNICATIONS Highlights of Updated CDC Amber McCracken Create Innovative Solutions Recommendations for to Improve Patient Care EDITOR HIV Care Providers Robert Gatty BY BOB GATTY G-Net Strategic Communications BY AMRITA TAILOR, MPH AND [email protected] KATHLEEN IRWIN, MD, MPH, FACPM, FIDSA PUBLICATION DESIGN 12 Prevention & PrEP AND ART DIRECTION The Potential for PrEP BonoTom Studio, Inc. 30 Prevention & PrEP 703-276-0612 BY GARY F. SPINNER, PA, MPH, AAHIVS Reinventing the Condom [email protected] for Success: A Global Crisis ADVERTISING of Marketing Myths Bill Spilman, President 15 Prevention & PrEP Innovative Media Solutions Tales from the Clinic BY DANNY RESNIC (877) 878-3260 toll-free, (309) 483-6467 direct [email protected] BY TRAVIS SHERER, PA-C, AAHIVS, GARY F. SPINNER, PA, MPH, AAHIVS AND 35 What Do We Mean PUBLISHER SUSAN LELACHEUR, PA-C The American Academy of HIV Medicine 1705 DeSales St., NW, Suite 700 by ‘HIV Fatigue?’ Washington, D.C. -

Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents

Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents January 29, 2008 Developed by the DHHS Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents – A Working Group of the Office of AIDS Research Advisory Council (OARAC) How to Cite the Adult and Adolescent Guidelines: Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adult and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services. January 29, 2008; 1-128. Available at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. Accessed (insert date) [insert page number, table number, etc. if applicable] It is emphasized that concepts relevant to HIV management evolve rapidly. The Panel has a mechanism to update recommendations on a regular basis, and the most recent information is available on the AIDSinfo Web site (http://AIDSinfo.nih.gov). January 29, 2008 What’s New in the Document? The following changes have been made to several sections of the December 1, 2007 version of the guidelines. What to Start: Initial Combination Regimens for the Antiretroviral-Naïve Patient? The Panel revised its recommendations for several “preferred” and “alternative” antiretroviral components for treatment-naïve patients: “Abacavir + lamivudine” has been changed from “alternative” to “preferred” 2-NRTI component in patients who have tested negative for HLA-B*5701 (AII). “Zidovudine + lamivudine” has been changed from “preferred” to “alternative” 2-NRTI component (BII). “Ritonavir-boosted saquinavir” has been changed from a PI-option that was considered as “Acceptable as initial antiretroviral components but inferior to preferred or alternative components” to an “alternative” PI component (BII).