Response to Its Real Developmental Needs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quad Cities Riverfront Council Meeting Agenda, May 25, 2021

Meeting Announcement and Agenda Quad Cities Riverfront Council (QCRFC) Tuesday, May 25, 2021 – 12:00 p.m. WEBINAR MEETING Due to on-going COVID-19 directives by state and federal officials for gatherings, the Quad Cities Riverfront Council will be held by webinar. QCRFC Representatives, general public, and media can join the meeting at https://zoom.us/j/97493101100?pwd=YUhoVDNOSmxQR1J3MUk3YUpMcGxHdz09 and Meeting ID: 974 9310 1100 Passcode: 746713. Or dial in +1-312-626-6799 US (Chicago) and Meeting ID: 974 9310 1100 Passcode: 746713 QCRFC Representatives Larry Burns, President (Rock Island County) Molly Otting-Carlson, Vice President (Visit Quad Cities) Jeff Reiter, Secretary/Treasurer (Bettendorf) Mr. Steve Ahrens/Mr. Bruce Berger (Davenport, IA) Mr. Geoff Manis (Moline, IL) Mayor Ray C. Allen/Mr. Justin Graff (LeClaire, IA) Mr. Olin Meador (Buffalo, IA) Mayor Michael Bawden (Riverdale, IA) Mayor Curt Morrow (Andalusia, IL) Mayor James Boone (Cordova, IL) Ms. Molly Otting Carlson (Visit Quad Cities)* Ms. Ann Geiger (National M.R.P.C.) Mayor Bruce Peterson (Port Byron, IL) Mr. John Gripp (Rock Island, IL) Mr. James Peterson (New Boston/Mercer County, IL) Mr. Ralph H. Heninger (Quad Cities Chamber of Mr. Jeff Reiter (Bettendorf, IA)* Commerce – Iowa Rep) ** Col. Steven Sattinger/Lt. Col. John Fernas Mr. Joel Himsl (Rock Island Arsenal) (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers) Ms. Missy Housenga (Rapids City, IL) Dr. Rodney Simmer/Mr. Larry Burns (Rock Island County, IL)* Mr. Carl Hoyt (LeClaire Chamber of Commerce) Mayor Richard Vershaw (Hampton, IL) Mr. Tim Huey (Scott County, IA) Ms. Kathy Wine (River Action, Inc.) Mr. -

River Drive Corridor Study Area

Table of Contents 0 Executive Summary Concept Goals ES-1 Concept Principles ES-2 Concept Components ES-3 Concept Framework ES-4 Character Areas ES-5 1 Concept Introduction 1.1 2 Observations & Analysis 2.1 Study Area 2.2 Related Plans & Initiatives 2.3 Existing Framework 2.7 Economic Perspective 2.13 3 Exploration & Visioning 3.1 Supplemental Visual Analysis 3.2 Public Workshop 3.5 Charette Studio: Alternative Scenarios 3.5 Public Open House 3.12 Steering Committee Work Session 3.13 Preliminary Preferred Direction 3.14 RIVER DRIVE CORRIDOR CONCEPT PLAN . CITY OF MOLINE, ILLINOIS DRAFT #3: OCTOBER 2009 Table of Contents 4 Concept Framework 4.1 Concept Goals 4.2 Concept Principles 4.3 Concept Components 4.5 Character Areas 4.7 The East Gateway 4.9 Moline Centre 4.12 Columbia Park 4.13 John Deere Business Anchor 4.14 Riverstone Riverfront Industrial Anchor 4.15 Riverfront Campus 4.18 Riverfront Campus - Neighborhood Center 4.19 Riverfront Business Campus 4.20 Riverfront Neighborhood 4.21 Floreciente Neighborhood 4.22 Parks and Open Space 4.23 Urban Design: Branding 4.24 Mobility 4.26 River Drive 4.26 IL-92 (4th and 6th Avenues) 4.31 Connectivity 4.33 Bus Rapid Transit & Transit Oriented Development 4.34 Trails 4.36 5 Implementation & Action 5.1 Critical Action: Policy 5.2 Critical Action: Organization 5.3 Critical Action: Marketing 5.4 Critical Action: Circulation 5.5 Critical Action: Catalyst Project Areas 5.7 Critical Action: Funding ‘Tool Box’ 5.12 Development Opportunities Matrix 5.16 DRAFT #3: OCTOBER 2009 RIVER DRIVE CORRIDOR CONCEPT PLAN . -

The Rock Island Arsenal and Rock Island in the World Wars

Western Illinois Historical Review © 2020 Volume XI, Spring 2020 ISSN 2153-1714 ‘Rock Island Needs Machinists’: The Rock Island Arsenal and Rock Island in the World Wars By Jordan Monson Western Illinois University “Availability of workers… was vital to the successful operation of Rock Island Arsenal in the World War, just as it must be in any future military crisis in which the country may become involved.”1 Industries and businesses have a huge impact on the development of a community. No business can be successful without labor provided by communities, and communities rarely grow without the availability of jobs provided by businesses. In this same way, the Rock Island Arsenal has had a huge impact on the surrounding communities of Rock Island, Moline, Davenport, and Bettendorf, collectively known as the Quad Cities. Indeed, in an article published in 2018, Aarik Woods points out that the Rock Island Arsenal is far and away the largest employer in the region, and the economic impact of the Arsenal on the Quad Cities was more than one billion dollars.2 With that large of an economic impact, it is safe to say that the success of the Arsenal and the success of the Quad Cities are tied at the hip. However, the Rock Island Arsenal often goes through extreme variation in production and employment numbers, with “The Arsenal’s employment and production traditionally being cyclical in nature… increasing during national emergencies and declining during peacetime.”3 These mobilization and demobilization patterns of the Arsenal were most pronounced during the period between the first and second world wars. -

Grant Number Organization Name Year Code Amount Awarded

(Page 1 of 98) Generated 07/01/2019 11:08:29 Grant Year Amount Organization Name Project Name Number Code Awarded 65 NOAH'S ARK COMMUNITY COFFEE HOUSE 4 $12,000.00 Neighborhood Advocacy Movement (1) 65 NOAH'S ARK COMMUNITY COFFEE HOUSE 5 $23,000.00 Neighborhood Advocacy Movement II 89 Bettendorf Park Band Foundstion 2 $6,500.00 Park Band Equipment 86 LECLAIRE YOUTH BASEBALL INC 3 $15,000.00 Field Improvement 16 LECLAIRE YOUTH BASEBALL INC 94 $1,500.00 Upgrade & Repair Baseball Field 604 WESTERN ILLINOIS AREA AGENCY ON AGING 96 $5,000.00 Quad City Senior Olympics 119 WESTERN ILLINOIS AREA AGENCY ON AGING 97 $5,000.00 Quad City Senior Olympics (2) 16 WESTERN ILLINOIS AREA AGENCY ON AGING 5 $3,000.00 RSVP - Upgrading of Sr. Choir Bells Encouraging the physical development of students: New playground at 047 Lourdes Catholic School 19 $10,000.00 Lourdes Catholic School 7 EAST DAVENPORT PONY LEAGUE 94 $2,000.00 Garfield Park Dugout Repairs 58 Alternatives (for the Older Adult, Inc.) 5 $1,900.00 Tools for Caregiving 48 Alternatives (for the Older Adult, Inc.) 8 $120.00 Tea For Two Fundraiser 046 Alternatives (for the Older Adult, Inc.) 18 $127,500.00 QCON HUB 65 HERITAGE DOCUMENTARIES, INC. 7 $10,000.00 Movie: When Farmers Were Heroes 85 HERITAGE DOCUMENTARIES, INC. 9 $15,000.00 The Andersonville of the North 17 HERITAGE DOCUMENTARIES, INC. 12 $15,000.00 Video: The Forgotten Explorer 29 HERITAGE DOCUMENTARIES, INC. 14 $10,000.00 East Meets West: The First RR Bridge 16 LIGHTS! RIVER! ACTION! FOUNDATION 91 $10,000.00 Centennial Bridge Lights Maintenance -

An Illustrated History of the Rock Island Arsenal and Arsenal Island

An Illustrated History Of The Rock Island Arsenal And Arsenal Island Part Two National Historic Landmark 71 FOREWORD On 11 July 1989 the Rock Island Arsenal commemorated its designation as a National Historic Landmark by the Secretary of the Interior. This auspicious occasion came about due in large measure to the efforts of the AMCCOM Historical Office, particularly Mr. Thomas J. Slattery, who spent many hours coordinating the efforts and actions necessary to bring the landmark status into fruition. Rock Island Arsenal Commander, Colonel David T. Morgan, Jr., was also instrumental in the implementation of the above ceremony by his interest, guidance, and support of Rock Island Arsenal’s National Historic Landmark, status. Incidental to the National Historic Landmark commemoration, the AMCCOM Historical Office has published An Illustrated History of Rock Island Arsenal and Arsenal Island, Part Two. Mr. Thomas J. Slattery is the author of this history and has presented a very well-written and balanced study of the beginning of Rock Island Arsenal in 1862 through 1900, including the arsenal construction period, the arsenal’s role in providing ordnance stores to the west, and its contributions during the Spanish-American War. This information was gathered from a number of primary and secondary sources including the author’s own files, the AMCCOM Historical Office archives, and the Rock Island Arsenal Museum collection. Mr. Slattery would like to acknowledge the efforts of past and present historians who gathered and preserved historical sources maintained in the holdings of these two institutions. Mr. Slattery is especially appreciative of the contributions made in this area by his colleagues Mr. -

War of 1812 by Beth Carvey the Sauk and Meskwaki and the War of 1812 Prelude to War the War of 1812 Was a Significant Event in S

War of 1812 by Beth Carvey The Sauk and Meskwaki and the War of 1812 Prelude to War The War of 1812 was a significant event in Sauk and Meskwaki history and also for many other native nations who resided along and near the Mississippi River. The War of 1812 was actually two wars: an international war fought between the United States and Great Britain in the east and an Indian war fought in the west. This article is the first of a four-part series which will explore the War of 1812 in terms of native peoples’ points of view, the military actions that occurred in the western frontier theater, and the consequences for the Sauk and Meskwaki that resulted from the American victory. In 1812 the western frontier was comprised of the Mississippi, Illinois, and Missouri River regions, encompassing parts of present-day Wisconsin, Illinois, and northwest Missouri. More than ten different native nations, including the Sauk and Meskwaki, lived on these lands with an estimated population of 25,000 people. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 the native people of the region had been growing increasingly unhappy with the United States. Four main reasons were at the heart of this unhappiness: arrogance and ignorance on the part of many American officials; illegal white settlement on native lands; a number of treaties that dispossessed tribes of their lands; and economic matters, specifically the fur trade. The Sauk and Meskwaki had poor relations with the United States government since the signing of the fraudulent Treaty of 1804, whereby the two nations ceded over 50 million acres of land to the United States. -

This Publication Is Published Weekly and Contains Information About, For, and of Interest to the Island Workforce

This publication is published weekly and contains information about, for, and of interest to the Island Workforce. Island Insight Submission: https://home.army.mil/ria/index.php/contact/public-affairs Sections: Arsenal Traffic/Construction Army Community (ACS) Building/Space Closures MWR Outdoor Recreation Active Duty/Reserve Zone Employee Assistance Program Safety Spotlight Education/Training Review Equal Employment Defense Commissary Agency/PX April 19-May 16: Virtual Run The Rock & Opportunity Focus Arsenal Archive America's Kids Run, Morale, Welfare & Recreation Healthbeat www.facebook.com/ArsenalRunTheRock (MWR) Notes for Veterans May: Asian Pacific American Heritage MWR Leisure Travel Office Around the Q.C. Month Child & Youth Services May: National Military Appreciation Month First Army Senior Guard Advisors Pulling Double Duty May: Month of the Military Caregiver to Battle COVID-19 May 3-9: Public Service Recognition Week Today, more than 45,000 members May 5: Cinco de Mayo of the National Guard are on duty May 8: Military Spouse Appreciation Day at the direction of their governors May 10: Mother's Day to support the response to the May 13: Children of Fallen Patriots Day COVID-19 pandemic. First Army May 15: Peace Officers Memorial Day May 16: Armed Forces Day is partnering with members of May 16-22: National Safe Boating Week state National Guards through May 18-22: DA Photos, Bldg. 90, Senior Army Advisors to the Basement, Rm. B11, 7:20 a.m. - 3:40 Army National Guard, also known as SRAAGs. First Army p.m. manages the SRAAGs assigned to the 50 states and the U.S. -

Razing Rico Building Closer Committee of the Whole Could Advance Plan SARAH HAYDEN [email protected]

50-year-old golf Moline school board reviews course sports dual-language program A3 new look B1 Skip-a-Long offers help for children A7 140TH YEAR · MOLINE, ILLINOIS Tuesday, May 8, 2018 | QCOnline.com | $1.50 167TH YEAR Razing RICo building closer Committee of the whole could advance plan SARAH HAYDEN [email protected] ROCK ISLAND — The courthouse is again moving toward possible demolition. On Monday morning, members of the Rock Island County Board’s Governance, Health and Administration committee approved a revised agreement with the Public Building Commission, allowing it to advance to the county board’s committee of the whole meet- ing on Wednesday. MEG MCLAUGHLIN PHOTOS / [email protected] If approved Wednesday, the agreement will Ken Duhm, of Moline, rides his bike past Mississippi River fl ood water along Ben Butterworth Parkway on Monday in Moline. The go to the regular meeting on May 15. National Weather Service fl ood warning remains in eff ect all along the Mississippi River in eastern Iowa and western Illinois until Committee members Cecilia O’Brien and further notice. The river is expected to rise to 17.8 feet Friday morning then begin falling. Mike Steffen attended Monday’s meeting by telephone conference. Scott Terry was absent. The new agreement states the commis- sion will retain funds through July 18 to cover asbestos abatement in the courthouse, Rising river closes streets demolish it and in- stall landscaping, “The PBC berms and security Moline, Davenport bollards to protect (Public the exterior of the close streets near new justice center Building unless the county Mississippi River board, by July 18, Commission) says the funds are STAFF REPORT not needed. -

Vol. XXXVIII No. 3 Sept. 1968 IOWA ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION

Vol. XXXVIII No. 3 Sept. 1968 Published by the IOWA ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION 66 IOWA BIRD LIFE - XXXVIII, 1968 VOL. XXXVIli No. 3 SEPT. 1968 PAGES 65-104 CONTENTS BIRDS IN THE DAVENPORT AREA 67 - 85 FALL CONVENTION 86-87 FIELD REPORTS 88-90 OBITUARIES 90-91 GENERAL NOTES 92-93 BOOK REVIEWS 93-95 MEMBERSHIP ROLL 96- 104 NEW MEMBERS 104 OFFICERS OF THE IOWA ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION President - Robert L. Nickolson, 2314 Helmer St., Sioux City, Iowa 51103 Vice-President - Mrs. Robert Vane, 2220 Grand Ave. S.E., Cedar Rapids, Iowa 52403, Secretary - Mrs. M. K. Hallberg, 4 Rock Bluff Road, Ottumwa, Iowa 52501 Treasurer - Woodward H. Brown, 4815 Ingersoll Ave., Des Moines, Iowa 50312. Editor - Peter C. Petersen Jr., 235 McClellan Blvd. Davenport, Iowa 52803 Librarian - Miss Frances Crouter, 2513 Walnut St. Cedar Falls, Iowa 50613 Executive Council: Keith Layton, Oskaloosa, Iowa Mrs. Charles Ayres, Ottumwa, Iowa Mrs. Russell Nicholson, Des Moines, Iowa Miss Myra Willis, Cedar Rapids, Iowa The Iowa Ornithologists' Union was organized at Ames, Iowa, February 28, 1923, for the study and protection of native birds and to promote fraternal relations among Iowa bird stu- dents. The central design of the Union's official seal is the Eastern Goldfinch, designated State Bird of Iowa in 1933. Publication of the Union: Mimeographed letters, 1923-1928; THE BULLETIN 1929-1930: IOWA BIRD LIFE beginning 1931. SUBSCRIPTION RATE: $3.00 a year, single copies 75£ each except where supply is limited to five or fewer copies, $1.00. Subscriptions to the magazine is included in all paid memberships, of which there are five classes as follows: Life Member, $100.00, payable in four equal installments: Contributing Mem- ber, $10,00 a year; Supporting Member, $5,00 a yean Regular Member, $3.00 a year; Junior Member (under 16 years of age), $1.00 a year. -

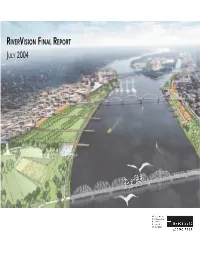

Rivervision Final Report July 2004 Table of Contents

RIVERVISION FINAL REPORT JULY 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY P.1 SECTION 1 - CONTEXT 1:1 INTRODUCTION P.3 1:2 PROJECT BACKGROUND P.3 1:3 SCHEDULE AND PROCESS P.3 SECTION 2 – PUBLIC INPUT & OPTION DEVELOPMENT 2:1 GUIDING OBJECTIVES P.5 2:2 URBAN DESIGN APPROACH OPTION DEVELOPMENT P.11 2:3 PUBLIC RESPONSE P.11 SECTION 3 – FINAL RECOMMENDATION CONSENSUS PLAN 3:1 OVERARCHING GOALS AND OBJECTIVES P.13 3:2 COMMON COMPONENTS & ISSUES P.13 3:3 DAVENPORT COMPONENTS & ISSUES P.19 3:4 ROCK ISLAND COMPONENTS & ISSUES P.29 3:5 ARSENAL ISLAND COMPONENTS & ISSUES P.37 3:6 PHASING P.39 3:7 RIVERVISION ECONOMIC BENEFITS P.43 3:8 SPONSORSHIP P.43 3:9 GENERAL IMPLEMENTATION P.43 APPENDIX P.48 4:1 ERA PRELIMINARY ECONOMIC REPORT P.49 4:2 PHASE 1 PUBLIC COMMENTS P.57 4:3 PHASE 2 PUBLIC COMMENTS P.61 Executive Summary RiverVision is a partnership between the cities of residential development with spectacular views at the Davenport, Iowa, and Rock Island, Illinois, to develop a river’s edge. Consensus Plan for their shared Mississippi riverfront. The Consensus Plan was developed over the course of 3. Create New Public Urban Parks Appropriate for Each seven months with input from the public on both sides of City the Mississippi River. The RiverVision process is a unique RiverVision introduces a new public urban park model for cooperation between two cities and states to infrastructure for both Davenport and Rock Island as achieve both shared regional objectives as well as projects public amenities, catalysts for development, and a means specifi c to the needs of each city. -

Rock Island Heritage Resources Plan

CITY OF ROCK ISLAND DRAFT HISTORIC RESOURCES PLAN MARCH 30, 2016 PREPARED BY THE LAKOTA GROUP ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS HISTORIC RESOURCES PLAN STAKEHOLDER COMMITTEE CITY OF ROCK ISLAND STAFF Dennis Pauley, Mayor of Rock Island Thomas Thomas, City Manager Andrew Dasso, Plan Commission Ben Griffith, Planning and Redevelopment Administrator David Levin, Plan Commission/Realtor Brandy Howe, Urban Planner II Brent Bogen, Preservation Commission Chair Alan Fries, Urban Planner II Sue Swords, Preservation Commission Jeff Eder, Assistant City Manager, and Community and Avalon Thomas-Roebal, Renaissance Rock Island Economic Development Director Diane Oestreich, Rock Island Preservation Society Randall D. Tweet, Director of Public Works Linda Anderson, Rock Island Preservation Society Tom Ayers, Chief Building Official Sheila Solomon, Neighborhood Representative Joe Taylor, Quad Cities Convention and Visitor’s Bureau Angela Campbell, Rock Island Public Library ROCK ISLAND PRESERVATION COMMISSION Commissioners Leigh Ayers Brent Bogan, Chair Elizabeth Anne DeLong Paul Fessler Anthony Heddlesten Craig Kavensky Brian Leech Italo (Lo) Milani This (product or activity) has been financed in John Strieter part with federal funds from the Department Susan Swords of the Interior, administered by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily Associate Members reflect the views or policies of the Department Linda Anderson of the Interior nor the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial Jeff Dismer products constitute endorsement or recommendation by Daryl Empen the Department of the Interior nor the Illinois Historic Diane Oestreich Preservation Agency.. This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and ROCK ISLAND CITY COUNCIL the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. -

Index: 150 Years of Epitaphs at Chippiannock Cemetery

Index: 150 Years of Epitaphs at Chippiannock Cemetery A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z A bankruptcy bootlegging A.D. Huesing Bottling Works Banner Coal & Coal Oil bottling Abbot, Minnie Estelle Company Bowling, Margaret Adams, Mary Ann Barker, Minnie Bowling, Sam African-American Barker, Wilbur boxing Ainsworth & Lynde Barnard & Leas Brackett, Ada Ainsworth, Calvin Barnard, H.A. Brackett, Joseph Ainsworth, Charles Barnes, M.S. Breese, Sidney Ainsworth, Charles Henry Barrett & Philleo brewer Ainsworth, Emma Barrett, Benjamin F. brewing Ainsworth, Lucia Barrett, Parkhurst & Emerson bricklayer Alabama Bartels, Mary brickyard Alaska Bastian, Carrie Bright's disease alderman Bastian, Eva Broadway Presbyterian Church Alexander, Margaret Bastian, Henry Brogniart, Alexandre-Theodore Allegheny College Bastian, Mildred Brooks, Jannette Allen, Archibald Bavaria brothel American Association of Bear, Jonas Brotherhood of American University Women Beardsley & Burgh Yoemen American House Beardsley, Jerome J. Brown, Eliza Ancient Order of United Beck, David Bryant & Stratton Workmen Beck, Elizabeth Buckingham, Louis Andalusia Beecher, Elizabeth Buford Plow Company Andreen, Gustav Bernhardt, Sarah Buford, Anne Andreen, Hilda Best Building Buford, Charles Andreen, Mary Best, Louis P. Buford, Clark Andreen, Rev. Andrew Bethany Home Buford, Felicia Andrews, Lemuel Betty, John Buford, Helen Angerer, Edward Betty, Mary Ann Buford, Herndon Anheuser-Busch Brewing Beverley & Burgh Buford, James Monroe Association Big Island Buford, Jane apoplexy Billburg, Anthony Buford, John appendicitis, appendix Billburg, Margaret Buford, Lucy Argus Billburg, Tom Buford, Mary Ann Arkansas Black Diamond Coal Company Buford, Nancy Army Corps of Engineers Black Hawk Buford, Napoleon Bonaparte Arsenal Island Black Hawk Mineral Springs Buford, Sarah artist Black Hawk Paper Company Buford, Simeon Athletic Club Black Hawk War Buford, Temple Atlantic Black Masons Buford, Thomas Jefferson (T.J.) Atlantic and Pacific Tea blacksmith Burgh, Carrie Company Blanding, V.