Biomedical Sciences 2 DRAFT 9/13/16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Functional Brain Imaging 1990–2009

Portfolio Review Human Functional Brain Imaging 1990–2009 September 2011 Acknowledgements The Wellcome Trust would like to thank the many people who generously gave up their time to participate in this review. The project was led by Claire Vaughan and Liz Allen. Key input and support was provided by Lynsey Bilsland, Richard Morris, John Williams, Shewly Choudhury, Kathryn Adcock, David Lynn, Kevin Dolby, Beth Thompson, Anna Wade, Suzi Morris, Annie Sanderson, and Jo Scott; and Lois Reynolds and Tilli Tansey (Wellcome Trust Expert Group). The views expressed in this report are those of the Wellcome Trust project team, drawing on the evidence compiled during the review. We are indebted to the independent Expert Group and our industry experts, who were pivotal in providing the assessments of the Trust’s role in supporting human functional brain imaging and have informed ‘our’ speculations for the future. Finally, we would like to thank Professor Randy Buckner, Professor Ray Dolan and Dr Anne-Marie Engel, who provided valuable input to the development of the timelines and report. The2 | Portfolio Wellcome Review: Trust Human is a Functional charity registeredBrain Imaging in England and Wales, no. 210183. Contents Acknowledgements 2 Key abbreviations used in the report 4 Overview and key findings 4 Landmarks in human functional brain imaging 10 1. Introduction and background 12 2 Human functional brain imaging today: the global research landscape 14 2.1 The global scene 14 2.2 The UK 15 2.3 Europe 17 2.4 Industry 17 2.5 Human brain imaging -

The Experimental Psychology Bulletin: June 2017

The Bulletin of The Society for Experimental Psychology and Cognitive Sciences June 2017 In this issue… pp 2 – 4 APA Convention Program pp 5 – 6 President’s Column: Advocating for Psychological Science p 8 Marching for Science pp 12 – 13 Reaching Out pp 14 – 15 SEPCS Lifetime Achievement Awards pp 16 – 17 SEPCS Early Career Achievement Awards SEPCS in the wild! pp 8 – 10 SEPCS Marching for Science! pp 12 – 13 SEPCS at SEPA and SSPP! Get the word out! Submit op-eds, photos, news, awards, advice, and more to Will Whitham at [email protected] You’re Invited! 125th APA Annual Convention Washington D. C. August 3rd through 6th! 2 Invited Address Paul Merritt (Georgetown University) If You Want to Rule the World, Become a Cognitive Psychologist! SEPCS Lifetime Achievement Award Morton Ann Gernsbacher (University of Wisconsin – Madison) Use of Laptops in College Classrooms: What do the Data Really Suggest? Invited Address Adam Green (Georgetown University) Cognitive & Neural Intervention to Enhance Creativity in Relational Thinking and Reasoning Presidential Address Anne Cleary (Colorado State University) How Metacognitive States Like Tip-of-the-Tongue and Déjà Vu Can Be Biasing 3 Symposium: Cognitive Science & Education Policy Chair: Robert Bjork (UCLA) Participants: Jeffrey Karpicke (Purdue University) Ian Lyons (Georgetown University) Kenneth Maton (University of Maryland, Baltimore County) Skill Building Session Using Technology to Easily Implement Testing Enhanced Learning Facilitated by Paul Merritt & Kruti Vekaria (Georgetown University) Juan Ventura, a Cognitive and Brain Sciences Ph.D. student at LSU, won the 2017 APA Travel Award and Ungerleider/Zimbardo Travel Scholarship. The Ungerleider/Zimbardo Travel Scholarship is awarded to the top 7 applicants of the APA Travel Award. -

Intelligence and Artificial Intelligence

We invite applications to participate in the 4th Intercontinental Academia dedicated to Intelligence and Artificial Intelligence Opening online session: 13-18 June 2021 1st workshop in Paris, France: 18-27 October 2021 2nd workshop in Belo Horizonte, Brazil: 6-15 June 2022 Call for fellows Deadline: March 31, 2021 (6 pm CET) The Intercontinental Academia (ICA) seeks to create a global network of future research leaders in which some of the very best early/mid-career scholars will work together on paradigm-shifting cross-disciplinary research, mentored by some of the most eminent researchers from across the globe. In order to achieve this high objective, we organize in a year three immersive and intense sessions. The experience is expected to transform the scholar's own approach to research, enhance their awareness of the work, relevance and potential impact of other disciplines, and to inspire and facilitate new collaborations between distant disciplines. Our aim is to make a real, yet volatile, intellectual cocktail that leads to meaningful exchange and long-lasting outputs. The theme Intelligence and Artificial Intelligence have been selected to provide a framework for stimulating intellectual exchange in 2021-2022. The past decades have witnessed an impressive progress in cognitive science, neuroscience and artificial intelligence. Beside the decisive scientific advances that have been accomplished in the analysis of brain activity and its behavioral counterparts or in the information processing sciences (machine learning, wearable sensors…), several fundamental and broader questions of deep interdisciplinary nature have been arising. As artificial intelligence and neuroscience/cognitive science seem to show significant complementarities, a key question is to inquire to which extent these complementarities should drive research in both areas and how to optimize synergies. -

Curriculum Vitae – Raymond Joseph Dolan

Curriculum Vitae – Raymond Joseph Dolan GMC registration: 1393329 MPS number: 184714 Nationality: Irish (Eire) Professional Address: Max Planck UCL Centre Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research Russell Square House 10-12 Russell Square London, WC1B 5EH Tel +44 203 108 7511 Fax +44 207 813 1445 Email: [email protected] Present Appointments: Mary Kinross Professor of Neuropsychiatry, Institute of Neurology, UCL. Director, Max Planck-UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry and Ageing. Previous Appointments: Founding Director, Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging at UCL (2006–2015). Head of Department, Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, ION (2002- 2015). Education: University: National University of Ireland (NUI) Medical School: University College Galway Medical School Degrees: 1977 MB, BCh, BAO (NUI) 1988 MD (NUI) Professional Credentials and Learned Societies: 1995 Fellow of Royal College of Psychiatrists (FRCPsych) 2000 Fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences (FMedSci) 2002 Fellow of Royal College of Physicians (FRCP) 2010 Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) 2010 Fellow of Society of Biology (FSB) 2011 Member of the Royal Irish Academy (Hon) (MRIA) 2011 Fellow of the Association for Psychological Science (APS) 2012 External Scientific Member of Max Planck Society (MPS) 2014 Elected Member of EMBO 2015 Member of European Academy of Sciences and Arts Awards and Prizes: Alexander Von Humboldt International Research Award (2004) Kenneth Craik Research Award (2006) Minerva Foundation Golden Brain Award (2006) Max Planck International -

António De Vasconcelos Xavier

By: André Vicente and Carlos Oliveira (Class 11º3) February 2011 In this work we are going to write about two of the greatest Portuguese scientists: António Xavier and António Damasio The choice was hard but we have chosen these scientists because they are our main inspirations in the scientific area. We hope that you enjoy reading their biographies! 2 Contents António Xavier Biography Work and Achievements António Damásio Biography Work and Achievements 3 António de Vasconcelos Xavier António Vasconcelos Xavier was born on 31 of August 1943 and died on 7 May 2006. He was considered the pioneer of Bio-inorganic chemistry worldwide. His work focused on the areas of Biochemistry, Protein Chemistry and Enzymology. Xavier was a man who had a very important role in the Portuguese biotechnology. He participated in the European Molecular Biology Organization and Laboratory and also founded the Institute of Chemical and Biological Technology. His work was important for the international development of Bioinorganic Chemistry and also other subjects such as Biochemistry and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. The nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy methodology was his election, despite being a very expensive technique and dependent on technological advances. The contribution of Xavier Antonio to the development of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance methodology in Portugal has recently been recognized with the institution of the António Xavier Award by one of the largest manufacturers of spectrometers: CERMAX - Center for Magnetic Resonance António Xavier. 4 António de Vasconcelos Xavier Relevant Distinctions: “Gulbenkian Fellowship” Medal, in 1970-1973. “Chevalier de l’Ordre des Palmes Academiques French Award”, in 1980. “Officier de l’ Ordre des Palmes Academiques French Award”, in 1988. -

Winners of the Brain Prize 2017

Ground-breaking research into learning honoured with the world’s largest brain research prize The Lundbeck Foundation's major research prize – The Brain Prize – goes this year to three UK-based brain researchers for explaining how learning is associated with the reward system of the brain. The prizewinners have found a key to understanding the mechanisms in the brain that lead to compulsive gambling, drug addiction and alcoholism. Sophie is surprised and delighted by the great applause she receives for the new way she plays a piece of music. The applause motivates her to continue learning and improving and, perhaps, even become a professional musician one day. The applause is an unexpected reward. This unexpected reward is associated with an increased release of the brain’s neurotransmitter dopamine in specific brain cells, stimulating learning and motivation. The three winners of the 2017 Brain Prize, English Peter Dayan, Irish Ray Dolan and German Wolfram Schultz, have identified how learning is linked with anticipation of reward, as in Sophie’s case, giving us fundamental knowledge about how we learn from our actions. Through animal testing, mathematical modelling and human trials, the three prizewinners have proven that the release of dopamine is not a response to the actual reward but to the difference between the reward we expect and the reward we actually receive. The greater the surprise, the more dopamine is released. The Brain Prize is for 1 million euros, or approximately 7.5 Danish kroner, and is the world's largest brain research prize. The organisation behind the prize is the Lundbeck Foundation, one of Denmark's largest sponsors of biomedical sciences research. -

3-2017 J Nathans' CV

Curriculum vitae January 2017 Jeremy Nathans Current Position: Professor Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics Department of Neuroscience Samuel Theobald Professor, Wilmer Eye Institute (Department of Ophthalmology) Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Investigator Howard Hughes Medical Institute Personal Data: Born July 31, 1958; New York City Married to Thanh Huynh. Children: Riva (born 7/88) and Rosalie (born 3/94) Business Address: 805 PCTB Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine 725 North Wolfe Street Baltimore, MD 21205 tel: 410-955-4679 FAX: 410-614-0827 e-mail: [email protected] Education: Massachusetts Institute of Technology B.S., Life Sciences 1979 B.S., Chemistry 1979 Stanford University School of Medicine Ph.D., Biochemistry (with David Hogness) 1985 M.D. 1987 Postdoctoral fellow, Genentech, Inc. (with Axel Ullrich) 1987 Professional Experience: Assistant Professor, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Department of Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Assistant Investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute 1988–1992 Associate Professor, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Department of Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Associate Investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute 1992-1996 Associate Professor, Department of Ophthalmology Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine 1993-1996 Professor, Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, 1 Department of Neuroscience, Department of Ophthalmology Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine 1996-present Investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute 1997-present Advisory and Grant Review Boards (past): Scientific Advisory Board, Zanvil Kreiger Mind–Brain Institute, J.H.U. 1991-1992 Scientific Advisory Board, The Ruth and Milton Steinbach Fund 1997-2007 Intramural Program Review Committee, National Eye Institute, N.I.H. -

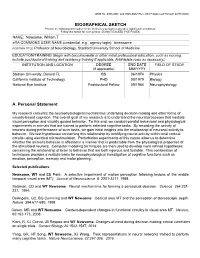

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH A. Personal Statement

OMB No. 0925-0001 and 0925-0002 (Rev. 09/17 Approved Through 03/31/2020) BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Provide the following information for the Senior/key personnel and other significant contributors. Follow this format for each person. DO NOT EXCEED FIVE PAGES. NAME: Newsome, William T eRA COMMONS USER NAME (credential, e.g., agency login): bnewsome POSITION TITLE: Professor of Neurobiology, Stanford University School of Medicine EDUCATION/TRAINING (Begin with baccalaureate or other initial professional education, such as nursing, include postdoctoral training and residency training if applicable. Add/delete rows as necessary.) INSTITUTION AND LOCATION DEGREE END DATE FIELD OF STUDY (if applicable) MM/YYYY Stetson University, Deland FL BS 06/1974 Physics California Institute of Technology PHD 08/1979 Biology National Eye Institute Postdoctoral Fellow 09/1984 Neurophysiology A. Personal Statement My research concerns the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying decision-making and other forms of visually-based cognition. The overall goal of my research is to understand the neural processes that mediate visual perception and visually guided behavior. To this end, we conduct parallel behavioral and physiological experiments in animals that are trained to perform selected cognitive tasks. By recording the activity of neurons during performance of such tasks, we gain initial insights into the relationship of neuronal activity to behavior. We test hypotheses concerning this relationship by modifying neural activity within local cortical circuits using electrical microstimulation. Perturbation experiments of this nature allow us to determine whether the animal’s behavior is affected in a manner that is predictable from the physiological properties of the stimulated neurons. Computer modeling techniques are then used to develop more refined hypotheses concerning the relationship of brain to behavior that are both rigorous and testable. -

Movshon 1 11/12/18 Joseph Anthony Movshon Center for Neural Science

Joseph Anthony Movshon Center for Neural Science 100 Bleecker Street, Apt 30D New York University New York, NY 10012, USA 4 Washington Place, Room 809 New York, NY 10003, USA Phone: +1 212-998-7880 +1 212-260-6535 Fax: +1 212-995-4183 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.cns.nyu.edu/corefaculty/Movshon.php Date of birth: 10 December 1950 Place of birth: New York, NY, USA Nationality: USA Education 1955–1968 The Browning School, New York, NY, USA 1968–1969 McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 1969–1975 Churchill College, University of Cambridge 1972 B. A. (Honours) 1972–1975 Research Student, The Psychological Laboratory, University of Cambridge 1975 Ph. D. (Supervisor: Colin Blakemore) Dissertation: Plasticity of Binocular Organization in the Kitten's Visual System 1976 M. A. Honors 1972–1975 Research Training Scholarship, The Wellcome Trust 1977–1981 Research Fellowship in Neuroscience, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation 1980–1985 Research Career Development Award, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health 1985 Young Investigator Award, Society for Neuroscience 1985–1986 Visiting Fellowship, All Souls College, Oxford 1985–1986 Royal Society Guest Research Fellowship, University Laboratory of Physiology, Oxford 1985–1986 Senior International Fellowship, Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health 1986 Fellow, New York Institute for the Humanities 1992 Rank Prize for Optoelectronics 1993 Herman and Margaret Sokol Faculty Award, New York University 1993 Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science 1996 Lamport Lectureship, University of Washington, Seattle 1999 Presidential Professorship, New York University 2000 W. R. Bauer Foundation Lectureship, Brandeis University 2002 Silver Professorship, New York University Movshon 1 11/12/18 2006 A. -

William Thomas Newsome, III

William Thomas Newsome, III Birth: June 5, 1952, Live Oak, Florida, USA Telephone: Office: (650) 725-5814 Fax: (650) 725-3958 Email: [email protected] Education: 1970-1974 B.S., Physics, summa cum laude, Stetson University, Deland, FL. 1974-1979 Ph.D., Biology, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA. Academic Positions: 2013-present Harman Family Provostial Professor, Stanford University 2013-present Director, Stanford Neurosciences Institute 1997-2019 Investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute 2008-2013 Director, BioX NeuroVentures, Stanford University 2005-2008 Chair, Department of Neurobiology, Stanford University School of Medicine 2000-2005 Director, Neurosciences Graduate Program, Stanford University 1993-present Professor, Department of Neurobiology, Stanford University School of Medicine 1995-1996 McDonnell-Pew Visiting Fellow, University of Oxford Senior Visiting Research Fellow, St. Johns College, Oxford 1988-1993 Associate Professor, Department of Neurobiology, Stanford University School of Medicine 1984-1988 Assistant Professor, Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, State University of New York at Stony Brook 1980-1984 Staff Research Fellow, Laboratory of Sensorimotor Research, National Eye Institute Research Interests: Central mechanisms in visual perception and visually-based cognition. Neural mechanisms underlying simple forms of decision making. Neural basis of motivation and reward, and their influence on decision- making. Professional Affiliations: Society for Neuroscience, American Association for -

Joseph Anthony Movshon

Joseph Anthony Movshon Center for Neural Science 100 Bleecker Street, Apt 30D New York University New York, NY 10012, USA 4 Washington Place, Room 621 New York, NY 10003, USA Phone: +1 212-998-7880 +1 212-260-6535 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.cns.nyu.edu/corefaculty/Movshon.php ORCID: 0000-0002-0274-9213 Date of birth: 10 December 1950 Place of birth: New York, NY, USA Nationality: USA Education 1955–1968 The Browning School, New York, NY, USA 1968–1969 McGill University, Montréal, Québec, Canada 1969–1975 Churchill College, University of Cambridge 1972 B. A. (Honours) 1972–1975 Research Student, The Psychological Laboratory, University of Cambridge 1975 Ph. D. (Supervisor: Colin Blakemore) Dissertation: Plasticity of Binocular Organization in the Kitten's Visual System 1976 M. A. Honors 1972–1975 Research Training Scholarship, The Wellcome Trust 1977–1981 Research Fellowship in Neuroscience, Alfred P. Sloan Foundation 1980–1985 Research Career Development Award, National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health 1985 Young Investigator Award, Society for Neuroscience 1985–1986 Visiting Fellowship, All Souls College, Oxford 1985–1986 Royal Society Guest Research Fellowship, University Laboratory of Physiology, Oxford 1985–1986 Senior International Fellowship, Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health 1986 Fellow, New York Institute for the Humanities 1992 Rank Prize for Optoelectronics 1993 Herman and Margaret Sokol Faculty Award, New York University 1993 Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science 1996 Lamport Lectureship, University of Washington, Seattle 1999 Presidential Professorship, New York University 2000 W. R. Bauer Foundation Lectureship, Brandeis University 2002 Silver Professorship, New York University Movshon 1 12/18/20 2006 A. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Daniel Mark

CURRICULUM VITAE Daniel Mark Wolpert FMedSci FRS Professor of Neuroscience Zuckerman Mind Brain Behavior Institute, Department of Neuroscience, Columbia University, Email [email protected] New York, United States Homepage www.wolpertlab.org Education 1985 Medical Sciences BA University of Cambridge 1988 Clinical Medicine BM BCh University of Oxford 1992 Physiology D. Phil University of Oxford Professional History 1988-89 Medical House Officer, Oxford 1989-92 Medical Research Council Training Fellow Physiology, University of Oxford (Supervisor: John Stein/Chris Miall) 1992-95 Postdoctoral Associate, Department of Brain & Cognitive Science McDonnell-Pew Fellow in Cognitive Neuroscience Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Supervisor: Michael Jordan) 1995-99 Lecturer in Neurophysiology, Institute of Neurology University College London 1999-02 Reader in Motor Neuroscience, Institute of Neurology, University College London 1999-05 Co-director, Institute of Movement Neuroscience 2002-05 Professor of Motor Neuroscience Vice-Chair, Sobell Department of Motor Neuroscience & Movement Disorders, Institute of Neurology, University College London 2005-08 Honorary Senior Research Fellow, UCL 2005-18 Professor of Engineering (1875), Department of Engineering, University of Cambridge 2005-18 Professorial Fellow, Trinity College, University of Cambridge 2012-18 Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator 2013-18 Royal Society Noreen Murray Research Professor 2018- Director or Research, Department of Engineering, University of Cambridge 2018- Professor of