Management Plan for Bighorn Sheep in Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air

Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) Summits on the Air Canada (Alberta – VE6/VA6) Association Reference Manual (ARM) Document Reference S87.1 Issue number 2.2 Date of issue 1st August 2016 Participation start date 1st October 2012 Authorised Association Manager Walker McBryde VA6MCB Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged Page 1 of 63 Document S87.1 v2.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for Canada (Alberta – VE6) 1 Change Control ............................................................................................................................. 4 2 Association Reference Data ..................................................................................................... 7 2.1 Programme derivation ..................................................................................................................... 8 2.2 General information .......................................................................................................................... 8 2.3 Rights of way and access issues ..................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Maps and navigation .......................................................................................................................... 9 2.5 Safety considerations .................................................................................................................. -

Long-Toed Salamander (Ambystoma Macrodactylum) Monitoring Study in Alberta: Summary Report 1998-2001

Long-toed Salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum) Monitoring Study in Alberta: Summary Report 1998-2001 Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 36 Long-toed Salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum) Monitoring Study in Alberta: Summary Report 1998-2001 Mai-Linh Huynh Lisa Takats and Lisa Wilkinson Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 36 January 2002 Project Partners: Publication No.: I/053 ISBN: 0-7785-2002-1 (Printed Edition) ISBN: 0-7785-2003-X (On-line Edition) ISSN: 1496-7219 (Printed Edition) ISSN: 1496-7146 (On-line Edition) Illustration: Brian Huffman For copies of this report, contact: Information Centre – Publications Alberta Environment / Alberta Sustainable Resource Development Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 108 Street Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T5K 2M4 Telephone: (780) 422-2079 OR Information Service Alberta Environment / Alberta Sustainable Resource Development #100, 3115 12 Street NE Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2E 7J2 Telephone: (403) 297-3362 OR Visit our web site at: http://www3.gov.ab.ca/srd/fw/riskspecies/ This publication may be cited as: Huynh, M., L. Takats and L. Wilkinson. 2002. Long-toed salamander (Ambystoma macrodactylum) monitoring study in Alberta: summary report 1998-2001. Alberta Sustainable Resource Development, Fish and Wildlife Division, Alberta Species at Risk Report No. 36. Edmonton, AB. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................ -

The Letters F and T Refer to Figures Or Tables Respectively

INDEX The letters f and t refer to figures or tables respectively "A" Marker, 312f, 313f Amherstberg Formation, 664f, 728f, 733,736f, Ashville Formation, 368f, 397, 400f, 412, 416, Abitibi River, 680,683, 706 741f, 765, 796 685 Acadian Orogeny, 686, 725, 727, 727f, 728, Amica-Bear Rock Formation, 544 Asiak Thrust Belt, 60, 82f 767, 771, 807 Amisk lowlands, 604 Askin Group, 259f Active Formation, 128f, 132f, 133, 139, 140f, ammolite see aragonite Assiniboia valley system, 393 145 Amsden Group, 244 Assiniboine Member, 412, 418 Adam Creek, Ont., 693,705f Amundsen Basin, 60, 69, 70f Assiniboine River, 44, 609, 637 Adam Till, 690f, 691, 6911,693 Amundsen Gulf, 476, 477, 478 Athabasca, Alta., 17,18,20f, 387,442,551,552 Adanac Mines, 339 ancestral North America miogeocline, 259f Athabasca Basin, 70f, 494 Adel Mountains, 415 Ancient Innuitian Margin, 51 Athabasca mobile zone see Athabasca Adel Mountains Volcanics, 455 Ancient Wall Complex, 184 polymetamorphic terrane Adirondack Dome, 714, 765 Anderdon Formation, 736f Athabasca oil sands see also oil and gas fields, Adirondack Inlier, 711 Anderdon Member, 664f 19, 21, 22, 386, 392, 507, 553, 606, 607 Adirondack Mountains, 719, 729,743 Anderson Basin, 50f, 52f, 359f, 360, 374, 381, Athabasca Plain, 617f Aftonian Interglacial, 773 382, 398, 399, 400, 401, 417, 477f, 478 Athabasca polymetamorphic terrane, 70f, Aguathuna Formation, 735f, 738f, 743 Anderson Member, 765 71-72,73 Aida Formation, 84,104, 614 Anderson Plain, 38, 106, 116, 122, 146, 325, Athabasca River, 15, 20f, 35, 43, 273f, 287f, Aklak -

Grinnell's Glacier

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1990 Grinnell's Glacier Gerald Allen Diettert The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Diettert, Gerald Allen, "Grinnell's Glacier" (1990). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2485. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2485 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mike and Maureen MANSFIELD LIBRARY Copying allowed as provided under provisions of the Fair Use Section of the U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW, 1976. Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's written consent. MontanaUniversity of GRINNELL'S GLACIER Gerald A. Diettert B.A., University of Montana, 1984 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1990 Approved by: Chairman, Board of Examiners ean. Graduate School Cl.-us*s. 24. Date /J UMI Number: EP36191 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

65094Chernoff.Pdf

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2001 Modeling plant diversity and post-fire regeneration in a 31-year-old burn-Vermilion Pass, Canadian Rockies Chernoff, Gregory William Chernoff, G. W. (2001). Modeling plant diversity and post-fire regeneration in a 31-year-old burn-Vermilion Pass, Canadian Rockies (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/22043 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/41211 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Modeling Plant Diversity and Post-Fire Regeneration in a 31 -Year-Old Bum - Vermilion Pass, Canadian Rockies Gregory William Chemoff A THESIS SUBMITIED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY CALGARY, ALBERTA AUGUST 2001 8Gregory Wliarn Chemoff 2001 National Library BibliotMque nationale 1+1 OfCanada du Canada uisitions and Acquisitions el 7.Bi tographic Services services bibliographiques 395 W.llircgkn Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 OltawaON K1AON4 CPMdQ - The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Lidnary of Canada to Bibiioth&quenationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduke, pr&er, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

Looking Directly at Opabin Pass, with Mount Biddle on the Left and Wenkchemna Peak on the Right

Looking directly at Opabin Pass, with Mount Biddle on the left and Wenkchemna Peak on the right. There is actually some glacier underneath all the rock visible in the lower left part of this photo, so it probably isn't as easy or safe to walk along that terrain as it may look from here: ! ! The views from here are incredible, and it would have been nice to have more time to explore this area (since it's a long hike from Moraine Lake, however, there generally isn't much time for a day-hiker to explore the pass and surrounding area). The prominent pass just left of center in the photo is called Misko Pass: ! ! Looking down on the two tiny glacial lakes on the western side of the Prospectors Valley: ! ! I climbed down towards the valley a short distance to get another panorama looking along the Prospectors Valley: ! ! ! I think the valley which contains Kaufmann Lake joins the Prospectors Valley just around the bend in the upper left of this photo: ! ! One last view looking up at the impressive Neptuak Mountain: ! ! This small glacial lake and nearby snow-patch looked interesting to check out, but we were short on time and decided to head back the way we had come. Note the windbreaks to the left in this photo, which I'm guessing are probably used by climbers or hikers who are camping here for a night: ! ! Looking back along the ridge at Wenkchemna Pass (below center in the photo), with Wenkchemna Peak above it: ! ! Again looking over at the peaks on the northern side of the Paradise Valley. -

Grizzlybearphva (1999).Pdf

THE GRIZZLY BEAR OF THE CENTRAL ROCKIES ECOSYSTEM (Ursus arctos) POPULATION AND HABITAT VIABILITY ASSESSMENT Seebe, Alberta, Canada 28 – 31 January, 1999 Workshop Financial Sponsors World Wildlife Fund Canada Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers Workshop Organizers The Eastern Slopes Grizzly Bear Project (ESGBP) Conservation Breeding Specialist Group (CBSG/SSC/IUCN) Environmental Science Program, Faculty of Environmental Design, University of Calgary Environmental Management and Sustainable Development Program, Faculty of Management, University of Calgary Workshop Hosts The Eastern Slopes Grizzly Bear Project A contribution of the Eastern Slopes Grizzly Bear Project, Calgary, Alberta, Canada and workshop participants in collaboration with IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group. Financial sponsors of this workshop were World Wildlife Fund Canada and The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. Cover photo courtesy of Corel® Corporation. Cover map courtesy of Scott Jevons, Geoworks GIS. Herrero, S., P.S. Miller, and U.S. Seal (eds.). 2000. Population and Habitat Viability Assessment for the Grizzly Bear of the Central Rockies Ecosystem (Ursus arctos). Eastern Slopes Grizzly Bear Project, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada and Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, Apple Valley, Minnesota, USA. Additional copies of this publication can be ordered through the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, 12101 Johnny Cake Ridge Road, Apple Valley, MN 55124 USA. Fax: 612-432-2757. Send checks for US$35 -

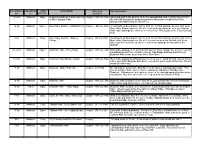

Hike Description 5-8 Km Minimal Easy Botanical Gardens

Hike Distance Hike Elevn HIKE HIKE NAME Hike Area Hike Description km m RATING (Location) 5-8 km Minimal Easy Botanical Gardens of Silver Springs Calgary - NW City Park Meet and park in the parking lot by the baseball diamond – not the soccer field. to Silver Springs Falls We will walk through the botanical gardens followed by a walk to the Silver Springs waterfall next to the Bow River. 12 km Minimal Easy + Bow Valley Ranche - Mallard Point Calgary - SE City Park Head South on Bow Bottom Trail to Fish Creek Park and take the first right to the Bow Valley Ranche parking. We will head northeast along the river on a flat trail. Bald eagle sightings are common on this stretch. This is part of the Trans Canada Trail 8 km Minimal Easy Bow Valley Ranche - Osprey Calgary - SE City Park Head South on Bow Bottom Trail to Fish Creek Park and take the first right to the Refuge Bow Valley Ranche parking. We will hike west on a mostly flat trail, with a few hills to get the heart rate up. Beaver and Heron sightings are possible in the Spring!! 10-12 km Minimal Easy + Bowmont Park - Home Road Calgary - NW City Park Start at the parking lot on 52nd St NW (just off Home Road). We wil then head off towards Bowmont Park, cross the Stoney Trail Bridge and loop back through Bowness Park on the south side of the Bow River. 5-8 km Minimal Easy Bowmont Park-Shorter version Calgary - NW City Park Meet in the parking lot of Marantha Church at 2023 - 52nd St. -

Picturesque Atlas of Australasia Maps

A-Signal Battery. I-Workshops. B-Observatory . K-Government House. C-Hospital. L-Palmer's Farm. .__4 S URVEY D-Prison. M-Officers ' Quarters. of E-Barracks . N-Magazine. F-Store Houses. 0-Gallows. THE SET TLEMENT ;n i Vh u/ ,S OUTN ALES G-Marine Barracks . P-Brick-kilns. H-Prisoners ' Huts. Q-Brickfields. LW OLLANI) iz /` 5Mile t4 2 d2 36 Engraved by A.Dulon 4 L.Poates • 1FTTh T i1111Tm»iTIT1 149 .Bogga 1 a 151 Bengalla • . l v' r-- Cootamundra Coola i r A aloe a 11lichellago 4 I A.J. SCALLY DEL. , it 153 'Greggreg ll tai III IJL. INDEX TO GENERAL MAP OF NE W SOUTH W ALES . NOTE -The letters after the names correspond with those in the borders of the map, and indicate the square in which the name will be found. Abercrombie River . Billagoe Mountain Bundella . J d Conjurong Lake . Dromedary Mountain. Aberdeen . Binalong . Bunda Lake C d Coogee . Drummond Mountain. Aberfoyle River . Binda . Bundarra . L c Cook (county) . Dry Bogan (creek) Acacia Creek . Bingera . Bunganbil Hill G g Coolabah . Dry Lake . Acres Billabong . Binyah . Bungarry Lake . E g Coolaburrag u ndy River Dry Lake Adelong Bird Island Bungendore J h Coolac Dry Lake Beds . Adelong Middle . Birie River Bungle Gully I c Coolah . Dry River . Ailsa . Bishop 's Bridge . Bungonia . J g Coolaman . Dubbo Creek Albemarle Black Head Bunker 's Creek . D d Coolbaggie Creek Dubbo Albert Lake . Blackheath Bunna Bunna Creek J b Cooleba Creek Duck Creek Albury . Black Point Bunyan J i Cooma Dudanman Hill . Alice Black Swamp Burbar Creek G b Coomba Lake Dudley (county) . -

Are Single Industry Towns Diversifying? (IS 931 A4)

Are single industry towns diversifying? (IS 931 A4) Spring 1992 (Vol. 4, No. 1) Article No. 4 Are single industry towns diversifying? A look at fishing, mining and wood-based communities Heather Clemenson The early history of forestry and mineral resource exploitation in Canada is synonymous with the term "company town." Isolated, small and completely controlled by one company, many of these settlements were temporary while others became a permanent feature of the Canadian landscape. Today, few communities are the sole property of a single company. But, for many towns, a single industry continues to be the main employer. These communities are the subject of this study. Though some single industry towns are dependent on tourism, government administration, defence, agriculture, or textile industries for employment, this study focuses only on three types of resource-based communities: fishing and fish processing, mining and refining, and wood-based activities (see Single sector communities study group). The objective is to examine some of the labour force and industry changes that have taken place in these towns since 1971, and to assess whether these settlements have become more dependent or more industrially diversified. The 1981-82 recession had an adverse impact on employment in resource dependent towns across Canada, which has refocused attention on the future of many of these communities. At issue is their long- term sustainability. If the economic base of a single industry town is in any way threatened, whether by market fluctuations (domestic or international), resource depletion, product substitution, technological change or any other factor, the future of the entire settlement can be at risk. -

Annotated Bibliography on the Geology of Selenium

Annotated Bibliography ~ ~ on the Geology 1""'1 ~ of Selenium ""'Q) t: ' en.= ""; c.> 'c;D 0 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1019-M 0 Q) C!5 ~ ~ zH """~ ~ en. ~ 0 l;o-4 0 0 ~ 0 ~ 0 ~ =E-t z 0 ~ =A-4 ~ C!5 0 ~ -~ -IXl ~ ~ E-t ~ E-i 0 z~ -<l J ....t ~ ~ Annotated Bibliography on the Geology of Selenium By GWENDOLYN W. LUTTRELL CONTRIBUTIONS TO BIBLIOGRAPHY OF MINERAL RESOURCES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1019-M Contains references on geologic occur rence, mineralogy, geochemistry, metal lurgy, analytical procedures, biologic effects, production, and uses of selenium UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1959 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRED A. SEATON, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director The U. S. Geological Survey Library has cataloged this publication as follows: Luttrell, Gwendolyn Lewise (Werth) 1927- Annotated bibliography on the geology of selenium. Washington, U. S. Govt. Print. Off., 1959. iii, 867-972 p. maps (1 fold. in pocket) 25 em. (U. S. Geological Survey. Bulletin 1019-M. Contributions to bibliography of mineral resources) 1. Selenium-Bibl. I. Title: The geology of selenium. (Series: U. S. Geological Survey. Bulletin 1019-M. Series: U. S. Geological Survey. Contributions to bibliography of mineral resources) 016.55349 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing, Office Washing,ton 25, D. C. - Price 50 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract---------------------------------------------------------- 867 Introduction------------------------------------------------------ -

Nature Alberta Magazine Spring 2011

VOLUME 41 | NUMBER 1 | SPRING 2011 SUGGESTED RETAIL: $7.50 CDN Nature Alberta CELEBRATING OUR NATURAL HERITAGE TREE SWALLOWS. SANDRA HAWKINS feature article Picturing Love of Nature NATURE ALBERTA GRIZZLY BEAR MOTHER AND CUB IN THE FOOTHILLS. KIRK DAVIS PYRAMID LAKE, JASPER NATIONAL PARK. ASHLEY HOCKENBERRY SPRING 2011 1 Nature Alberta: Nature Alberta is composed of natural history clubs from across the province. The aims of the Federation are: Celebrating our natural heritage (a) To encourage among all Albertans, by all means possible, an increase in their knowledge of natural history and understanding of ecological processes; (b) To promote an increase in the exchange of information and views among natural history clubs and societies in Alberta; (c) To foster and assist in the formation of additional natural history clubs and societies in Alberta; (d) To promote the establishment of natural areas and nature reserves, to conserve and protect species, communities or other features of interest; (e) To organize, or coordinate symposia, conferences, fi eld meetings, Contents nature camps, research and other activities whether of a similar or NATURE ALBERTA VOLUME 41, NUMBER 1, SPRING 2011 dissimilar nature; (f) To provide the naturalists of Alberta with a forum in which questions relating to the conservation of the natural environment may be discussed, so that united positions can be developed on them, and to President’s Report 2010 BY CHUCK PRIESTLEY ..................................................2 provide the means of translating these