Are Vanikoro Languages Really Austronesian?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Malaita

Ministry of Environment, Climate Change, Disaster Management & Meteorology Post Office Box 21 Honiara Solomon Islands Phone: (677) 27937/ 27936, Mobile: 7495895/ 7449741 Fax: (677) 24293 and 27060. e-mail : [email protected] and [email protected] 6 FEBRUARY TEMOTU EARTHQUAKE AND TSUNAMI SI NDMO/NEOC SITUATION REPORT NUMBER 05 Event 8.0 Earthquake and tsunami near Santa Cruz Islands, Temotu Province. SITREP No. 05 Date: 11/2/2013 Time Issued: 1800 Hrs Next Update: 1800hrs - 12/02/2013 From: NEOC/NDMO To: N-DOC & NDC Chairs and Members, P-DOC and PDC Chairs and Members, PEOCs Copies: NDMO Stakeholders, Donor Partners, Local & International NGOs, UN Agencies, Diplomatic Agencies, SIRPF, SIRC and SI Government Ministries and all SI Government Overseas Missions Situation New information highlighted in red. At 12.12pm Wednesday 6th February, 2013 a 8.0 magnitude undersea earthquake occurred 33km West- Southwest of the Santa Cruz Islands and generated a destructive tsunami. At 12.23pm the SI Meteorological Service issued a tsunami warning for 5 provinces in Solomon Islands; Temotu, Malaita, Makira-Ulawa, Central and Guadalcanal. By 1.18pm the threat to the 5 Provinces had been assessed and for Guadalcanal and Temotu this was downgraded to watch status. The tsunami warning remained in effect for Temotu, Makira-Ulawa and Malaita Provinces until 5pm. A large number of aftershocks have occurred after the event, with 7.1 being the highest. The Temotu Provincial Emergency Operations Centre (PEOC) was activated and a team was deployed to the Temotu province to assist the provincial staff Areas Affected Mostly the coastal villages on Santa Cruz. -

Vol. XIV, No. 2, March, 1951 277 This Report, a Supplement to an Earlier One1, on the Bees of the Solomon Islands Has Been Occas

Vol. XIV, No. 2, March, 1951 277 Additional Notes on the Bees of the Solomon Islands (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) By KARL V. KROMBEIN BUREAU OF ENTOMOLOGY AND PLANT QUARANTINE, AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH ADMINISTRATION, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE This report, a supplement to an earlier one1, on the bees of the Solomon Islands has been occasioned by the study of material in the collections of the California Academy of Sciences [CAS] and Museum of Comparative Zoology [MCZ] kindly made available by E. S. Ross and J. C. Bequaert, respectively. The diligent collecting on several of these islands during the war by G. E. Bohart has resulted in the present re cording of several forms previously unknown from the group, some new and some adventive from other regions. The material at hand has been extensive enough to enable me to present keys, complete or nearly so, to the species of Megachile and Halictus, the two largest genera of bees in the Solomons. The bee fauna now known to be present in the Solomons is listed be low (an asterisk denotes an endemic or supposedly endemic species). The honey bee, Apis mellifera L., has not been taken in the Solomons, though it occurs on several of the other islands in the Pacific. COLLETIDAE *Palaeorhiza tetraxantha (Cockerell). Guadalcanal, Russell and Florida HALICTIDAE Halictus (Indohalictus) dampieri Cockerell. Florida and Guadalcanal Halictus (Indohalictus) zingowli Cheesman and Perkins. Santa Cruz Islands, Guadal canal and Bougainville ♦Halictus (Indohalictus) froggatti Cockerell. Guadalcanal Halictus (Homalictus) fijiensis Perkins and Cheesman. San Cristobal ^Halictus (Homalictus) viridiscitus Cockerell. Florida *Halictus (Homalictus) exterus Cockerell. Florida and Guadalcanal *Halictus (Homalictus) pseudexterus sp. -

Ahp Disaster Ready Report: Traditional Knowledge

AHP DISASTER READY REPORT: TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE Tadahadi Bay, 2018. Prepared by: Kayleen Fanega, Project Officer, Solomon Islands Meteorological Services Acknowledgments This report was compiled by the Solomon Islands Meteorological Services (SIMS) climate section that have been implementing a Traditional Knowledge project with support and seed funding from the Government of Australia through Bureau of Meteorology, Australia with additional funding support from the Solomon Islands Government which has enabled data collection field trips. Solomon Islands Meteorological Service would like to kindly acknowledge and thank the World Vision Solomon Islands, for involving them in their Australian Humanitarian Project (AHP) and the communities; Tadahadi, Wango, Manitawanuhi, Manihuki for allowing the traditional knowledge (TK) survey to be conducted in their community. 1 Acronyms AHP: Australian Humanitarian Project BoM -Bureau of Meteorology MOU- Memorandum of Understanding TK- Traditional Knowledge SIMS- Solomon Islands Meteorological Services VDCRC- Village Disaster Climate Risk Committee WVSI- World Vision Solomon Islands 2 Contents Acknowledgments...................................................................................................................... 1 Acronyms ................................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... -

Sociological Factors in Reefs-Santa Cruz Language Vitality: a 40 Year Retrospective

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Sociological factors in Reefs-Santa Cruz language vitality: a 40 year retrospective BRENDA H. BOERGER, ÅSHILD NÆSS, ANDERS VAA, RACHEL EMERINE, and ANGELA HOOVER Abstract This article looks back over 40 years of language and culture change in the region of the Solomon Islands where the four Reefs-Santa Cruz (RSC) lan- guages are spoken. Taking the works of Davenport and Wurm as a starting point, we list specific linguistic changes we have identified and discuss the so- ciological factors which have both promoted and undermined the vitality of these languages. We then determine the level of vitality for each language through the recently proposed Extended Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale — EGIDS (Lewis and Simons 2010), and based on our results for the RSC languages, we provide a short evaluation of the usefulness of EGIDS for prioritizing language documentation efforts. Keywords: Solomon Islands; Solomon Islands Pijin; Reefs-Santa Cruz; Natügu; Nalögo; Nagu; Äiwoo; EGIDS; language documenta- tion; language vitality. 1. Introduction Forty years ago, two authors wrote extensively about the anthropological and linguistic situation in the RSC language communities. Davenport (1962, 1964, 1975, 2005) described the cultural and sociological properties of both the Santa Cruz and Reef Islands cultures, Figure 1, including a description of trade rela- tionships within the Santa Cruz archipelago. At the same time Wurm (1969, 1970, 1972, 1976, 1978) analyzed the linguistic characteristics of the RSC languages. In his later work, Wurm (1991, 1992a, 1992b, 2000, 2002, 2003) also discussed language vitality in the region. -

Recent Dispersal Events Among Solomon Island Bird Species Reveal Differing Potential Routes of Island Colonization

Recent dispersal events among Solomon Island bird species reveal differing potential routes of island colonization By Jason M. Sardell Abstract Species assemblages on islands are products of colonization and extinction events, with traditional models of island biogeography emphasizing build-up of biodiversity on small islands via colonizations from continents or other large landmasses. However, recent phylogenetic studies suggest that islands can also act as sources of biodiversity, but few such “upstream” colonizations have been directly observed. In this paper, I report four putative examples of recent range expansions among the avifauna of Makira and its satellite islands in the Solomon Islands, a region that has recently been subject to extensive anthropogenic habitat disturbance. They include three separate examples of inter-island dispersal, involving Geoffroyus heteroclitus, Cinnyris jugularis, and Rhipidura rufifrons, which together represent three distinct possible patterns of colonization, and one example of probable downslope altitudinal range expansion in Petroica multicolor. Because each of these species is easily detected when present, and because associated localities were visited by several previous expeditions, these records likely represent recent dispersal events rather than previously-overlooked rare taxa. As such, these observations demonstrate that both large landmasses and small islands can act as sources of island biodiversity, while also providing insights into the potential for habitat alteration to facilitate colonizations and range expansions in island systems. Author E-mail: [email protected] Pacific Science, vol. 70, no. 2 December 16, 2015 (Early view) Introduction The hypothesis that species assemblages on islands are dynamic, with inter-island dispersal playing an important role in determining local community composition, is fundamental to the theory of island biogeography (MacArthur and Wilson 1967, Losos and Ricklefs 2009). -

The Naturalist and His 'Beautiful Islands'

The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific David Russell Lawrence The Naturalist and his ‘Beautiful Islands’ Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific David Russell Lawrence Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Lawrence, David (David Russell), author. Title: The naturalist and his ‘beautiful islands’ : Charles Morris Woodford in the Western Pacific / David Russell Lawrence. ISBN: 9781925022032 (paperback) 9781925022025 (ebook) Subjects: Woodford, C. M., 1852-1927. Great Britain. Colonial Office--Officials and employees--Biography. Ethnology--Solomon Islands. Natural history--Solomon Islands. Colonial administrators--Solomon Islands--Biography. Solomon Islands--Description and travel. Dewey Number: 577.099593 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: Woodford and men at Aola on return from Natalava (PMBPhoto56-021; Woodford 1890: 144). Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgments . xi Note on the text . xiii Introduction . 1 1 . Charles Morris Woodford: Early life and education . 9 2. Pacific journeys . 25 3 . Commerce, trade and labour . 35 4 . A naturalist in the Solomon Islands . 63 5 . Liberalism, Imperialism and colonial expansion . 139 6 . The British Solomon Islands Protectorate: Colonialism without capital . 169 7 . Expansion of the Protectorate 1898–1900 . -

Species-Edition-Melanesian-Geo.Pdf

Nature Melanesian www.melanesiangeo.com Geo Tranquility 6 14 18 24 34 66 72 74 82 6 Herping the final frontier 42 Seahabitats and dugongs in the Lau Lagoon 10 Community-based response to protecting biodiversity in East 46 Herping the sunset islands Kwaio, Solomon Islands 50 Freshwater secrets Ocean 14 Leatherback turtle community monitoring 54 Freshwater hidden treasures 18 Monkey-faced bats and flying foxes 58 Choiseul Island: A biogeographic in the Western Solomon Islands stepping-stone for reptiles and amphibians of the Solomon Islands 22 The diversity and resilience of flying foxes to logging 64 Conservation Development 24 Feasibility studies for conserving 66 Chasing clouds Santa Cruz Ground-dove 72 Tetepare’s turtle rodeo and their 26 Network Building: Building a conservation effort network to meet local and national development aspirations in 74 Secrets of Tetepare Culture Western Province 76 Understanding plant & kastom 28 Local rangers undergo legal knowledge on Tetepare training 78 Grassroots approach to Marine 30 Propagation techniques for Tubi Management 34 Phantoms of the forest 82 Conservation in Solomon Islands: acts without actions 38 Choiseul Island: Protecting Mt Cover page The newly discovered Vangunu Maetambe to Kolombangara River Island endemic rat, Uromys vika. Image watershed credit: Velizar Simeonovski, Field Museum. wildernesssolomons.com WWW.MELANESIANGEO.COM | 3 Melanesian EDITORS NOTE Geo PRODUCTION TEAM Government Of Founder/Editor: Patrick Pikacha of the priority species listed in the Critical Ecosystem [email protected] Solomon Islands Hails Partnership Fund’s investment strategy for the East Assistant editor: Tamara Osborne Melanesian Islands. [email protected] Barana Community The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) Contributing editor: David Boseto [email protected] is designed to safeguard Earth’s most biologically rich Prepress layout: Patrick Pikacha Nature Park Initiative and threatened regions, known as biodiversity hotspots. -

ISSUE 71 Be the Captain of Your Own Ship

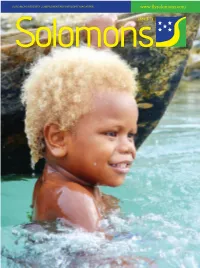

SOLOMON AIRLINE’S COMPLIMENTARY INFLIGHT MAGAZINE www.flysolomons.com SolomonsISSUE 71 be the captain of your own ship You are in good hands with AVIS To make a reservation, please contact: Ela Motors Honiara, Prince Philip Highway Ranadi, Honiara Phone: (677) 24180 or (677) 30314 Fax: (677) 30750 Email:[email protected] Web: www.avis.com Monday to Friday 8:00am to 5:00pm - Saturday – 8:00am to 12:00pm - Sunday – 8.00am to 12:00pm Solomons www.flysolomons.com WELKAM FRENS T o a l l o u r v a l u e d c u s t o m e r s Mifala hapi tumas fo wishim evriwan, Meri Xmas and Prosperous and Safe New Year Ron Sumsum Chief Executive Officer Partnerships WELKAM ABOARD - QANTAS; -our new codeshare partnership commenced Best reading ahead on the 15th November 2015. Includes the following- This is a major milestone for both carriers considering our history together now re-engaged. • Cultural Identity > the need to foster our cultures Together, Qantas and Solomon Airlines will service Australia with four (4) weekly services to and from Brisbane and one (1) service to Sydney • Love is in the Air > a great wedding story on the beautiful Papatura with the best connections within Australia and Trans-Tasman and Resort in Santa Isabel Domestically within Australia as well as Worldwide. This is a mega partnership from our small and friendly Hapi Isles. • The Lagoon Festival > the one Festival that should not be missed Furthermore, we expect to commence a renewed partnership with our annually Melanesian brothers in Air Vanuatu with whom we plan to commence our codeshare from Honiara to Port Vila and return each Saturday and • The Three Sisters Islands of Makira > with the Crocodile Whisperers Sunday each week. -

What Does an ASPRS Member Look Like? ± 25 M

movement known as Maasina Rule, which lasted from 1944 to 1952. Subsequently, in response to the worldwide STAND OUT FROM THE REST movement for decolonization, the Solomons set out on the path of constitutional development. The country was formally EARN ASPRS CERTIFICATION renamed Solomon Islands in 1975, and independence was attained on July 7, 1978” (Encyclopaedia Brittanica, 2014). ASPRS congratulates these recently Slightly smaller than Maryland, the Solomon Islands have Certified and Re-certified individuals: a coastline of 5,313 km, and its terrain is comprised of mostly rugged mountains with some low coral atolls. The lowest point CERTIFIED MAPPING SCIENTISTS is the Pacific Ocean (0 m), and the highest point is Mount REMOTE SENSING Popomanaseu (2,310 m) (World FactBook, 2014). Thanks to Mr. John W. Hager, the Astro Stations observed Paul Pope, Certification # RS217 in the Solomon Islands include: Cruz, at “Cruz Astro 1947,” Φ Effective April 8, 2014, expires April 8, 2019 o = 9° 25’ 27.61” S, Λo = 159° 59’ 10.14” E, αo = 99° 46’ 39.3” to Az. Mark from south, International ellipsoid , elevation = 2.20 feet. Reported under water, 23 Oct. 1961. Established by the 657th ASPRS Certification validates your professional practice Eng. Astro. Det. March 1947. and experience. It differentiates you from others in the CZ-X-6, Φo = 11° 34’ 13.3920” S, Λo = 166° 52’ 55.8300” profession. E, International ellipsoid, Ho = 10.5 feet. Area is Santa For more information on the ASPRS Certification program: Cruz Islands, Islands of Ndeni (Nendo), Utupua, Vanikoro (Vanikolo). I don’t know whether or not it includes the Reef contact [email protected] Islands. -

We, the Taumako Kinship Among Polynesians in the Santa Cruz Islands

WE, THE TAUMAKO KINSHIP AMONG POLYNESIANS IN THE SANTA CRUZ ISLANDS Richard Feinberg Kent State University Kent, Ohio USA [email protected] Raymond Firth’s We, The Tikopia, first published in 1936, still sets the standard for de- tailed, nuanced, sensitive ethnography. As Malinowski’s student, Firth—who died in 2002 at the age of 100—was a hard-headed functionalist, whose forte was careful exami- nation of cultural “institutions” and their effects on individuals as well as on other institutions. Suspicious of abstruse theoretical pronouncements, he presented his analy- ses in plain language and always situated them in relation to the “imponderabilia” of real people’s everyday lives. We, The Tikopia has been a foundational text for genera- tions of anthropologists, and it helped to guide my research on three Polynesian outliers over the past four decades. Since the time of Firth’s initial fieldwork, conditions in the region have changed drastically, as even the most remote communities have become en- meshed in the world market economy. In 2007-08, I studied a revival of indigenous voy- aging techniques on Taumako, a Polynesian community near Tikopia, in the southeastern Solomon Islands. I was struck by the extent to which the cash economy permeated Tau- mako life, altering the tone of kin relations in ways that would have been unimaginable on Tikopia in the 1920s—or even on Anuta, where I conducted research, in the 1970s. Here, I will examine Taumako kinship in light of the insights offered by Sir Raymond three quarters of a century ago and explore the changes to the kinship system brought about by new economic forces. -

Melanesia: Secrets 2017

Melanesia Secrets Solomon Islands and Vanuatu 20th to 31st October 2017 (12 days) Trip Report White-headed Fruit Dove by Stephan Lorenz Trip report compiled by Tour Leader, Stephan Lorenz Rockjumper Birding Tours | Melanesia www.rockjumperbirding.com Trip Report – RBL Melanesia - Secrets 2017 2 Tour Summary Starting in the Solomon Islands and finishing in Vanuatu, the cruise explored some true secrets of Melanesia, including visits to incredibly remote islands that harbour many seldom-seen endemics. In total, we covered about 1,200 nautical miles, visited 11 islands with more than a dozen landings, and recorded 118 species of birds, with several rare species of bats also noted. At sea, we enjoyed several hours of excellent pelagic birding. The tour started on Guadalcanal, where we spent a morning in the classic birding spot of Mt Austen, gathering up a fine selection of widespread Solomon endemics, plus a Black-headed Myzomela – a Guadalcanal endemic. From here, we cruised north overnight to land on the rarely-visited and even more rarely birded San Jorge Island, where we caught up with the endemic Solomons Cuckooshrike and White- billed Crow, both sought-after species. The following day, we landed on mysterious Malaita, which holds some of the most remote and inaccessible highland areas in the Solomons. We enjoyed a morning birding Nendo Flying Fox by Stephan Lorenz along an easily accessible logging track, where the very rare Red-vested Myzomela was the highlight of the morning. The island of Makira is home to several endemics, and we set forth finding a good number of them, with Makira Honeyeater, an endemic genus, especially memorable. -

Recommended Sicklebill Safaris Tours

Recommended Sicklebill Safaris Tours . TOUR 1: GUADALCANAL & RENNELL TOUR 5: GENTLE SOLOMONS he largest raised atoll in the world, Rennell is home to 43 species of breeding birds and boasts his tour visits most of the major hotspots in the Solomons with the exception of Santa Isabel. 6 endemics. All of the endemics can be seen in close proximity to the airfield by walking along It does however, limit itself to the areas that are most easily accessed and does not attempt the logging tracks. The tour also visits Honiara and its environs including a morning visit the more strenuous climbs up into the mountains. While it provides a very good representation Tto Mt Austen where Ultramarine Kingfisher, Duchess Lorikeet and White-billed Crow are amongst Tof Solomons birds, the more difficult montane birds, only found at high altitude, will not be seen. the highlights. A relatively easy tour with no steep treks up into the hills though the surface of the Rennell tracks can be a bit rough. TOUR 2: SANTA ISABEL BLACK-FACED PITTA HUNT TOUR 6: COMPREHENSIVE SOLOMONS ffering you the chance of some of the Solomon’s most Iconic birds - the Black-faced Pitta, his exciting birdwatching tour visits all the major birding sites within the Solomons in its the Fearful Owl and the Solomon’s Frogmouth, this is one of our most popular Solomons search for as many as possible of the islands endemics. It requires a good level of fitness as destinations. The walk up to Tiritonga is steep and needs a reasonable level of fitness but it is not an easy tour, with long steep hikes up into mountains, and nights camping under Othe rewards are great.