A Mathematical Analysis of Maria Valtorta's Mystical Writings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maria Valtorta Foundation Newsletter

MariaV altorta Viale Carducci, 71 - 55049 VIAREGGIO (Lucca) Newsletter www.fondazionemariavaltorta.it Edited by Fondazione Maria Valtorta – AUGUST 1, 2018 – Newsletter N° 51 PROBLEMS OF THE PRESENT TIME Father Migliorini, Maria Valtorta and Dora Barsottelli – part 1 Ordine Very little we know about Dora Barsottelli, but the little we know touches in a dei Servi di Maria dramatic way either Maria Valtorta and Father Migliorini. The fracture between Maria Valtorta and Father Migliorini, the definitive and irrevocable moving of him to Rome, the spiritual solitude of her; the rise and disappearance of Dora Barsottelli, are the happenings of our history. In that year 1946, finally freed from war, but full of perils and poverty, there takes place a real, truly human tragedy, that will hardly strike Maria Valtorta and her inner circle. Father Romualdo M. Migliorini, Order of Servants of Maria, in 1942 First of all I obviously feel indispensable to summarize all facts given by Maria became the spiritual director of Valtorta’s writings. A note from the administration of The Notebooks 1945-1950, the mystic Maria Valtorta until his removal and transfer from Viareg- tells who Dora Barsottelli was: gio to Rome, in 1946. Died July 10, «This refers to Dora Barsottelli, from Camaiore, Tuscany, who said she was favored 1953. by manifestations concerning whose origins yet, Maria Valtorta arbored apprehen- sion and doubt, as we shall see in the course of the present volume and as can be noted in other writings separate from the Notebooks. They both knew about each other because of Father Migliorini, spiritual director of Maria Valtorta was also Barsottelli’s care taker’s case». -

Maria Valtorta

Maria Valtorta THE BOOK OF AZARIAH Translated from the Italian by David G. Murray CENTRO EDITORIALE VALTORTIANO All rights reserved in all Countries. Original title: Libro di Azaria. @ 1972 by Tipografia Editrice M. Pisani. @ 1982 by Emilio Pisani. @ 1988 by Centro Editoriale Valtortiano srl. Translation by David G. Murray. @) 1993 by Centro Editoriale Valtortiano srl., Viale Piscicelli 89-91, 03036 Isola del Liri - Italy. ISBN 88-7987-013-0 Film setting by Centro Editoriale Valtortiano srl. Printing and Binding by Tipografia Editrice M. Pisani sas., Isola del Liri. Cover design by Piero Luigi Albery. Printed in Italy, 1993. CONTENTS 10 Translator's Note to the English Edition 12 Alphabetical Listing of Abbreviations for Citing the Books of the Bible 15 Sexagesima Sunday 19 Quinquagesima Sunday 23 The First Sunday of Lent 28 The Second Sunday of Lent 33 The Third Sunday of Lent 42 The Fourth Sunday of Lent 50 Passion Sunday 59 Palm Sunday 68 Resurrection Sunday 74 In Albis Sunday 83 Second Sunday after Easter 90 Third Sunday after Easter 98 Fourth Sunday after Easter 107 Fifth Sunday after Easter 116 Sunday within the Octave of the Ascension 6 124 Pentecost Sunday 133 Holy Mass of the First Sunday after Pentecost and Feast of the Holy Trinity 140 Corpus Christi 148 Holy Mass in the Octave of Corpus Christi 156 Sunday in the Octave of the Sacred Heart and commemoration of St. Paul 163 Fourth Sunday after Pentecost 172 Fifth Sunday after Pentecost 179 Sixth Sunday after Pentecost 182 Seventh Sunday after Pentecost 186 Eighth Sunday after -

Voiding the Voices of Heaven & the Anathema of Vatican I

VOIDING VOIDING TTHHEE VVOOIICCEESS OOFF HHEEAA VVEENN The Church’s Post Vatican Spiritual, Moral and Ecclesiastical Crisi s, The Poem of the Man-Go d and the New Evangelization © 2002 by David J. Webster, M. Div. VV OO II DD II NN GG TTHHEE VVOOIICCEESS OOFF HHEEAAVVEENN The Church’s Post Vatican II Spiritual, Moral and Ecclesiastical Crisis, The Poem of the Man-God and the New Evangelization TESTIMONIALS OF SUPPORT “Your point in this essay is valid, and indeed, it is the scandal of our time that . the Church is able to suppress . warnings from Heaven . excellent essay.” Stephen Foglein, Missionary of Our Lady of La Salette, Orangevale, CA and author of five books. “I enjoyed your paper on Private Revelation. It is well written.” Father Bill O’Neill, Pastor of Our Lady of Grace Church, Hinkley, OH. “He (the author) has tackled a problem that Fr. Gruner has often addressed.” Father Michael Jareski, Secretary for The Servants of Jesus and Mary at The Fatima Center, Constable, NY “Voiding the Voices of Heaven. I could not more wholeheartedly agree.” Father Alfred O. Winshman, S.J., Marian Renewal Ministry, Boston MA Enthusiastically endorsed by Rev. Frank Kenney, S.T.D., from Dayton, OH. Fr. Kenney holds a doctorate in Marian Theology. Additional copies available from: Save Our Church P.O. Box 1404 Medina OH 44050 Order Form available at our Bookstore Catalog at www.saveourchurch.org Table of Contents Dedication Introduction Chapter One: The Voices of Heaven – The Needed Acts of Heaven’s Mercy / Page 1 Do Not Allow My “Future Voices” to -

St Joseph His Life and Mission

St Joseph His Life and Mission John D Miller CONTENTS Introduction 2 The Annunciation 5 The Marriage of Joseph and Mary 6 A typical Jewish marriage 8 Joseph’s dilemma 10 The Nativity 12 The Circumcision and Naming of Jesus 12 The Presentation in the Temple 13 The Flight into Egypt 13 The Boy Jesus in the Temple 15 When did Joseph die? 17 The Holiness of Saint Joseph 19 The Cult of Saint Joseph 22 Conclusion 26 Bibliography 27 END NOTES 29 Copyright © John Desmond Miller 2017 ST JOSEPH HIS LIFE AND MISSION An Essay by John D Miller 2 Introduction Though prayers to Saint Joseph featured in my life I had never paid great attention to him. I had learnt the night prayer to Jesus, Mary and Joseph for assistance ‘in my last agony’ when at school aged eight. In later life I had developed the habit of asking St Joseph’s help with practical matters such as problems with the car or computer. It was a reference to St Joseph during an Advent retreat in December 2016 that prompted me to explore his life and mission in more detail. The retreat master mentioned two things about St Joseph which intrigued me: within the Holy Family Joseph held ‘a primacy of authority’ while Mary held ‘a primacy of love’1 and secondly that a recent mystic had experienced inner locutions from St Joseph indicating that he had been sanctified in the womb. A search of the Internet on Sister Ephrem Neuzil confirmed that St Joseph had reportedly said to her that he had been freed from original sin soon after his conception. -

Maria Valtorta Was Born in Caserta, Italy on March 14, 1897

In Response to Various Questions Regarding “The Poem of the Man-God" Published on April 15, 2006 by Dr. Mark Miravalle, Professor of theology and Mariology at Franciscan University of Steubenville. [Note: The Poem of the Man God has since been published under the title The Gospel as Revealed to Me, but they are the same book.] Maria Valtorta was born in Caserta, Italy on March 14, 1897. Deeply pious, Maria was strongly attracted to God from early childhood, but it was as a young woman that she started reporting mystical experiences. In 1920 she was randomly attacked by a young man who hit her in the back with an iron bar. Badly injured, she was bedridden for three months and her health began its gradual decline. In the years to follow she made a personal offering of her sufferings to the two Divine attributes of Love and Justice, and by April, 1934, she was permanently confined to her bed. It was in 1943 that Valtorta began to write down in her notebooks the “dictations,” the mystical visions and messages she reported receiving from Jesus and Mary, and the years between 1943 and 1947 were the period of her greatest output. She wrote almost 15000 pages of dictation, a little less than two-thirds of which comprised The Poem of the Man-God, a substantial work on the life of Jesus Christ beginning from the birth of Our Lady and ending at her Assumption. Maria Valtorta died on October 12, 1961. In 1973 her remains were moved to Florence and entombed in the Capitular Chapel in the Grand Cloister of the Basilica of the Most Holy Annunciation in Florence. -

Save Our Church Bookstore Catalog

SSaavvee OOuurr CChhuurrcchh BBooookkssttoorree CCaattaalloogg Materials Available on the Amsterdam Revelations given to Ida Peerdamen: wwww.ladyofallnations.orgww.ladyofallnations.org Materials Available on the Revelations to the children of Garabandal: wwww.garabandal.comww.garabandal.com OUR OWN published works on the Valtorta revelations on the next 12 pages! Order all Maria Valtorta’s works from wwww.valtorta.orgww.valtorta.org And please check out this incredible Valtorta website: wwww.bardstown.com/~brchrysww.bardstown.com/~brchrys Our BOOKSTORE ORDER FORM will be found at the end of this CATALOG. WWeellccoommee ttoo SSaavvee OOuurr CChhuurrcchh BBooookkssttoorree CCaattaalloogg New! Just Published! 5½x8½ the 180 pg paperback Pine Cone Press Edition! A Convert Speaks from his Heart to his Evangelical Fundamentalist Brothers in Christ BY DAVID J. WEBSTER, A FORMER FUNDAMENTAL BAPTIST PASTOR “Like a brilliant flash of light and understanding after years of darkness and confusion! Presents a hope for true unity among all Bible Believers!” “This book will leave most evangelicals speechless and with no real argument left.” A powerful personal testimony and an utterly convincing apologetic for the Faith! Covers the material shared on EWTN’ the Journey Home program! CHAPTER ONE The Dilemma of a Zealous Anti-Catholic CHAPTER TWO Clearing the Controversy over Biblical Salvation CHAPTER THREE Discovering our Final Authority: The Church and its Bible CHAPTER FOUR Removing My Mental Roadblocks CHAPTER FIVE Experiencing the Miracle of Mary CHAPTER SIX Discovering the Mystery of the Eucharist Anyone with a proper understanding of the Catholic faith will see that faith everywhere in Scripture- without a single exception! The King James Version of Scripture is used throughout this work. -

Mariav Altorta

MariaV altorta Viale Carducci, 71 - 55049 VIAREGGIO (Lucca) Newsletter www.fondazionemariavaltorta.it Edited by Fondazione Maria Valtorta — MAY 15, 2017 — Newsletter N° 24 PROBLEMS OF THE PRESENT TIME MARIA VALTORTA AND THE LIVING JESUS OF ST. FRANCIS OF ASSISI. I do not consider the apparitions of St. Francis of Assisi to Maria Valtorta (just thirty in 1944) and not even what he says, as for what it’s written on the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola. In other words, I do not want to linger miserably over the details. I just want to see if there is any global similarity, and if so, should it be so profound, among what Jesus was for St. Francis and what Maria Valtorta urges to be each reader toward Jesus, with her writings. Let us then try to understand “that” Jesus of Saint Francis. Yes, but first of This picture shows a nearly 30 years old all, let us get rid of those awful clues that films kept on submitting us about him. Maria Valtorta in Viareggio, They tried to make him look like a knowledgeable ecologist; a banal nature’s praiser; just before she finally got bedridden almost an ecumenical new agers,“ante litteram” without a doctrine system. St. Francis was not any of the above. Two authors in some ways very far away from each other, have arrived at the same conclusion. The first one is Father Raniero Cantalamessa of the Friar Minors, preacher of the Pontifical Household, and he writes like this: «It is on this text [testament of Saint Francis] that the historians are rightly PRAYER based on, but with a limit which is impossible to overcome for them. -

Parish Library

CALL NUMBER SUBJECT AUTHOR TITLE 241.6 Abortion Allison, Loraine Finding Peace after Abortion 241.6 Abortion Burke, Theresa Forbidden Grief: The Unspoken Pain of Abortion 241.6 Abortion Burnside, Thomas J. At the Foot of the Cross 241.6 Abortion Burtchaell, James Tunstead Rachel Weeping and Other Essays on Abortion 241.6 Abortion Condon, Guy Fatherhood Aborted 241.6 Abortion Coyle, C.T. Men and Abortion 241.6 Abortion Curro, Ellen Caring Enough to Help 241.6 Abortion DeCoursey, Drew Lifting the Veil of Choice: Defending Life 241.6 Abortion DeMarco, Donald In My Mother's Womb: The Catholic Church's Defense of Natural Life 241.6 Abortion Euteneuer, Thomas J. Demonic Abortion 241.6 Abortion Florczak-Seeman, Yvonne Time to Speak: A Healing Journal for Post-abortive Women 241.6 Abortion Gorman, Michael J. Abortion & the Early Church 241.6 Abortion Horak, Barbara Real Abortion Stories 241.6 Abortion Johnson, Abby Unplanned 241.6 Abortion Klusendorf, Scott Case for Life 241.6 Abortion Maestri, William Do Not Lose Hope 241.6 Abortion Masse, Sydna Her Choice to Heal: Finding Spiritual and Emotional Peace After Abortion 241.6 Abortion Morana, Janet Recall Abortion 241.6 Abortion Pavone, Frank Ending Abortion 241.6 Abortion Powell, John Abortion: The Silent Holocaust 241.6 Abortion Reardon, David C. Jericho Plan: Breaking DoWn the Walls Which Prevent Post- Abortion Healing 241.6 Abortion Reisser, Teri A Solitary SorroW: Finding Healing and Wholeness After Abortion 241.6 Abortion Rini, Suzanne Beyond Abortion: A Chronicle of Fetal EXperimentation 241.6 Abortion Santorum, Karen Letters to Gabriel 241.6 Abortion Terry, Randall Operation Rescue 241.6 Abortion Willke, J.C. -

April 2021 of India and Community of Tamilnadu Church at St

Archbishop’s Engagements THE VOICE OF THE PASTOR Dear Fathers, Brothers and Sisters, 01 Thu E Mass of the Lord’s Supper, St. Mary’s Cathedral, Madurai The Leaders of Israel were called 02 Fri E Good Friday Service, St. Joseph’s Church, shepherds in the Old Testament (cfr. Ezek.34). In Gnanaolivupuram the New Testament Jesus calls himself as the Good Shepherd (John 10:11). In the gospel of Mark 03 Sat E Easter Vigil, St. Mary’s Cathedral, Madurai Jesus refers to his listeners as “Sheep without a 05 Mon M Month’s Mind Mass, Kavirayapuram Shepherd” (cfr. MK: 6:34). 07 Wed E Sacerdotal Ordination, Ofm Cap. Thirumangalam Jesus portrays himself not only as a shepherd but also as the gate. Hence he says “I 08 Thu E Releasing of the Book, Gnanolivupuram am the gate, whoever enters by me will be saved 11 Sun M Mass and Blessing of the Flag Pole, Periyakulam and will come in and go out and find pasture (Jn 10:9). By calling himself as the gate he points to us that he is the only source of salvation and we 12 Mon E Golden Jubilee Mass, Sivagangai are invited to find our way to him so that we may be on the safe path and 13 Tue M Archdiocesan Consult Meet, Archbishop’s House find fullness of life. Because he came that we may have life and have it in its fullness (cfr. John 10:10). This is confirmed by the saying of Jesus 14 Wed Legal Cell, Chennai where he says “I am the way and the truth and the life” (Jn 14:6). -

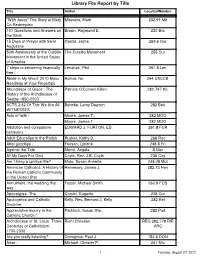

Library File Report by Title

Library File Report by Title Title Author LocalCallNumber "With Jesus" The Story of Mary Miravalle, Mark 232.91 Mir Co-Redemptrix 101 Questions and Answers on Brown, Raymond E. 220 Bro the Bible 15 Days of Prayer with Saint Garcia, Jaime 269.6 Gar Augustine 50th Anniversary of the Cursillo The Cursillo Movement 255 Cur Movement in the United States of America 7 steps to becoming financially Lenahan, Phil. 261.8 Len free : Abide in My Word: 2010 Mass Author, No 264 USCCB Readings at Your Fingertips Abundance of Grace : The Patricia O'Connell Killen 282.797 KIL History of the Archdiocese of Seattle 1850-2000 ACTS 2:32 Of This We Are All Behnke, Leroy Deacon 282 Beh WITNESSES Acts of faith : Moore, James T., 282 MOO Moore, James T., 282 MOO Addiction and compulsive EDWARD J. FURTON, ED. 261.8 FUR behaviors : Adult Education in the Parish Rucker, Kathy D. 268 Ruc After goodbye : Friesen, Lynette. 248.8 Fri Against the Tide Merici, Angela B Mer All My Days For God Coyle, Rev. J.B. Coyle 235 Coy Am I living a spiritual life? : Muto, Susan Annette. 248.48 Mut American Catholics: A History of Hennesey, James J. 282.73 Hen the Roman Catholic Community in the United Stat Annulment, the wedding that Foster, Michael Smith. 262.9 FOS was : Apocalypse, The Corsini, Eugenio 228 Cor Apologetics and Catholic Kelly, Rev. Bernard J. Kelly 282 Kel Doctrine Appreciative inquiry in the Paddock, Susan Star. 282 Pad Catholic Church / Archdiocese of St. Louis: Three Riehl,Christian REG 282.778 RIE Centuries of Catholicism, ARC 1700-2000 Are you really listening? : Donoghue, Paul J. -

Anthony PILLARI.Pdf

The Current Juridic and Moral Value of the Index of Forbidden Books by Anthony PILLARI DCA 6395 Chad GLENDINNING Faculty of Canon Law Saint Paul University Ottawa 2017 The author hereby authorizes Saint Paul University, its successors and assignees, to electronically distribute or reproduce this seminar paper by photography or photocopy, and to lend or sell such reproductions at a cost to libraries and to scholars requesting them. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 1 – HISTORY OF THE INDEX OF FORBIDDEN BOOKS ............................................. 7 1.1 Early Church History .............................................................................................................................. 7 1.2 Sacred Congregation of the Index (1571 – 1917)................................................................................. 10 1.3 Censorship in the 1917 Code ................................................................................................................ 13 CHAPTER 2 – ABROGATION OF THE INDEX: CURRENT JURIDIC AND MORAL STATUS .. .................................................................................................................................................................... 18 2.1 Abrogation of the Index ........................................................................................................................ 18 2.2 Current Juridic Status -

Survey of Recent Mariology Eamon R

Marian Studies Volume 53 The Marian Dimension of the Christian Article 12 Life: II. The Middle Period 2002 Survey of Recent Mariology Eamon R. Carroll Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Carroll, Eamon R. (2002) "Survey of Recent Mariology," Marian Studies: Vol. 53, Article 12. Available at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/marian_studies/vol53/iss1/12 This Back Matter is brought to you for free and open access by the Marian Library Publications at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Studies by an authorized editor of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Carroll: Survey of Recent Mariology A SURVEY OF RECENT MARIOLOGY (2002) Eamon R. Carroll, O.Carm. * As is the custom in this survey, three special items lead off, without prejudice to the scores of other books and articles that follow. The three represent pilgrimage shrines, the rosary and scripture. The ftrst entry I touched on last year, but it deserves this longer appreciation: The Madonnas of Europe: Pilgrim ages to the Great Marian Shrines of Europe (Ignatius Press, San Francisco, 2000, 288 pp.). Coffee-table size, this beautiful hardbound book contains the onsite photographs of seventy shrines taken over ftve years byJanusz Rosikon (famous for Soli darity coverage), with text by Wojciech Nizynski. The Polish primate Cardinal J 6zef Glemp and Cardinal Deskur contribute introductions, as does Norman Davies of Oxford. William M. McLoughlin, O.S.M., was consultant for the English translation. The seventy shrines run, in the British edition, "from the At lantic to the Urals and are divided into eight somewhat arbi trary units.