An Economic Analysis on Spatial Integration of Regional Rice Markets in Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ruwanwella) Mrs

Lady Members First State Council (1931 - 1935) Mrs. Adline Molamure by-election (Ruwanwella) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu by-election (Colombo North) (Mrs. Molamure was the first woman to be elected to the Legislature) Second State Council (1936 - 1947) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu (Colombo North) First Parliament (House of Representatives) (1947 - 1952) Mrs. Florence Senanayake (Kiriella) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena by-election (Avissawella) Mrs. Tamara Kumari Illangaratne by-election (Kandy) Second Parliament (House of (1952 - 1956) Representatives) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Avissawella) Mrs. Doreen Wickremasinghe (Akuressa) Third Parliament (House of Representatives) (1956 - 1959) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Colombo North) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Kiriella) Mrs. Vimala Wijewardene (Mirigama) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna by-election (Welimada) Lady Members Fourth Parliament (House of (March - April 1960) Representatives) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Fifth Parliament (House of Representatives) (July 1960 - 1964) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene by-election (Borella) Sixth Parliament (House of Representatives) (1965 - 1970) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Leticia Rajapakse by-election (Dodangaslanda) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte by-election (Balangoda) Seventh Parliament (House of (1970 - 1972) / (1972 - 1977) Representatives) & First National State Assembly Mrs. Kusala Abhayavardhana (Borella) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Dehiwala - Mt.Lavinia) Lady Members Mrs. Tamara Kumari Ilangaratne (Galagedera) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte (Balangoda) Second National State Assembly & First (1977 - 1978) / (1978 - 1989) Parliament of the D.S.R. of Sri Lanka Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Miss. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Evaluation of Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Assistance

Evaluation Working Paper Sri Lanka Country Assistance Program Evaluation: Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Assistance Evaluation August 2007 Supplementary Appendix E Operations Evaluation Department CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 27 April 2007) Currency Unit — Sri Lanka rupee (SLR) SLR1.00 = $0.0092 $1.00 = SLR109.27 ABBREVIATIONS ADB — Asian Development Bank EIRR — economic internal rate of return m3 — cubic meter MDG — Millennium Development Goal NWSDB — National Water Supply and Drainage Board TA — technical assistance UNDP — United Nations Development Programme USAID — United States Agency for International Development NOTE In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. Director General Bruce Murray, Operations Evaluation Department (OED) Director R. Keith Leonard, Operations Evaluation Division 1, OED Evaluation Team Leader Njoman Bestari, Principal Evaluation Specialist Operations Evaluation Division 1, OED Operations Evaluation Department CONTENTS Page Map ii A. Scope and Purpose 1 B. Sector Context 1 C. The Country Sector Strategy and Program of ADB 8 1. ADB’s Sector Strategies in the Country 8 2. ADB’s Sector Assistance Program 12 D. Assessment of ADB’s Sector Strategy and Assistance Program 16 E. ADB’s Performance in the Sector 20 F. Identified Lessons 21 G. Future Challenges and Opportunities 23 Appendix Positioning/Coherence of Asian Development Bank’s Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Strategies in Sri Lanka 24 Njoman Bestari (team leader, principal evaluation specialist) and Jennifer Simon (consultant, evaluation research associate) prepared this evaluation working paper. Caren Joy Mongcopa (senior operations evaluation assistant) provided administrative and research assistance to the evaluation team. The guidelines formally adopted by the Operations Evaluation Department (OED) on avoiding conflict of interest in its independent evaluations were observed in the preparation of this report. -

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details District Divisional Secretariat Divisional Secretary Assistant Divisional Secretary Life Location Telephone Mobile Code Name E-mail Address Telephone Fax Name Telephone Mobile Number Name Number 5-2 Ampara Ampara Addalaichenai [email protected] Addalaichenai 0672277336 0672279213 J Liyakath Ali 0672055336 0778512717 0672277452 Mr.MAC.Ahamed Naseel 0779805066 Ampara Ampara [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dammarathana Road,Indrasarapura,Ampara 0632223435 0632223004 Mr.H.S.N. De Z.Siriwardana 0632223495 0718010121 063-2222351 Vacant Vacant Ampara Sammanthurai [email protected] Sammanthurai 0672260236 0672261124 Mr. S.L.M. Hanifa 0672260236 0716829843 0672260293 Mr.MM.Aseek 0777123453 Ampara Kalmunai (South) [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Kalmunai 0672229236 0672229380 Mr.M.M.Nazeer 0672229236 0772710361 0672224430 Vacant - Ampara Padiyathalawa [email protected] Divisional Secretariat Padiyathalawa 0632246035 0632246190 R.M.N.Wijayathunga 0632246045 0718480734 0632050856 W.Wimansa Senewirathna 0712508960 Ampara Sainthamarathu [email protected] Main Street Sainthamaruthu 0672221890 0672221890 Mr. I.M.Rikas 0752800852 0672056490 I.M Rikas 0777994493 Ampara Dehiattakandiya [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dehiattakandiya. 027-2250167 027-2250197 Mr.R.M.N.C.Hemakumara 027-2250177 0701287125 027-2250081 Mr.S.Partheepan 0714314324 Ampara Navithanvelly [email protected] Divisional secretariat, Navithanveli, Amparai 0672224580 0672223256 MR S.RANGANATHAN 0672223256 0776701027 0672056885 MR N.NAVANEETHARAJAH 0777065410 0718430744/0 Ampara Akkaraipattu [email protected] Main Street, Divisional Secretariat- Akkaraipattu 067 22 77 380 067 22 800 41 M.S.Mohmaed Razzan 067 2277236 765527050 - Mrs. A.K. Roshin Thaj 774659595 Ampara Ninthavur Nintavur Main Street, Nintavur 0672250036 0672250036 Mr. T.M.M. -

REISEABLAUF 5 Tage / 4 Nächte Negombo – Dambulla – Sigiriya – Minneriya – Kandy – Nuwara Eliya – Negombo

REISEABLAUF 5 Tage / 4 Nächte Negombo – Dambulla – Sigiriya – Minneriya – Kandy – Nuwara Eliya – Negombo Day 01: Negombo – Dambulla Pick up from the hotel at Negombo at 0900hrs. Thereafter, travel to Dambulla. Upon arrival to Dambulla, visit the Golden Temple at Dambulla. Dambulla Cave Temples, vast isolated rock mass 500 feet high and a mile around the base. Here is found the famous Rock Temple dating to the First Century B.C. The caves of Dambulla sheltered King Walagamba during his 14 years of exile from Anuradhapura. When he regained the throne he built the most magnificent of Rock Temples to be found in the Island. Thereafter check-in to the hotel for dinner and overnight stay. Day 02: Dambulla – Sigiriya – Minneriya – Dambulla Breakfast at the hotel and travel to Sigiriya. Visit the very impressive 5th century Sigiriya Rock Fortress. This world heritage site, consists of the remains of a palace on the top of the rock, a mid-level terrace that includes the Lion Gate and the mirror wall with its frescoes of the 'Heavenly Maidens', the lower palace on the slopes below the rock, and the moats, walls and water gardens that extend for some hundreds of metres out from the base. Thereafter travel to Minneriya for the National Park safari. Located between Habarana and Polonnaruwa, the 8,890 hectares of Minneriya National Park consists of mixed evergreen forest and scrub areas and is home to favorites such as sambar deer, leopards and elephants. However the central feature of the park is the ancient Minneriya Tank (built in 3rd century AD by King Mahasena). -

Evaluation of Agriculture and Natural Resources Sector in Sri Lanka

Evaluation Working Paper Sri Lanka Country Assistance Program Evaluation: Agriculture and Natural Resources Sector Assistance Evaluation August 2007 Supplementary Appendix A Operations Evaluation Department CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 01 August 2007) Currency Unit — Sri Lanka rupee (SLR) SLR1.00 = $0.0089 $1.00 = SLR111.78 ABBREVIATIONS ADB — Asian Development Bank GDP — gross domestic product ha — hectare kg — kilogram TA — technical assistance UNDP — United Nations Development Programme NOTE In this report, “$” refers to US dollars. Director General Bruce Murray, Operations Evaluation Department (OED) Director R. Keith Leonard, Operations Evaluation Division 1, OED Evaluation Team Leader Njoman Bestari, Principal Evaluation Specialist Operations Evaluation Division 1, OED Operations Evaluation Department CONTENTS Page Maps ii A. Scope and Purpose 1 B. Sector Context 1 C. The Country Sector Strategy and Program of ADB 11 1. ADB’s Sector Strategies in the Country 11 2. ADB’s Sector Assistance Program 15 D. Assessment of ADB’s Sector Strategy and Assistance Program 19 E. ADB’s Performance in the Sector 27 F. Identified Lessons 28 1. Major Lessons 28 2. Other Lessons 29 G. Future Challenges and Opportunities 30 Appendix Positioning of ADB’s Agriculture and Natural Resources Sector Strategies in Sri Lanka 33 Njoman Bestari (team leader, principal evaluation specialist), Alvin C. Morales (evaluation officer), and Brenda Katon (consultant, evaluation research associate) prepared this evaluation working paper. Caren Joy Mongcopa (senior operations evaluation assistant) provided administrative and research assistance to the evaluation team. The guidelines formally adopted by the Operations Evaluation Department (OED) on avoiding conflict of interest in its independent evaluations were observed in the preparation of this report. -

OATLAND by JETWING No. 124, St. Andrew's Drive, Nuwara Eliya, Sri

OATLAND BY JETWING No. 124, St. Andrew’s Drive, Nuwara Eliya, Sri Lanka Reservations: +94 11 4709400 Bungalow: + 94 52 222 2445, +94 52 222 2572 Fax: +94 11 2345729 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.jetwinghotels.com General Manager: Mr. Upul Leukebandara 1. INTRODUCTION Oatland by Jetwing sits 6,200 feet above sea level cradled amidst the mist covered highlands of Nuwara Eliya. This colonial bungalow preserves the charm of a bygone era with an ambience that exudes its own exquisite character while offering guests the non-hotel, private house experience. 2. LOCATION The drive up to the Oatland by Jetwing is a scenic one, with lush greenery, waterfalls, tea plantations and majestic mountains. It is approximately 170 km (5 hours) from the Bandaranaike International Airport. It is just a short stroll away from Nuwara Eliya City and Jetwing St. Andrew’s. 3. ROOMS The rooms at Oatland by Jetwing boast modern facilities with colonial architecture. Discover the charms of traditional bed chambers. 3.1 Total Number of Room ROOMS UNITS AREA Room - 20.2 sq.m. Deluxe 04 Bathroom - 5.7 sq.m. Total – 25.9 sq.m. 3.2 Room Facilities • Individual heating units • Bathroom with shower and hot and cold water • Electric power – 220v to 240v • Tea and coffee making facility • Bottled water • Electronic safe • Hair dryer • Iron and ironing board • Telephone 3.3 Room Facilities on Request • Baby cots 4. DINING There is a host of dining experiences at Oatland by Jetwing which includes a 20 sq.m. dining room as well as an al fresco dining area in the garden. -

PA Circular 3-2019 English.Pdf

Public Administration Circular : 03/2019 My No : EST-3/DICIP/06/0249 (i) Ministry of Public Administration and Disaster Management Independence Square Colombo 07. 20.02.2019 Secretaries to Ministries Chief Secretaries of Provinces Heads of Departments List of Names of Disciplinary Inquiry Officers under Sub Section 19:5, Chapter XLVIII, Volume II of the Establishments Code This circular is issued with the inclusion of the list of names of disciplinary inquiry officers who were registered in the Public Administration Circulars from 31/2001 up to 31/2001(XIV) containing the list of names of the disciplinary inquiry officers updated by this Ministry as per the provisions in sub section 19:5, Chapter XLVIII, Volume II of the Establishments Code and further have exercised their consent to remain in the pool of disciplinary inquiry officers. 02. Accordingly, the Public Administration Circulars from 31/2001 up to 31/2001(XIV) are hereby cancelled without prejudice to the formal disciplinary inquiries already commenced as per the list of names of Disciplinary Officers declared by the said Circulars, with the effective date of this Circular and hereinafter only the list of names of disciplinary inquiry officers declared by Schedule 01 of this Circular shall be applied. 03. However, the Attorneys at Law, whose names are indicated in the list of names of the disciplinary officers issued by Public Administration Circular 35/92(II) dated 26.06.1995 and 35/92(IV) dated 13.11.1997 can act further as disciplinary inquiry officers. 04. However, the disciplinary inquiry officers cannot act as prosecuting or defending officers at the instances specified by sub section 19:14, Chapter XLVIII, Volume II of the Establishments Code. -

2. Introduction to Kurunegala Area : 2.1 Location and History : 2.2

2. Introduction to Kurunegala Area : 2.1 Location and History : Kurunegala town is the capital of Kurunegala district as well as the capital of North Western Province (Fig 2.1). It has been administered by a Municipal council from as early as 1952 and is yet the only Municipality in the province. It is located at the 98 km post along the Ambepussa - Kurunegala - Trincomalee road in the North - East direction of Colombo. Total area of the district is 4,813 sq. km and this is the third biggest district in Sri Lanka. It is connected with middle hill (Kandy.Matale) in East and low land (Puttalam,Chilaw) of above 100 ft in West. The district is situated 100ft - 500ft above sea level. However to the East of the city it is 500ft - 1000ft. Climate in this district can be classified into three zones. Western and Northern part is in dry zone. Central area is with medium weather and southern zone is with wet weather. Kurunegala had the ancient kingdoms such as Yapahuwa and Panduwasnuwara. Kurunegala is located within the "Coconut Triangle" and most of the service activities related to the coconut plantation sector are located in this town. 2.2 Regional Aspects : Kurunegala is located in North - Western Province and is predominantly an agricultural area. Coconut and paddy are the major agricultural crops. It has access to Northern, Eastern, Central and Western provinces. It is surrounded by Puttalam, Anuradhapura, Matale, Kandy, Kegalle and Gampaha districts. It has a road network connected to many parts of the country.(Fig 2.2) They are, 1. -

Spatial Variability of Rainfall Trends in Sri Lanka from 1989 to 2019 As an Indication of Climate Change

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Spatial Variability of Rainfall Trends in Sri Lanka from 1989 to 2019 as an Indication of Climate Change Niranga Alahacoon 1,2,* and Mahesh Edirisinghe 1 1 Department of Physics, University of Colombo, Colombo 00300, Sri Lanka; [email protected] 2 International Water Management Institute (IWMI), 127, Sunil Mawatha, Pelawatte, Colombo 10120, Sri Lanka * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Analysis of long-term rainfall trends provides a wealth of information on effective crop planning and water resource management, and a better understanding of climate variability over time. This study reveals the spatial variability of rainfall trends in Sri Lanka from 1989 to 2019 as an indication of climate change. The exclusivity of the study is the use of rainfall data that provide spatial variability instead of the traditional location-based approach. Henceforth, daily rainfall data available at Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation corrected with stations (CHIRPS) data were used for this study. The geographic information system (GIS) is used to perform spatial data analysis on both vector and raster data. Sen’s slope estimator and the Mann–Kendall (M–K) test are used to investigate the trends in annual and seasonal rainfall throughout all districts and climatic zones of Sri Lanka. The most important thing reflected in this study is that there has been a significant increase in annual rainfall from 1989 to 2019 in all climatic zones (wet, dry, intermediate, and Semi-arid) of Sri Lanka. The maximum increase is recorded in the wet zone and the minimum increase is in the semi-arid zone. -

Classic Sri Lanka

Classic Sri Lanka Classic Sri Lanka 9 Days | Starts/Ends: Colombo PRIVATE TOUR: Exotic Sri Lanka, • 8 nights SUPERIOR hotels. STANDARD Day 2 : Sightseeing in ancient cities steeped in history, and DELUXE hotel options are also Colombo available upon request. Accommodation elephants, tea plantations, lush Today, your guide will take you on a driving rating – See Trip Notes for details countryside, bustling bazaars and tour around colourful Colombo, Sri Lanka's • Touring - Colombo, Dambulla, frenetic capital. Just off the north end of wildlife, Sri Lanka has all this and Polonnaruwa, Sigariya, Matale, Kandy, Galle Road, the main north-south artery of more. Enjoy a wonderful 9 day Nuwara Eliya and Udawalawe NP the city is the area known as the Fort, once • Jeep safari/game drive in Udawalawe holiday taking in the highlights of a colonial stronghold but now the site of National park this enchanting island. many government buildings and interesting • Escorted by a licensed English speaking shops. Just south of the Fort is Galle Face chauffeur guide HIGHLIGHTS AND INCLUSIONS Green, a seaside expanse where informal • An airport arrival transfer day 1 and a cricket games are played out amongst city departure transfer day 9 Trip Highlights folk enjoying a pleasant stroll. At the south • All transfers and transportation in private end of the green is the Galle Face Hotel, a • Polonnaruwa - 11th century city air-conditioned tourism vehicles beautiful colonial-era hotel. Just east of the • Sigiriya - Spectacular 5th century fortress • Specialist local guides at some sites Fort is the Pettah, the traditional bazaar district ruins • Entrance fees to all included sites – a colourful retail experience. -

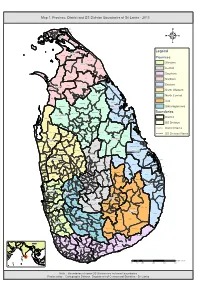

Map 1: Province, District and DS Division Boundaries of Sri Lanka - 2013

Map 1: Province, District and DS Division Boundaries of Sri Lanka - 2013 Vadam aradchi North (P oint Pedro) Valikam am North (Tellipallai) Valikam am S outh- West ( Sandilipay ) Vadam aradchi South-W es t (K araveddy) Valikam am W est (Chankanai) Karainagar Valikam am E ast (K opay) Valikam am S outh ( Uduv il) Jaffna Is land North (K ayts ) Thenm aradchi (Chavak achcheri) Jaffna Nallur Is land S outh (V elanai) Vadam aradchi Eas t Pachc hilaipalli 4 Delft Kandavalai Legend Kilinochchi Poonakary Karac hchi Provinces Puthukk udiyiruppu Mullaitivu Western Thunuk kai Maritim epattu Oddus uddan Central Mannar Town Southern Manthai W es t Manthai E ast Vav uniy a Nor th Welioya Northern Padavi Sr i P ura Madhu Eastern Mannar Vavuniya Padaviya Nanattan Vav uniy a Kuchc haveli North Western Vav uniy a S outh Gom ar ank adawala Kebithigollewa North Central Mus ali Vengalacheddik ulam Uva Morawewa Medawachc hiya Tr inc omalee Town and Gr av ets Mahawilachc hiy a Trincomalee Hor owpothana Sabaragamuwa Tham balagam uwa Ram bewa Kahatagas digiliya Kinniya Muttur Nuwar agam Palatha Central Boundaries Anuradhapura Mihinthale Kanthale Vanathawilluwa Noc hchiyagama District Nuwar agam Palatha E ast Seruv ila Verugal (E achc hilam pattu) Galenbindunuwewa Nac hchaduwa DS Division Thirappane Thalawa Medirigiriya Rajanganay a Colombo Tham buttegam a District Name Karuwalagas wewa Gir ibawa Hingurakgoda Ipalogam a Palugas wewa Kolonnawa Lank apura DS Division Name Welikanda Koralai P attu North (V aharai) Puttalam Galnewa Nawagattegam a Galgam uwa Kekirawa