Timber! Michigan Time Traveler Teacher's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forestry Books, 1820-1945

WASHINGTON STATE FORESTRY BIBLIOGRAPHY: BOOKS, 1820‐1945 (334 titles) WASHINGTON STATE FORESTRY BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS (published between 1820‐1945) 334 titles Overview This bibliography was created by the University of Washington Libraries as part of the Preserving the History of U.S. Agriculture and Rural Life Grant Project funded and supported by the National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH), Cornell University, the United States Agricultural Information Network (USAIN), and other land‐grant universities. Please note that this bibliography only covers titles published between 1820 and 1945. It excludes federal publications; articles or individual numbers from serials; manuscripts and archival materials; and maps. More information about the creation and organization of this bibliography, the other available bibliographies on Washington State agriculture, forestry, and fisheries, and the Preserving the History of U.S. Agriculture and Rural Life Grant Project for Washington State can be found at: http://www.lib.washington.edu/preservation/projects/WashAg/index.html Citation University of Washington Libraries (2005). Washington State Agricultural Bibliography. Retrieved from University of Washington Libraries Preservation Web site, http://www.lib.washington.edu/preservation/projects/WashAg/index.html © University of Washington Libraries, 2005, p. 1 WASHINGTON STATE FORESTRY BIBLIOGRAPHY: BOOKS, 1820‐1945 (334 titles) 1. After the War...Wood! s.l.: [1942]. (16 p.). 2. Cash crops from Washington woodlands. S.l.: s.n., 1940s. (30 p., ill. ; 22 cm.). 3. High‐ball. Portland, Ore.: 1900‐1988? (32 p. illus.). Note: "Logging camp humor." Other Title: Four L Lumber news. 4. I.W.W. case at Centralia; Montesano labor jury dares to tell the truth. Tacoma: 1920. -

Planting Power ... Formation in Portugal.Pdf

Promotoren: Dr. F. von Benda-Beckmann Hoogleraar in het recht, meer in het bijzonder het agrarisch recht van de niet-westerse gebieden. Ir. A. van Maaren Emeritus hoogleraar in de boshuishoudkunde. Preface The history of Portugal is, like that of many other countries in Europe, one of deforestation and reafforestation. Until the eighteenth century, the reclamation of land for agriculture, the expansion of animal husbandry (often on communal grazing grounds or baldios), and the increased demand for wood and timber resulted in the gradual disappearance of forests and woodlands. This tendency was reversed only in the nineteenth century, when planting of trees became a scientifically guided and often government-sponsored activity. The reversal was due, on the one hand, to the increased economic value of timber (the market's "invisible hand" raised timber prices and made forest plantation economically attractive), and to the realization that deforestation had severe impacts on the environment. It was no accident that the idea of sustainability, so much in vogue today, was developed by early-nineteenth-century foresters. Such is the common perspective on forestry history in Europe and Portugal. Within this perspective, social phenomena are translated into abstract notions like agricultural expansion, the invisible hand of the market, and the public interest in sustainably-used natural environments. In such accounts, trees can become gifts from the gods to shelter, feed and warm the mortals (for an example, see: O Vilarealense, (Vila Real), 12 January 1961). However, a closer look makes it clear that such a detached account misses one key aspect: forests serve not only public, but also particular interests, and these particular interests correspond to specific social groups. -

Module Objective

Section I. Introduction and Basic Principles Module I. Analysis of the Global Ecological Situation Module Objective Aware of the global ecological situation and the importance to adopt practices and behaviors promoting the sustainable management and conservation of the natural resources. Introduction Our world is suffering unpredictable changes in the natural world. Everywhere, destruction and profound degradations of the natural habitats are found and their implications for biodiversity conservation and resources sustainability have global impact (1). Increasingly more, people of all disciplines – scientists, economists, business people and world leaders, along with professional environmental activists – recognize that our population’s habits are not sustainable. Because of these tendencies, we are on a collision course threatening not only our basic human needs, but also the fundamental systems that maintain the planet’s ability to support life (2). A finite planet cannot continue adding 90 million people each year to the global population, nor can we endure the loss of top soil, atmosphere changes, species extinction, and water loss without re- establishing sufficient resources levels in order to permit life support (2). The planet that we know today is very different from the planet that existed immediately after its start date. Approximately 4.5 billion years ago the world began. It was not affected by the appearance of human life. Within 200 thousand years, human beings evolved to act as the agent of change that sparked the many changes occurring in our planet’s natural habitats: threatened and extinct species and the deterioration of the air, water and soils of the Earth’s habitats. -

2018 Newsletter

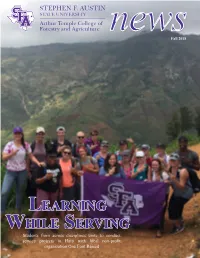

newsFall 2018 LEARNING WHILE SERVING Students from across disciplines unite to conduct service projects in Haiti with local non-profit organization One Foot Raised CONTENTS COLLEGE NEWS 4 ATCOFA enters partnership with Jilin Provincial Academy of Forestry Sciences 5 National Center for Pharmaceutical Crops receives patent 6 Dr. Craig Morton named Agriculture Educator of the Year ARTHUR TEMPLE 7 Resource Management Service offers new COLLEGE OF forestry scholarship FORESTRY AND AGRICULTURE 8 Spatial science program provides key imagery for local non-profit 9 Faculty, staff highlights Sarah Fuller, outreach coordinator 10 New ATCOFA faculty and [email protected] staff STUDENT NEWS 419 East College St. 12 Students receive first place at statewide GIS P.O. Box 6109, SFA Station forum Nacogdoches, TX 75962 13 Student chapter wins national championship (936) 468-3301 14 Top scholar named Office email: [email protected] 15 Sylvans win Southern Forestry Conclave Send photos to or news to: 16 Summer ‘18 internships [email protected] 18 Graduate Research FEATURE 20 Learning While Serving ALUMNI AFFAIRS 22 Alumni Spotlight 26 ATCOFA at a glance CONTENTS from the dean Dear ATCOFA alumni and friends, As the fall 2018 semester draws to 5 a close and the holidays approach, it is appropriate to reflect on the 13 opportunities and recent achievements of the ATCOFA faculty, staff and students. Dr. Craig Morton, professor of agriculture, and Dr. Kenneth Farrish, Arnold Distinguished Professor of forest soils, were honored for their sustained innovation in teaching. Research conducted by Dr. Chris Schalk, assistant professor of forest wildlife management, was featured in a recent issue of Texas Parks and Wildlife magazine. -

Sumter National Forest Revised Land and Resource Management Plan

Revised Land and Resource Management Plan United States Department of Agriculture Sumter National Forest Forest Service Southern Region Management Bulletin R8-MB 116A January 2004 Revised Land and Resource Management Plan Sumter National Forest Abbeville, Chester, Edgefield, Fairfield, Greenwood, Laurens, McCormick, Newberry, Oconee, Saluda, and Union Counties Responsible Agency: USDA–Forest Service Responsible Official: Robert Jacobs, Regional Forester USDA–Forest Service Southern Region 1720 Peachtree Road, NW Atlanta, GA 33067-9102 For Information Contact: Jerome Thomas, Forest Supervisor 4931 Broad River Road Columbia, SC 29212-3530 Telephone: (803) 561-4000 January 2004 The picnic shelter on the cover was originally named the Charles Suber Recreational Unit and was planned in 1936. The lake and picnic area including a shelter were built in 1938-1939. The original shelter was found inadequate and a modified model B-3500 shelter was constructed probably by the CCC from camp F-6 in 1941. The name of the recreation area was changed in 1956 to Molly’s Rock Picnic Area, which was the local unofficial name. The name originates from a sheltered place between and under two huge boulders once inhabited by an African- American woman named Molly. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, or marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). -

American Forestry"

AMERICAN FORESTRY" VOL. XXV JUNE, L919 NO. 306 THE AMERICAN LUMBERJACK IN FRANCE / BY LIEUT.-COL. W. B. GREELEY, 20m ENGINEERS OTHING illustrates the far-reaching economic de companies of forest and road engineer3, each 250 men mands of the Great 'Var more sharply than the strong, had been sent to France. The core of a 49th N enormous use of timber in almost every phase of Company was obtained subsequently from the New Eng military operations. From the plank roads at the front, land sawmill units which were sent to old England in the bomb proofs, the wire the early summer of 1917 entanglements, and the ties to cut lumber for the Brit needed for the rapid repair ish Government. These or construction of railroads troops represented every upon which military strate State in the Union. Prac gy largely depended, to the tically every for est r y h 0 5 pit al 5, warehouses, agency in' the country, to camps, and docks at the gether with many lumber base ports, timber was in companies and associations, constant demand as a mu took off their coats to help nition of war. One of the in obtaining the right type earliest requests for help of men. The road engi from the United States by neers of the United States both our French and Brit took hold of the organiza ish allies was for regiments tion of the twelve com of trained lumbermen. Gen panies of troops designed eral Pershing had been in for road construction in a France less than two similar spirit. -

TIMBER!TIMBER! Replaced

- . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - . - activity 11 Concept: With continued population growth, renewable resources, such as trees, are often used faster than they can be TIMBER!TIMBER! replaced. Objectives: Students will be able to: • Record and calculate the supply and demand of a natural resource. • Graph the supply and demand for Introduction: trees based on their calculations. People rely on wood from trees to heat their homes, cook their food, and provide build- • Explain the effect on a natural resource when demand exceeds ing materials and paper for homes, schools and businesses. The more people there are, supply. the greater the demand for wood. While it takes only seconds to cut down a tree, it takes • Contrast arithmetic growth with years to grow a new one. We also depend upon forests to regulate climate, clean air and geometric growth. water, conserve precious soil, and provide homes for many birds and animals. In almost Skills: every part of the world, trees are being cut down at a faster rate than they are being Calculating, graphing, working in replaced. The following simulation illustrates what happens to a given forest when the cooperative groups, interpreting data demand for tree products outstrips the supply. Method: In groups, students role-play a forest Procedure: management simulation and calculate the supply and demand for trees in a 1. Divide the class into groups of four students. For each group, assign the following fictitious forest. They record and graph roles: lumberjack, forest, forest manager, timer. their results. 2. Give 120 craft sticks in a coffee can to each student representing the forest. -

As the Piedmont Regional Forester and Also the Incident Commander

April 2018 As the Piedmont Regional Forester and also the Incident Commander (IC) of our Incident Management Team (IMT), I’d like to share some of what I have learned in my nearly 35 years with the Commission about how leadership opportunities can make each one of us the best March Fire Photos version of ourselves. Page 8 These thoughts reinforce several of our Our IMT is founded on the three new State Forester’s five overarching Wildland Fire Leadership Principles of goals, including providing a safe, Duty, Respect, and Integrity. Let’s look desirable and friendly workplace that at them and how each one can help us relies on good communications, which to be the best version of ourselves while results in outstanding customer service. striving for our goals. I believe that to be successful you must Duty – Be proficient in your job daily, set goals and then focus on the progress both technically and as a leader you make towards those goals. But one - Make sound and timely decisions must be able to measure that progress; Tree Farm Legislative Day - Ensure tasks are understood, Page 16 if you can’t measure it, you can’t change it. So as we make progress we should supervised, and accomplished celebrate those accomplishments. - Develop your subordinates for the This celebration of progress in the end future helps us to persevere towards those Respect - Know your subordinates and goals. Because as we sense that we are look out for their well-being making progress, we tend to be filled - Build the team with passion, energy, enthusiasm, purpose and gratitude. -

Dnr&Cooperating Foresters Serving Wisconsin Landowners

2018 DIRECTORY OF FORESTERS DNR & COOPERATING FORESTERS SERVING WISCONSIN LANDOWNERS WISCONSIN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF FORESTRY PUBLICATION FR-021-2018 The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources provides equal opportunities in its employment, programs, services, and functions under an Affirmative Action Plan. If you have any questions, please write to Equal Employment Opportunity Office, Department of Interior, Washington, D.C. 20240. This publication is available in alternative format upon request. Please call 608-264-6039 for more information. 2 2018 Directory of Foresters 2018 DIRECTORY OF FORESTERS The 2018 Directory of Foresters lists: • Foresters employed by the State of Wisconsin - Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) who provide professional advice and technical assistance to private forest landowners. • Private enterprise foresters (consulting foresters and industrial foresters) who have signed a Cooperating Forester Agreement with the Department; these foresters are called ‘Cooperating Foresters’. Cooperating Foresters who provide assistance to private forest landowners comply with DNR forest management standards found in statutes, administrative rules, Department handbooks and manual codes. Cooperating Foresters must attend annual continuing education courses and file periodic reports with the Department. • Other partners in the private forestry assistance network including the American Tree Farm System, Cooperative Development Services, University of Wisconsin Extension, Wisconsin Woodland Owners Association and Wisconsin Woodland Owner Cooperatives. • A regularly updated list of DNR & Cooperating Foresters is available at: dnr.wi.gov; use search keyword ‘forestry assistance locator’. IMPORTANT USER INFORMATION The Department of Natural Resources presents this Directory with no intended guarantee or endorsement of any particular private consulting Cooperating Forester, their qualifications, performance or the services they provide. -

SULLY DISTRICT 2017 Fall Camporee Oct 20-22, 2017 Camp Snyder, Haymarket

SULLY DISTRICT 2017 Fall Camporee Oct 20-22, 2017 Camp Snyder, Haymarket 1. EVENT INFORMATION and REGISTRATION The Sully District “Lumberjack” Camporee promises to be a great time. The event will include the opportunity for two nights of camping, starting Friday night, October 20, 2017. We encourage every Troop and Pack to participate – even if only for the Saturday day events. Axes, knives and saws are the tools of the trade for Boy Scouts. Participating Scouts should bring their enthusiasm and woodsman skills to the Lumberjack Camporee, for games, competition, and fellowship! DON’T FORGET YOUR TOTIN’ CHIP – it’s required to be able to participate! Your host for this Camporee is Sully District and Troop 7369. The Camporee Director is SM Michael Warsocki (571-212-2089) WHO is to attend: All Boy Scouts and Cub Scouts are welcome to attend. Camping is limited to Boy Scout Troops. Arrow of Light Cub Scouts may camp if they have a Troop sponsor. They will camp in the Troop area. All Cub Scouts are invited to visit for the day and are encouraged to stay for the Saturday evening campfire. WHERE: Camp William B. Snyder, 6100 Antioch Rd, Haymarket, VA In the Camporee Field (directions on page 7) WHEN: October 20-22, 2017 EVENTS: The Lumberjack Camporee will consist of these events: Skill Competitions and Food challenges Campfire and awards program PATCHES: Each registered person will receive a distinctive patch. COST: $20 per Boy Scout, Arrow of Light Cub or adult camping, $10 per Cub Scout or adult for Saturday activities. Cost includes the facility fees, Scout insurance, a Camporee patch, and materials for the various events. -

Hotshots: the Origins and Work Culture of America's Elite Wildland Firefighters

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 83 Number 3 Article 2 7-1-2008 Hotshots: The Origins and Work Culture of America's Elite Wildland Firefighters Lincoln Bramwell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Bramwell, Lincoln. "Hotshots: The Origins and Work Culture of America's Elite Wildland Firefighters." New Mexico Historical Review 83, 3 (2008). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol83/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hotshots THE ORIGINS AND WORK CULTURE OF AMERICA'S ELITE WILDLAND FIREFIGHTERS Lincoln Bramwell n a hot, dry day in early July 1994 near Glenwood Springs, Colorado, Ohigh winds fanned a small fire on the top of Storm King Mountain into a major conflagration that quickly blew over fifty-two ofthe U.S. Forest Service's most elite firefighters as they battled the flames. Fourteen men and women died, including nine members of the Prineville (Oregon) Hotshots. This tragedy brought national attention to Interagency Hotshot Crews (IHC), the backbone of the federal government's response to wildland fire. IHCs, twenty-person rapid-response fire crews, specialize in large, dangerous wild fires. Their high level of physical fitness, training, self-reliance, and exper tise make the IHC the Forest Service's elite firefighters; these men and women are dispatched to the worst fires in the toughest terrain under the most life-threatening circumstances. -

Warden and Woodsman

SD 12. / Ly,ryva/T1 [xT^tr^ ' 14 I RHODE ISLAND DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY. Warden and Woodsman. BY JESSE B. MOWRY Commissioner of Forestry* PROVIDENCE, R. I. E. L. KREEMAN COMPANY, STATE PRINTERS. 1913. RHODE ISLAND, ; DEPARTMENT .OF FORESTRY. WARDEN AND WOODSMAN. JESSE B. MOWRY, Commissioner of Forestry. PROVIDENCE, R. I. K. L. FREEMAN COMPANY, STATE PRINTERS. 1913. .R FOREWORD. Since progress in practical forestry depends much upon mutual understanding and assistance between the wardens, woodsmen, and timber owners, the aim in this pamphlet is to combine instructions to forest wardens with a brief outline of the best methods of cutting the timber of this region. The Author. Chepachet, November, 1913. MAR 28 W* PART L INSTRUCTIONS TO FOREST WARDENS. 1. The prevention of forest fires being a service of great value to the state, do not hesitate to do your full duty under the law, feel- ing assured in the discharge of your official duties of the support of all good citizens. 2. Read carefully the forest fire laws, which for convenience, are published in a booklet issued by this office. In reading the law you will observe that there are no restrictions whatever upon the setting of fires in the open air between December 1 and March 1. Between these two dates fires may be set anywhere without a permit from the warden. From March 1 to December 1 fires can be set without a permit, in plowed fields and gardens, and on other land devoid of inflammable materials, and on highways by owners of adjacent lands, etc.