Journal Volume 19, June-July 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bihar Military Police (BMP

FORM 1 (I) Basic Information Sl.No. Item Details 1. Name of the project/s-Bihar Military Police (B.M.P- Bihar Govt. Project 12)Supaul 2. S.No. in the schedule 3. Proposed capacity /area/length/tonnage to be Plot area=283382 sq.m handled/command area/lease area/number of wells to be TotalBuilt up drilled. area=31190.65sq.m 4. New/Expansion/Modernization NEW 5. Existing Capacity/Area etc. NIL 6. Category of Project i.e. ‘A’ or ‘B’ B 7. Does it attract the general condition? If yes, please specify. NO 8. Does it attract the specific condition? If yes, please specify. YES 9. Location - Supaul Thana no.-1 Plot/Survey/Khasra No. Khata no.-339 Village - Birpur Kesra no.-1020 Tehsil- BASHAANTPUR District SUPAUL,MAUJA-BHIMNAGAR State - BIHAR 10. Nearest railway station/airport along with distance in kms. 32kmRadhupur ( railway station) 11. Nearest Town, city, district Headquarters along with 62 km. Supaul Head Quarter distance in kms. 12. Village Panchayats, Zilla Parishad, Municipal Corporation, Birpur,Bhimnagar. Local body (complete postal addresses with telephone nos. supaul to be given) 13. Name of the applicant Dhananjay kumar (Senior Architect) 14. Registered Address Kautaliya nagar patna -14 15. Address for correspondence: Bihar police Building Name cconstruction corporation Designation (Owner/Partner /CEO) Sunil kumar. Pin code ADG CUM CMD E-mail 800014 Telephone No. [email protected] Fax No. 0612-2224529 0612-2224529 16. Details of Alternative Sites examined, if any. Location of Village-District-State these sites should be shown on a topo sheet. 1 NIL 2 3 17. -

District Plan 2011 - 12

I DISTRICT PLAN 2011 - 12 SUPAUL - i I Submitted by : District Planning Committee, Supaul Submitted to: Department of Planning & Development, Government of Bihar DISTRICT PLAN 2011 - 12 SUPAUL ¥ V *k g f II A © H f: © f&T SJkH*»»* Submitted by : District Planning Committee, Supaul Submitted to: Department of Planning & Development, Government of Bihar ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For sustainable and planned economic development it is essential to formulate the Annual District Plan on the basis of available resources. As per the direction of the Department of Planning and Development, Government of Bihar, with an objective to prepare the effective Plan, we have collected relevant information and data ensuring the assimilation of district level important components from various departments as well as the priority sectors like Health, Education, Livelihood and Infrastructure etc. Keeping in view the past experience of formulation and implementation of various sectoral Action Annual Plans and recent directions of the department the Annual District Plan 2011 -12 for Rs. 103142.3 89 lakh has been prepared for the maximum utilization of available resources, so that the socio-economic development of the district can be further accelerated. I would like to thank Mr. Kunwar Jung Bahadur, Deputy Development Commissioner, Mr. D.N. Mishra, Regional Planning officer, Kosi Division, Mr. Prakash Yadav, District Planning Officer, Mr. Vivek Sharan (Ex. District Facihtator) and Mr. D P Karn, District Facihtator, GoI-UN Joint Convergence Program for their important contribution in formulation of Annual District Plan 2011 -12 for the district of Supaul. Mr. Brajesh Kumar Vikal, DPRO also deserves special thanks for his support in the Plan formulation. -

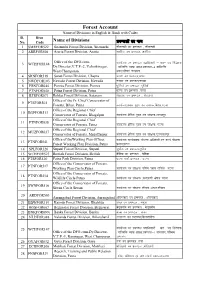

List of Forest Divisions with Code

Forest Account Name of Divisions in English & Hindi with Codes Sl. Divn No. Code Name of Divisions ize.Myksa dk uke 1 SMRFOR522 Sitamarhi Forest Division, Sitamarhi lhrke<h ou izze.My ] lhrke<h 2 ARRFOR504 Araria Forest Division, Araria vjfj;k ou ize.My] vjfj;k Office of the DFO-cum- 3 WCHFOR148 dk;kZy; ou ize.My inkf/kdkjh & lg& mi funs'kd Dy.Director,V.T.P.-2, Valmikinagar, okfYefd O;k?kz vkj{k]ize.My&2 okfYefd West Champaran uxj]if'pe pEikj.k 4 SRNFOR518 Saran Forest Division, Chapra lkj.k ou ize.My]Nijk 5 NWDFOR103 Nawada Forest Division, Nawada uoknk ou ize.My]uoknk 6 PRNFOR044 Purnea Forest Division, Purnea iwf.kZ;kWa ou izze.My ]iwf.kZ;kWa 7 PTNFOR040 Patna Forest Division, Patna iVuk ou izze.My ]iVuk 8 RTSFOR071 Rohtas Forest Division, Sasaram jksgrkl ou izze.My ] jksgrkl Office of the Pr. Chief Conservator of 9 PTSFOR501 Forests, Bihar, Patna dk;kZy;]iz/kku eq[; ou laj{kd]fcgkj]iVuk Office of the Regional Chief 10 BGPFOR513 Conservator of Forests, Bhagalpur dk;kZy; {kssf=; eq[; ou laj{kd]Hkkxyiqj Office of the Regional Chief 11 PTNFOR038 Conservator of Forests, Patna dk;kZy; {kssf=; eq[; ou laj{kd] iVuk Office of the Regional Chief 12 MUZFOR037 Conservator of Forests, Muzaffarpur dk;kZy; {ksf=; eq[; ou laj{kd]etq Q~Qjiqj Office of theWorking Plan Officer, dk;kZy; dk;Zokgd ;kstuk vf/kdkjh]ou dk; Z ;kstuk 13 PTNFOR041 Forest Working Plan Division, Patna izHkkx]iVuk 14 SPLFOR526 Supaul Forest Division, Supaul lqikSy ou ize.My]lqikSy 15 WCHFOR523 Bettiah Forest Division, Bettiah csfr;k ou izze.My ] csfr;k 16 PTSFOR530 Patna Park -

Trends, Possibilities, and Lessons

Natural Resources and their Management in Deogad Block: Trends, Possibilities, and Lessons Resources and Livelihoods Group Prayas, Pune June 2001 Table of Contents SECTION I: INTRODUCTION 1. Background 2. Objectives and Methodology of the Study 3. The Data Base and its Limitations 4. The Research Area SECTION II: THE STATUS OF NATURAL RESOURCES IN DEOGAD BLOCK 1. Land Use Pattern 2. Cropping Pattern 3. Food Production 4. Water Resources 5. Irrigation 6. Livestock 7. Human Resources SECTION III: WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT IN DEOGAD BLOCK 1. Approaches to Water Management 2. Traditional Methods 3. Modern Methods 4. Ground Water Management 5. Present Status 6. Issues and Problems in the Different Approaches 7. Institutions and Agencies for Water Resources Management 8. Generic Issues 9. Conclusion SECTION IV: REFLECTIONS AND ANALYSIS 1. Major Trends in NRM in the Block A. Transformation from Food to Cash Economy B. Mango Production – The “Unsustainable” Mainstay of Deogad Economy C. Decline of Traditional Water Management Systems: Need for a few Perspective 2. Towards a Sustainable Economy and Ecology Preface and Acknowledgements The Resources and Livelihoods (ReLi) Group of Prayas has been working on providing 'theoretical' support to various organizations working at the grassroots level in Konkan region. But its work has mainly been concentrated in the northern part of the region. 'Gramodaya Prathisthan' which is active in the southern part of the Konkan region approached ReLi with a specific request for support. The Zilla Parishad (ZP) of the Sindhudurg during the past few years initiated some innovative projects for water harvesting and management. This initiative included modernizing traditional structures, and also reviving and rebuilding some old tanks and other structures. -

Deo List Bihar

Details of DEO-cum-DM Sl. No. District Name Name Designation E-mail Address Mobile No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 PASCHIM CHAMPARAN Kundan Kumar District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191294 2 PURVI CHAMPARAN Shirsat Kapil Ashok District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191301 3 SHEOHAR Avaneesh Kumar Singh District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191468 4 SITAMARHI Abhilasha Kumari Sharma District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191288 5 MADHUBANI Nilesh Ramchandra Deore District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191324 6 SUPAUL Sri Mahendra KUMAR District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191345 7 ARARIA Prashant Kumar District Election Officer [email protected] 9431228200 8 KISHANGANJ Aditya Prakash District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191371 9 PURNIA Rahul Kumar District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191358 10 KATIHAR Kanwal Tanuj District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191375 11 MADHEPURA Navdeep Shukla District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191353 12 SAHARSA Kaushal kumar District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191340 13 DARBHANGA Shri Thiyagrajan S. M. District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191317 14 MUZAFFARPUR Chandra Shekhar Singh District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191283 15 GOPALGANJ Arshad Aziz District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191278 16 SIWAN Amit Kumar Pandey District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191273 17 SARAN Subrat Kumar Sen District -

Panchayat Samiti Elections in Maharashtra: a Data Analysis (1994-2013)

PANCHAYAT SAMITI ELECTIONS IN MAHARASHTRA: A DATA ANALYSIS (1994-2013) Rajas K. Parchure ManasiV. Phadke Dnyandev C. Talule GOKHALE INSTITUTE OF POLITICS AND ECONOMICS (Deemed to be a University)` Pune (India), 411 001 STUDY TEAM Rajas K. Parchure : Team Leader Manasi V. Phadke : Project Co-ordinator Dnyandev C. Talule Project Co-ordinator Rajesh R. Bhatikar : Editorial Desk Anjali Phadke : Statistical Assistant Ashwini Velankar : Research Assistant Vaishnavi Dande Research Assistant Vilas M. Mankar : Technical Assistance PANCHAYAT SAMITI ELECTIONS IN MAHARASHTRA : A DATA ANALYSIS (1994-2013) 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER CONTENT PAGE NO. NO. Foreword v Acknowledgements vi 1 A Historical Perspective on Local Governance 1 2 Defining Variables and Research Questions 18 3 Data Analysis: Behaviour of Main Variables 25 Across Different Rounds of Elections 4 Data Analysis: Correlations Between Key 85 Variables 5 Conclusion 86 References Appendix – A Data on VT, POL, SCST and REVERSE COMP 89 Across Rounds of Elections Appendix – B Average Values of VT, POL, RESERVE COMP 105 and IND Appendix – C Cluster Analysis of VT, POL, REVERSE COMP, 124 IND and RES Appendix – D Councils Relevant for Immediate Launch of Voter 144 Awareness Programs Appendix – E Councils Relevant for MCC Implementation 146 Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics, Pune i PANCHAYAT SAMITI ELECTIONS IN MAHARASHTRA : A DATA ANALYSIS (1994-2013) 2016 LIST OF TABLES Tables Content Page No. No. 3.1 Trends in VT across Successive Rounds of Elections 25 3.2 Panchayat Samitis belonging -

Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes Over Bihar State

CLIMATE RESEARCH AND SERVICES INDIA METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT MINISTRY OF EARTH SCIENCES PUNE Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes over Bihar State Met Monograph No. : ESSO/IMD/HS/Rainfall Variability/04(2020)/28 Pulak Guhathakurta, Sudeepkumar B L, Preetha Menon, Ashwini Kumar Prasad, Neha Sangwan and S C Advani GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF EARTH SCIENCES INDIA METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT Met Monograph No.: ESSO/IMD/HS/Rainfall Variability/04(2020)/28 Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes Over Bihar State Pulak Guhathakurta, Sudeepkumar B L, Preetha Menon, Ashwini Kumar Prasad, Neha Sangwan and S C Advani INDIA METEOROLOGICAL DEPARTMENT PUNE - 411005 1 DOCUMENT AND DATA CONTROL SHEET 1 Document Title Observed Rainfall Variability and Changes Over Bihar State 2 Issue No. ESSO/IMD/HS/Rainfall Variability/04(2020)/28 3 Issue Date January 2020 4 Security Unclassified Classification 5 Control Status Uncontrolled 6 Document Type Scientific Publication 7 No. of Pages 27 8 No. of Figures 42 9 No. of References 4 10 Distribution Unrestricted 11 Language English 12 Authors Pulak Guhathakurta, Sudeepkumar B L, Preetha Menon, Ashwini Kumar Prasad, Neha Sangwan and S C Advani 13 Originating Division/ Climate Research Division/ Climate Application & Group User Interface Group/ Hydrometeorology 14 Reviewing and Director General of Meteorology, India Approving Authority Meteorological Department, New Delhi 15 End users Central and State Ministries of Water resources, agriculture and civic bodies, Science and Technology, Disaster Management Agencies, Planning Commission of India 16 Abstract India is in the tropical monsoon zone and receives plenty of rainfall as most of the annual rainfall during the monsoon season every year. However, the rainfall is having high temporal and spatial variability and due to the impact of climate changes there are significant changes in the mean rainfall pattern and their variability as well as in the intensity and frequencies of extreme rainfall events. -

Nepali Times

#421 17 - 23 October 2008 16 pages Rs 30 Weekly Internet Poll # 421 Q. Do you expect next year’s Dasain- Tihar to be better than this year’s? Total votes: 5,319 Weekly Internet Poll # 422. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com Q. Do you think it is a good idea for the NC to join the Maoist-led coalition? EDWIN KOO RIVER TO DESERT: Just 1.5 km upstream from the Kosi Barrage in Saptari, a bull wades through stagnant water. This is where the Kosi used to flow before it suddenly breached its embankment and changed course. See also: ‘Water world’, p 8-9. combatants. But the real unknown is whether Dahal can sell that plan to his guerrilla commanders in UN-supervised cantonments. Back to work Meanwhile, there are indications of further mellowing The government has a lot of catching up to do of the Maoist line. Finance Minister Baburam Bhattarai, he friendly mood of the Although sharp differences a consensus government. attending the World Bank/IMF festive season seems to have remain, both within parties in the “We need everyone on board annual meeting in Washington Taffected the top leaders of coalition and among each other, to fulfill our immediate goals of this week, surprised people there the NC and the Maoists, who have there seems to be a realisation that keeping the peace process on and in Nepal by saying his party been using tea party diplomacy progress on governance and track, to draft a new constitution was discussing dropping ‘Maoist’ this week to patch up differences. -

Geomorphological Studies and Flood Risk Assessment of Kosi River Basin Using Remote 2011-13 Sensing and Gis Techniques

Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... 4 Lists of Figures ............................................................................................................................ 5 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 General .......................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Flood Risk Concept ....................................................................................................... 7 1.3 Background and Motivation ....................................................................................... 12 1.4 Research Questions and Objectives ............................................................................ 13 1.5 Study Area .................................................................................................................. 14 1.6 Organization of Thesis Chapters ................................................................................. 14 2. Literature Review ............................................................................................................. 16 2.1 General ........................................................................................................................ 16 2.2 Geomorphic Controls of Floods ................................................................................. -

Flood Disaster and Its Impact on the People in Kosi Region, Bihar

© 2019 IJRAR May 2019, Volume 6, Issue 2 www.ijrar.org (E-ISSN 2348-1269, P- ISSN 2349-5138) FLOOD DISASTER AND ITS IMPACT ON THE PEOPLE IN KOSI REGION, BIHAR Dr. Sanjiv Kumar Research Fellow Univ. Deptt. of Geography, T.M.B.U., Bhagalpur Introduction The Kosi, a trans-boundary river between Nepal and India is often referred to as the “Sorrow of Bihar”. The flow of the river contains excessive silt and sand, resulting in changing the courses of the river. During the past, the river has kept on changing its courses between Purnea district in the east and Darbhanga and Madhubani districts in the west. The recent disaster was created by the breach in the eastern Kosi embankment upstream of the Indian border at Kursela in the neighbouring Nepal on the 18th of August 2008. A tragedy of unparalleled dimension unleashed was over three million people living in 995 villages spreading in seven districts of Kosi region, viz. Supaul, Araria, Madhepura, Saharsa, Purnia, Khagaria and Katihar. Objectives: The purpose of the paper is to investigate the damage caused by the devastating floods due to the turbulent river Kosi recurrently and its impact on the socio-economic life of the people inhabiting in the region which is densely populated but with poor economy. The objective refers to the sustainability of an agricultural region to the occurrence of a natural disaster. The objective is to achieve in order to create a sustainable system in environmental, social and economic terms. The other objective aims to preserve or improve characteristics of the environment such as biodiversity, soil, and water and air quality. -

A Geographical Analysis of Major Tourist Attraction in Sindhudurg District, Maharashtra, India

Geoscience Research ISSN: 0976-9846 & E-ISSN: 0976-9854, Volume 4, Issue 1, 2013, pp.-120-123. Available online at http://www.bioinfopublication.org/jouarchive.php?opt=&jouid=BPJ0000215 A GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS OF MAJOR TOURIST ATTRACTION IN SINDHUDURG DISTRICT, MAHARASHTRA, INDIA RATHOD B.L.1, AUTI S.K.2* AND WAGH R.V.2 1Kankawali College Kankawali- 416 602, MS, India. 2Art, Commerce and Science College, Sonai- 414 105, MS, India. *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: October 12, 2013; Accepted: December 09, 2013 Abstract- Sindhudurg District has been declared as a 'Tourism District' on 30th April 1997. The natural resources, coastal lines, waterfalls, hot springs, temples, historical forts, caves, wild-life, hill ranges, scenery and amenable climate are very important resources of tourist attrac- tion. The various facilities available to the domestic and foreign tourists in Sindhudurg district. These include natural resources, transportation, infrastructure, hospitality resources and major tourist attractions. For the research work Sindhudurg District is selected. This district has at East Kolhapur district, at south Belgaum and Goa state at North Ratnagiri district and at west Arabian Sea. It is smallest district in Maharashtra state. It's area is 5207 sq.kms. Its geographical Location of Sindhudurg is 150 36' to 160 40' North latitudes as 730 19 to 740 18' East longitude. As per 2001 census it has 743 inhabited villages and 5 towns. The object of study region is, to highlight the attractive tourist destinations and religious places in the region. This study based on primary and secondary data. Tourist attractions in the district as is, natural beauty, waterfall, umala, caves, temples, beaches, ports, forts, mini garden, rock garden, tracking, rock climbing, boating, valley crossing, wild life, festival's fairs, arts, handicrafts, creeks, lakes etc. -

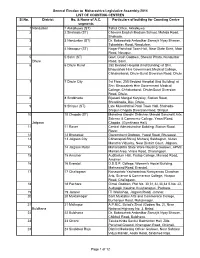

V E 2014 Counting Centres

General Election to Maharashtra Legislative Assembly-2014 LIST OF COUNTING CENTRES Sl.No. District No. & Name of A.C. Particulars of building for Counting Centre segments 1 Nandurbar 1 Akkalkuwa (ST) Tahsil Office, Akkalkuwa 2 2 Shahada (ST) Chavara English Medium School, Mohida Road, Shahada. 3 3 Nandurbar (ST) Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Samajik Nyay Bhavan, Tokartalav Road, Nandurbar. 4 4 Nawapur (ST) Nagar Parishad Town Hall, Near State Bank, Main Road, Navapur. 5 5 Sakri (ST) Govt. Grain Godown, Shewali Phata, Nandurbar Dhule Road, Sakri. 6 6 Dhule Rural 250 Bedded Hospital (Iind Building) at Shri. Bhausaheb Hire Government Medical College, Chhakarbardi, Dhule-Surat Diversion Road, Dhule. 7 7 Dhule City 1st Floor, 250 Bedded Hospital (Iind Building) at Shri. Bhausaheb Hire Government Medical College, Chhakarbardi, Dhule-Surat Diversion Road, Dhule. 8 8 Sindkheda Bijasani Mangal Karyalay, Station Road, Shindkheda, Dist. Dhule. 9 9 Shirpur (ST) Late Mukeshbhai Patel Town Hall, Shahada- Shirpur-Chopda Diversion Road, Shirpur. 10 10 Chopda (ST) Mahatma Gandhi Shikshan Mandal Sanchalit Arts, Science & Commerce College, Yawal Road, Jalgaon Chopda. (Gymkhana Hall) 11 11 Raver Central Administrative Building, Station Road, Raver. 12 12 Bhusawal Government Godown, Yawal Road, Bhusawal. 13 13 Jalgaon City Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Sabhagruh, Nutan Maratha Vidyalay, Near District Court, Jalgaon. 14 14 Jalgaon Rural Maharashtra State Ware Housing Godown, APMC Market Area, Virare Road, Dharangaon. 15 15 Amalner Auditorium Hall, Pratap College, Marwad Road, Amalner. 16 16 Erandol D.D.S.P. College, Women's Hostel Building, Mahsawad Road, Erandol. 17 17 Chalisgaon Nanasaheb Yashwantrao Narayanrao Chawhan Arts, Science & Commerece College, Hirapur Road, Chalisgaon.