Privately Operated Federal Prisons for Immigrants: Expensive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verse Translation of Three Lays of Marie De

Verse translations of three lays of Marie de France Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Rhodes, Lulu Hess, 1907- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 04:44:15 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553240 Verse Translation of Three Lays of Marie de France by Lulu Hess Rhodes Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 19 3 5 Approved: JF9?9/ / 9 3 S' 33 Z CONTENTS Introduction ....... 1 Guif-emar ............ 9 L ’Aiistic..................... 79 Mllun ........................... 93 9 9 * 9 9 ISflGDUCTIOI The earliest and most mysterious French poetess lived in the twelfth century, a cent wry dominated fcy the feudal system with its powerful lords and their nofele chevaliers. Much of the pomp, heraldry, movement, and color of the trad ition® of chivalry appeared in the chanson® de geste, stories of Idealized national heroes. The knight® of the chansons, noble, valorous men, flawless in their devotion to king, God, and the cause of right,— those chevaliers whose deed® were sung and celebrated wherever a jongleur presided in the great hall of a chateau, were admirable types of a tradition of French glory and power. The age of chivalry was presented in yet another manner in the twelfth century. -

Against All Odds: a Peer-Supported Recovery Partnership 2

Against All Odds: A Peer-Supported Recovery Partnership 2 PSA Behavioral Health Agency • History • Programs 3 Odds Against: Mental Illness • In 2012 it is estimated that 9.6 million adults aged 18 or older in the United States had been diagnosed with a Serious Mental Illness (SAMHSA: Prevention of Substance Abuse and Mental Illness, 2014) • Additionally, 23.1 million persons in the United States age 12 and older have required treatment services for Substance Use disorders (SAMHSA: Prevention of Substance Abuse and Mental Illness, 2014 ) 4 Odds Against: Bureau of Justice Statistics • Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates: Special Report (September 2006 NCJ 213600) 1. Mental Health problems defined by recent history or symptoms of a mental health problem 2. Must have occurred in the last 12 months 3. Clinical diagnosis or treatment by a behavioral health professional 4. Symptoms were diagnosed based upon criteria specified in DSM IV 5 Odds Against: Bureau of Justice Statistics • Approximately 25% of inmates in either local jails or prisons with mental illness had been incarcerated 3 or more times • Between 74% and 76% of State prisoners and those in local jails met criteria for substance dependence or abuse • Approximately 63% of State prisoners with a mental health disorder had used drugs in the month prior to their arrests 6 Odds Against: Bureau of Justice Statistics • 13% of state prisoners who had a mental health diagnoses prior to incarceration were homeless within the year prior to their arrest • 24% of jail inmates with a mental health diagnosis reported physical or sexual abuse in their past • 20% of state prisoners who had a mental health diagnosis were likely to have been in a fight since their incarceration 7 Odds Against: Homelessness • 20 to 25% of the homeless population in the United States suffers from mental illness according to SAMHSA (National Institute of Mental Health, 2009) • In a 2008 survey by the US Conference of Mayors the 3rd largest cause of homelessness was mental illness. -

Against All Odds? the Political Potential of Beirut’S Art Scene

Against all odds? The political potential of Beirut’s art scene Heinrich Böll Stiftung Middle East 15 October 2012 – 15 January 2013 by Linda Simon & Katrin Pakizer This work is licensed under the “Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Germany License”. To view a copy of this license, visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/de/ Against all odds? The political potential of Beirut’s art scene Index 1. Introduction 3 2. “Putting a mirror in front of yourself”: Art & Change 5 3. “Art smoothens the edges of differences”: Art & Lebanese Culture 6 4. “You can talk about it but you cannot confront it”: Art & Censorship 10 5.”We can’t speak about art without speaking about economy”: Art & Finance 13 6. Conclusion 17 7. Sources 20 Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung - Middle East Office, 2013 2 Against all odds? The political potential of Beirut’s art scene 1. Introduction "I wish for you to stand up for what you care about by participating in a global art project, and together we'll turn the world... INSIDE OUT." These are the words of the French street art artist JR introducing his project INSIDE OUT at the TED prize wish speech in 2011. His project is a large-scale participatory art project that transforms messages of personal stories into pieces of artistic work. Individuals as well as groups are challenged to use black and white photographic portraits to discover, reveal and share the untold stories of people around the world about topics like love, peace, future, community, hope, justice or environment1. -

Against All Odds: from Prison to Graduate School

Journal of African American Males in Education Spring 2015 - Vol. 6 Issue 1 Against All Odds: From Prison to Graduate School Rebecca L. Brower Florida State University This case study explores an often overlooked phenomenon in the higher education literature: Students transitioning from prison to college. The case presents the unique story of an African American male who made a series of life transitions from federal prison to homelessness to community college to a historically Black university, and finally to a predominantly White institution for graduate school. These transitions came as the result of successful coping strategies, which included social learning, hope, optimism, information seeking, and meaning-making. Some of the policy and research implications of ex-convicts returning to higher education after imprisonment are also considered. Keywords: African-American, Black, college access, prison, transition A middle-aged African American male named Robert Jones sits in a community college classroom feeling overwhelmed and unsure of himself. He has been released after spending ten years in federal prison for drug trafficking. After prison, he was homeless for a period of time, but now he is sitting in a community college classroom thanks to his own efforts and the local homeless coalition’s program to help ex-convicts gain housing, employment, and education. He vividly describes his experience on his first day of community college: I tell you, I swear my head was hurting. I’m serious. I was, like, in class, you know, like Charlie Brown, I had sparks going everywhere. I was like, it’s like that came to my mind and I was like now I see how Charlie Brown feels. -

Vol. 2 No. 3, 2012

KOMANEKA Update Home Photo Album Spa Promotion Vol. 2 No. 3, Sep. 2012 A SLICE OF THE GODS PACKAGE Ngejot Tumpeng Anten, – The TRIPLE SPECIAL Prayer of Newlyweds in Ubud ...FREE extra bed and ...there is another side of Galungan, Breakfast for the third Ngejot Tumpeng Anten procession, that is person... unique and indigenous to Ubud and some villages in Gianyar... Galungan is the most awaited day for Balinese, where various festivities become part of this special day. The streets will be full of janur (young coconut Show your near and dear ones that you care. Valid leaves) decorations, the scent of incense, and the for all room category at Komaneka at Tanggayuda, happy sounds of children in the air welcoming Komaneka at Bisma, and Komaneka at Rasa Sayang. Barong Ngelawang (lawang = door) dancing from door to door. Stay period starting 1 October 2012 - 30 April 2013. Galungan is an ancient Javanese word meaning to win or to fight. Galungan also has the same meaning with Dungulan, to win. The Galungan Festivity for Balinese means the expression of joy in celebration of dharma (goodness) winning over adharma (evil). click to continue click to continue KOMANEKA WHAT TO READ FINE ART GALLERY AGAINST ALL ODDS I Wayan Sujana Suklu ...Intricacies in the Life of a Balinese Prince... I Wayan Sujana affectionately goes by the name The arrival of the Dutch marks the end of the glory Suklu. Suklu is short for Sujana Klungkung, meaning of the kingdom era in Bali. One by one the Balinese Sujana who comes from Klungkung. Klungkung used kings surrender and must give up their power to be the location of the central government, where to the colonial government. -

Against All Odds? Birth Fathers and Enduring Thoughts of the Child Lost to Adoption

genealogy Article Against All Odds? Birth Fathers and Enduring Thoughts of the Child Lost to Adoption Gary Clapton School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH8 9YL, UK; [email protected] Received: 4 March 2019; Accepted: 25 March 2019; Published: 29 March 2019 Abstract: This paper revisits a topic only briefly raised in earlier research, the idea that the grounds for fatherhood can be laid with little or no ‘hands-on’ experience of fathering and upon these grounds, an enduring sense of being a father of, and bond with, a child seen once or never, can develop. The paper explores the specific experiences of men whose children were adopted as babies drawing on the little research that exists on this population, work relating to expectant fathers, personal accounts, and other sources such as surveys of birth parents in the USA and Australia. The paper’s exploration and discussion of a manifestation of fatherhood that can hold in mind a ‘lost’ child, disrupts narratives of fathering that regard fathering as ‘doing’ and notions that once out of sight, a child is out of mind for a father. The paper suggests that, for the men in question, a diversity of feelings, but also behaviours, point to a form of continuing, lived fathering practices—that however, take place without the child in question. The conclusion debates the utility of the phrase “birth father” as applied historically and in contemporary adoption processes. Keywords: birth fathers; adoption; fatherhood 1. Introduction There can be an enduring psychological/attachment bond between the child and their biological father that is of significance both to the child and the father, whether the father is present, absent or indeed has never been known to the child (Clapton 2007, pp. -

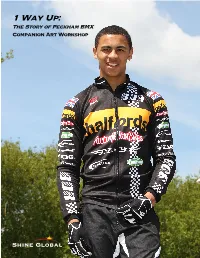

1 Way Up: the Story of Peckham BMX Companion Art Workshop 1 WAY up COMPANION ART WORKSHOP

1 Way Up: The Story of Peckham BMX Companion Art Workshop 1 WAY UP COMPANION ART WORKSHOP Overview of the Film Peckham, London is one of the most notorious areas in the UK. It is known in the media and to most Londoners as one of the neighborhoods most affected by the London riots and the scene of the brutal murder of 10-year-old Damilola Taylor by 12 and 13-year old brothers. It is an area rife with unemployment and youth gang activity. But the Peckham BMX club is starting to change that image, bringing BMX riders to podiums around the country. One of these is 17-year-old Tre Whyte. Ranked third in the nation, CK is pushing him to win the National Championship and compete in the Olympics. Director: Amy Mathieson Family volatility and poverty have caused Tre to move out of his home, forcing him to make adult decisions at a young age. Without support, it will be a tough Producers: Albie Hecht and climb to the top. Amy Mathieson Quillan Isidore is only 16 but already a 3-time British BMX champion. But www.1wayup.com even as a champion he’s still subjected to continuing gang pressure in Twitter: @1WayUpMovie the neighborhood while the competition to become World Champion from Facebook.com/1WayUp3D sponsored riders is steep. To get a copy of the film and the public screening license: The film follows Tre, Quillan, and CK’s preparation, victories and defeats, and [email protected] interactions with family and friends, all leading up to the World Championships. -

Fighting Against All Odds: Entrepreneurship Education As Employability Training

the author(s) 2013 ISSN 1473-2866 (Online) ISSN 2052-1499 (Print) www.ephemerajournal.org volume 13(4): 717-735 Fighting against all odds: Entrepreneurship education as employability training Karin Berglund abstract In this paper the efforts of transforming ‘regular’ entrepreneurship to a specific kind of ‘entrepreneurial self’ in education are linked to the materialization of employability. It will be illustrated that schoolchildren, under the guise of entrepreneurship education, are taught how to work on improving their selves, emphasizing positive thinking, the joy of creating and awareness of the value of their own interests and passions. This ethic reminds us that we can always improve ourselves, since the enterprising self can never fully be acquired. The flipside of this ethic is that, by continuously being encouraged to become our best, it may be difficult to be satisfied with who we are. Highlighted in this paper is that, with all the amusement and excitement present in entrepreneurship education, also comes an expectation of the individual to fight against all odds. Recruiting students to this kind of shadow-boxing with their selves should involve critical reflection on its political dimensions, human limits, alternative ideals and the collective efforts that are part of entrepreneurial endeavours. Prologue ‘I have never needed to look for a job. I found my own way.’ It is an evening when dinnertime has been delayed due to one of those deadlines that most academics continually seem to struggle with. The TV is on in the background and I am just about to get the dinner ready when I hear a woman talk about how she made it as an entrepreneur in life, never having to search for a job, but carving out a life path of her own. -

AGAINST ALL ODDS How Independent Retail, Hospitality and Services Businesses Have Adapted to Survive the Pandemic a Grimsey Review Research Paper AGAINST ALL ODDS

A Grimsey Review Research Paper AGAINST ALL ODDS How independent Retail, Hospitality and Services Businesses have adapted to survive the pandemic A Grimsey Review Research Paper AGAINST ALL ODDS Key Findings ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Foreword .....................................................................................................................................................................................................6 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Recommendations ..........................................................................................................................................................................18 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 24 State of the Nation ..........................................................................................................................................................................28 The impact of the pandemic on our high streets and town centres has rarely been out of the headlines, fuelled by high profile collapses involving iconic retail brands. However, little -

Approved Movie List 10-9-12

APPROVED NSH MOVIE SCREENING COMMITTEE R-RATED and NON-RATED MOVIE LIST Updated October 9, 2012 (Newly added films are in the shaded rows at the top of the list beginning on page 1.) Film Title ALEXANDER THE GREAT (1968) ANCHORMAN (2004) APACHES (also named APACHEN)(1973) BULLITT (1968) CABARET (1972) CARNAGE (2011) CINCINNATI KID, THE (1965) COPS CRUDE IMPACT (2006) DAVE CHAPPEL SHOW (2003–2006) DICK CAVETT SHOW (1968–1972) DUMB AND DUMBER (1994) EAST OF EDEN (1965) ELIZABETH (1998) ERIN BROCOVICH (2000) FISH CALLED WANDA (1988) GALACTICA 1980 GYPSY (1962) HIGH SCHOOL SPORTS FOCUS (1999-2007) HIP HOP AWARDS 2007 IN THE LOOP (2009) INSIDE DAISY CLOVER (1965) IRAQ FOR SALE: THE WAR PROFITEERS (2006) JEEVES & WOOSTER (British TV Series) JERRY SPRINGER SHOW (not Too Hot for TV) MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE, THE (1962) MATA HARI (1931) MILK (2008) NBA PLAYOFFS (ESPN)(2009) NIAGARA MOTEL (2006) ON THE ROAD WITH CHARLES KURALT PECKER (1998) PRODUCERS, THE (1968) QUIET MAN, THE (1952) REAL GHOST STORIES (Documentary) RICK STEVES TRAVEL SHOW (PBS) SEX AND THE SINGLE GIRL (1964) SITTING BULL (1954) SMALLEST SHOW ON EARTH, THE (1957) SPLENDER IN THE GRASS APPROVED NSH MOVIE SCREENING COMMITTEE R-RATED and NON-RATED MOVIE LIST Updated October 9, 2012 (Newly added films are in the shaded rows at the top of the list beginning on page 1.) Film Title TAMING OF THE SHREW (1967) TIME OF FAVOR (2000) TOLL BOOTH, THE (2004) TOMORROW SHOW w/ Tom Snyder TOP GEAR (BBC TV show) TOP GEAR (TV Series) UNCOVERED: THE WAR ON IRAQ (2004) VAMPIRE SECRETS (History -

From the Middle of Nowhere to the Arlington Million, Little Bro Lantis Captured the Imagination of Small-Time Horsemen Everywhere by Denis Blake Four Footed Fotos

Against All Odds From the middle of nowhere to the Arlington Million, Little Bro Lantis captured the imagination of small-time horsemen everywhere By Denis Blake Four Footed Fotos Footed Four South Dakota-bred Little Bro Lantis and Louisiana trainer Merrill Scherer won the 1993 Stars and Stripes Handicap (G3) at Arlington Park at odds of 43-1. 34 SOUTHERN RACEHORSE • NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2013 Despite having a population of about 800,000 in the entire state, have to worry about thumbing through a thick stallion directory. South Dakota can lay claim to more than its share of racing icons. “Lost Atlantis was really one of the only nicely bred horses in South To name just a few, Bill Mott, D. Wayne Lukas and brothers Cash Dakota and as far as I know the only Northern Dancer son that stood and Steve Asmussen all have strong ties to the state. Although Lukas around here,” Ryno said about the stallion who earned $12,754 on the was born in Wisconsin, he cut his teeth as a trainer at the now extinct track and stood at Everett Smalley’s Smalley Farm in Fort Pierre. Park Jefferson in the state’s Since the pairing of southeast corner near the Southern Tami and Lost Iowa and Nebraska border. Atlantis seemed to work, Before South Dakota native Ryno decided to breed Mott trained the incom- them just about every parable Cigar, he saddled season, and in 1988 the his first winner on the mare produced her fourth state’s bush track circuit foal by the stallion. -

Success Against All Odds Lessons Learned from Successful, Impoverished Students

Running head: SUCCESS 1 Success Against All Odds Lessons Learned from Successful, Impoverished Students Amanda King A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Fall 2014 SUCCESS 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. _________________________ Samuel J. Smith, Ed.D. Thesis Chairman _________________________ Esther Alcindor, M.Ed. Committee Member _________________________ James A. Borland, Th.D. Committee Member _________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director _________________________ Date SUCCESS 3 Abstract The effects of poverty on students’ education have been well documented and a positive correlation can be seen between these effects and their academic success. What is unclear, however, are the exceptions to this correlation. How do students from low-socio- economic status (SES) families succeed despite the seemingly insurmountable odds they face? The literature from a wide variety of longitudinal—and interview-based studies from the past three decades suggests that character traits such as persistence, determination, and curiosity are key to their success. Schools with a majority student body from low-SES homes have found success in meeting and exceeding state standards through fostering an encouraging atmosphere and incorporating these necessary character traits throughout their curriculum. Mentorship in developing these traits is what makes all the difference in both the individual students’ lives and in the school setting. Thus, in order to sustain the development of academically successful students, it is imperative that students not only believe that they can succeed, but that they are given avenues and resources through which they can succeed.