A Case of Serious Misguidance ‘Big Charlie’ Thomas – Or Charlie Gaines?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tri-State Skylark Strutter

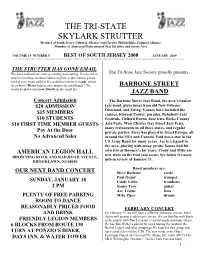

THE TRI-STATE SKYLARK STRUTTER Member of South Jersey Cultural Alliance and Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance Member of American Federation of Jazz Societies and Jersey Arts VOLUME 19 NUMBER 5 BEST OF SOUTH JERSEY 2008 JANUARY 2009 ********************************************************************************************************************************* .THE STRUTTER HAS GONE EMAIL We have reduced our costs of printing and mailing. If you wish to The Tri-State Jazz Society proudly presents: help by receiving an email edition in place of this edition, please send in your email address If you did not receive it in pdf, please let us know! Please help us save money for good bands!! We BARBONE STREET would be glad to put your friends on the email list. JAZZ BAND Dd Concert Admission The Barbone Street Jazz Band, the area’s busiest $20 ADMISSION jazz band, plays tunes from old New Orleans, Dixieland, and Swing. Venues have included the $15 MEMBERS casinos, Kimmel Center, parades, Rehoboth Jazz $10 STUDENTS Festivals, Clifford Brown Jazz fests, Berks County $10 FIRST TIME MEMBER GUESTS Jazz Fests, West Chester Gay Street Jazz Fests, many restaurants in all three states, and regular Pay At the Door private parties. Steve has played in Israel Europe, all No Advanced Sales around the USA and Canada. Paul was a star in the S US Army Band for many years. Ace is a legend in the area, playing with many greats. Sonny had his AMERICAN LEGION HALL own trio at Downey’s for years. Cindy and Mike are new stars on the trad jazz scene. See below for more BROWNING ROAD AND RAILROAD AVENUE, info in review of January 11. -

Selected Observations from the Harlem Jazz Scene By

SELECTED OBSERVATIONS FROM THE HARLEM JAZZ SCENE BY JONAH JONATHAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-Newark Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jazz History and Research Written under the direction of Dr. Lewis Porter and approved by ______________________ ______________________ Newark, NJ May 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Page 3 Abstract Page 4 Preface Page 5 Chapter 1. A Brief History and Overview of Jazz in Harlem Page 6 Chapter 2. The Harlem Race Riots of 1935 and 1943 and their relationship to Jazz Page 11 Chapter 3. The Harlem Scene with Radam Schwartz Page 30 Chapter 4. Alex Layne's Life as a Harlem Jazz Musician Page 34 Chapter 5. Some Music from Harlem, 1941 Page 50 Chapter 6. The Decline of Jazz in Harlem Page 54 Appendix A historic list of Harlem night clubs Page 56 Works Cited Page 89 Bibliography Page 91 Discography Page 98 3 Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to all of my teachers and mentors throughout my life who helped me learn and grow in the world of jazz and jazz history. I'd like to thank these special people from before my enrollment at Rutgers: Andy Jaffe, Dave Demsey, Mulgrew Miller, Ron Carter, and Phil Schaap. I am grateful to Alex Layne and Radam Schwartz for their friendship and their willingness to share their interviews in this thesis. I would like to thank my family and loved ones including Victoria Holmberg, my son Lucas Jonathan, my parents Darius Jonathan and Carrie Bail, and my sisters Geneva Jonathan and Orelia Jonathan. -

The Journal of the Duke Ellington Society Uk Volume 23 Number 3 Autumn 2016

THE JOURNAL OF THE DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK VOLUME 23 NUMBER 3 AUTUMN 2016 nil significat nisi pulsatur DUKE ELLINGTON SOCIETY UK http://dukeellington.org.uk DESUK COMMITTEE HONORARY MEMBERS OF DESUK Art Baron CHAIRMAN: Geoff Smith John Lamb Vincent Prudente VICE CHAIRMAN: Mike Coates Monsignor John Sanders SECRETARY: Quentin Bryar Tel: 0208 998 2761 Email: [email protected] HONORARY MEMBERS SADLY NO LONGER WITH US TREASURER: Grant Elliot Tel: 01284 753825 Bill Berry (13 October 2002) Email: [email protected] Harold Ashby (13 June 2003) Jimmy Woode (23 April 2005) MEMBERSHIP SECRETARY: Mike Coates Tel: 0114 234 8927 Humphrey Lyttelton (25 April 2008) Email: [email protected] Louie Bellson (14 February 2009) Joya Sherrill (28 June 2010) PUBLICITY: Chris Addison Tel:01642-274740 Alice Babs (11 February, 2014) Email: [email protected] Herb Jeffries (25 May 2014) MEETINGS: Antony Pepper Tel: 01342-314053 Derek Else (16 July 2014) Email: [email protected] Clark Terry (21 February 2015) Joe Temperley (11 May, 2016) COMMITTEE MEMBERS: Roger Boyes, Ian Buster Cooper (13 May 2016) Bradley, George Duncan, Frank Griffith, Frank Harvey Membership of Duke Ellington Society UK costs £25 SOCIETY NOTICES per year. Members receive quarterly a copy of the Society’s journal Blue Light. DESUK London Social Meetings: Civil Service Club, 13-15 Great Scotland Yard, London nd Payment may be made by: SW1A 2HJ; off Whitehall, Trafalgar Square end. 2 Saturday of the month, 2pm. Cheque, payable to DESUK drawn on a Sterling bank Antony Pepper, contact details as above. account and sent to The Treasurer, 55 Home Farm Lane, Bury St. -

Ernest Elliott

THE RECORDINGS OF ERNEST ELLIOTT An Annotated Tentative Name - Discography ELLIOTT, ‘Sticky’ Ernest: Born Booneville, Missouri, February 1893. Worked with Hank Duncan´s Band in Detroit (1919), moved to New York, worked with Johnny Dunn (1921), etc. Various recordings in the 1920s, including two sessions with Bessie Smith. With Cliff Jackson´s Trio at the Cabin Club, Astoria, New York (1940), with Sammy Stewart´s Band at Joyce´s Manor, New York (1944), in Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith´s Band (1947). Has retired from music, but continues to live in New York.” (J. Chilton, Who´s Who of Jazz) STYLISTICS Ernest Elliott seems to be a relict out of archaic jazz times. But he did not spend these early years in New Orleans or touring the South, but he became known playing in Detroit, changing over to New York in the very early 1920s. Thus, his stylistic background is completely different from all those New Orleans players, and has to be estimated in a different way. Bushell in his book “Jazz from the Beginning” says about him: “Those guys had a style of clarinet playing that´s been forgotten. Ernest Elliott had it, Jimmy O´Bryant had it, and Johnny Dodds had it.” TONE Elliott owns a strong, rather sharp, tone on the clarinet. There are instances where I feel tempted to hear Bechet-like qualities in his playing, probably mainly because of the tone. This quality might have caused Clarence Williams to use Elliott when Bechet was not available? He does not hit his notes head-on, but he approaches them with a fast upward slur or smear, and even finishes them mostly with a little downward slur/smear, making his notes to sound sour. -

The Recordings

Appendix: The Recordings These are the URLs of the original locations where I found the recordings used in this book. Those without a URL came from a cassette tape, LP or CD in my personal collection, or from now-defunct YouTube or Grooveshark web pages. I had many of the other recordings in my collection already, but searched for online sources to allow the reader to hear what I heard when writing the book. Naturally, these posted “videos” will disappear over time, although most of them then re- appear six months or a year later with a new URL. If you can’t find an alternate location, send me an e-mail and let me know. In the meantime, I have provided low-level mp3 files of the tracks that are not available or that I have modified in pitch or speed in private listening vaults where they can be heard. This way, the entire book can be verified by listening to the same re- cordings and works that I heard. For locations of these private sound vaults, please e-mail me and I will send you the links. They are not to be shared or downloaded, and the selections therein are only identified by their numbers from the complete list given below. Chapter I: 0001. Maple Leaf Rag (Joplin)/Scott Joplin, piano roll (1916) listen at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9E5iehuiYdQ 0002. Charleston Rag (a.k.a. Echoes of Africa)(Blake)/Eubie Blake, piano (1969) listen at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R7oQfRGUOnU 0003. Stars and Stripes Forever (John Philip Sousa, arr. -

The Influence of Louis Armstrong on the Harlem Renaissance 1923-1930

ABSTRACT HUMANITIES DECUIR, MICHAEL B.A. SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS, 1987 M.A. THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, 1989 THE INFLUENCE OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE 1923–1930 Committee Chair: Timothy Askew, Ph.D. Dissertation dated August 2018 This research explores Louis Armstrong’s artistic choices and their impact directly and indirectly on the African-American literary, visual and performing arts between 1923 and 1930 during the period known as the Harlem Renaissance. This research uses analyses of musical transcriptions and examples of the period’s literary and visual arts to verify the significance of Armstrong’s influence(s). This research also analyzes the early nineteenth century West-African musical practices evident in Congo Square that were present in the traditional jazz and cultural behaviors that Armstrong heard and experienced growing up in New Orleans. Additionally, through a discourse analysis approach, this research examines the impact of Armstrong’s art on the philosophical debate regarding the purpose of the period’s art. Specifically, W.E.B. Du i Bois’s desire for the period’s art to be used as propaganda and Alain Locke’s admonitions that period African-American artists not produce works with the plight of blacks in America as the sole theme. ii THE INFLUENCE OF LOUIS ARMSTRONG ON THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE 1923–1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF CLARK ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY MICHAEL DECUIR DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA AUGUST 2018 © 2018 MICHAEL DECUIR All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest debt of gratitude goes to my first music teacher, my mother Laura. -

BLUES UNLIMITED Number Four (August 1963)

BLUES UN LI Ml TED THE JOURNAL OF “THE BLUES APPRECIATION SOCIETY” EDITED BY SIMON A. NAPIER - Jiiiiffiber Four August 196^ ; purposes of ^'HLues Unlimited* &re several-fold* To find out more about tlse singers is : §1? iiaportant one* T® document th e ir records . equally so,, This applies part!cularly with .postwar "blues ' slmgers and labels. Joho Godrieh m d Boh Dixon ? with the Concert ed help> o f many collectors? record companies imd researchers* .^aTe/v.niide^fHitpastri'Q. p|»©gr;e8Sv, In to l i ‘s.ting. the blues records made ■ parlor to World War IXa fn a comparatively short while 3 - ’with & great deal of effort,.they have brought the esad of hlues discog raphy prewar- in sights Their book?. soon t® be published, w ill be the E?5?st valuable aid. 't o blues lovers yet compiled,, Discography of-;p©:stw£sr ...artists....Is,.In.-■■. a fa r less advanced state* The m&gasine MBlues Research1^ is doing. amagni fieezst- ^ob with : postwar blues;l^bei:s:^j Severd dis^grg^hers are active lis tin g the artists' work* We are publishing Bear-complete discographies xb the hope that you3 the readers^ w ill f i l l In the gaps* A very small proportion o f you &re: helping us in this way0 The Junior Farmer dis&Oc.: in 1 is mow virtu ally complete« Eat sursiy . :s®eb®ciy,:h&s; Bake^;31^;^: 33p? 3^o :dr3SX* Is i t you? We h&veii#t tie&rd from y<&ia£ Simil^Xy: ^heM. -

![Frank Driggs Collection of Duke Ellington Photographic Reference Prints [Copy Prints]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8847/frank-driggs-collection-of-duke-ellington-photographic-reference-prints-copy-prints-1348847.webp)

Frank Driggs Collection of Duke Ellington Photographic Reference Prints [Copy Prints]

Frank Driggs Collection of Duke Ellington Photographic Reference Prints [copy prints] NMAH.AC.0389 NMAH Staff 2018 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 2 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Series 1: Band Members......................................................................................... 3 Series 2: Ellington at Piano...................................................................................... 5 Series 3: Candid Shots............................................................................................ 6 Series : Ellington -

William Russell Collection

MSS 506 Interviews with Musicians about Jelly Roll Morton 1938-1991 Bulk dates 1968-1970 Extent: 487 items This collection, a part of the larger William Russell Collection, consists of typed interviews about the jazz composer, pianist, and conductor Ferdinand “Jelly Roll” Morton (1885?-1941) and of other material which Russell collected for an intended book about Morton. The title of the collection derives from Russell‟s own descriptive phrase on folders and other packing material. However, the interviews were conducted not only with musicians, but also with others who could shed some light on Morton‟s story, including Frances M. Oliver (folder #118), Morton‟s sister; Joseph Fogarty (folder #54), grandson of Judge John J. Fogarty, who is mentioned in a Morton song; two retired vaudeville performers known as Mack and Mack (folder #108); Morton‟s one- time manager Harrison Smith (folder #174); and many others. Also in this collection are a few letters (folder #157, for instance), many of Jelly Roll‟s own autobiographical writings (folder #104), and several clippings, including an important obituary of Roy Carew (folder #87). The few photographs (none of Morton) are generally those mentioned in the accompanying interview article, and were probably intended as illustrations. Russell also collected the output of other people‟s research. John Steiner‟s chronology, “Jelly Roll in The Chicago Defender” (folders 183-185) and the beginning of Dave Stuart‟s book about his own friendship with Morton (folders 187-191) are examples of these. This material served as the basis for William Russell‟s book “Oh Mister Jelly!”: A Jelly Roll Morton Scrapbook. -

Otto Hardwick Duke Ellington´S Sweet Alto Saxophonist

BULLETIN NR 1, JANUARI 2017, ÅRGÅNG 25 Otto Hardwick Duke Ellington´s sweet alto saxophonist I detta nummer / In this issue: 2 Ledare m. m. 3 Recensioner 4 Otto Hardwick 9 Willie Cook with Dizzy Gillespie 10 Willie Cook with Billie Holiday 11 Olle Snismark 12 Milt Hinton and Duke Ellington 13 Other Duke´s Places 14 Nya skivor 15 When Jazz Had The Blues 16 A Swedish singer with Duke Ellington 17 Adelaide Hall 18 Duke Ellington in Europe 20 Kallelse 1-2017 Nu tar vi nya tag Alla våra medlemmar önskas en god den 13 februari engagera två erkänt bra av kassan. Jag känner mig övertygad fortsättning på det nya året. Med det musiker med synnerligen gott renommé. om att årsmötet kommer att godkänna önskar jag även en god fortsättning för Det rör sig om teamet Kjell Fernström vår begäran. Alla årsmöteshandlingar vår förening och att vårt medlemsantal och Mårten Lundgren (se kallelse på kommer att fnnas tillgängliga inför skall öka. Den CD som vi skickade ut sid. 20). Detta innebär att kostnaden för mötet. med förra Bulletinen har rönt ett gott evenemanget höjs och vi tvingas därför När jag ändå är inne på ekonomifrågor mottagande och något annat hade jag höja entréavgiften till 200:-, men vi tror så hoppas jag att alla våra medlemmar inte väntat mig. Den speglade ju en och hoppas att våra medlemmar skall få kommer att använda sig av det höjdpunkt i Duke Ellingtons karriär. Vi valuta för sina pengar. inbetalningskort som bifogades förra räknar med att senast under 2018 kunna Det kommande medlemsmötet är Bulletinen. -

Albert 'Happy' Caldwell

THE RECORDINGS OF ALBERT ‘HAPPY’ CALDWELL An Annotated Tentative Personnelo-Discography CALDWELL, Albert W. ‘Happy’ born: Chicago, Ill., 25 July, 1903; died: New York, 29 December, 1978 Attended Wendell Phillips High School in Chicago, studied pharmacy. Took up clarinet in 1919. Played clarinet in 8th Illinois Regimental Band, after Army service took lessons from his cousin, Buster Bailey. Returned to studies until 1922, then joined Bernie Young´s Band at Columbia Tavern, Chicago, mage his first records with Young in 1923 (‘Dearborn Street Blues’), began doubling tenor c. 1923. Toured in Mamie Smith´s Jazz Hounds, remained in New York (1924). Did summer season at Asbury Park, then joined Bobby Brown´s Syncopators (1924). Worked with Elmer Snowden (1925), also with Billy Fowler, Thomas Morris, etc. With Willie Gant´s Ramblers (summer 1926), worked with Cliff Jackson, also toured with Keep Shufflin´ revue (early 1927). With Arthur Gibbs´ Orchestra (summer 1927 to summer 1928), recorded with Louis Armstrong (1929), also worked with Elmer Snowden again, Charlie Johnson, Fletcher Henderson, etc. Regularly with Vernon Andrade´s Orchestra from 1929 until 1933. With Tiny Bradshaw (1934), Louis Metcalf (1935), then led own band, mainly in New York. Recorded with Jelly Roll Morton (1939), with Willie Gant (1940). After leading his Happy Pals at Minton´s in early 1941, he moved to Philadelphia for three years, occasionally led own band, also worked with Eugene ‘Lonnie’ Slappy and his Swingsters and Charlie Gaines. Returned to New York in January 1945. Active with own band throughout the 1950s and 1960s, many private engagements and residencies at Small´s (1950-3), Rockland Palace (1957), etc., also gigged with Louis Metcalf and Jimmy Rushing. -

John Mayfield

THE RECORDINGS OF JOHN MAYFIELD An Annotated Tentative Personnelo-Discography MAYFIELD, John, trombonist (previously known as ‘Masefield’) few biographical details known John Mayfiled played trombone with Ford Dabney´s Orchestra at the Roof (Ziegfeld´s Follies) from c. 1921 on and was with Jack Hatton andd his Novelty Band in 1922, but switched from trombone to reeds about 1925. Has returned to trombone in 1928 (NYA 7/7/28 7/3). In 1930 he played with Joe Jordan´s musical production ‘Brown Buddies’. Occasionally listed incorrectly as John Masefield. (Storyville 2002-3, p.198, Pieces of the Jigsaw) STYLISTICS STYLE John Mayfield plays a trombone style rooted in New Orleans tailgate style (there are phrases that remind me in Kid Ory) as well as in a more melodic and legato Northern style. TONE He owns a strong and clear tone showing him being a legitimate and reading musician. He also likes to climb up into higher register of his instrument, sometimes. VIBRATO Close to no vibrato, thus vebrato extremely slow and with minimal altitude, if at all. TIME Exact and strong time, but without swing. PHRASING As he almost entirely plays in ensemble parts – and seldom only performs as an instrumental soloist – there are a few improvised solos only to judge his phrasing abilities. He mostly plays harmonic legato counter-parts to the other horn men. But when heard in soloistic portions he mixes legato parts when intermediate short staccato phrases. This personnelo-discography is based on RUST, JAZZ AND RAGTIME RECORDS 1897 - 1942. Personnels are taken from this source, but modified in the light of earlier or subsequent research or on the strength of my own listening, discussed with our listening group or other interested collectors.