Minority Ethnic Language and Achievement Project Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adopting & Embedding Proven Practices & Approaches: Case

Adopting & Embedding Proven Practices & Approaches Case Studies Arising from the National HE STEM Programme ‘Menu of Activities’ Initiative Compiled and Edited by Michael Grove and Les Jones Adopting & Embedding Proven Practices & Approaches Case Studies Arising from the National HE STEM Programme ‘Menu of Activities’ Initiative Compiled and Edited by Michael Grove and Les Jones Copyright Notice These pages contain select synoptic case studies from the National HE STEM Programme ‘Menu of Activities’ Initiative which was launched in two stages in Autumn 2010 and Spring 2011. Their development has been supported by members of the National HE STEM Programme Team and they incorporate final reports, case studies and other information provided by the respective project leads throughout the duration of their projects. The included case studies have been edited by the Editors to ensure a consistent format is adopted and to ensure appropriate submitted information is included. The intellectual property for the material contained within this document remains with the attributed author(s) of each case study or with those who developed the initial series of activities upon which these are based. All images used were supplied by project leads as part of their submitted case studies. Adopting & Embedding Proven Practices & Approaches: Case Studies Arising from the National HE STEM Programme ‘Menu of Activities’ Initiative is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. © The University of Birmingham on behalf of the National HE STEM Programme ISBN 978-0-9567255-6-1 March 2013 Published by University of Birmingham STEM Education Centre on behalf of the National HE STEM Programme University of Birmingham Edgbaston Birmingham, B15 2TT www.hestem.ac.uk Acknowledgments The National HE STEM Programme is grateful to each project lead and author of the case study for their hard work and dedication throughout the duration of their work. -

Review of Secondary Education Provision in the Mid and North West of Pembrokeshire

REVIEW OF SECONDARY EDUCATION PROVISION IN THE MID AND NORTH WEST OF PEMBROKESHIRE CONSULTATION DOCUMENT March 2015 Contents Foreword Introduction What is the Council’s proposal? What is consultation? Who we will consult with? How you can respond to this consultation Consultation arrangements Summary of the Statutory Process Section 1 – The Case for Change Educational Standards Welsh Medium Education Additional Learning Needs Provision Post 16 Funding and Progression Surplus Places Condition & Suitability of Buildings Section 2 – Appraisal of the Options Section 3 – The proposed changes to secondary provision in Haverfordwest and to the catchment area for Milford Haven Secondary School Section 4 – The proposed changes to sixth form provision Section 5 – The proposed changes to Welsh medium provision Section 6 – The proposed addition of secondary Learning Resource Centres in Haverfordwest and Fishguard Section 7 – Proposed Changes – General Matters Section 8 – Impact Assessments Section 9 – Statutory Consultation Response Form Introduction Foreword Pembrokeshire County Council is responsible for promoting high educational standards and for delivering efficient primary and secondary education. Having the right schools in the right places and ensuring that they are fit for our 21st century learners is a challenge facing us, and all councils across Wales. Meeting this challenge involves reviewing the number and types of school the Council has in its area, and assessing whether or not best use is being made of its resources and facilities. The Council reviews its provision on the basis of: Quality and future sustainability of educational provision Sufficiency and accessibility of school places The condition, suitability and standard of school buildings Value for money This consultation document sets out the case for change to secondary education provision in the Mid and North West areas of Pembrokeshire and outlines the Council’s preferred option. -

October 2018

www.solvanews.co.uk October 2018 Issue # 119 “Solfach yn Cofio” “Solva Remembers” On Saturday 10 November in Solva Memorial Hall a “Street Party” will be held to commemorate the centenary of the signing of the armistice. We hope many of you will choose to join in the event. There will be 100 places available and a list will reside in Bay View Stores between 6 October and 6 November. Please sign and take one ticket per person. The ticket will entitle the bearer to join in an evening of drama, music, poetry, comedy, singing and dancing. The places will be allocated on a first come first served basis. Period dress is optional. There is no charge for this special entertainment. Instead we ask that you bring with you a paper plate of something savoury to share and any favourite tipples!! Tea, coffee and soft drinks will be available and cakes and sweet treats will be provided. If you would be interested in contributing further there will be a cooking workshop on the morning of 10 November in the Memorial Hall, led by the WI. (9.30 am -12.30 pm); that afternoon there will be a craft workshop (2.00 - 5.00 pm) to make decorations for the Main Hall and to help lay the tables for the evening's performance. All welcome, even if you can't make the show. In keeping with the traditions of WW1 “Welcome Home” street parties there will be a contribution box in the shop for flour, butter, sugar, dried fruit etc. Street parties were a community affair. -

Schools in Pembrokeshire / Ysgolion Yn Sir Benfro 2017

Details correct as at 1st September 2017 Manylion yn gywir fel ar 1 Medi 2017 Schools in Pembrokeshire / Ysgolion yn Sir Benfro 2017 School Number on Address Roll Number of Number of Headteacher School number School (FTE) Admission Applications (Successful) Admission Telephone (Pembrokeshire Language Age Capacity January Number for places Appeals for Number e-mail code = 668) Cluster of Schools Category Range 2017 2017 2017/18 2017/18 2017/18 2018/19 Ysgol Nifer Cyfeiriad Disgyblion Nifer Pennaeth Rhif yr Ysgol (CAL) Rhif Geisiadau Nifer o Apelau Ffôn (cod Sir Clwstwr Categori Cynhwysedd Ionawr Mynediad am Lefydd (Llwyddiannus) Rhif Mynediad e-bost Benfro = 668) Ysgolion laith Oedran 2017 2017 2017/18 2017/18 2017/18 2018/19 Explanatory note / Nodyn esboniadol 1 2 3 4 5 6 4 Greenhill / Tenby The Greenhill School 4035 Greenhill EM 11-18+ 1287 913 209 133 0 214 Heywood Lane / Lon Heywood (Tenby) Tenby / Dinbych-y-Pysgod SA70 8BN Mr R McGovern 01834 840100 [email protected] Manorbier Church in Wales VC School 3042 Greenhill EM 3-11 86 55.5 12 5 0 12 Manorbier / Maenorbyr (Tenby) Tenby / Dinbych-y-Pysgod SA70 7SN Mrs S Davies 01834 871228 [email protected] Narberth Community Primary School 2242 Greenhill DS 3-11 330 294.5 47 39 0 47 Jesse Road (Tenby) Narberth / Arberth SA67 7FE Mrs N Ward 01834 860776 [email protected] Sageston Community Primary School 2203 Greenhill EM 3-11 120 124 17 13 0 17 Sageston (Tenby) Tenby / Dinbych-y-Pysgod SA70 8SH Mrs J Morris 01646 651471 [email protected] -

Ysgol Penrhyn Dewi for Providing Teas, Coffee’S and Cakes at the Awards Evening and for Supporting a Number of Other Recent Events

12th April 2019 Dear Parent /Carer I would like to once again express my heartfelt thanks to you all for your excellent support during the second half of the Lent term. It has been a busy time for the school since I last wrote to you and I am delighted to report that the school has continued to grow with our pupils being involved a wide range of activities. Thanks to all parents/carers of the primary phase for supporting the recent ‘Play –Streets’ walk /cycle/scoot to school initiative. We were only one of two schools in the whole of Wales to take part in the event and our pupils thoroughly enjoyed having access to the front of the school as the gates were closed for the day. On so many levels the event was so positive, from reducing air pollution, improving safety around the school and encouraging healthy lifestyles. The pupils really enjoyed the day and the response from them exceeded all of our expectations. I was delighted to see the children celebrating the re-scheduled 10 year anniversary of the Dragon Lantern Parade in St Davids on Saturday 6th April and I would like to take this opportunity to thank Elly Morgan, lead artist from the National Park Authority, for assisting the pupils in making their lanterns for this event. We would also like to thank the community of St Davids for providing all of the milk cartons for our pupils to make their beautiful lanterns. Many thanks also to Dr Sam Langdon for introducing the Adders are Amazing initiative to the school. -

New Schools Open Thanks to £70M+ Investment

New Schools Open Thanks To £70m+ Investment Three brand new secondary schools are set to open in the County this week, thanks to an investment of more than £70 million by Pembrokeshire County Council and the Welsh Government. Welcoming hundreds of pupils through their doors for the first time are Ysgol Harri Tudur/ Henry Tudor School in Pembroke; Ysgol Caer Elen in Haverfordwest and Ysgol yr Eglwys yng Nghymru Penrhyn Dewi in St Davids. The schools are part of the 21st Century Schools investment programme run by the County Council in collaboration with the Welsh Government. Darren Thomas, Programme Manager and the Council’s Head of Infrastructure, said he was delighted that the three major projects had been delivered successfully. “We’d like to thank the staff, governing bodies and local communities of the three schools who have undertaken a tremendous amount of work to ensure that the new schools have opened on time and within budget,” he said. Ysgol Harri Tudur / Henry Tudor School is an entirely new build on the Bush school site in Pembroke, accommodating all pupils from the former Pembroke School. The flagship project cost £38.3 million and is the largest ever project undertaken by the County Council. The 11-19 secondary school was built by construction company Bouygues UK and provides education for 1,463 children and an autism centre for 30 learners. Work will now begin to demolish the old Pembroke School and the former Pembroke Grammar School buildings, with the aim of completing all work on site by August, 2019. Headteacher Fiona Kite said: ''Last year we held a competition among staff and students to create a motto for our new school. -

Regional Hubs: Contact Details for Schools, Parents and Carers

Seren Network – Regional Hubs Contact Details for Schools, Parents and Carers Bridgend The Bridgend hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Archbishop McGrath Catholic School Brynteg School Bryntirion Comprehensive School Coleg Cymunedol Y Dderwen Cynffig Comprehensive School Maesteg School Pencoed Comprehensive School Porthcawl Comprehensive School Ysgol Gyfun Gymraeg Llangynwyd For further information on the Bridgend hub (Years 8-13), please contact the hub coordinator, Simon Gray: [email protected] Cardiff The Cardiff hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Pre-16 provision only Includes post-16 provision Corpus Christi Catholic High Bishop of Llandaff Church in School Wales High School Eastern High School Cantonian High School Mary Immaculate High School Cardiff High School St Illtyd’s Catholic High School Cardiff West Community High School Willows High School Fitzalan High School Llanishen High School Radyr Comprehensive School 27/05/2020 1 St Teilo’s Church in Wales High School Whitchurch High School Ysgol Bro Edern Ysgol Glantaf Ysgol Plasmawr Post-16 provision only Cardiff and Vale College St David’s College For further information on the Cardiff hub (Years 8-13), please contact the hub coordinator, Jo Kemp: [email protected] Carmarthenshire, Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire The Carmarthenshire, Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire hub is made up of the following partner schools and colleges: Pre-16 provision only Includes post-16 provision Ysgol Bro Gwaun -

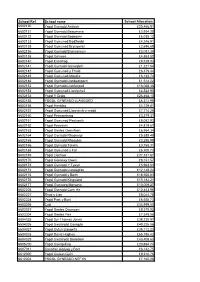

School Ref School Name School Allocation 6602130 Ysgol Gynradd

School Ref School name School Allocation 6602130 Ysgol Gynradd Amlwch £20,466.91 6602131 Ysgol Gynradd Beaumaris £3,934.20 6602132 Ysgol Gynradd Bodedern £6,038.12 6602133 Ysgol Gymuned Bodffordd £4,246.91 6602135 Ysgol Gymuned Bryngwran £2,696.68 6602136 Ysgol Gynradd Brynsiencyn £3,081.38 6602138 Ysgol Cemaes £4,853.52 6602140 Ysgol Esceifiog £8,529.83 6602141 Ysgol Gynradd Garreglefn £1,221.54 6602142 Ysgol Gymuned y Ffridd £6,379.44 6602145 Ysgol Gymuned Moelfre £6,122.74 6602146 Ysgol Gynradd Llanbedrgoch £1,514.22 6602152 Ysgol Gynradd Llanfairpwll £16,068.36 6602153 Ysgol Gymuned Llanfechell £4,543.90 6602154 Ysgol Y Graig £26,468.10 6602155 YSGOL GYNRADD LLANGOED £6,312.95 6602156 Ysgol Henblas £4,729.81 6602157 Ysgol Gymuned Llannerch-y-medd £7,774.26 6602160 Ysgol Pencarnisiog £3,379.31 6602161 Ysgol Gymuned Pentraeth £8,082.93 6602162 Ysgol Penysarn £4,819.67 6602163 Ysgol Santes Gwenfaen £6,954.34 6602164 Ysgol Gynradd Rhosneigr £5,355.49 6602165 Ysgol Gynradd Rhosybol £3,298.99 6602166 Ysgol Gynradd Talwrn £3,768.31 6602168 Ysgol Gymuned y Fali £6,700.73 6602169 Ysgol Llanfawr £27,331.67 6602170 Ysgol Goronwy Owen £8,151.57 6602173 Ysgol Gynradd Y Tywyn £5,963.03 6602174 Ysgol Gynradd Llandegfan £12,148.24 6602175 Ysgol Gynradd y Borth £18,565.83 6602176 Ysgol Gynradd Kingsland £15,182.21 6602177 Ysgol Gymraeg Morswyn £10,009.27 6602226 Ysgol Gynradd Corn Hir £10,843.96 6602227 Rhyd y Llan £8,044.78 6602228 Ysgol Parc y Bont £6,925.73 6603036 Cybi £35,999.05 6603037 Ysgol Santes Dwynwen £9,370.02 6603304 Ysgol Santes Fair -

NEWYDDION DINAS TYDDEWI ST DAVIDS CITY NEWS Gwanwyn 2016 Spring Community Award for Paul Edey

NEWYDDION DINAS TYDDEWI ST DAVIDS CITY NEWS Gwanwyn 2016 Spring Community Award for Paul Edey Paul Edey was the winner of this year’s Community Award. The Mayor, Councillor Frank John, presented him with his winning certificate at this year’s Christmas Civic Reception at the City Hall. Paul is Vice Chair of the St Davids and Dewisland Historical Society, Chair of St Davids Community Forum and an active member of the Friends of Oriel Y Parc. The event was attended by representatives of a large number of different organisations in St Davids. Music was provided by Ysgol Dewi Sant Brass Ensemble. Ysgol Bro Dewi pupils perform their Nativity play The pupils of Ysgol Brow Dewi performed their Nativity play at the City Hall for the annual Senior Citizens Christmas Lunch. Please see page 4 and 5 for reports of other Christmas events. Letter from the Mayor, Cllr Frank John Since my last letter the The contractors were extremely efficient in completing all the situation at Ysgol Dewi Sant work on time and I extend my thanks to them for a job well has become much clearer, done. with the publication of the statutory notices confirming We are also delighted that the Day Centre has been able to the future plans for the move to the Memorial Hall for its regular events. In my last schools in our peninsula. letter I referred to the need for us to take on responsibility for The first credit for all this has the flower beds in the city. We are planning to hold a meeting to go to all of you who came to to discuss this further. -

September 2014 in the Council Chamber at 7.00Pm

CYNGOR DINAS TYDDEWI ST DAVIDS CITY COUNCIL Minutes of the Monthly Meeting of the Council on Monday 1st September 2014 in the Council Chamber at 7.00pm Present: Mayor DB Halse, Deputy Mayor FD John, MC Gray, MGD James, JG Lloyd, K Rose, CT Taylor, S Williams with CH Gray (Clerk) and PL Evans (Responsible Finance Officer). Also present was County Councilor DB Lloyd. 212 Apologies for Absence: DJO Chant, ES Evans, DJH George, BT Price. 213 Declarations of Interest: Members were requested to identify any declarations of personal or prejudicial interests that they might have in relation to items on the agenda. 213.1 Cllr John declared a prejudicial interest in relation to Item 253 and left the chamber while the item was discussed. 214 Confirmation of Minutes for:- 214.1 The Council Monthly Meeting on Monday 7th July 2014 were RESOLVED to be approved. 214.2 "In Committee" Meeting of the Council Monthly Meeting on Monday 7th July 2014 were RESOLVED to be approved. 214.3 The Second Meeting of the Month on Monday 21st July 2014 were RESOLVED to be approved. 214.4 The Special Meeting of the City Council on Monday 25th July 2014 were RESOLVED to be approved. 214.5 The Special Meeting of the City Council on Wednesday 6th August 2014 were RESOLVED to be approved. Matters Arising 215 CITY COUNCIL YOUTH REPRESENTATIVES The Mayor reported that he had spoken to the Headteacher at Ysgol Bro Dewi and was also due to speak with the Headteacher of Ysgol Dewi Sant to discuss the possibility of establishing a link between the City Council and the school councils. -

Contractors on Site at Ysgol Dewi Sant As Rebuild Begins

NEWYDDION DINAS TYDDEWI ST DAVIDS CITY NEWS Hydref 2017 Autumn Contractors on site Fun Day a great success at Ysgol Dewi Sant as rebuild begins Contractors have already moved onto the Ysgol Dewi Sant site to start the rebuilding of the school in preparations for its re-opening as a 3 - 16 VA school in September of next year. The £4 million scheme has been awarded to the Haverfordwest based company W. B. Griffiths and Son Limited, following evaluation by Pembrokeshire County Council of tendered prices. The arrival of the contractors follows a period of intense activity at the school at the end of the academic year which saw the removal of furniture and contents to the school’s temporary home at Tasker Milward School in Haverfordwest. Some of the remaining equipment has been temporarily stored in Ysgol Dewi Sant’s school hall which is not directly involved in the rebuild. The school has meanwhile been made into a secure site, with asbestos experts currently testing and sampling the situation with a view to removing all asbestos from the buildings which are to be demolished. This process should take place in the next few weeks, while necessary permissions for the work are organised. The Fun Day was organised by six Carnival Committee enthusiasts, with the winners of the fancy dress competition Meanwhile preparations for the school’s being Efa Harries and Harri Chant. There was plenty of fun temporary residence in Haverfordwest were all and games on the day including a hotly contested Tug of War completed in time for the beginning of the new competition, which this year was won by the boys 2-1! There school year, with IT infrastructure and telephone was also rugby fun and games on the day, which was won by systems installed at the Milward site, and Torbant Caravan Park All Stars. -

Elective Home Education (EHE)

Elective Home Education (EHE) Nichola Jones Head of Inclusion and Disabilities 1 INTRODUCTION Elective Home Education (EHE) is where a parent elects to take personal responsibility for their child’s educational provision, including both planning and delivering an educational programme. This is often referred to as “Elective Home Education” or “education otherwise” as in Section 7 of the 1996 Education Act. The primary duty to educate a child rests with parents and for most children this means that they will normally go to school, but for various reasons some parents decide to undertake the responsibility of educating their children outside the school system. It is important for you to think about why you are considering Elective Home Education. Effective home education requires commitment along with patience and perseverance and your decision could have major implications on your child’s future. Pembrokeshire County Council (PCC) recognises and respects the right of parents/ carers to educate their children at home and is committed to working with parents/ carers. Our aim is to ensure that families are aware of the services that are available locally and that you know how to access them. There are a number of parents who want an alternative to school and the Local Authority (LA) endeavours to ensure that your child has the best possible opportunity for learning and support during their period of elective home education. Pembrokeshire Local Authority will seek to work cooperatively with elective home educating parents to encourage communication networks and supportive working within and between the local EHE groups and individuals; At times you may need support in understanding your role, and we may need to give you the opportunity to present evidence of your child’s learning experience to demonstrate your child’s continuing educational progress.