Assessment of Norway's Public Procurement System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 Rule of Law Report | SGI Sustainable Governance Indicators

Sustainable Governance Indicators SGI 2014 Rule of Law Report Legal Certainty, Judicial Review, Appointment of Justices, Corruption Prevention SGI 2014 | 2 Rule of Law Report Indicator Legal Certainty Question To what extent do government and administration act on the basis of and in accordance with legal provisions to provide legal certainty? 41 OECD and EU countries are sorted according to their performance on a scale from 10 (best) to 1 (lowest). This scale is tied to four qualitative evaluation levels. 10-9 = Government and administration act predictably, on the basis of and in accordance with legal provisions. Legal regulations are consistent and transparent, ensuring legal certainty. 8-6 = Government and administration rarely make unpredictable decisions. Legal regulations are consistent, but leave a large scope of discretion to the government or administration. 5-3 = Government and administration sometimes make unpredictable decisions that go beyond given legal bases or do not conform to existing legal regulations. Some legal regulations are inconsistent and contradictory. 2-1 = Government and administration often make unpredictable decisions that lack a legal basis or ignore existing legal regulations. Legal regulations are inconsistent, full of loopholes and contradict each other. Estonia Score 10 The rule of law is fundamental to Estonian government and administration. In the period of transition from communism to liberal democracy, most of the legal acts and regulations had to be amended or introduced for the first time. Joining the European Union in 2004 caused another major wave of legal reforms. These fast and radical changes, which occurred in a short timespan, caused some inconsistencies and unexpected legal amendments (for example the increase of the VAT in 2009). -

Hetland 1957 – 1958

'46 HESKESTAD HERRED (Heskestad p.A.-Ualandf) HESKESTAD HERRED (Uala.nd) -HETLAND HERRED '" Hesk.estBd Handelslag, 12,000, O, best P Randa BllstBd, Om. T O, gbr., 18,000, 7700 Svale, gbr., 36,000, 11,700 Ueland, Jonas J, gbr., bankkass., lIgn.sjef, RefsIand, - Jacob, hj.lærer, 0, 4000 . - Ommund Th., gbr. 40,000, 14,200 - TorvaJl, gbr., 16,000, 0100 33,000, 9200 Reinertsen, Ablgal, gbr., Ollesl.ad, 17,000, 54,000, - Johs" gbr.• 39,000. 14,200 - ottar, gbr., 24,000, 8700 -Kjell, gbr., 13,400 1000 - Margit, gbr., 26,000, 2200 _ Sigmund, gbr., 109,000, 14,600 - Kristine P, hush., 15,000, 1200 - Bjame, baneform. 19,000, 10,600 , - Olav, lærer, Elde, 6000, 13,300 - Sigvart, aru.arb., 6000 14,100 - MartheG J, 5000 5600 , Magne, hdls.best.. 2000, 14,200 pens.,. 11,000, O - William, gbr., lærer 8000, 14,200 - Børen, gbr., 20,000, 14,000 - Martha pens RiSa, Hæver, Peder, banev., ,Mona, 1000, 8500 - TOTbJølll", butlkkd., O, 4300 Sirevlg, Alf, gbr., Tekse, 28,000, 6500 - OG S, gbr.,O, Hetland,. 26,000, 5200 Kristensen, Arne, anl.arb., Eide, 32,000, 12,700 BIrkemo, Konrad, 27,000, 2400 Sklpsæ,d, Tenny, anl.arb., BUstad, 12,000, - Olav, gbr., 68,000, 9800 Kvfnen, Arne, banev., Elde, O, 92(10 - NII's, gbr., 32,000,gbr., 2400 16,000 -Skole l.4Lnghus, Inga gbr., 20,000, 3100 - Qmmund, gbr .. 31,000, 9000 - n-ygve, arb., BUstad, 14,000, 5300 -Svein J, gbr., Ollestad, 50,000, 9400 -Trygve, gbr", 28,000, 3200 Bjuland, Knut, gbr., 51,000, 25,800 Skjerpe, Martine, kArm., 15,000, O - Sven A, gbr., 42,000, 16,500 , Mol, gbr., Eide, 18,000, 530{) BjØrnemo, Tønnes S, gbr., 30,000, 8000 - Peder, gbr., 34.000, 11,800 -Øyvind, gbl·., Het.hlnd, 19,000, 12,800 3000 SlettebØ,Arthur, banev.,Refsland, O, 9500 VassbØ, Ingvald, sjåfØr, Olle8tad, 16,000, 2400 . -

Uden Haugianernes Assistance Kan Ikke En Præst Udrette De Stor Ting"

SHP, Høgskulen i Volda: Kulturperspektiv på møte mellom bønder og embetsmenn. Prosjektseminar 3.–4. september 2008 Svein Ivar Langhelle: "Uden Haugianernes Assistance kan ikke en Præst udrette de stor Ting" I perioden 1820 til 1850 skjedde relativt dramatiske endringar av livsførselen på Sørvestlandet parallelt med at haugianismen vann stort innpass gjennom omfattande religiøse vekkingar. Dette galdt også blant dei som stod utanfor vekkingane. Noko av det som elles var lettast å få auge på, var nye skikkar kring fest og samkomer, arbeid på heilagdagar, deltaking i hussamlingar og andre religiøse møte, samt bruk av religiøs litteratur.1 Eg går berre ganske kort inn på dette nå og lar det stå som eit bakteppe til det eg skal leggja fram. Eg vil her særleg sjå på noko av det som skjedde i Nord-Rogaland. I 1854 summerte presten Johan Peter Berg opp forholda i Skjold prestegjeld. Sjølv om talet på haugianarar i prestegjeldet ikkje var “meget stort” og dei “vakte” var i mindretal, var stemninga sterkt påverka av haugiansk pietisme. Omgangstonen mellom folk var prega av alvor og stille framferd, dei snakka og lo ikkje høgt. Folk gjekk og rei fort berre i nødsfall. Plystring, moroskap, utbrot av glede, sinne eller iver var teikn på at ein var eit “Verdensbarn” og gjorde at vedkomande ble “udsat for Mistanke og Omtale”.2 Avaldsnes var, ved sida av Vikedal, det prestegjeldet i Nord-Rogaland som då var minst prega av haugianismen. Likevel ser me at prost Sinding i Avaldsnes i 1853 skriv at ”Enkelte Mænd… have haft en Slags Fuldmagt til at fungere som Paamindere og Raadgivere i aandelige Ting… Almuens Skikke og Tankemaade i det Hele taget er ikke lidet paavirket af Haugianismen”, og at det derfor var vanskelig å ”afgive noget brugbart Skjelnemærke mellem Haugianere og Ikke-Haugianere”.3 Hans Nielsen Hauge var sjølvsagt svært viktig som ideologisk kraft og førebilde for dei lokale haugianarane, men på det lokale planet var det John Haugvaldstad frå Rennesøy og Stavanger som var høvdingen og den absolutt mest sentrale haugianaren. -

Business Corruption: Incidence, Mechanisms, and Consequences

Business corruption: Incidence, mechanisms, and consequences Tina Søreide Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) Thesis submitted for the degree of dr. oecon at the Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration (NHH) Bergen, Norway 9 February 2006 Acknowledgments A PhD study is an individual activity and responsibility. During this study, however, I have benefited from constructive feedback and support. I have met a large number of interesting people, and I have been working in a friendly and stimulating atmosphere at Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI). Kjetil Bjorvatn has guided me through the process. Repeatedly I was impressed by his combination of critical comments and humor. I am very grateful for his understanding, as well as his comprehensive and rapid response. I also got the benefit of working with two excellent supervisors, Kalle Moene and Susan Rose-Ackerman. Their opinions and corrections have been important, and I have truly appreciated their friendly attitude. My stay as a visiting scholar at Yale University during the spring of 2003 was inspiring, and I wish to thank Susan for inviting me. The PhD study, the stay in New Haven included, has been financed by the Norwegian Research Council, and I am very grateful for their support. The Confederation of Norwegian Enterprise (NHO) gave me substantial backing and encouragement during my empirical studies. I wish to thank them a lot. I will also express gratitude to the survey interviewees and respondents who supported my project with their time and their confidence. The study would not have been started without encouragement from Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Hildegunn Kyvik Nordås, Arve Ofstad, and support from the CMI administration. -

NR. 4 September 2020 ÅRGANG 62 Kyrkjeblad for Bjoa, Imsland, Sandeid, Skjold, Vats, Vikebygd, Vikedal Og Ølen

OFFENTLEG INFORMASJON NR. 4 September 2020 ÅRGANG 62 Kyrkjeblad for Bjoa, Imsland, Sandeid, Skjold, Vats, Vikebygd, Vikedal og Ølen Gudsteneste på Romsa, sjå side 6 Kateketen har ordet 2 Springing gjev pusterom! 4 Framleis rom i kyrkja 8 Hausten 2020 2 Bjoa kyrkje 125 år 5 Frå kyrkjeboka 8 Redaksjonspennen 3 Oppgradering av Bjoa kyrkje 5 Gundstenester 10 Tradisjon i 120 år 3 Gudsteneste på Romsa 6 Møte og arrangement 11 Orgelet i Vats kyrkje 100 år 3 Kva er kyrkja? 7 Inspirasjonssamling 12 Konfirmantar Bjoa og Ølen 5 Endeleg søndag på Kårhus 7 1 Redaksjons- Kateketen har ordet Britt Karstensen, kateket. PENNEN Av Steinar Skartland HYRDINGEN: Kyrkjeleg fellesråd har gjennom fleire Ansvarleg: Steinar Skartland år fått ekstra midlar av kommunen Tlf. 908 73 170 Ikkje som planlagt til oppgradering av kyrkjene. Den 8. Epost: [email protected] kyrkja som får gleda av dette er på Bjoa. Bladpengar/gåver til Hyrdingen Det blei plutseleg travelt med haust- Å konfirmera tyder å stadfesta. I Ekstra midlane er redusert vesentleg på konto: 3240.11.17937 og konfirmasjonar i år. Sånn blir det, når konfirmasjonen stadfester Gud gåva i nå, men fellesråd og kyrkjeverje VIPPS nr 53 14 72 ting ikkje går som planlagt. Kanskje dåpen, at me får vera Hans born, at prioriterer bygg og kyrkjegardar så Adr. Skjold kyrkje var det like greitt for nokon, kanskje Han framleis vil vera nær. Sånt sett godt det let seg gjera for å sikra at Kleivavegen 2, 5574 Skjold blei det litt mykje stress for andre, men kan ein nesten seie at me ALLE «blir kyrkjene òg i framtida skal vera tenlege Hans Asbjørn Aasbø talar på ettermiddagsmøtet. -

Table of Contents

CMIREPORT Collaboration on Anti-Corruption Norway and Brazil Tina Søreide and Claudio Weber Abramo R 2008: 1 Collaboration on Anti-Corruption Norway and Brazil Tina Søreide and Claudio Weber Abramo R 2008: 1 CMI Reports This series can be ordered from: Chr. Michelsen Institute P.O. Box 6033 Postterminalen, N-5892 Bergen, Norway Tel: + 47 55 57 40 00 Fax: + 47 55 57 41 66 E-mail: [email protected] www.cmi.no Price: NOK 50 Printed version: ISSN 0805-505X Electronic version: ISSN 1890-503X Printed version: ISBN 978-82-8062-227-3 Electronic version: ISBN 978-82-8062-228-0 This report is also available at: www.cmi.no/publications Cover photo: Isabel Pauletti Indexing terms Project number 27069 Project title Collaboration on Anti-Corruption - Norway and Brazil CMI REPORT COLLABORATION ON ANTI-CORRUPTION R 2008: 1 About the authors Tina Søreide is a Norwegian economist at Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI), an independent research institute based in Norway. Claudio Weber Abramo is the executive director of Transparência Brasil, an NGO dedicated to combating corruption in Brazil. About this report Much has been said about anti-corruption initiatives, about the causes and consequences of corruption, and about what governments can do to combat this problem. Most discussions and policy recommendations focus on what governments can do within their jurisdictions. This report takes a different approach by exploring how countries and players can combat corruption through cross-border collaboration. Bilateral collaboration and Norwegian presence in Brazilian markets The report argues that the fight against corruption needs stronger transnational cooperation and attempts to map out issues that might be relevant for such collaboration. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2 015 COPY LAYOUT PHOTOS the Norwegian Bureau Newmarketing AS Lars A

ANNUAL REPORT 2 015 COPY LAYOUT PHOTOS The Norwegian Bureau Newmarketing AS Lars A. Lien for the Investigation of Tore Letvik, Juristkontakt Police Affairs PRINT Politiforum PJ-trykk, Oslo iStock Photo Police Inspectorate of Kosova Thomas Haugersveen, Politiforum CONTENTS Foreword 3 The 10th Anniversary of the Bureau 4 Police Ethics 6 Investigation of Police Shootings 8 Accidental Shootings 10 Misuse of Police Records 12 Dealing with Requests for Assistance 14 International Cooperation in 2015 16 Necessary for or Considerably Facilitating Performance of Duty 18 New Provisions concerning Offences Committed in the course of Official Duty 20 Statistics 2015 22 Decisions to Prosecute 2015 26 Court Cases 2015 32 Emergency Turn-outs 2015 34 Administrative Assessments 2015 36 The Bureau’s Organisation and Staffing 38 Who Works at the Bureau – The Director of the Bureau 40 241 651 Who Works at the Bureau? – The Investigation Divisions 42 Trykksak Articles from Previous Annual Reports 46 Both the police and society at large undergo continual change. It is important for the Bureau to maintain a level of professionalism that enables assignments to be dealt with thoroughly and efficiently and as independently as possible. FOREWORD n several of its annual reports, the days, but the average processing time in Bureau has drawn attention to ques- 2015 was 204 days. The increase from 2014 I tions concerning deprivation of to 2015 was expected, and was brought liberty and the use of police custody. This about by the need to delay investigations was also a major topic when the Bureau and other processing in a number of commemorated 10 years of operation in cases owing to work on the above case May 2015. -

Dalbygda Vindkraftverk I Tysvær Kommune, Rogaland Fylke

Dalbygda vindkraftverk i Tysvær kommune, Rogaland fylke. Konsekvensutredning. Tema Landskap Indre deler av Vatsfjorden. Foto: Morten W. Melby Melby, M. W. 2012. Dalbygda vindkraftverk i Tysvær kommune, Rogaland fylke. Konsekvensutredning. Tema Landskap. Miljøfaglig Utredning rapport 2012-36, ISBN 978-82-8138-609-9. Dalbygda vindkraftverk i Tysvær kommune, Rogaland fylke K ONSEKVENSUTREDNING . T E M A L ANDSKAP Miljøfaglig Utredning AS Rapport 2012:36 Prosjektansvarlig: Morten Wewer Melby Utførende institusjon: Miljøfaglig Utredning AS Prosjektmedarbeider(e): Oppdragsgiver: Kontaktperson hos oppdragsgiver: Dalbygda Kraftsenter AS Øyvind Hellerslien Referanse: Melby, M. W. 2012. Dalbygda vindkraftverk i Tysvær kommune, Rogaland fylke. Konsekvensutredning. Tema Landskap. Miljøfaglig Utredning rapport 2012-36, ISBN 978- 82-8138-609-9. Referat: Miljøfaglig Utredning AS har bistått Dalbygda Kraftsenter AS med å utarbeide tematisk konsekvensutredning i forbindelse med deres planer om bygging av et vindkraftverk nordøst for Dalbygda i Skjoldastraumen i Tysvær kommune, Rogaland. Denne rapporten omhandler tema Landskap, peker på viktige kvaliteter innenfor tiltakets influensområde (utredningsområdet), vurderer konsekvenser av tiltaket og anbefaler avbøtende tiltak. Planene opererer med ett utbyggingsalternativ, hvor 13 vindturbiner (2,0-3,0 MW) med navhøyde 60-80 m, rotordiameter 90 m og med en innbyrdes avstand på 5-600 m, plasseres på et sammenhengende høydedrag øst for Dalbygda i høydelaget 300-420 m oh. Et stort antall av vindturbinene vil være særlig godt synlige fra vest, men også fra enkelte høyereliggende partier i nord, øst og sør. Utredningsområdet er delt inn i 7 enhetlige landskapsområder som er beskrevet i henhold til anbefalt metode. Beskrivelsene og andre registreringer begrunner fastsettelsen av en landskapskarakter og verdisettingen for hvert enkelt delområde. -

Det-Norske-Myrselskap-1949

MEDDELELSER FRA DET NORSl(E MYRSELSl(AP Nr. 6 Desember 1949 47. årgang Redigert av Aasulv Løddesøl. MYRENE I KYSTHERREDENE I NORD-ROGALAND. Av konsulent Ose. Hovde. Nord-Rogaland er vanlig benevnelse for den del av Rogala,nd fylke som ligger nord for Boknafjorden. De typiske kystherreder i Nord-Rogaland - regnet nordfra -- er følgende 8: Skåre, Torvastad, Avaldsnes, Utsira, Åkra, Stangaland, Skudenes og Bokn. Innen dette kystområde ligger også 3 bykommuner, nemlig Haugesund, Kopervik og Skudeneshavn. Nærmere geografisk bestemt ligger disse herreder mellom 59°08' og 59°31' nordlig bredde og mellom 5~10' og 6° vestlig lengde (Oslo meridian). Herredenes totalareal er 407,96 km2 og land• arealet 392,02 km2• Av hele Rogaland fylke utgjør dette område 4,50 %. Det meste av Skåre og Avaldsnes herreder med Haugesund by og en mindre del av Torvastad ligger på fastland (Haugalandet), men for øvrig ligger de andre herreder på øyer. Den største av disse er Karmøya. Her ligger de tre herreder Skudenes, Akra og Stanga• land i sin helhet og dessuten det meste av Torvastad og en del av Avaldsnes. Her er dessuten de to bykommuner Kopervik og Skude·• neshavn. Karmøya er således Norges folkerikeste og tettest bebodde øy. Bokn herred ligger på flere øyer øst for Karmøya, og Utsira her• red ligger langt ute i havet (16 km) rett vest av Karmøya, Kommunikasjonene innen området er stort sett gode, men den svære trafikk over Karmsundet ·gjør krav om bru eller bedre ferje• forbindelse berettiget. Ruten på Karmøya trafikeres med busser av Norges Statsbaner. F j e 11 grunnen innen området består stort sett av 3 temmelig skarpt atskilte områder. -

Country Review Report of Norway

Country Review Report of Norway Review by Sweden and Kuwait of the implementation by Norway of articles 15 – 42 of Chapter III. “Criminalization and law enforcement” and articles 44 – 50 of Chapter IV. “International cooperation” of the United Nations Convention against Corruption for the review cycle 2010 - 2015 Page 1 of 142 Introduction 1. The Conference of the States Parties to the United Nations Convention against Corruption (hereinafter, UNCAC or the Convention) was established pursuant to article 63 of the Convention to, inter alia, promote and review the implementation of the Convention. 2. In accordance with article 63, paragraph 7, of the Convention, the Conference established at its third session, held in Doha from 9 to 13 November 2009, the Mechanism for the Review of Implementation of the Convention. The Mechanism was established also pursuant to article 4, paragraph 1, of the Convention, which states that States parties shall carry out their obligations under the Convention in a manner consistent with the principles of sovereign equality and territorial integrity of States and of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of other States. 3. The Review Mechanism is an intergovernmental process whose overall goal is to assist States parties in implementing the Convention. 4. The review process is based on the terms of reference of the Review Mechanism. II. Process 5. The following review of the implementation by Norway of the Convention is based on the completed response to the comprehensive self-assessment checklist received from Norway, and any supplementary information provided in accordance with paragraph 27 of the terms of reference of the Review Mechanism and the outcome of the constructive dialogue between Norway and the governmental experts from Kuwait and Sweden, by means of telephone conferences and e-mail exchanges and involving Dr. -

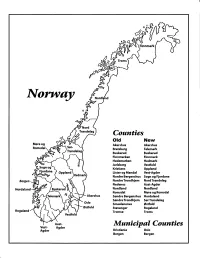

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Phase 3 Report on Implementing the Oecd Anti

PHASE 3 REPORT ON IMPLEMENTING THE OECD ANTI-BRIBERY CONVENTION IN NORWAY June 2011 This Phase 3 Report on Norway by the OECD Working Group on Bribery evaluates and makes recommendations on Norway’s implementation of the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions and the 2009 Recommendation of the Council for Further Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions. It was adopted by the Working Group on 23 June 2011. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................. 5 A. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 6 1. The on-site visit .................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Outline of the report.............................................................................................................................. 6 3. Economic Background.......................................................................................................................... 7 4. Cases involving the bribery of foreign public