Hepatitis C and Alcohol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hepatitis A, B, and C: Learn the Differences

Hepatitis A, B, and C: Learn the Differences Hepatitis A Hepatitis B Hepatitis C caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV) caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) HAV is found in the feces (poop) of people with hepa- HBV is found in blood and certain body fluids. The virus is spread HCV is found in blood and certain body fluids. The titis A and is usually spread by close personal contact when blood or body fluid from an infected person enters the body virus is spread when blood or body fluid from an HCV- (including sex or living in the same household). It of a person who is not immune. HBV is spread through having infected person enters another person’s body. HCV can also be spread by eating food or drinking water unprotected sex with an infected person, sharing needles or is spread through sharing needles or “works” when contaminated with HAV. “works” when shooting drugs, exposure to needlesticks or sharps shooting drugs, through exposure to needlesticks on the job, or from an infected mother to her baby during birth. or sharps on the job, or sometimes from an infected How is it spread? Exposure to infected blood in ANY situation can be a risk for mother to her baby during birth. It is possible to trans- transmission. mit HCV during sex, but it is not common. • People who wish to be protected from HAV infection • All infants, children, and teens ages 0 through 18 years There is no vaccine to prevent HCV. -

Active Peptic Ulcer Disease in Patients with Hepatitis C Virus-Related Cirrhosis: the Role of Helicobacter Pylori Infection and Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy

dore.qxd 7/19/2004 11:24 AM Page 521 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk ORIGINAL ARTICLE brought to you by CORE provided by Crossref Active peptic ulcer disease in patients with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis: The role of Helicobacter pylori infection and portal hypertensive gastropathy Maria Pina Dore MD PhD, Daniela Mura MD, Stefania Deledda MD, Emmanouil Maragkoudakis MD, Antonella Pironti MD, Giuseppe Realdi MD MP Dore, D Mura, S Deledda, E Maragkoudakis, Ulcère gastroduodénal évolutif chez les A Pironti, G Realdi. Active peptic ulcer disease in patients patients atteints de cirrhose liée au HCV : Le with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis: The role of Helicobacter pylori infection and portal hypertensive rôle de l’infection à Helicobacter pylori et de la gastropathy. Can J Gastroenterol 2004;18(8):521-524. gastropathie liée à l’hypertension portale BACKGROUND & AIM: The relationship between Helicobacter HISTORIQUE ET BUT : Le lien entre l’infection à Helicobacter pylori pylori infection and peptic ulcer disease in cirrhosis remains contro- et l’ulcère gastroduodénal dans la cirrhose reste controversé. Le but de la versial. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the role of présente étude est de vérifier le rôle de l’infection à H. pylori et de la gas- H pylori infection and portal hypertension gastropathy in the preva- tropathie liée à l’hypertension portale dans la prévalence de l’ulcère gas- lence of active peptic ulcer among dyspeptic patients with compen- troduodénal évolutif chez les patients dyspeptiques souffrant d’une sated hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related cirrhosis. -

Understanding Human Astrovirus from Pathogenesis to Treatment

University of Tennessee Health Science Center UTHSC Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations (ETD) College of Graduate Health Sciences 6-2020 Understanding Human Astrovirus from Pathogenesis to Treatment Virginia Hargest University of Tennessee Health Science Center Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uthsc.edu/dissertations Part of the Diseases Commons, Medical Sciences Commons, and the Viruses Commons Recommended Citation Hargest, Virginia (0000-0003-3883-1232), "Understanding Human Astrovirus from Pathogenesis to Treatment" (2020). Theses and Dissertations (ETD). Paper 523. http://dx.doi.org/10.21007/ etd.cghs.2020.0507. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Graduate Health Sciences at UTHSC Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (ETD) by an authorized administrator of UTHSC Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Understanding Human Astrovirus from Pathogenesis to Treatment Abstract While human astroviruses (HAstV) were discovered nearly 45 years ago, these small positive-sense RNA viruses remain critically understudied. These studies provide fundamental new research on astrovirus pathogenesis and disruption of the gut epithelium by induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) following astrovirus infection. Here we characterize HAstV-induced EMT as an upregulation of SNAI1 and VIM with a down regulation of CDH1 and OCLN, loss of cell-cell junctions most notably at 18 hours post-infection (hpi), and loss of cellular polarity by 24 hpi. While active transforming growth factor- (TGF-) increases during HAstV infection, inhibition of TGF- signaling does not hinder EMT induction. However, HAstV-induced EMT does require active viral replication. -

Hepatitis C 2005 Clinical Guidelines Summary of The: New York State Department of Health Clinical Guidelines for the Medical Management of Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C 2005 Clinical Guidelines Summary of the: New York State Department of Health Clinical Guidelines for the Medical Management of Hepatitis C Inside: Key Features of Viral Hepatitis A,B and C 1 Natural Course of HCV Infection 2 Persons at Risk for HCV Infection 3 Sources of HCV Infection 4 Counseling Prior To Testing 5 Screening for HCV Algorithm 6 Laboratory Testing for HCV 7 Interpretation of HCV Test Results 8 Post Exposure Screening for HCV 9 Counseling After Testing 10 Treating HCV Patients 11 Medical Management of HCV Positive Patients 12 References and Internet Resources 13 Hepatitis C Virus The Hidden Epidemic The Burden of HCV • 3 million Americans are chronically infected with the • 8-10,000 deaths a year are caused by HCV. Hepatitis C virus (HCV). • HCV is the leading cause for liver transplants and • 342,000 New Yorkers are estimated to be infected chronic liver disease. with HCV. • HCV deaths will increase four-fold to 38,000, by • A majority of the people infected with HCV do not the year 2010. know they have it. • Years of life lost to Hepatitis C (2001-2019) • Thousands of people go undetected each year—due 3.1 million years to inadequate risk assessment, under-screening and confusion about the use of diagnostic tests. • Cost of premature disability and death (2010-2109) $75.5 billion Hepatitis C Virus • Direct medical costs in absentee losses due to Hepatitis C $750 million/ year • HCV is a blood-borne disease transmitted by • Total medical expenditures for persons with HCV blood-to-blood contact. -

Alcoholic Liver Disease and Its Relationship with Metabolic Syndrome

Research and Reviews Alcoholic Liver Disease and Its Relationship with Metabolic Syndrome JMAJ 53(4): 236–242, 2010 Hiromasa ISHII,*1 Yoshinori HORIE,*2 Yoshiyuki YAMAGISHI,*3 Hirotoshi EBINUMA*3 Abstract Alcoholic liver disease (ALD), which occurs from chronic excessive drinking, progresses from initial alcoholic fatty liver to more advanced type such as alcoholic hepatitis, liver fibrosis, or liver cirrhosis when habitual drinking continues. In general, chance of liver cirrhosis increases after 20 years of chronic heavy drinking, but liver cirrhosis can occur in women after a shorter period of habitual drinking at a lower amount of alcohol. Alcoholic liver cirrhosis accounts for approximately 20% of all liver cirrhosis cases. The key treatment is abstinence or substantial cutting down on drinking; the prognosis is poor if the patient continues drinking after being diagnosed with liver cirrhosis. Factors that exert adverse effects on the progression of ALD include gender difference, presence of hepatitis virus, immunologic abnormality, genetic polymorphism of alcohol-metabolizing enzymes, and complication of obesity or overweight. Recently, particular attention has been paid to obesity and overweight as risk factors in the progression of ALD. Conditions such as visceral fat accumulation, obesity, and diabetes mellitus underlie the pathologic factor of metabolic syndrome (MetS). In liver, MetS may accompany fatty liver or steatohepatitis, with possible progression to liver cirrhosis in some cases. Caution is required for patients with MetS who have a high alcohol intake because alcohol consumption further accelerates the progression of liver lesions. Key words Alcoholic liver disease, Metabolic syndrome, Obesity, NAFLD/NASH Introduction following hypertension and smoking, as a global disease burden. -

Hepatitis C Virus Infection and Human Pancreatic ß-Cell Dysfunction

Pathophysiology/Complications BRIEF REPORT Hepatitis C Virus Infection and Human Pancreatic -Cell Dysfunction 1 1 MATILDE MASINI, MD SILVIA DEL GUERRA, PHD showing the characteristic insulin gran- 2 1 DANIELA CAMPANI, MD MARCO BUGLIANI, PHD ules and normally preserved mitochon- 3 1 UGO BOGGI, MD SCILLA TORRI, PHD  2 1 dria. In -cells from HCV-positive MICHELE MENICAGLI, MD STEFANO DEL PRATO, MD 1 3 pancreases, the presence of virus-like par- NICOLA FUNEL, MD FRANCO MOSCA, MD 1 4 ticles was observed, mainly close to the MARIA POLLERA, MD FRANCO FILIPPONI, MD 1 1 membranes of Golgi apparatus, which, in ROBERTO LUPI, PHD PIERO MARCHETTI, MD, PHD turn, appeared hyperplastic and dilated (Fig. 1D). The mitochondria appeared round-shaped with dispersed matrix and fragmented cristae (Fig. 1D). Additional Ϯ 2 any patients with chronic hepati- and 2 women, BMI 25.8 1.6 kg/m ) -cell changes were observed at the Ϯ tis C virus (HCV) develop type 2 and 10 HCV-negative (age 67 9 years, level of rough endoplasmic reticulum, Ϯ diabetes (1). This prevalence is 6 men and 4 women, BMI 26.8 2.0 which showed long and dilated tubular M 2 much higher than that observed in the kg/m ) donors were harvested and stud- membranes, with numerous electron- general population and in patients with ied with the approval of our local ethics dense ribosomes bound to the latter (not other chronic liver diseases such as hepa- committee. Histological studies were shown). These morphological changes titis B virus, alcoholic liver disease, and performed by immunohistochemistry were accompanied by reduced in vitro primary biliary cirrhosis. -

Vaccinations for Adults with Chronic Liver Disease Or Infection

Vaccinations for Adults with Chronic Liver Disease or Infection This table shows which vaccinations you should have to protect your health if you have chronic hepatitis B or C infection or chronic liver disease (e.g., cirrhosis). Make sure you and your healthcare provider keep your vaccinations up to date. Vaccine Do you need it? Hepatitis A Yes! Your chronic liver disease or infection puts you at risk for serious complications if you get infected with the (HepA) hepatitis A virus. If you’ve never been vaccinated against hepatitis A, you need 2 doses of this vaccine, usually spaced 6–18 months apart. Hepatitis B Yes! If you already have chronic hepatitis B infection, you won’t need hepatitis B vaccine. However, if you have (HepB) hepatitis C or other causes of chronic liver disease, you do need hepatitis B vaccine. The vaccine is given in 2 or 3 doses, depending on the brand. Ask your healthcare provider if you need screening blood tests for hepatitis B. Hib (Haemophilus Maybe. Some adults with certain high-risk conditions, for example, lack of a functioning spleen, need vaccination influenzae type b) with Hib. Talk to your healthcare provider to find out if you need this vaccine. Human Yes! You should get this vaccine if you are age 26 years or younger. Adults age 27 through 45 may also be vacci- papillomavirus nated against HPV after a discussion with their healthcare provider. The vaccine is usually given in 3 doses over a (HPV) 6-month period. Influenza Yes! You need a dose every fall (or winter) for your protection and for the protection of others around you. -

Dyspepsia in Cirrhotic Hepatitis C Patients

Journal of Rawalpindi Medical College (JRMC); 2017;21(4): 321-324 Original Article Dyspepsia in Cirrhotic Hepatitis C Patients Maryam Jalil1, Faiza Aslam 2, Talal Khurshid Bhatti 3 , Muhammad Umar 1 , Hamamatul Bushra Khaar 1 1Woman Medical Officer,THQ Hospital ,Fateh Jang;2. Research Coordinator at Research Unit, Rawalpindi Medical University; 3. Medical officer, THQ Hospital,Lalamusa. Abstract positive individuals and patients with liver cirrhosis.2 Indigestion, also known as dyspepsia, is a condition of Background:To determine the frequency of impaired digestion characterized by upper abdominal patients with dyspepsia, its patterns of presentation fullness, heartburn, nausea, belching, upper and causes along with their associations with gender abdominal pain, regurgitation, or water brash (bitter and age, amongst HCV cirrhotic patients presenting tasting liquid coming up into back of throat).3About to a tertiary care health facility of Rawalpindi. 30-40% of all adults experience symptoms of Methods: In this cross sectional study 207 HCV dyspepsia but organic cause is found in only few cases cirrhotic patients,above 25 years of age irrespective who seek medical care. The remaining cases are of gender, were included. Patients receiving labelled as having functional dyspepsia.4 Different prolonged treatment of acid suppression prior to causes of dyspepsia are gastroesophageal reflux hospitalization were excluded. After taking history disease (GERD), peptic ulcer, gastrointestinal cancers, and performing thorough physical examination, gastritis, hiatal hernia, gastroparesis, congestive routine laboratory investigations, abdominal gastropathy, cholelithiasis, food or drug intolerance ultrasonography and endoscopies were performed to and other diseases of gastrointestinal tract, liver, determine the cause of dyspepsia. pancreas and other systems.5-7 Results:Amongst 207 HCV cirrhotic patients 146 World Health Organization Statistics 2008 lists (70.5%) were presented with dyspepsia. -

Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Information for Patients

April 2021 | www.hepatitis.va.gov Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Information for Patients What is Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease? Losing more than 10% of your body weight can improve liver inflammation and scarring. Make a weight loss plan Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease or NAFLD is when fat is with your provider— and exercise to keep weight off. increased in the liver and there is not a clear cause such as excessive alcohol use. The fat deposits can cause liver damage. Exercise NAFLD is divided into two types: simple fatty liver and non- Start small, with a 5-10 minute brisk walk for example, alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Most people with NAFLD and gradually build up. Aim for 30 minutes of moderate have simple fatty liver, however 25-30% have NASH. With intensity exercise on most days of the week (150 minutes/ NASH, there is inflammation and scarring of the liver. A small week). The MOVE! Program is a free VA program to help number of people will develop significant scarring in their lose weight and keep it off. liver, called cirrhosis. Avoid Alcohol People with NAFLD often have one or more features of Minimize alcohol as much as possible. If you do drink, do metabolic syndrome: obesity, high blood pressure, low HDL not drink more than 1-2 drinks a day. Patients with cirrhosis cholesterol, insulin resistance or diabetes. of the liver should not drink alcohol at all. NAFLD increases the risk for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, Treat high blood sugar and high cholesterol and kidney disease. Ask your provider if you have high blood sugar or high Most people feel fine and have no symptoms. -

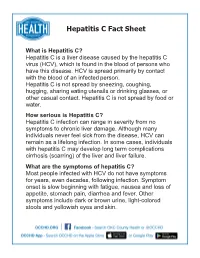

Hepatitis C Fact Sheet

Hepatitis C Fact Sheet What is Hepatitis C? Hepatitis C is a liver disease caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV), which is found in the blood of persons who have this disease. HCV is spread primarily by contact with the blood of an infected person. Hepatitis C is not spread by sneezing, coughing, hugging, sharing eating utensils or drinking glasses, or other casual contact. Hepatitis C is not spread by food or water. How serious is Hepatitis C? Hepatitis C infection can range in severity from no symptoms to chronic liver damage. Although many individuals never feel sick from the disease, HCV can remain as a lifelong infection. In some cases, individuals with hepatitis C may develop long term complications cirrhosis (scarring) of the liver and liver failure. What are the symptoms of hepatitis C? Most people infected with HCV do not have symptoms for years, even decades, following infection. Symptom onset is slow beginning with fatigue, nausea and loss of appetite, stomach pain, diarrhea and fever. Other symptoms include dark or brown urine, light-colored stools and yellowish eyes and skin. Hepatitis C Fact Sheet How is hepatitis C spread from one person to another? HCV is spread primarily by direct contact with human blood. People at increased risk for hepatitis C include: • Injecting drug users • Hemodialysis patients • Health care workers • Sexual contacts of infected persons • Persons with multiple sex partners • Recipient of transfusions before July, 1992 • Recipient of clotting factors made before 1987 What is the risk of hepatitis C transmission from an HCV infected mother to her baby? Approximately 5% of infants born to HCV infected women contract Hepatitis C. -

Hepatitis C Virus Infection December 2017

. Europe’s journal on infectious disease epidemiology, prevention and control Special edition: Hepatitis C virus infection December 2017 Featuring • Hepatitis C virus seroprevalence and prevalence of chronic infection in the adult population in Ireland: a study of residual sera, April 2014 to February 2016 • Towards elimination of hepatitis B and C in European Union and European Economic Area countries: monitoring the World Health Organization’s global health sector strategy core indicators and scaling up key interventions www.eurosurveillance.org Editorial team Editorial advisors Based at the European Centre for Albania: Alban Ylli, Tirana Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), Austria: Maria Paulke-Korinek, Vienna 171 65 Stockholm, Sweden Belgium: Koen de Schrijver; Tinne Lernout, Antwerp Telephone number Bosnia and Herzegovina: Sanjin Musa, Sarajevo +46 (0)8 58 60 11 38 Bulgaria: Iva Christova, Sofia E-mail Croatia: Sanja Music Milanovic, Zagreb [email protected] Cyprus: Maria Koliou, Nicosia Czech Republic: Jan Kynčl, Prague Editor-in-chief Denmark: Peter Henrik Andersen, Copenhagen Dr Ines Steffens Estonia: Kuulo Kutsar, Tallinn Senior editor Finland: Outi Lyytikäinen, Helsinki Kathrin Hagmaier France: Judith Benrekassa, Paris Germany: Jamela Seedat, Berlin Scientific editors Greece: Rengina Vorou, Athens Janelle Sandberg Hungary: Ágnes Hajdu, Budapest Karen Wilson Iceland: Gudrun Sigmundsdottir, Reykjavík Assistant editors Ireland: Lelia Thornton, Dublin Alina Buzdugan Italy: Paola De Castro, Rome Vilasini Roy Latvia: -

Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia in Patients with Liver and Bowel Disorders

Journal of Clinical Medicine Review Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia in Patients with Liver and Bowel Disorders Cristiana Bianco 1 , Elena Coluccio 1, Daniele Prati 1 and Luca Valenti 1,2,* 1 Department of Transfusion Medicine and Hematology, Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, 20122 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (E.C.); [email protected] (D.P.) 2 Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, Università degli Studi di Milano, 20122 Milan, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-02-50320278; Fax: +39-02-50320296 Abstract: Anemia is a common feature of liver and bowel diseases. Although the main causes of anemia in these conditions are represented by gastrointestinal bleeding and iron deficiency, autoimmune hemolytic anemia should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Due to the epidemiological association, autoimmune hemolytic anemia should particularly be suspected in patients affected by inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, such as autoimmune or acute viral hepatitis, primary biliary cholangitis, and inflammatory bowel disease. In the presence of biochemical indices of hemolysis, the direct antiglobulin test can detect the presence of warm or cold reacting antibodies, allowing for a prompt treatment. Drug-induced, immune-mediated hemolytic anemia should be ruled out. On the other hand, the choice of treatment should consider possible adverse events related to the underlying conditions. Given the adverse impact of anemia on clinical outcomes, maintaining a high clinical suspicion to reach a prompt diagnosis is the key to establishing an adequate treatment. Keywords: autoimmune hemolytic anemia; chronic liver disease; inflammatory bowel disease; Citation: Bianco, C.; Coluccio, E.; autoimmune disease; autoimmune hepatitis; primary biliary cholangitis; treatment; diagnosis Prati, D.; Valenti, L.