Geological and Geomorphological Controls on the Path of an Intermountain Roman Road: the Case of the Via Herculia, Southern Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

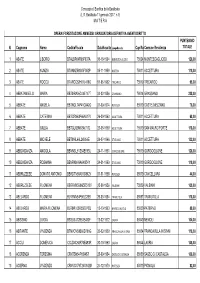

1-Graduatoria Definitiva Operai Aventi Diritto

Consorzio di Bonifica della Basilicata (L.R. Basilicata 11 gennaio 2017, n.1) M A T E R A OPERAI FORESTAZIONE AMMESSI: GRADUATORIA DEFINITIVA AVENTI DIRITTO PUNTEGGIO N. Cognome Nome CodiceFiscale DataNascita LuogoNascita Cap ResidenzaComune Residenza TOTALE 1 ABATE LIBORIO BTALBR64R06F637A 06-10-1964 MONTESCAGLIOSO 75024 MONTESCAGLIOSO 128,00 2 ABATE NUNZIA BTANNZ59S45F052P 05-11-1959 MATERA 75011 ACCETTURA 118,00 3 ABATE ROCCO BTARCC62H01L418O 01-06-1962 TRICARICO 75019 TRICARICO 98,00 4 ABBATANGELO MARIA BBTMRA56C44E147T 04-03-1956 GRASSANO 75014 GRASSANO 228,00 5 ABBATE ANGELA BBTNGL74P41G942O 01-09-1974 POTENZA 85010 CASTELMEZZANO 76,00 6 ABBATE CATERINA BBTCRN63P66A017V 26-09-1963 ACCETTURA 75011 ACCETTURA 68,00 7 ABBATE GIULIA BBTGLI69M63A017D 23-08-1969 ACCETTURA 75010 SAN MAURO FORTE 118,00 8 ABBATE MICHELE BBTMHL66L24I954E 24-07-1966 STIGLIANO 75011 ACCETTURA 132,00 9 ABBONDANZA ANGIOLA BBNNGL61S64E093U 24-11-1961 GORGOGLIONE 75010 GORGOGLIONE 128,00 10 ABBONDANZA ROSANNA BBNRNN69A64I954Y 24-01-1969 STIGLIANO 75010 GORGOGLIONE 118,00 11 ABBRUZZESE DONATO ANTONIO BBRDTN68A01G942V 01-01-1968 POTENZA 85010 CANCELLARA 44,00 12 ABBRUZZESE FILOMENA BBRFMN56M65D513V 25-08-1956 VALSINNI 75029 VALSINNI 108,00 13 ABELARDO FILOMENA BLRFMN54P66L326B 26-09-1954 TRAMUTOLA 85057 TRAMUTOLA 118,00 14 ABELARDO MARIA FILOMENA BLRMFL63R55E976Q 15-10-1963 MARSICO NUOVO 85050 PATERNO 88,00 15 ABISSINO LUIGIA BSSLGU72B53E483F 13-02-1972 LAURIA 85040 NEMOLI 104,00 16 ABITANTE VINCENZA BTNVCN59B66D766G 26-02-1959 FRANCAVILLA IN SINNI 85034 FRANCAVILLA IN SINNI 118,00 17 ACCILI DOMENICA CCLDNC60R70E483R 30-10-1960 LAURIA 85044 LAURIA 148,00 18 ACERENZA TERESINA CRNTSN54P65I457I 25-09-1954 SASSO DI CASTALDA 85050 SASSO DI CASTALDA 108,00 19 ACIERNO VINCENZO CRNVCN79T24G942M 24-12-1979 POTENZA 85010 PIGNOLA 82,00 Consorzio di Bonifica della Basilicata (L.R. -

Linea Foggia - Potenza Modifiche Circolazione Treni

DAL 14 AL 27 MAGGIO 2018 LINEA FOGGIA - POTENZA MODIFICHE CIRCOLAZIONE TRENI Da lunedì 14 a domenica 27 maggio, per lavori di potenziamento infrastrutturale nella stazione di Melfi, tutti i treni Regionali circolanti sulla tratta Foggia – Potenza potranno maturare ritardi fino a 10 minuti. Inoltre, i treni riportati nelle successive tabelle subiranno le variazioni di seguito indicate: Da POTENZA a MELFI – FOGGIA e viceversa: Treno Partenza Ora Arrivo Ora Provvedimenti R 3502 POTENZA C.le 5.28 FOGGIA 7.46 CANCELLATO DA RIONERO A FOGGIA E SOSTITUITO CON BUS nei lavorativi dal 14 al 27 maggio. NEI GIORNI FESTIVI CIRCOLA CON NUOVO NUMERO 34655 E MODIFICA L’ORARIO: Foggia p. 6.09 – R 3503 FOGGIA 5.34 POTENZA C.le 7.58 Melfi p. 07.07 – Barile p. 7.15 - Rionero A.R. p. 7.20 – Forenza p. 7.33 – Filiano p. 7.41 - Castel Lagopes. p. 7.54 – Possidente p. 7.59 – Pietragalla p. 8.05 – Avigliano p. 8.12 - Potenza M.R. p. 8.21 - Potenza Sup.re p. 8.24 – Potenza C.le a. 8.32. CANCELLATO DA FOGGIA A RIONERO E SOSTITUITO CON BUS. CIRCOLA CON IL NUOVO NUMERO R 3505 FOGGIA 6.20 POTENZA C.le 8.37 34663 CON ORIGINE CORSA DA RIONERO IN PARTENZA ALLE ORE 7.40 R 3506 POTENZA C.le 7.15 MELFI 8.46 CANCELLATO DA RIONERO A MELFI E SOSTITUITO CON BUS. CIRCOLA CON NUOVO NUMERO 34657 E MODIFICA L’ORARIO tutti i giorni dal 14 al 27 maggio: Foggia p. 9.00 – Rocchetta S.A.L. p. -

Field T Rip Guide Book

Volume N°1 - from P01 to P???30 FIELD TRIP MAP 32nd INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS A GEOLOGICAL TRANSECT ACROSS THE SOUTHERN APENNINES ALONG THE SEISMIC LINE CROP 04 - P20 INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS CONGRESS GEOLOGICAL INTERNATIONAL nd 32 Field Trip Guide Field Book Trip Leader: E. Patacca, P. Scandone Florence - Italy August 20-28, 2004 Post-Congress P20 Edited by APAT The scientific content of this guide is under the total responsibility of the Authors Edited by: APAT – Italian Agency - Via Vitaliano Brancati, 48 - 00144 Roma - Italy Editors: Luca GUERRIERI, Irene RISCHIA and Leonello SERVA English Editing: Paul MAZZA (University of Firenze), Jessica THONN Field Trip Committee: Leonello SERVA (APAT, Rome), Alessandro MICHETTI (Insubria University, Como), Giulio PAVIA (University of Torino), Raffaele PIGNONE (Regional Geological Survey of Emilia Romagna, Bologna) and Riccardo POLINO (CNR, Torino) Acknowledgments: The 32nd IGC Organizing Committee is grateful to Roberto POMPILI and Elisa BRUSTIA for their strong support….. ISBN ???? Graphic project: Full snc Firenze Back Cover: Layout and press: Tipografia Volume N°1 - from B01 to B30 32nd INTERNATIONAL GEOLOGICAL CONGRESS A GEOLOGICAL TRANSECT ACROSS THE SOUTHERN APENNINES ALONG THE SEISMIC LINE CROP 04 LEADER: E.Patacca, P. Scandone (Università di Pisa, Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra - Italy) Florence - Italy August 20-28, 2004 Post-Congress P20 A GEOLOGICAL TRANSECT ACROSS THE SOUTHERN APENNINES ALONG THE SEISMIC LINE CROP 04 P20 Leader: E. Patacca, P. Scandone Introduction section across the Southern Apennines that roughly This field trip is aimed at illustrating the major follows the line CROP 04. Figure 4, finally, is an geological features of the Apennine thrust belt- interpreted line drawing of the entire profile from foredeep-foreland system in Southern Italy from Agropoli (Tyrrhenian coast) to Barletta (Adriatic the Tyrrhenian margin of the mountain chain to the coast of the Italian Peninsula). -

Waters of Rome Journal

TIBER RIVER BRIDGES AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANCIENT CITY OF ROME Rabun Taylor [email protected] Introduction arly Rome is usually interpreted as a little ring of hilltop urban area, but also the everyday and long-term movements of E strongholds surrounding the valley that is today the Forum. populations. Much of the subsequent commentary is founded But Rome has also been, from the very beginnings, a riverside upon published research, both by myself and by others.2 community. No one doubts that the Tiber River introduced a Functionally, the bridges in Rome over the Tiber were commercial and strategic dimension to life in Rome: towns on of four types. A very few — perhaps only one permanent bridge navigable rivers, especially if they are near the river’s mouth, — were private or quasi-private, and served the purposes of enjoy obvious advantages. But access to and control of river their owners as well as the public. ThePons Agrippae, discussed traffic is only one aspect of riparian power and responsibility. below, may fall into this category; we are even told of a case in This was not just a river town; it presided over the junction of the late Republic in which a special bridge was built across the a river and a highway. Adding to its importance is the fact that Tiber in order to provide access to the Transtiberine tomb of the river was a political and military boundary between Etruria the deceased during the funeral.3 The second type (Pons Fabri- and Latium, two cultural domains, which in early times were cius, Pons Cestius, Pons Neronianus, Pons Aelius, Pons Aure- often at war. -

Stop Cava Barricelle

Val d’Agri, 15-17 October 2007 FIELDTRIP GUIDE TO ACTIVE TECTONICS STUDIES IN THE HIGH AGRY VALLEY (In the 150th anniversary of the 16 December 1857, Mw 7.0 Earthquake) Edited by Luigi Ferranti (UniNa), Laura Maschio (UniNa) and Pierfrancesco Burrato (INGV) Contributors: Francesco Bucci (UniSi), Riccardo Civico (UniRomaTre), Giuliana D’Addezio (INGV), Paolo Marco De Martini (INGV), Alessandro Giocoli (CNR-IMAA), Luigi Improta (INGV), Marina Iorio (CNR-IAMC), Daniela Pantosti (INGV), Sabatino Piscitelli (CNR-IMAA), Luisa Valoroso (UniNa), Irene Zembo (UniMi) 1 List of stops Day 1 (16 October 2007) Mainly devoted to the eastern valley shoulder A1- View point along the SP273 Paterno-Mandrano on the high Agri Valley structural and geomorphic overview of the valley A2- Barricelle quarry structural observation on a W-dipping fault zone A3- road to Marsicovetere overview of the W-dipping fault zone and observation of the Agri R. asymmetry A4- Galaino quarry deformation of slope deposits A5- Marsico Nuovo dam flat iron of the back limb of the Monte Lama-Calvelluzzo anticline A6- Camporeale discussion on converging morphologies: flat iron vs. fault scarp Day 2 (17 October 2007) Mainly devoted to the western valley shoulder B1- View point from Camporotondo on the high Agri Valley and the Monti della Maddalena range panoramic view on the “hat-like” topography of the Maddalena Mts. crest eastern branch of the MMFS and the Monte Aquila fault B2- Monticello quarry E-dipping border fault and Agri R. behaviour description of the eastern part of the ESIT700 seismic section B3- Tramutola cemetery discussion on the Tramutola mountain front: thrust vs. -

Direzione Sanitaria

SERVIZIO SANITARIO REGIONALE DI BASILICATA Azienda Sanitaria Locale di Potenza SERVIZIODIPARTIMENTO SANITARIO DI PREVENZIONEREGIONALE DI COLLETTIVA BASILICATA DELLA SALUTE UMANA – Ambito Territoriale ex ASL 1 Azienda Sanitaria Locale di PotenzaVenosa – U. O. Igiene e Sanità Pubblica – Via Della Fisica, 18 A/B - 85100 POTENZA tel. 0971/425227 fax 0971/425222 + : PRONTA REPERIBILITA’ DEL PERSONALE MEDICO E TECNICI DELLA PREVENZIONE MAGGIO 2020 AREA 1 MEDICI AREA 2 MEDICI TECN. DELLA PREVENZIONE 1 Venerdì PERNA Nicola PEPICE Giuseppe SPINIELLO Carmelo 2 Sabato PERNA Nicola PEPICE Giuseppe SPINIELLO Carmelo 3 Domenica PERNA Nicola PEPICE Giuseppe SPINIELLO Carmelo 4 Lunedì LAMBERTI Marcello PEPICE Giuseppe SPINIELLO Carmelo 5 Martedì LAMBERTI Marcello PEPICE Giuseppe SPINIELLO Carmelo 6 Mercoledì VERNOTICO Pasquale PEPICE Giuseppe SPINIELLO Carmelo 7 Giovedì VERNOTICO Pasquale PEPICE Giuseppe SPINIELLO Carmelo 8 Venerdì VERNOTICO Pasquale PEPICE Giuseppe SPINIELLO Carmelo 9 Sabato VERNOTICO Pasquale PINTO Vito SPINIELLO Carmelo 10 Domenica VERNOTICO Pasquale PINTO Vito SPINIELLO Carmelo 11 Lunedì LAMBERTI Marcello PINTO Vito RAGO Silvana 12 Martedì LAMBERTI Marcello PINTO Vito RAGO Silvana 13 Mercoledì PERNA Nicola PINTO Vito RAGO Silvana 14 Giovedì PERNA Nicola PINTO Vito RAGO Silvana 15 Venerdì PERNA Nicola PINTO Vito RAGO Silvana 16 Sabato PERNA Nicola PINTO Vito RAGO Silvana 17 Domenica PERNA Nicola PINTO Vito RAGO Silvana 18 Lunedì LAMBERTI Marcello PEPICE Giuseppe RAGO Silvana 19 Martedì LAMBERTI Marcello PEPICE Giuseppe RAGO Silvana -

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N. Purcell, 1997 Introduction The landscape of central Italy has not been intrinsically stable. The steep slopes of the mountains have been deforested–several times in many cases–with consequent erosion; frane or avalanches remove large tracts of regolith, and doubly obliterate the archaeological record. In the valley-bottoms active streams have deposited and eroded successive layers of fill, sealing and destroying the evidence of settlement in many relatively favored niches. The more extensive lowlands have also seen substantial depositions of alluvial and colluvial material; the coasts have been exposed to erosion, aggradation and occasional tectonic deformation, or–spectacularly in the Bay of Naples– alternating collapse and re-elevation (“bradyseism”) at a staggeringly rapid pace. Earthquakes everywhere have accelerated the rate of change; vulcanicity in Campania has several times transformed substantial tracts of landscape beyond recognition–and reconstruction (thus no attempt is made here to re-create the contours of any of the sometimes very different forerunners of today’s Mt. Vesuvius). To this instability must be added the effect of intensive and continuous intervention by humanity. Episodes of depopulation in the Italian peninsula have arguably been neither prolonged nor pronounced within the timespan of the map and beyond. Even so, over the centuries the settlement pattern has been more than usually mutable, which has tended to obscure or damage the archaeological record. More archaeological evidence has emerged as modern urbanization spreads; but even more has been destroyed. What is available to the historical cartographer varies in quality from area to area in surprising ways. -

University of Groningen Hellenistic Rural Settlement and the City of Thurii, the Survey Evidence (Sibaritide, Southern Italy) A

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Hellenistic Rural Settlement and the City of Thurii, the survey evidence (Sibaritide, southern Italy) Attema, Peter; Oome, Neeltje Published in: Palaeohistoria DOI: 10.21827/5beab05419ccd IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2018 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Attema, P., & Oome, N. (2018). Hellenistic Rural Settlement and the City of Thurii, the survey evidence (Sibaritide, southern Italy). Palaeohistoria, 59/60, 135-166. https://doi.org/10.21827/5beab05419ccd Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 13-11-2019 PALAEOHISTORIA ACTA ET COMMUNICATIONES INSTITUTI ARCHAEOLOGICI UNIVERSITATIS GRONINGANAE 59/60 (2017/2018) University of Groningen / Groningen Institute of Archaeology & Barkhuis Groningen 2018 Editorial staff P.A.J. -

Forenza Venosa Filiano Maschito Acerenza

"Masseria Matinella - Veltri" MADDALENA O CATACOMBE TUFARELLO TUFARELLO TUFARELLO TUFARELLO LORETO TRINITA' TRINITA' "Ex Monastero di S. Agostino" TRINITA' "Castello" "Palazzo La Torre" "Palazzo La Torre" (Area di rispetto) MANGIAGUADAGNO MATINELLE "Masseria Santangelo" (Ex Casino Santangelo) "Masseria Santangelo" (Ex Casino Santangelo) "Masseria Rotondo" (ex Villa Rotonda) "Masseria Rotondo" (ex Villa Rotonda) VENOSA "Masseria di Giustino Fortunato" "Masseria di Giustino Fortunato" PEZZA DEL CILIEGIO CASALINI SOTTANA GINESTRA ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 4 ! 4! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 4! ! ! ! 4! ! ! ! ! 4! ! MASCHITO ! ! Legenda 4! Chiesa di San Donato ! "Convento San Donato e Villa Comunale ex giardino botanico" ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! #* ! Aerogeneratori in progetto (WTG) ! ! ! ! ! 4! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 4! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! "Palazzo Nardozza" "Palazzo Colombo" 4! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 4! ! ! Aerogeneratori esistenti da dismettere ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 4! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 4 ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 4 ! ! ! !!! ! Aerogeneratori Maschito ! ! 4 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Cavidotti ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Stazione elettrica esistente ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Area vasta di studio ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! Caratteri antropici ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !4 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !4 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Centri abitati ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 4! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! -

Urban Society and Communal Independence in Twelfth-Century Southern Italy

Urban society and communal independence in Twelfth-Century Southern Italy Paul Oldfield Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of PhD. The University of Leeds The School of History September 2006 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks for the help of so many different people, without which there would simply have been no thesis. The funding of the AHRC (formerly AHRB) and the support of the School of History at the University of Leeds made this research possible in the first place. I am grateful too for the general support, and advice on reading and sources, provided by Dr. A. J. Metcalfe, Dr. P. Skinner, Professor E. Van Houts, and Donald Matthew. Thanks also to Professor J-M. Martin, of the Ecole Francoise de Rome, for his continual eagerness to offer guidance and to discuss the subject. A particularly large thanks to Mr. I. S. Moxon, of the School of History at the University of Leeds, for innumerable afternoons spent pouring over troublesome Latin, for reading drafts, and for just chatting! Last but not least, I am hugely indebted to the support, understanding and endless efforts of my supervisor Professor G. A. Loud. His knowledge and energy for the subject has been infectious, and his generosity in offering me numerous personal translations of key narrative and documentary sources (many of which are used within) allowed this research to take shape and will never be forgotten. -

Comune Di Ripacandida

REGIONE BASILICATA PROVINCIA DI POTENZA COMUNE DI RIPACANDIDA PIANO DI ASSESTAMENTO FORESTALE DEI BENI SILVO-PASTORALI Periodo di validità 2019 – 2028 RELAZIONE TECNICA Associazione temporanea di professionisti Il Capogruppo I Componenti Dottore forestale Vito Mancusi Dottore forestale Giovanni Luca Carrieri Dottore forestale Donatello P. Mininni Dottore forestale Angelo Rita 2 Sommario PREMESSA ........................................................................................................................................ 5 1. L’AMBIENTE ................................................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Inquadramento geografico ..................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Caratteristiche geologiche e geomorfologiche dell’area ....................................................... 7 1.3 Caratteri pedologici ............................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Rete idrografica ................................................................................................................... 10 1.5 Aspetti climatici .................................................................................................................. 10 1.6 Vegetazione ......................................................................................................................... 12 1.7 Aspetti faunistici................................................................................................................. -

Lista Località Disagiate - Ed

LISTA LOCALITÀ DISAGIATE Lo standard di consegna di Poste Delivery Express e Poste Delivery Box Express è maggiorato di un giorno per le spedizioni da/per le seguenti località: Regione Abruzzo Provincia L’Aquila ACCIANO COLLEBRINCIONI POGGETELLO SANTI AREMOGNA COLLELONGO POGGETELLO DI TAGLIACOZZO SANTO STEFANO SANTO STEFANO DI SANTE ATELETA COLLI DI MONTEBOVE POGGIO CANCELLI MARIE BALSORANO FAGNANO ALTO POGGIO CINOLFO SANTO STEFANO DI SESSANIO BARISCIANO FONTECCHIO POGGIO FILIPPO SCANZANO BEFFI GAGLIANO ATERNO POGGIO PICENZE SCONTRONE BUGNARA GALLO PREZZA SECINARO CALASCIO GALLO DI TAGLIACOZZO RENDINARA SORBO CAMPO DI GIOVE GORIANO SICOLI RIDOTTI SORBO DI TAGLIACOZZO CAMPOTOSTO GORIANO VALLI RIDOTTI DI BALSORANO TIONE DEGLI ABRUZZI CANSANO LUCOLI ROCCA DI CAMBIO TORNIMPARTE CAPESTRANO MASCIONI ROCCA PIA TREMONTI CAPPADOCIA META ROCCACERRO TUFO DI CARSOLI CARAPELLE CALVISIO MOLINA ATERNO ROCCAPRETURO VERRECCHIE CASTEL DEL MONTE MORINO ROCCAVIVI VILLA SAN SEBASTIANO VILLA SANTA LUCIA DEGLI CASTEL DI IERI OFENA ROSCIOLO ABRUZZI CASTELLAFIUME ORTOLANO ROSCIOLO DEI MARSI VILLA SANT’ANGELO CASTELVECCHIO CALVISIO PACENTRO SAN BENEDETTO IN PERILLIS VILLAVALLELONGA CASTELVECCHIO SUBEQUO PERO DEI SANTI SAN DEMETRIO NE’ VESTINI VILLE DI FANO Lista Località Disagiate - Ed.