Woman's Intuition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Individuation in Aldous Huxley's Brave New World and Island

Maria de Fátima de Castro Bessa Individuation in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and Island: Jungian and Post-Jungian Perspectives Faculdade de Letras Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Belo Horizonte 2007 Individuation in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and Island: Jungian and Post-Jungian Perspectives by Maria de Fátima de Castro Bessa Submitted to the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras: Estudos Literários in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Mestre em Letras: Estudos Literários. Area: Literatures in English Thesis Advisor: Prof. Julio Cesar Jeha, PhD Faculdade de Letras Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Belo Horizonte 2007 To my daughters Thaís and Raquel In memory of my father Pedro Parafita de Bessa (1923-2002) Bessa i Acknowledgements Many people have helped me in writing this work, and first and foremost I would like to thank my advisor, Julio Jeha, whose friendly support, wise advice and vast knowledge have helped me enormously throughout the process. I could not have done it without him. I would also like to thank all the professors with whom I have had the privilege of studying and who have so generously shared their experience with me. Thanks are due to my classmates and colleagues, whose comments and encouragement have been so very important. And Letícia Magalhães Munaier Teixeira, for her kindness and her competence at PosLit I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Dr. Irene Ferreira de Souza, whose encouragement and support were essential when I first started to study at Faculdade de Letras. I am also grateful to Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the research fellowship. -

'Nothing but the Truth': Genre, Gender and Knowledge in the US

‘Nothing but the Truth’: Genre, Gender and Knowledge in the US Television Crime Drama 2005-2010 Hannah Ellison Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) University of East Anglia School of Film, Television and Media Studies Submitted January 2014 ©This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that no quotation from the thesis, nor any information derived therefrom, may be published without the author's prior, written consent. 2 | Page Hannah Ellison Abstract Over the five year period 2005-2010 the crime drama became one of the most produced genres on American prime-time television and also one of the most routinely ignored academically. This particular cyclical genre influx was notable for the resurgence and reformulating of the amateur sleuth; this time remerging as the gifted police consultant, a figure capable of insights that the police could not manage. I term these new shows ‘consultant procedurals’. Consequently, the genre moved away from dealing with the ills of society and instead focused on the mystery of crime. Refocusing the genre gave rise to new issues. Questions are raised about how knowledge is gained and who has the right to it. With the individual consultant spearheading criminal investigation, without official standing, the genre is re-inflected with issues around legitimacy and power. The genre also reengages with age-old questions about the role gender plays in the performance of investigation. With the aim of answering these questions one of the jobs of this thesis is to find a way of analysing genre that accounts for both its larger cyclical, shifting nature and its simultaneously rigid construction of particular conventions. -

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

The Passing of the Mythicized Frontier Father Figure and Its Effect on The

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1991 The ap ssing of the mythicized frontier father figure and its effect on the son in Larry McMurtry's Horseman, Pass By Julie Marie Walbridge Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Walbridge, Julie Marie, "The asp sing of the mythicized frontier father figure and its effect on the son in Larry McMurtry's Horseman, Pass By" (1991). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 66. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/66 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The passing of the mythicized frontier father figure and its effect on the son in Larry McMurtry's Horseman, Pass By by Julie Marie Walbridge A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English (Literature) Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1991 ----------- ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE 7 CHAPTER TWO 1 5 CONCLUSION 38 WORKS CITED 42 WORKS CONSULTED 44 -------- -------· ------------ 1 INTRODUCTION For this thesis the term "frontier" means more than the definition of having no more than two non-Indian settlers per square mile (Turner 3). -

“Paint It Red” Written by Eoghan Mahony Directed by Dave Barrett

“Paint It Red” Written by Eoghan Mahony Directed by Dave Barrett Episode 112 #3T7812 Warner Bros. Entertainment PRODUCTION DRAFT 4000 Warner Blvd. November 17, 2008 Burbank, CA 91522 FULL BLUE 11/18/08 PINK REVS. 11/21/08 YELLOW REVS. 11/23/08 GREEN REVS. 11/24/08 © 2008 Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. This script is the property of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. No portion of this script may be performed, reproduced or used by any means, or disclosed to, quoted or published in any medium without the prior written consent of Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. THE MENTALIST “Paint It Red” Episode #112 November 24, 2008 – Green Revisions REVISED PAGES PINK REVISIONS – 11/21/08 14, 20, 21, 30, 37, 37A YELLOW REVISIONS – 11/23/08 *(ADDENDUM – SCENE 47 DIALOGUE – INSERT AT END OF SCRIPT) GREEN REVISIONS – 11/24/08 46, 47, 49, 50, 52 TEASER FADE IN: 1 EXT. A.P. CAID OIL HQ DOWNTOWN SACRAMENTO - NIGHT (N/1) 1 The SIGN outside an imposing edifice of glass and steel proclaims it to be the headquarters of A.P. CAID PETROLEUM. 2 INT. FOYER. EXECUTIVE FLOOR. A.P. CAID OIL HQ - NIGHT 2 FRANK and KEELY are locked in a fervent kiss. He’s late 30s, turned corporate suit. She’s late 20’s, in prim but sexy receptionist kit. They make their way across the luxe foyer with a slightly furtive air, stopping at a set of heavy wooden doors. KEELY Are you sure about this? What if someone sees us? FRANK Relax, baby. I’ve got it all under control. -

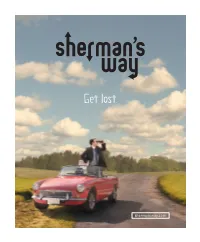

SW Press Booklet PRINT3

STARRY NIGHT ENTERTAINMENT Presents starring JAMES LE GROS (“The Last Winter” “Drugstore Cowboy”) ENRICO COLANTONI (“Just Shoot Me” “Galaxy Quest”) MICHAEL SHULMAN (“Can of Worms” “Little Man Tate”) BROOKE NEVIN (“The Comebacks” “Infestation”) with DONNA MURPHY THOMAS IAN NICHOLAS and LACEY CHABERT (“The Nanny Diaries”) (“American Pie Trilogy”) (“Mean Girls”) edited by CHRISTOPHER GAY cinematography by JOAQUIN SEDILLO written by TOM NANCE directed by CRAIG SAAVEDRA Copyright Sherman’s Way, LLC All Rights Reserved SHERMAN’S WAY Sherman’s Way starts with two strangers forced into a road trip of con - venience only to veer off the path into a quirky exploration of friendship, fatherhood and the annoying task of finding one’s place in the world – a world in which one wrong turn can change your destination. The discord begins when Sherman, (Michael Shulman) a young, uptight Ivy- Leaguer, finds himself stranded on the West Coast with an eccentric stranger and washed-up, middle-aged former athlete Palmer (James Le Gros) in an attempt to make it down to Beverly Hills in time for a career-making internship at a prestigious law firm. The two couldn't be more incompatible. Palmer is a reckless charmer with a zest for life; Sherman is an arrogant snob with a sense of entitlement. Palmer is con - tent reliving his past; Sherman is focused solely on his future. Neither is really living in the present. The only thing this odd couple seems to share is the refusal to accept responsibility for their lives. Director Craig Saavedra brings his witty sensibility into this poignant look at fatherhood and friendship that features indie stalwart James Le Gros in an unapologetic performance that manages to bring undeniable charm to an otherwise abrasive character. -

(Deb) – Katie Leclerc Currently Stars As Daphne Vasquez on The

‘CLOUDY WITH A CHANCE OF LOVE’ CAST BIOS KATIE LECLERC (Deb) – Katie Leclerc currently stars as Daphne Vasquez on the hit ABC family series “Switched At Birth.” In its third season, “Switched At Birth,” and Leclerc specifically, continue to drive a strong fan following and are respected and are applauded worldwide for their positive portrayal of deaf characters on television. Leclerc has been nominated for two Teen Choice Awards for her outstanding performance on the show. The first was in 2011 in the category of “Choice TV Break Out Star” and then again in 2013 in the category of “Summer TV Star.” Originally from Lakewood, Colorado and the youngest of three siblings, Leclerc got the acting bug when she starred in a local production of “Annie.” When the family moved to San Diego, she continued to pursue her desire to perform and began appearing in national commercials for such brands as Pepsi, Cingular, Comcast and GE. Leclerc got her big break at the age of 19 in 2004 when she was asked to guest star on “Veronica Mars,” starring Kristen Bell. She went on to have guest and recurring roles on such series as MTV’s “The Hard Times of RJ Berger,” CBS’s “CSI” and “The X List.” However, it is for portraying Raj Koothrappali’s gold-digging girlfriend Emily on the hit CBS series “The Big Bang Theory,” that brings her the most additional recognition. In film, she has starred in the Hallmark Channel Original Movie “The Confession,” as well as the independent features “The Inner Circle” and “Flying By” with Billy Ray Cyrus. -

Twelfth Night, Helena in a Midsummer Night's Dream and Yelena In

‘MARRYING FATHER CHRISTMAS’ Cast Bios ERIN KRAKOW (Miranda) – Best known for her starring role as Elizabeth Thornton in Hallmark Channel's “When Calls the Heart,” which has been renewed for a sixth season premiering in 2019, and her recurring role on Lifetime Television’s “Army Wives,” Erin Krakow has graced both the stage and screen during her acting career. Krakow is a classically trained actor and graduated with a BFA from The Juilliard School. She had starring roles in a number of the esteemed school’s productions, including Viola and Sebastian in Twelfth Night, Helena in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Yelena in Black Russian. Beyond her work at Juilliard, Krakow has appeared in many prominent stage roles, including Cecily in The Importance of Being Earnest and Shelby in the stage adaptation of Steel Magnolias. Krakow has transitioned from stage to screen, earning series regular, recurring and guest-starring roles on top television series. On Lifetime’s “Army Wives,” Krakow played the recurring role of Specialist Tanya Gabriel. She also earned the recurring role of Molly on CBS’s hit daytime soap “Guiding Light.” Krakow guest-starred on “Castle” for ABC, “NCIS: Los Angeles” and “NCIS” for CBS and “Good Girls Revolt” for Amazon/Sony. Elizabeth Thornton on “When Calls the Heart” is not Krakow’s only beloved character for Hallmark Channel. She also played lead roles Samantha in “Chance at Romance” and Christie in “A Cookie Cutter Christmas.” On Hallmark Movies & Mysteries, Krakow played Miranda in “Finding Father Christmas” and “Engaging Father Christmas,” a role she reprises in “Marrying Father Christmas.” Born in Philadelphia, Krakow grew up in South Florida where she attended Alexander W. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

The Return of the 1950S Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980S

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s Chris Steve Maltezos University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Maltezos, Chris Steve, "The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3230 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Return of the 1950s Nuclear Family in Films of the 1980s by Chris Maltezos A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities College Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Elizabeth Bell, Ph.D. Margit Grieb, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 4, 2011 Keywords: Intergenerational Relationships, Father Figure, insular sphere, mother, single-parent household Copyright © 2011, Chris Maltezos Dedication Much thanks to all my family and friends who supported me through the creative process. I appreciate your good wishes and continued love. I couldn’t have done this without any of you! Acknowledgements I’d like to first and foremost would like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. -

Put Your Foot Down

PAGE SIX-B THURSDAY, MARCH 1, 2012 THE LICKING VALLEY COURIER Elam’sElam’s FurnitureFurniture Your Feed Stop By New & Used Furniture & Appliances Specialists Frederick & May For All Your 2 Miles West Of West Liberty - Phone 743-4196 Safely and Comfortably Heat 500, 1000, to 1500 sq. Feet For Pennies Per Day! iHeater PTC Infrared Heating Systems!!! QUALITY Refrigeration Needs With A •Portable 110V FEED Line Of Frigidaire Appliances. Regular •Superior Design and Quality Price •Full Function Credit Card Sized FOR ALL Remember We Service 22.6 Cubic Feet Remote Control • All Popular Brands • Custom Feed Blends •Available in Cherry & Black Finish YOUR $ 00 $379 • Animal Health Products What We Sell! •Reduces Energy Usage by 30-50% 999 Sale •Heats Multiple Rooms • Pet Food & Supplies •Horse Tack FARM Price •1 Year Factory Warranty • Farm & Garden Supplies •Thermostst Controlled ANIMALS $319 •Cannot Start Fires • Plus Ole Yeller Dog Food Frederick & May No Glass Bulbs •Child and Pet Safe! Lyon Feed of West Liberty FINANCING AVAILABLE! (Moved To New Location Behind Save•A•Lot) Lumber Co., Inc. Williams Furniture 919 PRESTONSBURG ST. • WEST LIBERTY We Now Have A Good Selection 548 Prestonsburg St. • West Liberty, Ky. 7598 Liberty Road • West Liberty, Ky. TPAGEHE LICKING TWE LVVAELLEY COURIER THURSDAYTHURSDAY, NO, VJEMBERUNE 14, 24, 2012 2011 THE LICKING VALLEY COURIER Of Used Furniture Phone (606) 743-3405 Phone: (606) 743-2140 Call 743-3136 PAGEor 743-3162 SEVEN-B Holliday’s Stop By Your Feed Frederick & May OutdoorElam’sElam’s Power FurnitureFurniture Equipment SpecialistsYour Feed For All YourStop Refrigeration By New4191 & Hwy.Used 1000 Furniture • West & Liberty, Appliances Ky. -

Three Postmodern Detectives Teetering on the Brink of Madness

FACULTY OF EDUCATION AND BUSINESS STUDIES Department of Humanities Three Postmodern Detectives Teetering on the Brink of Madness in Paul Auster´s New York Trilogy A Comparison of the Detectives from a Postmodernist and an Autobiographical Perspective Björn Sondén 2020 Student thesis, Bachelor degree, 15 HE English(literature) Supervisor: Iulian Cananau Examiner: Marko Modiano Abstract • As the title suggests, this essay is a postmodern and autobiographical analysis of the three detectives in Paul Auster´s widely acclaimed 1987 novel The New York Trilogy. The focus of this study is centred on a comparison between the three detectives, but also on tracking when and why the detectives devolve into madness. Moreover, it links their descent into madness to the postmodern condition. In postmodernity with its’ incredulity toward Metanarratives’ lives are shaped by chance rather than by causality. In addition, the traditional reliable tools of analysis and reason widely associated with the well-known literary detectives in the era of enlightenment, such as Sherlock Holmes or Dupin, are of little use. All of this is also aggravated by an unforgiving and painful never- ending postmodern present that leaves the detectives with little chance to catch their breath, recover their balance or sanity while being overwhelmed by their disruptive postmodern objects. Consequently, the three detectives are essentially all humiliated and stripped bare of their professional and personal identities with catastrophic results. Hence, if the three detectives start out with a reasonable confidence in their own abilities, their investigations lead them with no exceptions to a point where they are unable to distinguish reality from their postmodern paranoia and madness.