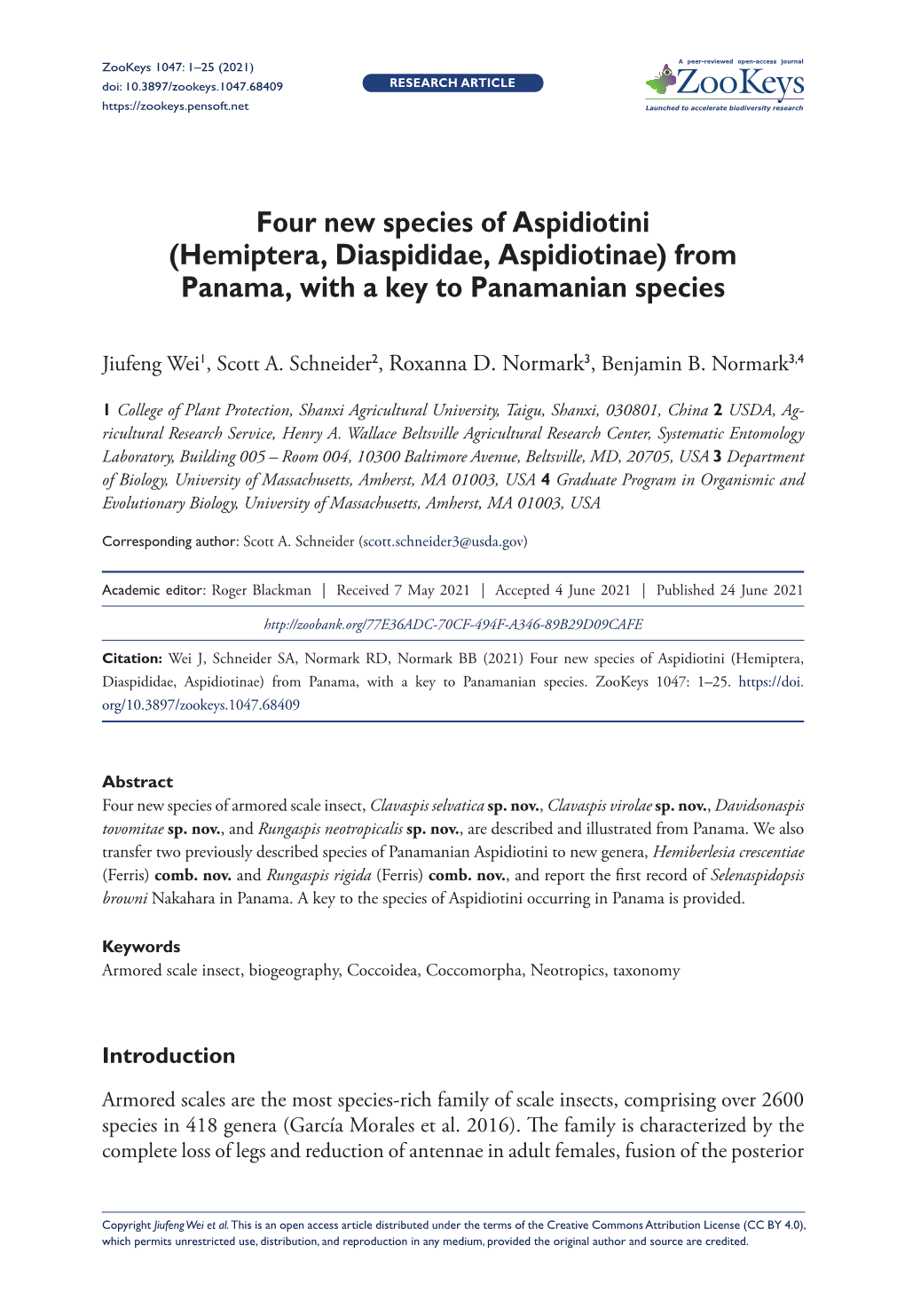

From Panama, with a Key to Panamanian Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Morphology and Adaptation of Immature Stages of Hemipteran Insects

© 2019 JETIR January 2019, Volume 6, Issue 1 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Morphology and Adaptation of Immature Stages of Hemipteran Insects Devina Seram and Yendrembam K Devi Assistant Professor, School of Agriculture, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, Punjab Introduction Insect Adaptations An adaptation is an environmental change so an insect can better fit in and have a better chance of living. Insects are modified in many ways according to their environment. Insects can have adapted legs, mouthparts, body shapes, etc. which makes them easier to survive in the environment that they live in and these adaptations also help them get away from predators and other natural enemies. Here are some adaptations in the immature stages of important families of Hemiptera. Hemiptera are hemimetabolous exopterygotes with only egg and nymphal immature stages and are divided into two sub-orders, homoptera and heteroptera. The immature stages of homopteran families include Delphacidae, Fulgoridae, Cercopidae, Cicadidae, Membracidae, Cicadellidae, Psyllidae, Aleyrodidae, Aphididae, Phylloxeridae, Coccidae, Pseudococcidae, Diaspididae and heteropteran families Notonectidae, Corixidae, Belastomatidae, Nepidae, Hydrometridae, Gerridae, Veliidae, Cimicidae, Reduviidae, Pentatomidae, Lygaeidae, Coreidae, Tingitidae, Miridae will be discussed. Homopteran families 1. Delphacidae – Eg. plant hoppers They comprise the largest family of plant hoppers and are characterized by the presence of large, flattened spurs at the apex of their hind tibiae. Eggs are deposited inside plant tissues, elliptical in shape, colourless to whitish. Nymphs are similar in appearance to adults except for size, colour, under- developed wing pads and genitalia. 2. Fulgoridae – Eg. lantern bugs They can be recognized with their antennae inserted on the sides & beneath the eyes. -

47-60 ©Österr

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Beiträge zur Entomofaunistik Jahr/Year: 2011 Band/Volume: 12 Autor(en)/Author(s): Malumphy Chris, Kahrer Andreas Artikel/Article: New data on the scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) of Vienna, including one invasive species new for Austria. 47-60 ©Österr. Ges. f. Entomofaunistik, Wien, download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Beiträge zur Entomofaunistik 12 47-60 Wien, Dezember 2011 New data on the scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) of Vienna, including one invasive species new for Austria Ch. Malumphy* & A. Kahrer** Zusammenfassung Sammeldaten von 30 im März 2008 in Wiener Parks und Palmenhäusern gesammelten Schild- und Wolllausarten (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) werden aufgelistet. Dreizehn dieser Arten (43 %) sind tropischen Ursprungs. Die San José Schildlaus (Diaspidiotus perniciosus (COMSTOCK)), die rote Austernschildlaus (Epidiaspis leperii (SIGNORET)) und die Maulbeerschildlaus (Pseudaulacaspis pentagona (TARGIONI- TOZZETTI)) (alle Diaspididae) rufen schwere Schäden an ihren Wirtspflanzen – im Freiland kultivierten Zierpflanzen hervor. Die ebenfalls nicht einheimische, invasive Art Pulvinaria floccifera (WESTWOOD) (Coccidae) wird für Österreich zum ersten Mal gemeldet. Summary Collection data are provided for 30 species of scale insects (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) found in Vienna during March 2008. Thirteen (43 %) of these species are of exotic origin. Diaspidiotus perniciosus (COMSTOCK), Epidiaspis leperii (Signoret) and Pseudaulacaspis pentagona (TARGIONI-TOZZETTI) (Diaspididae) were found causing serious damage to ornamental plants growing outdoors. The non-native, invasive Pulvinaria floccifera (WESTWOOD) (Coccidae) is recorded from Austria for the first time. Keywords: Non-native introductions, invasive species, Diaspidiotus perniciosus, Epidiaspis leperii, Pseudaulacaspis pentagona, Pulvinaria floccifera. Introduction The scale insect (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) fauna of Austria has been inadequately studied. -

Insetos Do Brasil

COSTA LIMA INSETOS DO BRASIL 2.º TOMO HEMÍPTEROS ESCOLA NACIONAL DE AGRONOMIA SÉRIE DIDÁTICA N.º 3 - 1940 INSETOS DO BRASIL 2.º TOMO HEMÍPTEROS A. DA COSTA LIMA Professor Catedrático de Entomologia Agrícola da Escola Nacional de Agronomia Ex-Chefe de Laboratório do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz INSETOS DO BRASIL 2.º TOMO CAPÍTULO XXII HEMÍPTEROS ESCOLA NACIONAL DE AGRONOMIA SÉRIE DIDÁTICA N.º 3 - 1940 CONTEUDO CAPÍTULO XXII PÁGINA Ordem HEMÍPTERA ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Superfamília SCUTELLEROIDEA ............................................................................................................ 42 Superfamília COREOIDEA ............................................................................................................................... 79 Super família LYGAEOIDEA ................................................................................................................................. 97 Superfamília THAUMASTOTHERIOIDEA ............................................................................................... 124 Superfamília ARADOIDEA ................................................................................................................................... 125 Superfamília TINGITOIDEA .................................................................................................................................... 132 Superfamília REDUVIOIDEA ........................................................................................................................... -

Zootaxa,Phylogeny and Higher Classification of the Scale Insects

Zootaxa 1668: 413–425 (2007) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2007 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Phylogeny and higher classification of the scale insects (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea)* P.J. GULLAN1 AND L.G. COOK2 1Department of Entomology, University of California, One Shields Avenue, Davis, CA 95616, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] 2School of Integrative Biology, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland 4072, Australia. Email: [email protected] *In: Zhang, Z.-Q. & Shear, W.A. (Eds) (2007) Linnaeus Tercentenary: Progress in Invertebrate Taxonomy. Zootaxa, 1668, 1–766. Table of contents Abstract . .413 Introduction . .413 A review of archaeococcoid classification and relationships . 416 A review of neococcoid classification and relationships . .420 Future directions . .421 Acknowledgements . .422 References . .422 Abstract The superfamily Coccoidea contains nearly 8000 species of plant-feeding hemipterans comprising up to 32 families divided traditionally into two informal groups, the archaeococcoids and the neococcoids. The neococcoids form a mono- phyletic group supported by both morphological and genetic data. In contrast, the monophyly of the archaeococcoids is uncertain and the higher level ranks within it have been controversial, particularly since the late Professor Jan Koteja introduced his multi-family classification for scale insects in 1974. Recent phylogenetic studies using molecular and morphological data support the recognition of up to 15 extant families of archaeococcoids, including 11 families for the former Margarodidae sensu lato, vindicating Koteja’s views. Archaeococcoids are represented better in the fossil record than neococcoids, and have an adequate record through the Tertiary and Cretaceous but almost no putative coccoid fos- sils are known from earlier. -

Data Sheets on Quarantine Pests

Prepared by CABI and EPPO for the EU under Contract 90/399003 Data Sheets on Quarantine Pests Aonidiella citrina IDENTITY Name: Aonidiella citrina (Coquillett) Synonyms: Aspidiotus citrinus Coquillett Chrysomphalus aurantii citrinus (Coquillett) Taxonomic position: Insecta: Hemiptera: Homoptera: Diaspididae Common names: Yellow scale (English) Cochenille jaune (French) Escama amarilla de los cítricos (Spanish) Notes on taxonomy and nomenclature: The original description by Coquillett is inadequate and simply refers to 'the yellow scale' on orange (Nel, 1933). A. citrina is morphologically very similar to the Californian red scale, Aonidiella aurantii (Maskell), and was considered to be a variety until Nel (1933) raised it to specific level based on a comparative study of their ecology, biology and morphology. Bayer computer code: AONDCI EU Annex designation: II/A1 HOSTS A. citrina is polyphagous attacking plant species belonging to more than 50 genera in 32 families. The main hosts of economic importance are Citrus spp., especially oranges (C. sinensis), but the insect is also recorded incidentally on a wide range of ornamentals and some fruit crops including Acacia, bananas (Musa paradisiaca), Camellia including tea (C. sinensis), Clematis, Cucurbitaceae, Eucalyptus, Euonymus, guavas (Psidium guajava), Hedera helix, Jasminum, Ficus, Ligustrum, Magnolia, mangoes (Mangifera indica), Myrica, olives (Olea europea), peaches (Prunus persica), poplars (Populus), Rosa, Schefflera actinophylla, Strelitzia reginae, Viburnum and Yucca. The main potential hosts in the EPPO region are Citrus spp. growing in the southern part of the region, around the Mediterranean. GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION A. citrina originated in Asia and has spread to various tropical and subtropical regions throughout the world. The precise distribution of A. -

Diaspididae (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) En Olivo, <I>Olea Europaea</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 2014 Diaspididae (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) en olivo, Olea europaea Linnaeus (Oleaceae), en Brasil Vera Regina dos Santos Wolff Fundação Estadual de Pesquisa Agropecuária (FEPAGRO), [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi dos Santos Wolff, Vera Regina, "Diaspididae (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) en olivo, Olea europaea Linnaeus (Oleaceae), en Brasil" (2014). Insecta Mundi. 900. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/900 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0385 Diaspididae (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) en olivo, Olea europaea Linnaeus (Oleaceae), en Brasil Vera Regina dos Santos Wolff Fundação Estadual de Pesquisa Agropecuária (FEPAGRO) Rua Gonçalves Dias 570. Porto Alegre Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil Date of Issue: September 26, 2014 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL Vera Regina dos Santos Wolff Diaspididae (Hemiptera: Coccoidea) en olivo, Olea europaea Linnaeus (Oleaceae), en Brasil Insecta Mundi 0385: 1–6 ZooBank Registered: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:8ED57F9D-E002-4269-88DA-A8DBDB41F57E Published in 2014 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. P. O. Box 141874 Gainesville, FL 32614-1874 USA http://centerforsystematicentomology.org/ Insecta Mundi is a journal primarily devoted to insect systematics, but articles can be published on any non-marine arthropod. Topics considered for publication include systematics, taxonomy, nomenclature, checklists, faunal works, and natural history. -

HOST PLANTS of SOME STERNORRHYNCHA (Phytophthires) in NETHERLANDS NEW GUINEA (Homoptera)

Pacific Insects 4 (1) : 119-120 January 31, 1962 HOST PLANTS OF SOME STERNORRHYNCHA (Phytophthires) IN NETHERLANDS NEW GUINEA (Homoptera) By R. T. Simon Thomas DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC AFFAIRS, HOLLANDIA In this paper, I list 15 hostplants of some Phytophthires of Netherlands New Guinea. Families, genera within the families and species within the genera are mentioned in alpha betical order. The genera and the specific names of the insects are printed in bold-face type, those of the plants are in italics. The locality, where the insects were found, is printed after the host plants. Then follows the date of collection and finally the name of the collector1 in parentheses. I want to acknowledge my great appreciation for the identification of the Aphididae to Mr. D. Hille Ris Lambers and of the Coccoidea to Dr. A. Reyne. Aphididae Cerataphis variabilis Hrl. Cocos nucifera Linn.: Koor, near Sorong, 26-VII-1961 (S. Th.). Longiunguis sacchari Zehntner. Andropogon sorghum Brot.: Kota Nica2 13-V-1959 (S. Th.). Toxoptera aurantii Fonsc. Citrus sp.: Kota Nica, 16-VI-1961 (S. Th.). Theobroma cacao Linn.: Kota Nica, 19-VIII-1959 (S. Th.), Amban-South, near Manokwari, 1-XII- 1960 (J. Schreurs). Toxoptera citricida Kirkaldy. Citrus sp.: Kota Nica, 16-VI-1961 (S. Th.). Schizaphis cyperi v. d. Goot, subsp, hollandiae Hille Ris Lambers (in litt.). Polytrias amaura O. K.: Hollandia, 22-V-1958 (van Leeuwen). COCCOIDEA Aleurodidae Aleurocanthus sp. Citrus sp.: Kota Nica, 16-VI-1961 (S. Th.). Asterolecaniidae Asterolecanium pustulans (Cockerell). Leucaena glauca Bth.: Kota Nica, 8-X-1960 (S. Th.). 1. My name, as collector, is mentioned thus: "S. -

Coccidology. the Study of Scale Insects (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria (E-Journal) Revista Corpoica – Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria (2008) 9(2), 55-61 RevIEW ARTICLE Coccidology. The study of scale insects (Hemiptera: Takumasa Kondo1, Penny J. Gullan2, Douglas J. Williams3 Sternorrhyncha: Coccoidea) Coccidología. El estudio de insectos ABSTRACT escama (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: A brief introduction to the science of coccidology, and a synopsis of the history, Coccoidea) advances and challenges in this field of study are discussed. The changes in coccidology since the publication of the Systema Naturae by Carolus Linnaeus 250 years ago are RESUMEN Se presenta una breve introducción a la briefly reviewed. The economic importance, the phylogenetic relationships and the ciencia de la coccidología y se discute una application of DNA barcoding to scale insect identification are also considered in the sinopsis de la historia, avances y desafíos de discussion section. este campo de estudio. Se hace una breve revisión de los cambios de la coccidología Keywords: Scale, insects, coccidae, DNA, history. desde la publicación de Systema Naturae por Carolus Linnaeus hace 250 años. También se discuten la importancia económica, las INTRODUCTION Sternorrhyncha (Gullan & Martin, 2003). relaciones filogenéticas y la aplicación de These insects are usually less than 5 mm códigos de barras del ADN en la identificación occidology is the branch of in length. Their taxonomy is based mainly de insectos escama. C entomology that deals with the study of on the microscopic cuticular features of hemipterous insects of the superfamily Palabras clave: insectos, escama, coccidae, the adult female. -

Aspidiotus Nerii Bouchè (Insecta: Hemipthera: Diaspididae)

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2003 Molecular systematics of a sexual and parthenogenetic species complex : Aspidiotus nerii Bouchè (Insecta: Hemipthera: Diaspididae). Lisa M. Provencher University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Provencher, Lisa M., "Molecular systematics of a sexual and parthenogenetic species complex : Aspidiotus nerii Bouchè (Insecta: Hemipthera: Diaspididae)." (2003). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 3090. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/3090 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOLECULAR SYSTEMATICS OF A SEXUAL AND PARTHENOGENETIC SPECIES COMPLEX: Aspidiotus nerii BOUCHE (INSECTA: HEMIPTERA: DIASPIDIDAE). A Thesis Presented by LISA M. PROVENCHER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May 2003 Entomology MOLECULAR SYSTEMATICS OF A SEXUAL AND PARTHENOGENETIC SPECIES COMPLEX: Aspidiotus nerii BOUCHE (INSECTA: HEMIPTERA: DIASPIDIDAE). A Thesis Presented by Lisa M. Provencher Roy G. V^n Driesche, Department Head Department of Entomology What is the opposite of A. nerii? iuvf y :j3MSuy ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank Edward and Mari, for their patience and understanding while I worked on this master’s thesis. And a thank you also goes to Michael Sacco for the A. nerii jokes. I would like to thank my advisor Benjamin Normark, and a special thank you to committee member Jason Cryan for all his generous guidance, assistance and time. -

Biological Responses and Control of California Red Scale Aonidiella Aurantii (Maskell) (Hemiptera: Diaspididae)

Biological responses and control of California red scale Aonidiella aurantii (Maskell) (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) by Khalid Omairy Mohammed Submitted to Murdoch University in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Science, Health, Engineering and Education Murdoch University Perth, Western Australia March 2020 Declaration The work described in this thesis was undertaken while I was an enrolled student for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Murdoch University, Western Australia. I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. To the best of my knowledge, all work performed by others, published or unpublished, has been duly acknowledged. Khalid O. Mohammed Date: March 10, 2020 I Acknowledgements بِ ْس ِمِِاللَّ ِـه َِّالر ْح َم ٰـ ِن َِّالر ِح ِيمِ ُ َويَ ْسأَلُ َونَك َِع ِن ُِّالروحِِِۖقُ ِل ُِّالر ُوح ِِم ْنِأَ ْم ِر َِر ِب َيِو َماِأ ِوتيتُ ْم ِِم َن ِْال ِع ْل ِمِإِ ََّّل َِق ِل ايًلِ﴿٨٥﴾ The research for this thesis was undertaken in the School of Veterinary and Life Science, Murdoch University. I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my supervisors Professor Yonglin Ren and Dr Manjree Agarwal “Postharvest Biosecurity and Food Safety Laboratory Murdoch” for their support with enthusiasm, constructive editing, and patience throughout the years of this wonderful project. I deeply appreciate their encouragement, assistance and for being so willing to take me on as a student. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to all those who helped me in completing this thesis. -

Biocontrol Efficacy of Entomopathogenic Fungi Against San Jose Scale Quadraspidiotus Perniciosus (Comstock) (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) in Field Trials

ISSN (Print): 0971-930X ISSN (Online): 2230-7281 Journal of Biological Control, 28(4): 214-220, 2014 JOURNAL OF Volume: 28 No. 4 (December) 2014 Research Article Biocontrol efficacy of entomopathogenic fungi against San Jose scale Quadraspidiotus perniciosus (Comstock) (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) in field trials ABDUL AHAD BUHROO* P. G. Department of Zoology, University of Kashmir, Hazratbal, Srinagar - 190006, Jammu and Kashmir, India *Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: San Jose scale Quadraspidiotus perniciosus is a key pest of apple crop in the northern states of India. The efficacy of entomopathogenic fungi - Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae sensu lato and Lecanicillium lecanii against San Jose scale was examined in three apple orchards, each located at Srinagar, Bandipora and Pulwama districts in Kashmir. The relative pathogenicity of these fungi against the pest was also evaluated during field trials. Mortality was monitored at 2-day intervals until 30 days after application. All three fungal pathogens caused mortality of the pest particularly with the increase in treatment concentration. High mortality (76-77%) was determined with B. bassiana at 15 × 105 conidia/ml. formulation followed by L. lecanii at the same formulation (mortality 73-75%) at all the experimental sites tested. M. anisopliae sensu lato was significantly less effective (mortality 47-67%) in all the three field trials. The results demonstrate the suitability of entomopathogenic fungi for controlling San Jose scale. KEY WORDS: Biological -

Reporting Service 2005, No

ORGANISATION EUROPEENNE EUROPEAN AND MEDITERRANEAN ET MEDITERRANEENNE PLANT PROTECTION POUR LA PROTECTION DES PLANTES ORGANIZATION EPPO Reporting Service Paris, 2005-05-01 Reporting Service 2005, No. 5 CONTENTS 2005/066 - First report of Tomato chlorosis crinivirus in Réunion 2005/067 - Viroids detected on tomato samples in the Netherlands 2005/068 - Recent studies on Thecaphora solani 2005/069 - Studies on Bursaphelenchus species associated with Pinus pinaster in Portugal 2005/070 - Survey on nematodes associated with Pinus trees in Spain: absence of Bursaphelenchus xylophilus 2005/071 - Studies on Bursaphelenchus species in Lithuania 2005/072 - Surveys on Bursaphelenchus xylophilus, Monilinia fructicola, Phytophthora ramorum and Pepino mosaic potexvirus in Emilia-Romagna, Italy 2005/073 - Aphelenchoides besseyi does not occur in Slovakia 2005/074 - Pests absent in Slovakia 2005/075 - Situation of several quarantine pests in Lithuania in 2004: first report of rhizomania 2005/076 - Further spread of Aulacaspis yasumatsui, a scale pest of Cycads 2005/077 - Ctenarytaina spatulata is a new psyllid pest of Eucalyptus: addition to the EPPO Alert List 2005/078 - First report of Brenneria quercina causing bark canker on oaks in Spain: addition to the EPPO Alert List 2005/079 - EPPO report on notifications of non-compliance (detection of regulated pests) 2005/080 - PQR version 4.4 has now been released 2005/081 - EPPO Conference on Phytophthora ramorum and other forest pests (Cornwall, GB, 2005-10- 05/07) 1, rue Le Nôtre Tel. : 33 1 45 20 77 94 E-mail : [email protected] 75016 Paris Fax : 33 1 42 24 89 43 Web : www.eppo.org EPPO Reporting Service 2005/066 First report of Tomato chlorosis crinivirus in Réunion In 2004/2005, pronounced leaf yellowing symptoms were observed on tomato plants growing under protected conditions on the island of Réunion.