Getting the Most out of Citizen Science for Endangered Species Such As Whale Shark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Directory of CRM Learning Destinations in the Philippines 2Nd

Directory of CRMLearningDestinations in the Philippines by League of Municipalities of the Philippines (LMP), Department of Agriculture-Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (DA-BFAR) Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project, World Wide Fund for Nature- Philippines (WWF-Philippines), and Conservation International (CI). 2ND EDITION 2009 Printed in Cebu City, Philippines Citation: LMP, FISH Project, WWF-Philippines, and CI-Philippines. 2009. Directory of CRM Learning Destinations in the Philippines. 2nd Edition. League of Municipalities of the Philippines (LMP), Department of Agriculture-Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (DA-BFAR) Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project, World Wide Fund for Nature-Philippines (WWF-Philippines), and Conservation International-Philippines (CI-Philippines). Cebu City, Philippines. This publication was made possible through support provided by the Fisheries Improved for Sustainable Harvest (FISH) Project of the Department of Agriculture-Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms and conditions of USAID Contract Nos. AID-492-C-00-96-00028- 00 and AID-492-C-00-03-00022-00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID. This publication may be reproduced or quoted in other publications as long as proper reference is made to the source. Partner coordination: Howard Cafugauan, Marlito Guidote, Blady Mancenido, and Rebecca Pestaño-Smith Contributions: Camiguin Coastal Resource Management Project: Evelyn Deguit Conservation International-Philippines: Pacifico Beldia II, Annabelle Cruz-Trinidad and Sheila Vergara Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation: Atty. Rose-Liza Eisma-Osorio FISH Project: Atty. Leoderico Avila, Jr., Kristina Dalusung, Joey Gatus, Aniceta Gulayan, Moh. -

Round Scad Exploration by Purse Seine in the South China Sea, Area III: Western Philippines

Round scad exploration by purse seine in the South China Sea, Area III: Western Philippines Item Type book_section Authors Pastoral, Prospero C.; Escobar Jr., Severino L.; Lamarca, Napoleon J. Publisher Secretariat, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center Download date 01/10/2021 13:06:13 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/40530 Proceedings of the SEAFDEC Seminar on Fishery Resources in the South China Sea, Area III: Western Philippines Round Scad Exploration by Purse Seine in the South China Sea, Area III: Western Philippines Prospero C. Pastoral1, Severino L. Escobar, Jr.1 and Napoleon J. Lamarca2 1BFAR-National Marine Fisheries Development Center, Sangley Point, Cavite City, Philippines 2BFAR-Fishing Technology Division, 860 Arcadia Bldg., Quezon Avenue, Quezon City, Philippines ABSTRACT Round scad exploration by purse seine in the waters of western Philippines was conducted from April 22 to May 7, 1998 for a period of five (5) fishing days with a total catch of 7.3 tons and an average of 1.5 tons per setting. Dominant species caught were Decapterus spp. having 70.09% of the total catch, followed by Selar spp. at 12.66% and Rastrelliger spp. 10.70%. Among the Decapterus spp. caught, D. macrosoma attained the highest total catch composition by species having 68.81% followed by D. kurroides and D.russelli with 0.31% and 1.14% respectively. The round scad fishery stock was composed mainly of juvenile fish (less than 13 cm) and Age group II (13 cm to 14 cm). Few large round scad at Age group IV and V (20 cm to 28 cm) stayed at the fishery. -

From the Bohol Sea, the Philippines

THE RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2008 RAFFLES BULLETIN OF ZOOLOGY 2008 56(2): 385–404 Date of Publication: 31 Aug.2008 © National University of Singapore NEW GENERA AND SPECIES OF EUXANTHINE CRABS (CRUSTACEA: DECAPODA: BRACHYURA: XANTHIDAE) FROM THE BOHOL SEA, THE PHILIPPINES Jose Christopher E. Mendoza Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, 14 Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543; Institute of Biology, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, 1101, Philippines Email: [email protected] Peter K. L. Ng Department of Biological Sciences, National University of Singapore, 14 Science Drive 4, Singapore 117543, Republic of Singapore Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT. – Two new genera and four new xanthid crab species belonging to the subfamily Euxanthinae Alcock (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura) are described from the Bohol Sea, central Philippines. Rizalthus, new genus, with just one species, R. anconis, new species, can be distinguished from allied genera by characters of the carapace, epistome, chelipeds, male abdomen and male fi rst gonopod. Visayax, new genus, contains two new species, V. osteodictyon and V. estampadori, and can be distinguished from similar genera using a combination of features of the carapace, epistome, thoracic sternum, male abdomen, pereiopods and male fi rst gonopod. A new species of Hepatoporus Serène, H. pumex, is also described. It is distinguished from congeners by the unique morphology of its front, carapace sculpturing, form of the subhepatic cavity and structure of the male fi rst gonopod. KEY WORDS. – Crustacea, Xanthidae, Euxanthinae, Rizalthus, Visayax, Hepatoporus, Panglao 2004, the Philippines. INTRODUCTION & Jeng, 2006; Anker et al., 2006; Dworschak, 2006; Marin & Chan, 2006; Ahyong & Ng, 2007; Anker & Dworschak, There are currently 24 genera and 83 species in the xanthid 2007; Manuel-Santos & Ng, 2007; Mendoza & Ng, 2007; crab subfamily Euxanthinae worldwide, with most occurring Ng & Castro, 2007; Ng & Manuel-Santos, 2007; Ng & in the Indo-Pacifi c (Ng & McLay, 2007; Ng et al., 2008). -

Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997

The IUCN Species Survival Commission Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997 Edited by Sarah L. Fowler, Tim M. Reed and Frances A. Dipper Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 25 IUCN The World Conservation Union Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Programme and Elasmobranch Biodiversity, Conservation and Management: Proceedings of the International Seminar and Workshop, Sabah, Malaysia, July 1997 The IUCN/Species Survival Commission is committed to communicate important species conservation information to natural resource managers, decision-makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC's Action Plans, Occasional Papers, newsletter Species and other publications are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation. To date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to SSC Specialist Groups. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and support for species conservation worldwide. The Council of Agriculture (COA), Taiwan has awarded major grants to the SSC's Wildlife Trade Programme and Conservation Communications Programme. This support has enabled SSC to continue its valuable technical advisory service to the Parties to CITES as well as to the larger global conservation community. Among other responsibilities, the COA is in charge of matters concerning the designation and management of nature reserves, conservation of wildlife and their habitats, conservation of natural landscapes, coordination of law enforcement efforts as well as promotion of conservation education, research and international cooperation. -

Aquatic Resources in the Philippines and the Extent of Poverty in the Sector

Aquatic resources in the Philippines and the extent of poverty in the sector Item Type monograph Authors Rivera, R.; Turcotte, D.; Boyd-Hagart, A.; Pangilinan, J.; Santos, R. Publisher Support to Regional Aquatic Resources Management (STREAM) Download date 04/10/2021 13:50:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/20137 Aquatic resources in the Philippines and the extent of poverty in the sector May 2002 Table of contents List of tables.......................................................................................................vi List of figures ....................................................................................................vii Abbreviations...................................................................................................viii 1 Introduction..................................................................................................1 2 Status of aquatic resources in the Philippines .........................................2 2.1 Marine resources ...............................................................................................2 2.1.1 Coral reefs .............................................................................................................. 3 2.1.2 Seagrasses and seaweeds...................................................................................... 4 2.2 Inland resources.................................................................................................5 2.2.1 Mangroves and brackish water ponds..................................................................... -

Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans Seasonal Surface Ocean

Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans 47 (2009) 114–137 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Dynamics of Atmospheres and Oceans journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dynatmoce Seasonal surface ocean circulation and dynamics in the Philippine Archipelago region during 2004–2008 Weiqing Han a,∗, Andrew M. Moore b, Julia Levin c, Bin Zhang c, Hernan G. Arango c, Enrique Curchitser c, Emanuele Di Lorenzo d, Arnold L. Gordon e, Jialin Lin f a Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, University of Colorado, UCB 311, Boulder, CO 80309, USA b Ocean Sciences Department, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA, USA c IMCS, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ, USA d EAS, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA e Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, Columbia University, Palisades, NY, USA f Department of Geography, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA article info abstract Article history: The dynamics of the seasonal surface circulation in the Philippine Available online 3 December 2008 Archipelago (117◦E–128◦E, 0◦N–14◦N) are investigated using a high- resolution configuration of the Regional Ocean Modeling System (ROMS) for the period of January 2004–March 2008. Three experi- Keywords: ments were performed to estimate the relative importance of local, Philippine Archipelago remote and tidal forcing. On the annual mean, the circulation in the Straits Sulu Sea shows inflow from the South China Sea at the Mindoro and Circulation and dynamics Balabac Straits, outflow into the Sulawesi Sea at the Sibutu Passage, Transport and cyclonic circulation in the southern basin. A strong jet with a maximum speed exceeding 100 cm s−1 forms in the northeast Sulu Sea where currents from the Mindoro and Tablas Straits converge. -

Expedition Shark #4: Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park - LAMAVE

Expedition Shark #4 Expedition Shark #4: Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park - LAMAVE Introduction Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park is one of the last refuges for sharks remaining on the planet. It provides protection to critically endangered species, serves as a sanctuary where a variety of species thrives, and redistributes life into the surrounding waters. This rare beacon of hope in Southeast Asia represents an oceanic oasis at the heart of an overexploited, overfished desert. It is a vestige of what the oceans once were, and a brilliant model for what they should be again. Despite all of this, we know very little about the sharks that call this unique UNESCO World Heritage Site home, and a research expedition is desperately needed to unlock its potential. Our team, which includes an intrepid researcher spending four months at the ranger station on this remote atoll, will conduct the first comprehensive shark survey within Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park. Our expedition will explore the secrets behind the stunning biodiversity of this reef, revealing the key to repopulating the sharks of the Coral Triangle and uncovering information that can help keep our oceans alive. Is Tubbataha home to Asia's most productive tiger shark nurseries? Where do the whale sharks that frequent this reef travel, and are they venturing into the dangerous waters of the South China Sea to reproduce? This expedition represents an unprecedented effort to understand these animals so we can work for their protection. Join us now and be a part of the solution. Photo ©Simon Pierce | MMF 1 Expedition Shark #4: Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park - LAMAVE What is Expedition Shark #4? On May 22nd 2018, a team of the world's top shark scientists will travel to Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park to conduct a groundbreaking assessment of sharks and rays within the park during a 12-day expedition. -

GUIDE to PHILIPPINE RETREAT VENUES for Your Next Retreat

Discover the Perfect Venue GUIDE TO PHILIPPINE RETREAT VENUES For Your Next Retreat RETREATS AND VENUES INDEX INDEX Contents 02 - 03 04 - 05 06 07 08 - 09 10 - 11 12 - 22 23 RETREAT AND VENUES Choose from a 1000+ venues vetted by www.retreatsandvenues.com our community of over 750 retreat leaders. 2 | © RETREATSANDVENUES © RETREATSANDVENUES | 3 ABOUT US ABOUT US Discover Your Perfect RETREATS Choose from a 1000+ venues & VENUES vetted by Retreat Venues our community of over 750 retreat leaders. FIND A VENUE e help retreat leaders find their perfect venue for free. Browse our Then our retreat venue experts will curate a custom list of venues that match website or book a discovery call today for a more personalized your retreat vision. We then work 1 on 1 with you to help you book or hold Wtouch. We will start by learning more about your retreat vision on your perfect venue. a discovery call (15 to 30 minutes). 4 | © RETREATSANDVENUES © RETREATSANDVENUES | 5 PHILIPPINES LIQUID DIVE DUMAGUETE Liquid Dive Dumaguete 34 PEOPLE 14 ROOMS MNL RESORT NEGROS ORIENTAL, LEARN MORE PHILIPPINES We are small boutique dive resort based on the beach front in Dauin. 14 beach cottages, 2 swimming pools, 5* CDC dive center, massage cabana, bar/restaurant & large second floor chill area which can Discover Your be used for yoga and other activities. Next Retreat Venue Many outdoor activities in the area including biking, trekking, running trails, canyoning and PHILIPPINES of course diving and snorkeling which is our main focus. Discover leading retreats, stunning venues and welcoming hosts around the world 6 | © RETREATSANDVENUES © RETREATSANDVENUES | 7 ANISIAM - PRIVATE RETREAT ANISIAM - PRIVATE RETREAT Anisiam - Private Retreat ACTIVITIES LEARN MORE MNL 6 ROOMS 12 PEOPLE • Beach • Scuba Diving • Biking • Snorkeling BATANGAS,PHILIPPINES VILLA • Hiking • Island Hopping A small private resort caters to one private group at a time. -

Spratly Islands

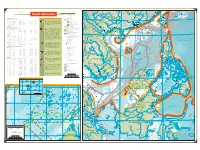

R i 120 110 u T4-Y5 o Ganzhou Fuqing n h Chenzhou g Haitan S T2- J o Dao Daojiang g T3 S i a n Putian a i a n X g i Chi-lung- Chuxiong g n J 21 T6 D Kunming a i Xingyi Chang’an o Licheng Xiuyu Sha Lung shih O J a T n Guilin T O N pa Longyan T7 Keelung n Qinglanshan H Na N Lecheng T8 T1 - S A an A p Quanzhou 22 T'ao-yüan Taipei M an T22 I L Ji S H Zhongshu a * h South China Sea ng Hechi Lo-tung Yonaguni- I MIYAKO-RETTO S K Hsin-chu- m c Yuxi Shaoguan i jima S A T21 a I n shih Suao l ) Zhangzhou Xiamen c e T20 n r g e Liuzhou Babu s a n U T Taichung e a Quemoy p i Meizhou n i Y o J YAEYAMA-RETTO a h J t n J i Taiwan C L Yingcheng K China a a Sui'an ( o i 23 n g u H U h g n g Fuxing T'ai- a s e i n Strait Claimed Straight Baselines Kaiyuan H ia Hua-lien Y - Claims in the Paracel and Spratly Islands Bose J Mai-Liao chung-shih i Q J R i Maritime Lines u i g T9 Y h e n e o s ia o Dongshan CHINA u g B D s Tropic of Cancer J Hon n Qingyuan Tropic of Cancer Established maritime boundary ian J Chaozhou Makung n Declaration of the People’s Republic of China on the Baseline of the Territorial Sea, May 15, 1996 g i Pingnan Heyuan PESCADORES Taiwan a Xicheng an Wuzhou 21 25° 25.8' 00" N 119° 56.3' 00" E 31 21° 27.7' 00" N 112° 21.5' 00" E 41 18° 14.6' 00" N 109° 07.6' 00" E While Bandar Seri Begawan has not articulated claims to reefs in the South g Jieyang Chaozhou 24 T19 N BRUNEI Claim line Kaihua T10- Hsi-yü-p’ing Chia-i 22 24° 58.6' 00" N 119° 28.7' 00" E 32 19° 58.5' 00" N 111° 16.4' 00" E 42 18° 19.3' 00" N 108° 57.1' 00" E China Sea (SCS), since 1985 the Sultanate has claimed a continental shelf Xinjing Guiping Xu Shantou T11 Yü Luxu n Jiang T12 23 24° 09.7' 00" N 118° 14.2' 00" E 33 19° 53.0' 00" N 111° 12.8' 00" E 43 18° 30.2' 00" N 108° 41.3' 00" E X Puning T13 that extends beyond these features to a hypothetical median with Vietnam. -

Bohol Denizinin Gizemli Incisi

Trakya Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 697 Aralık 2020 Cilt 22 Sayı 2 (697-716) DOI: 10.26468/trakyasobed.765678 Araştırma Makalesi/Research Article BOHOL DENİZİNİN GİZEMLİ İNCİSİ: PANGLAO ADASI1 MYSTERIOUS PEARL OF THE BOHOL SEA: THE PANGLAO ISLAND Emin ATASOY* Geliş Tarihi:07.07.2020 Kabul Tarihi:04.11.2020 (Received) (Accepted) ÖZ: Bohol eyaletinin bir parçası olan Panglao adası Visayas Adalar Grubu’nda yer alan küçük ama yoğun nüfuslu bir adadır. Bohol denizinin sularıyla çevrili olan ada 91,1 km2’lik alana ve 82 000 kişilik nüfusa sahiptir. Düz ovalar, alçak kıyılar, az eğimli düzlükler, mangrov ormanları ve tepelik araziler Panglao adasının en önemli doğal unsurlarını oluşturmaktadırlar. Adanın kıyılarında çok sayıda koy, plaj, atol, falez, burun, mercan ve magrov ormanı yer almaktadır. Bu araştırmada Panglao adasının coğrafi konumu, genel coğrafi özellikleri açıklandığı gibi adanın başlıca turizm unsurları da kısaca ele alınmıştır. Adanın başlıca fiziki ve beşeri özellikleri irdelenerek adanın turizm potansiyeli resmedilmeye çalışılmıştır. Ayrıca adanın doğu ve batı kıyılarında yer alan başlıca konaklama tesisleri, plajları ve otelleri tespit edilmeye çalışılmıştır. Çalışmanın sonuç kısmında, Panglao adasının en önemli turizm avantajları irdelenmiştir. Anahtar Kelimeler: Filipinler Cumhuriyeti, Turizm, Panglao Adası, Bohol Eyaleti ABSTRACT: The Panglao Island, which is a part of the Bohol province, is a small but densely populated island within the Visayas Islands Group. The island surrounded by the water of the Bohol Sea, the island has an area of 91.1 square kilometers and a population of 82,000 people. Flat plains, low coasts, low slope plains, mangrove forests and hilly lands constitute the most important natural elements of the Panglao Island. -

TRNP Comprehensive Tourism Management Plan 1| Page

Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park and World Heritage Site Comprehensive Tourism Management Plan 2013 HOTO: YVETTE LEE YVETTE HOTO: P 12/9/2013 Tubbataha Protected Area Management Boar Tubbataha Management Office Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 BACKGROUND……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………4 TOURISM IN THE TRNP……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...6 Legal and Management Framework ............................................................................................... 8 UNESCO ................................................................................................................................. 10 Ramsar................................................................................................................................... 10 TRNP Tourism Benefits................................................................................................................ 10 TRNP Tourism Products............................................................................................................... 11 SCUBA Diving.......................................................................................................................... 11 Liveaboard dive operations ..................................................................................................... 14 Non-diving and other tourism activities.................................................................................... 15 TRNP Visitor’s Profile ................................................................................................................. -

(Emydocephalus Annulatus) in the Bohol Sea, Philippines

SEAVR 2019: 035‐036 ISSN: 2424‐8525 Date of publication: 26 February 2019 Hosted online by ecologyasia.com New locality records of the Turtle‐headed Seasnake (Emydocephalus annulatus) in the Bohol Sea, Philippines Abner A. BUCOL [email protected] Observer: Abner A. Bucol. Photograph by: Abner A. Bucol. Subject identified by: Abner A. Bucol. Location: Bitaug, Enrique Villanueva, Siquijor, Philippines (9.302555°N, 123.608498°E) Depth: 2‐3 metres. Habitat: coral reef crest with extensive macroalgae (Sargassum sp.). Date and time: 05 May 2015, 15:30 hrs. Identity of subject: Turtle‐headed Seasnake, Emydocephalus annulatus (Reptilia: Serpentes: Elapidae). Description of record: While conducting a fish survey on the coral reef of Bitaug, Enrique Villanueva, Siquijor a single Turtle‐headed Seasnake Emydocephalus annulatus was observed and photographed (Fig. 1). The seasnake rested for about 10 minutes, after which it started foraging the coral reef bottom. In addition to this record, the species is now documented from other locations (see Site Summary below). Fig. 1. Emydocephalus annulatus from Bitaug, Enrique Villanueva, Siquijor. © Abner A. Bucol 35 Site Summary: Based on the author’s records, and images from other unpublished sources (mainly from underwater surveys made by staff of Silliman University Angelo King Center for Research and Environmental Management [SUAKCREM] ), Emydocephalus annulatus is now known from the following sites : 1) Snake Reef near Pamilacan Island, Bohol (see Alcala et al., 2000) 2) Banilad, Mangnao Oct 14,