Case Report Management of Total Transection of Nasoendotracheal Tube During Lefort I Osteotomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CST-On-Demand-Binder.Pdf

Zander Perioperative Education Zander CST Exam Preparation Course Zander Perioperative Education Certification Preparation for CNOR, CAPA-CPAN, CST and CBSPD Wendy Zander MSN/Ed, RN, CNOR [email protected] Test Taking Strategies Objectives: 1. Apply Test Taking Strategies for the CST exam 2. Create a Personal Study Plan 3. Eligibility • Registering for the exam • Exam Format • Time Management • Test Taking Strategies Eligibility • Current or previously Certified Surgical Technologist (CST) ▫ Evidence of CST Certification • Graduate of a surgical technology program accredited by CAAHEP ▫ Evidence of proof of graduation • Graduate of a surgical technology accredited by ABHES ▫ Evidence of proof of graduation www.periop-ed.com 1 Zander Perioperative Education Military Eligible • A graduate of a military training program in surgical technology is always eligible whether it was before, during or after having CAAHEP accreditation. ▫ a copy of your DD214 (must state location of the base where program was completed), ▫ a copy of your graduation certificate from the surgical technology training program ▫ a smart transcript Accelerated Alternate Delivery (AAD) Pathway • Have on-the-job training in surgical technology • Are a graduate from a surgical technology program that did not hold CAAHEP accreditation during your enrollment CST Testing Fees First Time Test Takers Exam Fee (AST Members) Exam Fee (Non Members) $190 $290 Current or Previous Certified Surgical Technologist Renewing First Time Test Takers Certification by Examination Exam Fee -

Minimal Endoscope-Assisted Thyroidectomy Through a Retroauricular Approach: an Evolving Solo Surgery Technique

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Minimal Endoscope-assisted Thyroidectomy Through a Retroauricular Approach: An Evolving Solo Surgery Technique Myung Jin Ban, MD,*w Jae Won Chang, MD,z Won Shik Kim, MD,y Hyung Kwon Byeon, MD, PhD,y Yoon Woo Koh, MD, PhD,y and Jae Hong Park, MD, PhD* (RA), or transoral approach.1–5 Endoscopic thyroidectomy Abstract: This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility and efficacy of through an RA approach is an especially excellent choice minimal endoscope-assisted thyroidectomy (MEAT) through a for head and neck surgeons because of their familiarity with retroauricular (RA) approach. Most of the thyroidectomy oper- the direction of the approach, the short distance to the ative time was accounted for by direct visualization through the thyroid gland, and a good cosmetic outcome without the RA window, minimizing interference between surgical instruments. 6 Endoscope use was minimized and limited to critical surgical need for additional incisions. aspects, including preservation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve and Despite the advantages of the RA approach, funda- parathyroid glands. The recurrent laryngeal nerve was neuro- mental limitations of endoscopic surgery still exist, includ- monitored throughout the procedure. MEAT through an RA ing a narrow operative field that restricts the free movement approach was performed in 8 patients with papillary thyroid car- of instruments. Gas insufflation, an additional incision for cinoma (mean tumor size, 1.2 ± 0.5 cm). The mean patient age was the endoscope port, robotic arm assistance, and a flexible 41.1 ± 7.5 years. The endoscopic operating time was endoscope holder for solo surgery have all been used to 19 ± 3.4 minutes, and no postoperative hematoma, seroma, or overcome this limitation.3,7,8 vocal cord paralysis was observed. -

Rapid HTA Report Ultrasonic Energy Devices for Surgery July 2014

Rapid HTA report 1 Ultrasonic energy devices for surgery July 2014 1 This report should be cited as: Migliore A, Corio M, Perrini MR, Rivoiro C, Jefferson T. Ultrasonic energy devices for surgery: rapid HTA report. Agenas, Agenzia nazionale per i servizi sanitari regionali. Rome, July 2014. Contributions Authors Antonio Migliore, Mirella Corio, Maria Rosaria Perrini, Chiara Rivoiro, and Tom Jefferson Agenas, Agenzia nazionale per i servizi sanitari regionali, Area Funzionale Innovazione, Sperimentazione e Sviluppo, via Puglie 23, 00187 Rome (Italy) Corresponding author Antonio Migliore, MSc ([email protected]) Clinical experts Mario Alessiani, MD FACS Division of General Surgery, Varzi Hospital, University of Pavia (Italy) Marco Filauro, MD Division of General and Hepatobiliopancreatic Surgery, Galliera Hospital, Genova (Italy) Invited reviewers Chuong Ho, MD MSc Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), Ottawa (Canada) Björn Fahlgren, MSc 2 Comité d’évaluation des technologies de santé (CEDIT), Paris (France) Acknowledgements Authors would like to thank Marina Cerbo (Agenas) and Simona Paone (Agenas), for the valuable help in reviewing the research protocol and the first draft of the report, Patrizia Brigoni (Agenas) for performing the systematic literature searches, Fabio Bernardini (Agenas) for his relevant support in retrieving the publications, and Laura Velardi (Agenas) for supporting consultation and analysis of databases. Declaration on the conflict of interest and privacy Authors, Clinical expert and External Reviewers declare that they do not receive benefits or harms from the publication of this report. None of the authors have or have held shares, consultancies or personal relationships with any of the producers of the devices assessed in this document. -

Thoracoscopic Spine Surgery for Decompression and Stabilization of the Anterolateral Thoracolumbar Spine

Neurosurg Focus 19 (6):E4, 2005 Thoracoscopic spine surgery for decompression and stabilization of the anterolateral thoracolumbar spine AMIN AMINI, M.D., M.SC., RUDOLF BEISSE, M.D., AND MEIC H. SCHMIDT, M.D. Department of Neurosurgery, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah; and Department of Trauma Surgery, Berufsgenossenschaftliche Unfallklinik Murnau, Germany The anterior thoracolumbar spine can be exposed via a variety of approaches. Historically, open anterolateral or pos- terolateral approaches have been used to gain access to the anterior thoracolumbar spinal column. Although the expo- sure is excellent, open approaches are associated with significant pain and respiratory problems, substantial blood loss, poor cosmesis, and prolonged hospitalization. With the increasing use of the endoscope in surgical procedures and recent advances in video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, minimally invasive thoracoscopic spine surgery has been developed to decrease the morbidity associated with open thoracotomy. The purpose of this article is to illustrate the surgical technique of a minimally invasive thoracoscopic approach to the anterolateral thoracolumbar spine and to dis- cuss its potential indications and contraindications in patients with diseases involving the anterior thoracic and lumbar regions. KEY WORDS • endoscopic spinal surgery • thoracoscopy • thoracic spine • lumbar spine • thoracoscopic spinal instrumentation Since the introduction of thoracoscopic surgery by Jaco- Minimal access surgical techniques can potentially de- baeus15 in 1910, the technique has undergone enormous crease spinal access morbidity and speed recovery and advances. With the development of high-quality video im- healing.4,7,16,17 At the University of Utah Medical Center, we aging, small endoscopes, and modified new instruments, have performed 30 thoracoscopic spine surgeries for tho- video-assisted thoracic surgery has become the minimally racolumbar trauma, tumors, and infection. -

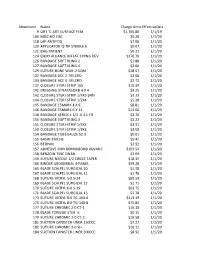

Mnemonic Name Charge Amounteffectivedate 9 ORT TJ ART

Mnemonic Name Charge AmountEffectiveDate 9 ORT TJ ART SURFACE FEM $1,765.80 1/1/19 100 MISC NO CHG $0.20 1/1/20 118 LAP ANTIFOG $7.06 1/1/20 120 APPLICATOR Q-TIP STERILE 6 $0.07 1/1/20 121 BAG PATIENT $0.21 1/1/20 124 ENDO ALLIANCE INFLAT SYRNG DEV $176.70 1/1/20 126 BANDAGE SOFT KLING 2 $1.88 1/1/20 127 BANDAGE SOFT KLING 4 $2.60 1/1/20 129 SUTURE BONE WAX 2.5QM $28.57 1/1/20 132 BANDAGE ACE 2 VELCRO $2.06 1/1/20 133 BANDAGE ACE 3 VELCRO $2.72 1/1/20 137 CLOSURE STERI-STRIP 1X5 $10.39 1/1/20 141 DRESSING STRATASORB 4 X 4 $9.25 1/1/20 142 CLOSURE STERI-STRIP 1/4X3 BRN $3.33 1/1/20 144 CLOSURE STERI-STRIP 1/2X4 $5.28 1/1/20 145 BANDAGE ESMARK 4 X 9 $8.81 1/1/20 146 BANDAGE ESMARK 6 X 12 $13.00 1/1/20 148 BANDAGE KERLIX 4 1/2 X 4.1 YD $3.70 1/1/20 150 BANDAGE SOFT KLING 3 $2.23 1/1/20 151 CLOSURE STERI-STRIP 1/4X3 $3.31 1/1/20 153 CLOSURE STERI-STRIP 1/8X3 $3.00 1/1/20 154 BANDAGE TUBEGAUZE SZ 3 $0.01 1/1/20 155 BASIN EMESIS $0.41 1/1/20 156 BEDPAN $2.92 1/1/20 157 ADHESIVE SKIN DERMABOND ADVANC $103.54 1/1/20 158 BENZOIN TINC SWAB $2.09 1/1/20 159 SUTURE NEEDLE 1/2 CIRCLE TAPER $18.35 1/1/20 160 BINDER ABDOMINAL 4-PANEL $59.28 1/1/20 165 BLADE SCALPEL SURGICAL 10 $1.78 1/1/20 167 BLADE SCALPEL SURGICAL 11 $1.78 1/1/20 168 SUTURE VICRYL 5-0 S-24 $69.59 1/1/20 169 BLADE SCALPEL SURGICAL 12 $1.71 1/1/20 170 SUTURE VICRYL 6-0 S-29 $63.75 1/1/20 171 BLADE SCALPEL SURGICAL 15 $1.78 1/1/20 173 SUTURE VICRYL 8-0 TG-160-6 $113.19 1/1/20 175 SUTURE VICRYL 8-0 TG-140-8 $75.84 1/1/20 177 SUTURE CHROMIC 2-0 CT-1 $16.10 1/1/20 178 BLADE TONGUE STER. -

Comparison of Ultrasonic Device Versus Bipolar Diathermy Tonsillectomy in Children Mukesh Kumar Sah,1 Yogesh Neupane,2 Rajendra Prasad Sharma Guragain,2

J Nepal Health Res Counc 2019 Jan-Mar;17(42): 71-5 Original Article DOI https://doi.org/10.33314/jnhrc.1751 Comparison of Ultrasonic Device Versus Bipolar Diathermy Tonsillectomy in Children Mukesh Kumar Sah,1 Yogesh Neupane,2 Rajendra Prasad Sharma Guragain,2 1Department of ENT- Head and Neck surgery, National medical college, Birgunj, Nepal, 2Department of ENT- Head and Neck surgery, Institute of medicine, Kathmandu, Nepal. ABSTRACT Background: Intraoperative bleeding and postoperative pain are two commonest concerns for both patient and surgeon in tonsillectomy. This study was aimed to compare intraoperative blood loss and early postoperative pain between ultrasonic device and bipolar diathermy tonsillectomy in children. Methods: Prospective, interventional, single blinded, comparative study was carried out from September 2016 to September 2017 including children up to age 15 years who underwent tonsillectomy either by bipolar diathermy or ultrasonic device. Intraoperative blood loss was recorded using standard sized gauge technique. Post-tonsillectomy pain on first five postoperative days (early postoperative pain) was assessed using Visual analog scale for children older than 5 years and FLACC score for children up to 5 years respectively.Means were compared. Results: 38 children (76 tonsils) were included in the study out of which 31 were boys (62 tonsils) and 7 were girls (14 tonsils). The mean intraoperative blood loss in ultrasonic dissection group was 13.94 ml and 13.91 ml in bipolar diathermy group. This difference was not statistically significant (p=0.974). Post-operative pain on 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th days were significantly less (p<0.05) in ultrasonic device group compared to bipolar diathermy group. -

Supplies Over Seas Order Form Anesthesia Blood Pressure Cuffs

Supplies Over Seas Order Form This order form is to be used as a guide to select needed medical dry supplies and equipment for your shipment. Because we rely on donations of supplies from our Hospital Recycling Partners, exact quantities may not be available at certain times. For dry supplies, shipments will include pallets of the dry supply categories (blue bar on attached chart) and may include boxes of other items in the category. Anesthesia Quantity Item Quantity Item Adapters & Connectors Endotracheal Tube Cuffed (Adult) Airway: Nasopharyngeal - Adult Endotracheal Tube Cuffed (Pediatric) Airway: Nasopharyngeal - Pediatric Endotracheal Tube Uncuffed (Adult) Airway: Oral - Adult Endotracheal Tube Uncuffed (Pediatric) Airway: Oral - Pediatric Endotracheal Tube Holder Anesthesia Face Mask - Adult Epidural Needle Anesthesia Face Mask - Pediatric Esophageal Stethoscope Anesthesia Extension Set Eye Cover Anesthesia Gas Sampling Line Filter Needle Anesthesia Pump Set Head Support Arterial Line Supplies Hyperinflation System Bite Block/Guard Intubating Stylet Anesthesia Tray: Block, Epidural, Spinal, etc. Laryngeal Mask - Adullt Breathing Bag Laryngeal Mask - Pediatric Breathing Circuit Pediatric/Infant/Neonate Manifold Breathing Circuit Adult PEEP Valve Broncho-Cath Pressure Infusor CO2 Detector Pressure Tubing Corrugated Tubing Spinal Needle Ventilator Circuit Blood Pressure Cuffs Specify fitting for your equipment (1-tube vs. 2-tube, type of fitting): Quantity Item Quantity Item BP Cuff - Neonatal 1 BP Cuff - Pediatric BP Cuff - Neonatal -

Repair Services

Repair Services Flexible Endoscopes o Video, Fiber, Small Diameter Rigid/Semi-Rigid Endoscopes o Small Diameter, Offset Operating, Specialty Power Orthopedic Handpieces o Battery, Electric, Specialty Shavers, Attachments o Dental Handpieces Surgical Cameras o HD, Control Units, Couplers o Printers Fiber Optic Light Cords/Cables o Head Lights, Microscopes, Lasers o New Light Cords Harmonic Scalpels Transducers / Probes o Urological, Abdominal, Laparoscopic, TEE Patient Monitoring, Cables, Ultra Sound o Finger Probes, Fetal Transducers, TOCOs, Dopplers o Philips monitoring equipment, MMS… Manual Instruments o Refurbish, Repair, Sharpen o Custom Manufacturing, Tray Service Ophthalmic Instruments o Phaco Handpieces, Diamond Knives o Cryo Probes, Vitrectomy & Fragmentation Handpieces Foot Pedals Battery Packs Loaners and Advanced Exchange Options Available (800) 843-8730 v151005 www.asurg.com Flexible Endoscope Repair Our certified repair facility provides complete service for your flexible endoscopes to meet the original specifications for the following manufacturers, Olympus, Pentax, Fujinon, Stryker, Wolf, Welch Allyn, ACMI, and Karl Storz. Advanced Surgical’s unique and exclusive approach to flexible endoscope repair allows healthcare providers to extend the life of their valuable equipment while dramatically reducing their respective maintenance and repair budgets. Historically, Advanced Surgical provides the lowest maintenance cost by procedure in the industry. We specialize in small diameter flexible endoscopes, including Bronchoscopes, -

Ultrasonic Osteotomy in Oral Surgery and Implantology ORAL AND

Vol. 108 No. 3 September 2009 ORAL AND MAXILLOFACIAL IMPLANTS Ultrasonic osteotomy in oral surgery and implantology Alberto González-García, DDS,a Márcio Diniz-Freitas, DDS, PhD,a Manuel Somoza-Martín, DDS, PhD,a and Abel García-García, MD, PhD,b Santiago de Compostela, Spain UNIVERSITY OF SANTIAGO DE COMPOSTELA Over the past decade, coinciding with the appearance of a number of new ultrasonic surgical devices, there has been a marked increase in interest in the use of ultrasound in oral surgery and implantology. This paper reviews the published literature on ultrasonic osteotomy in this context, summarizes its advantages and disadvantages, and suggests when it may and may not be the technique of choice. (Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009;108:360-367) The use of ultrasound for medical diagnosis was first This review is based on a search of the main on-line investigated in the 1940s and 1950s and became well medical databases for papers on ultrasonic bone surgery established in the 1960s. The possibility of surgical published in major oral surgery, periodontal and dental applications was also explored in the 1940s,1 but wide implant journals between January 1960 and August clinical use in Western nations was for a long period 2008, using the keywords “piezoelectric,” “ultrasonic,” limited to dental practice, where it continues to be used “bone,” and “surgery.” Other relevant papers were for supra- and infragingival dental cleaning, and root identified in the references sections of papers retrieved scaling,2-4 for apical box preparation prior to regro- by the primary search. -

A REVOLUTIONARY APPROACH in PERIODONTAL SURGERIES Swyeta Jain Gupta1,Vivek Gautam2,Amit Gupta3 1.Senior Lecturer,Department of Periodontics and Implantology,I.T.S

International Journal of Dental and Health Sciences Review Article Volume 02,Issue 05 PIEZOSURGERY – A REVOLUTIONARY APPROACH IN PERIODONTAL SURGERIES Swyeta Jain Gupta1,Vivek Gautam2,Amit Gupta3 1.Senior Lecturer,Department of Periodontics and Implantology,I.T.S. Centre for Dental Studies and Research,Ghaziabad 2.MDS,Prosthodontics (Private Practitioner), Gautam Multispeciality Dental Clinic,P.N Plaza Complex,Below Bank Of India,Sigra,Varanasi,Uttar Pradesh ,India. 3.Senior Lecturer, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology and Microbiology,I.T.S. Dental College, Hospital and Research Centre,Greater Noida ABSTRACT: Piezoelectric surgery, also known as piezosurgery, is an osseous surgical technique first described by Vercellotti (2004) utilizing an innovative ultrasonic surgical apparatus, known as the Mectron piezosurgery device. Piezoelectric device is an innovative tool developed as an alternative to the mechanical and electrical instruments that are used in conventional oral surgical procedures. Because of its highly selective and accurate nature, with its cutting effect exclusively targeting hard tissue, its use may be extended to more complex oral surgical procedures, as well as to other interdisciplinary problems. It can be used for selective cutting of bone depending on bone mineralization, without damaging the adjacent soft tissue (e.g. vessels, nerves or mucosa), providing a clear visibility in the operating field, and cutting with sensitivity without the generation of heat. Hence, user must be knowledgable and trained enough to adapt their operating technique in order to utilize the advantages of piezosurgery. This review summarizes on the clinical importance of piezosurgery pertaining to its use in periodontal sugeries. Piezosurgery ensures the 3 ‘P’s that is predictability, less post operative pain and increased patient’s compliance in various disciples of dentistry. -

The Tether™ – Vertebral Body Tethering System Is a Non-Fusion the Tether Spinal Device Intended for Treatment of Idiopathic Scoliosis

INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE en DEVICE DESCRIPTION ™ The Tether™ – Vertebral Body Tethering System is a non-fusion The Tether spinal device intended for treatment of idiopathic scoliosis. Vertebral Body Tethering System Anchors and vertebral body screws are placed laterally from a thoracoscopic or thoracotomy approach into the vertebral body on the convex side of a spinal deformity. A SULENE® polyethylene terephthalate (PET) tensioning cord is secured to the vertebral Zimmer Biomet Spine, Inc. only 10225 Westmoor Dr. body screws with set screws to connect the levels of the construct. Westminster, CO 80021 USA The device provides a lateral tension band across the convex +1 800.447.3625 zimmerbiomet.com side of the spine that, on insertion and tensioning, partially corrects the curvature, and subsequently can arrest or correct the deformity through modulation of remaining spinal growth. In addition, the subject system includes instrumentation for insertion, Humanitarian Device. Authorized by Federal law for use in manipulation, and removal of the implants. the treatment of skeletally immature patients that require MATERIALS surgical treatment to obtain and maintain correction of The Tether™ - Vertebral Body Tethering System is manufactured progressive idiopathic scoliosis, with a major Cobb angle of from: • Anchors: Ti 6Al-4V ELI titanium alloy per ASTM F136 30 to 65 degrees whose osseous structure is dimensionally • Set Screws: Ti 6Al-4V ELI titanium alloy per ASTM F136 adequate to accommodate screw fixation, as determined by • Bone Screws: Ti 6Al-7Nb titanium alloy per ISO 5832-11 radiographic imaging. Patients should have failed bracing with an hydroxyapatite coating per ISO 13779-2 and/or be intolerant to brace wear. -

Einarsson-Myomectomy-Article.Pdf

During laparoscopic myomectomy, extract the fibroid by applying generous traction with the tenaculum and counter-traction with an atraumatic grasper and ultrasonic shears. Once you have entered the correct surgical plane, grasp the fibroid near the hysterotomy and simply roll it out of the uterus. 48 OBG Management | March 2010 | Vol. 22 No. 3 SURGICAL TECHNIQUES Laparoscopic myomectomy: 8 Pearls From preoperative imaging to postoperative analgesia, the choices you make determine the ease of the procedure and the quality of the outcome yomectomy is the surgery of choice for women Jon I. Einarsson, who have symptomatic fibroids and who wish to MD, MPH retain their uterus. And laparoscopic myomecto- Dr. Einarsson is Assistant Professor M of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and my is preferable to the abdominal approach in many ways, Reproductive Biology at Harvard offering:1-4 IN THIS Medical School and Chief of the ARTICLE Division of Minimally Invasive • faster recovery Gynecology at Brigham and • a shorter hospital stay When and how to Women’s Hospital in Boston. • diminished blood loss treat uterine fibroids The author reports no financial • decreased adhesion formation page 50 relationships relevant to this article. • a comparable or higher rate of pregnancy. Nevertheless, laparoscopic myomectomy is a techni- How MRI can guide cally challenging procedure with surgeon-specific limita- treatment: 3 cases tions. The biggest challenge: appropriately suturing the page 53 hysterotomy site. In this article, I share my experience with laparoscopic myomectomy and offer 8 pearls that may contribute to a Should you worry successful outcome. about uterine rupture in postmyomectomy pregnancy? Don’t settle on page 58 1.laparoscopy prematurely Given its advantages over the abdominal route, laparoscop- Watch the author ic myomectomy should be the preferred approach in the remove a fibroid at treatment of symptomatic uterine fibroids FIGURE( 1, page obgmanagement.com 50).