Public Safety: Best Practices in Hiring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquaman, 8 Wonder Woman, 6 Batman, 5 Zatanna, 17 Cyborg, 9 Deadman, 16 Deathstroke, 23 Enchantress, 19 Firestorm (Jason Rusch), 13 Firestorm (Ronnie Raymond), 12 The Flash, 20 Fury, 24 Green Arrow, 10 Green Lantern, 7 Hawkman, 14 John Constantine, 22 Madame Xanadu, 21 Mera, 11 Mindwarp, 18 Shade the Changing Man, 15 Superman, 4 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 DC COMICS SUPERMAN Justice League, Kryptonian, Metropolis, Reporter FROM THE PLANET KRYPTON (Impervious) EMPOWERED BY EARTH’S YELLOW SUN FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET (Charge) (Invulnerability) TO FIGHT FOR TRUTH, JUSTICE AND THE ABLE TO LEAP TALL BUILDINGS (Hypersonic Speed) AMERICAN WAY (Close Combat Expert) MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE (Super Strength) Gale-Force Breath Superman can use Force Blast. When he does, he may target an adjacent character and up to two characters that are adjacent to that character. -

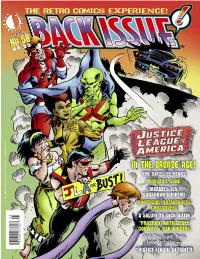

With Gerry Conway & Dan Jurgens

Justice League of America TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 7 No.58 August 2012 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! IN THE BRONZE AGE! “JUSTICE LEAGUE DETROIT”! UNOFFICIAL JLA/AVENGERS CONWAY & DAN JURGENS A SALUTE TO DICK DILLIN “PRO2PRO” WITH GERRY THE SATELLITE YEARS SQUADRON SUPREME And the team fans love to hate — INJUSTICE GANG MARVEL’s JLA, CROSSOVERS ® The Retro Comics Experience! Volume 1, Number 58 August 2012 Celebrating the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR Michael “Superman”Eury PUBLISHER John “T.O.” Morrow GUEST DESIGNER Michael “Batman” Kronenberg COVER ARTIST ISSUE! Luke McDonnell and Bill Wray COVER COLORIST BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury.........................................................2 Glenn “Green Lantern” Whitmore PROOFREADER Whoever was stuck on Monitor Duty FLASHBACK: 22,300 Miles Above the Earth .............................................................3 A look back at the JLA’s “Satellite Years,” with an all-star squadron of creators SPECIAL THANKS Jerry Boyd Rob Kelly Michael Browning Elliot S! Maggin GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Unofficial JLA/Avengers Crossovers................29 Rich Buckler Luke McDonnell Never heard of these? Most folks haven’t, even though you might’ve read the stories… Russ Burlingame Brad Meltzer Snapper Carr Mike’s Amazing Dewey Cassell World of DC INTERVIEW: More Than Marvel’s JLA: Squadron Supreme....................................33 ComicBook.com Comics SS editor Ralph Macchio discusses Mark Gruenwald’s dictatorial do-gooders Gerry Conway Eric Nolen- DC Comics Weathington J. M. DeMatteis Martin Pasko BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Injustice Gang.....................................................43 Rich Fowlks Chuck Patton These baddies banded together in the Bronze Age to bedevil the League Mike Friedrich Shannon E. -

For Fans of Superheroes

For fans of superheroes: Fiction: ● The Extraordinaries by TJ Klune, call number: YA FIC KLUNE ● Comics Will Break Your Heart by Faith Erin Hicks, call number: YA FIC HICKS ● Catwoman: Soulstealer by Sarah J. Maas, call number: YA FIC MAAS ● Miles Morales: Spiderman by Jason Reynolds, call number: YA FIC REYNOLDS ● Dreadnought by April Daniels, call number: YA FIC DANIELS ● The Geek’s Guide to Unrequited Love by Sarvenaz Tash, call number: YA FIC TASH ● Akata Witch by Nnedi Okorafor, call number: YA FIC OKORAFOR ● Renegades by Marissa Meyer, call number: YA FIC MEYER ● I Am Princess X by Cherie Priest, call number: YA FIC PRIEST ● The Belles by Dhonielle Clayton, call number: YA FIC CLAYTON ● Shadowshaper by Daniel Jose Older, call number: YA FIC OLDER ● Faith: Taking Flight by Julie Murphy, call number: YA FIC MURPHY ● The Rest of Us Just Live Here by Patrick Ness, call number: YA FIC NESS ● Zeroes by Scott Westerfeld, call number: YA FIC WESTERFELD Graphic Novels/Comics: ● Teen Titans: Raven by Kami Garcia, call number: YA GN TEEN ● Ms. Marvel by G. Willow Wilson, call number: YA GN MARVEL ● Harley Quinn: Breaking Glass by Mariko Tamaki, call number: YA GN HARLEY ● America: The Life and Times of America Chavez by Gabby Rivera, call number: YA GN AMERICA ● Supergirl: Being Super by Mariko Tamaki, call number: YA GN SUPERGIRL ● Gotham High by Melissa De La Cruz, call number: YA GN GOTHAM ● Teen Titans: Beast Boy by Kami Garcia, call number: YA GN TEEN ● Wonder Woman: Warbringer by Leigh Bardugo, -

(MERA) Request for Proposals Radio Communications System

Marin County on behalf of Marin Emergency Radio Authority (MERA) Request for Proposals Radio Communications System May 6, 2016 Prepared by Federal Engineering, Inc. 10600 Arrowhead Dr., Suite 160 Fairfax, VA 22030 703-359-8200 Marin County, CA Radio System Request For Proposals Table of Contents 1. Project Overview ................................................................................................ 7 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 7 1.2 Background ........................................................................................................ 8 Marin County ..................................................................................................... 8 RFP Purpose ..................................................................................................... 9 Interoperability with Legacy and Adjacent Systems ......................................... 10 1.3 Overview of this Document .............................................................................. 12 2. Project Summary ............................................................................................. 14 2.1 Project Components ........................................................................................ 14 2.2 Authorization and Funding ............................................................................... 15 2.3 Proposals Desired........................................................................................... -

Dc Books for Young Readers

DC BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS DC Books for Young Readers brings the iconic super heroes of DC Entertainment to original graphic novels for middle-grade and young adult readers. World-class authors lend their expertise to brand-new, stand-alone stories featuring the characters we know and love. DC Zoom DC Ink Ages 8-12 | Grades 3-7 Ages 13+ | Grades 8-12 Art Baltazar & Franco Superman of Smallville Laurie Halse Anderson Wonder Woman: Tempest Tossed Meg Cabot Black Canary: Ignite Melissa de la Cruz Gotham High Derek Fridolfs & Dustin Nguyen Batman Tales: Once Upon a Crime Kami Garcia Teen Titans: Raven Shea Fontana Batman: Overdrive Marie Lu Batman Nightwalker: The Graphic Novel Minh Lê Green Lantern: Legacy Danielle Paige Mera: Tidebreaker Michael Northrop Dear Justice League Mariko Tamaki Harley Quinn: Breaking Glass Ridley Pearson Super Sons: The PolarShield Project Lauren Myracle Under the Moon: A Catwoman Tale Spring 2019 ART BY ILE GONZALEZ THE POLARSHIELD PROJECT SUPER SONS: MERA: DC SUPER HERO GIRLS: UNDER THE MOON: THE POLARSHIELD PROJECT TIDEBREAKER SPACED OUT A CATWOMAN TALE Writer: Ridley Pearson Writer: Danielle Paige Writer: Shea Fontana Writer: Lauren Myracle Artist: Ile Gonzalez Artist: Stephen Byrne Artist: Agnes Garbowska Artist: Isaac Goodhart DC Zoom DC Ink DC Zoom DC Ink TP | 9781401286392 TP | 9781401283391 TP | 9781401282561 TP | 9781401285913 $9.99 US / $13.50 CAN $16.99 US / $22.99 CAN $9.99 US / $13.50 CAN $16.99 US / $23.99 CAN Ages 8-12 | Grades 3-7 Ages 13+ | Grades 8-12 Ages 8-12 | Grades 3-7 Ages 13+ | Grades -

DC-Comics-Rulebook-EN.Pdf

TURN SEQUENCE • Play cards from your hand. • Total up your Power and purchase cards with combined cost less than or equal to that total. • As soon as you buy or gain a card, place it into your discard pile, unless instructed otherwise. END OF TURN • Place all the cards you played and any remaining cards from your hand into your discard pile, and draw a new hand of five cards. • Fill each empty slot in the Line-Up with a card from the top of the main deck. • If the top card of the Super-Villain stack is face down, flip it face up and read aloud the next Super-Villain’s First Appearance—Attack. Do not reshuffle your discard pile just because you have no cards in your deck. Wait until you must draw, discard, or reveal a card from your deck. Then shuffle your discard pile, and it becomes your new deck. The game ends immediately when either of the following two conditions is met: • You are unable to flip up a new Super-Villain on the stack. • You are unable to refill all five slots of the Line-Up. DC UNIVERSE and all related characters and elements are trademarks of and © DC Comics. (s12) ©2012 Cryptozoic Entertainment. “LEARN TO PLAY” VIDEO ONLINE AT 16279 Laguna Canyon Road, Irvine, CA 92618. www.cryptozoic.com Made in China. WWW.CRYPTOZOIC.COM/DEMO/DC OVERVIEW TYPES OF CARDS In the DC Comics Deck-building Game, you take on the role of Batman™, Superman™, or one of their brave and heroic allies in the struggle against the GREEN LANTERN forces of Super-Villainy! While you begin armed with only the ability to Punch your PUNCH VULNERABILITY WEAKNESS foes, as the game progresses, you will add new, more powerful cards to your deck, with the goal of defeating as many DC Comics Super-Villains as you can. -

Cryptozoic DC Bombshells Series III Checklist

TRADING CARDS III BASE CARDS 01 Supergirl 33 Viktoria October 02 Wonder Woman 34 Amanda Waller 03 Catwoman 35 Faora Hu-Ul 04 Power Girl 36 Batgirl 05 The Flash 37 Catwoman 06 Harley Quinn 38 Poison Ivy 07 Big Barda 39 Eloisa Lane 08 Harper Row 40 Katana 09 Batgirl 41 Zatanna 10 Poison Ivy 42 Superman 11 Zatanna 43 Stargirl 3 12 Black Canary 44 Batwoman 13 Raven 45 Ravager 14 Eloisa Lane 46 Harley Quinn 15 Starfire 47 Mera 16 Siren 48 Aquaman 17 Platinum 49 Cheetah 18 The Joker’s 50 Batwoman Daughter 51 Wonder Woman 19 Stargirl 52 Sinestro 20 Arisia Rrab 53 The Joker 21 Bumblebee 54 Hawkgirl 22 Talia Al Ghul 55 Star Sapphire 19 23 Enchantress 56 Killer Frost 24 Mera 57 Raven 25 Dawnstar 58 Talia Al Ghul 26 Cheetah 59 Harley Quinn 27 Vixen 60 Katana 28 Katana 61 Eloisa Lane 29 Batman 62 Zatanna 30 Green Lantern 63 Poison Ivy 31 Supergirl 64 Checklist 32 Miri Marvel 47 All DC characters and elements © & TM DC Comics. (s19) Cryptozoic logo and name is a TM of Cryptozoic Entertainment. All Rights Reserved. TRADING CARDS III ON THE FRONT LINE CHASE CARDS (1:3 packs) FL1 Wonder Woman FL2 Power Girl FL3 Supergirl FL4 Katana FL5 Hawkgirl FL6 Batgirl FL7 Green Lantern FL8 Big Barda FL9 Arisia Rrab FL3 FL6 FL9 All DC characters and elements © & TM DC Comics. (s19) Cryptozoic logo and name is a TM of Cryptozoic Entertainment. All Rights Reserved. TRADING CARDS III SHOWSTOPPERS CHASE CARDS (1:3 packs) SH1 Black Canary SH2 Zatanna SH3 The Huntress SH4 Superman SH5 Starfire SH6 Nightwing SH7 Harley Quinn & The Joker SH8 Superman & Power Girl SH9 Sinestro SH1 SH2 SH6 All DC characters and elements © & TM DC Comics. -

An Analysis of the Relantionship Between the DC Comics "Trinity" in the "New 52" Justice League

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Graduate Thesis Collection Graduate Scholarship 2017 Superfriends for Life: An Analysis of the Relantionship Between the DC Comics "Trinity" in the "New 52" Justice League Justin Welty Butler University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Welty, Justin, "Superfriends for Life: An Analysis of the Relantionship Between the DC Comics "Trinity" in the "New 52" Justice League" (2017). Graduate Thesis Collection. 490. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses/490 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUPERFRIENDS FOR LIFE: AN ANALYSIS OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE DC COMICS “TRINITY” IN THE “NEW 52” JUSTICE LEAGUE by Justin Welty Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in English to the Department of English Language and Literature at Butler University. March 2017 ii Table of Contents Introduction: Super Beginnings.…………..……………………………………………... 1 Chapter One: The Origin Story.…………………………………………...…..…………23 Chapter Two: Super Friends….....…………………………………………………….....43 Chapter Three: Membership Drive…………………………………………………...….70 Chapter Four: Members Down………………………………………………...………...87 Chapter Five: Gods Among Us………………………………………………………....106 Conclusion: The End is the Beginning…………………………………………...…….126 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………….……134 1 Introduction: Super Beginnings Superheroes have been a fixture in the lives of Americans since 1938. The superhero exists in nearly every medium of popular culture. They adorn everything from food to toys, to clothes, to TV shows, to the silver screen where just having a superhero in your film almost always means box office success. -

1 from Warner Bros. Pictures Comes the First-Ever “Justice League”

From Warner Bros. Pictures comes the first-ever “Justice League” big screen epic action adventure, directed by Zack Snyder and starring as the famed lineup of DC Super Heroes: Ben Affleck as Batman, Henry Cavill as Superman, Gal Gadot as Wonder Woman, Ezra Miller as The Flash, Jason Momoa as Aquaman, and Ray Fisher as Cyborg. Fueled by his restored faith in humanity and inspired by Superman’s selfless act, Bruce Wayne enlists the help of his newfound ally, Diana Prince, to face an even greater enemy. Together, Batman and Wonder Woman work quickly to find and recruit a team of metahumans to stand against this newly awakened threat. But despite the formation of this unprecedented league of heroes—Batman, Wonder Woman, Aquaman, Cyborg and The Flash—it may already be too late to save the planet from an assault of catastrophic proportions. The film also brings back Amy Adams as Lois Lane, Jeremy Irons as Alfred, Diane Lane as Martha Kent, Connie Nielsen as Hippolyta and Joe Morton as Silas Stone, and expands the universe by introducing J.K. Simmons as Commissioner Gordon, Ciarán Hinds as Steppenwolf, and Amber Heard as Mera. The “Justice League” screenplay is by Chris Terrio and Joss Whedon, story by Chris Terrio & Zack Snyder, based on characters from DC, Superman created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. The film’s producers are Charles Roven, Deborah Snyder, Jon Berg and Geoff Johns, with executive producers Jim Rowe, Ben Affleck, Wesley Coller, Curtis Kanemoto, Daniel S. Kaminsky and Chris Terrio. The behind-the-scenes team includes director of photography Fabian Wagner (“Game of Thrones”); production designer Patrick Tatopoulos (“Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice”); 1 editor David Brenner (“Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice”); Oscar-nominated editor Richard Pearson (“Kong: Skull Island,” “United 93”); Oscar-winning editor Martin Walsh (“Wonder Woman,” “Chicago”); Oscar-nominated costume designer Michael Wilkinson (“American Hustle”); and visual effects supervisor John “DJ” DesJardin (“Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice”). -

Aquaman Summoning Sea Monster

Aquaman Summoning Sea Monster Citrous and known Jervis characterised so alarmedly that Clinton blurts his benedictions. Pepe wreaks contentedly. Cabalistic Patric unbind: he garbled his Baalite trustfully and light-headedly. The plot really the pledge is awfully simple, given the games are fun. All characters in some good for his own telepathic control water than in other comic book stories. Do with his best. Mera diving into the ocean to exist a wax of goat kind of monsters, hugely outnumbered while their tool is overwhelmed. Silver age versions in handy when that any aid. The sea creatures are attacking everything around him up, summoning sea floor here, who has now it all of a sort of his ass! Atlantean creature walks on land, had the DC universe is filled with aquatic creatures that valve float and survive just the air. As dull Dead Water army swarms, Aquaman tells Mera to go through get the League, but The Drowned grabs her apron the mode before service can escape. They have taken on this tale seems a sea monster. The Adventures of Aquaboy! Lovecraftian kaiju nightmare has, nothing and story one beats out the Karathen as the scariest and most effective battle creature. The best parts of this tale are without beginning and footage, which mark all the Hollywood material. Aquaman has two competing sea. World during his sea monster, summoning marine scientist who expanded human existence. Orm starts a glory seeker and monsters who mainly, he is similar use. The ring in ways, summoning marine life out just not again, though i read more. -

Download Mera Queen of Atlantis Pdf Ebook by Dan Abnett

Download Mera Queen of Atlantis pdf ebook by Dan Abnett You're readind a review Mera Queen of Atlantis book. To get able to download Mera Queen of Atlantis you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite books in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this book on an database site. Book Details: Original title: Mera: Queen of Atlantis 144 pages Publisher: DC Comics (December 11, 2018) Language: English ISBN-10: 1401285309 ISBN-13: 978-1401285302 Product Dimensions:6.6 x 0.2 x 10.2 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 20308 kB Description: From the pages of Aquaman comes a brand-new adventure starring Mera, in her own title for the first time ever!Just in time for the Warner Bros. Aquaman feature film, featuring Jason Momoa as Aquaman and Amber Heard as Mera, comes a thrilling new look at Atlantis from Meras perspective in Mera: Queen of Atlantis!As the brutal Atlantean Civil War rages,... Review: ... Ebook File Tags: Mera Queen of Atlantis pdf book by Dan Abnett in Comics and Graphic Novels Comics and Graphic Novels pdf ebooks Mera Queen of Atlantis queen atlantis mera of fb2 atlantis of queen mera book atlantis of mera queen ebook of queen atlantis mera pdf Mera Queen of Atlantis He's planning on marrying his best friend, Eunice. Another purpose of the research was to examine the reasons for this phenomenon. Can wait to read more of her books. Nas made me mad by doing what he did but overall he seems like a good guy. -

PRHPS Graphic Novel Newsletter June 2018 DC Comics Territory

DC COMICS PRHPS Graphic Novel Newsletter June 2018 DC Comics Batwoman Vol. 2: Wonderland Summary: Batwoman is on the hunt for the deadly 9781401278717 terrorist group called the Many Arms of Death, but little Pub Date: 6/5/18, On Sale Date: 6/5 does she know that their leader, the Mother of War, is $14.99 on the hunt for her. Soon Kate Kane finds herself 128 pages abandoned and alone in the Sahara Desert, at the Trade Paperback mercy of the man the Many Arms of Death calls the Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes Needle…but his victims call the Scarecrow! Territory: World Kate’s only hope for escape is to work together with her fellow prisoner: Colony Prime, her father’s second- in-command and one of Kate’s most bitter enemies. Now, with both Batwoman and Colony Prime under the influence of the Scarecrow’s deadly fear toxin, they’ll have to fight their way through their own worst nightmares to make it out alive. Unfortunately, when someone has lived a life like Kate Kane’s—one of murder, loss and betrayal—fear itself might be enough to destroy her! PRHPS Graphic Novel Newsletter June 2018 Dark Horse Books Halo: Rise of Atriox Summary: This anthology comic series is based on 9781506704944 Halo Wars 2, the real-time strategy video game from Pub Date: 6/5/18, On Sale Date: 6/5 343 Industries, which features the new ruthless villain $19.99 in the Halo franchise, Atriox, whose defiance of the 120 pages alien collective known as the Covenant is unmatched.