Breaking the Silence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

安全理事会 Distr.: General 25 February 2015 Chinese Original: English

联合国 S/2015/138 安全理事会 Distr.: General 25 February 2015 Chinese Original: English 2015 年 2 月 25 日秘书长给安全理事会主席的信 谨随函转递禁止化学武器组织(禁化武组织)总干事根据安全理事会第 2118(2013)号决议第 12 段提交的第十七次月度报告(见附件)。该报告所述期间为 2015 年 1 月 23 日至 2 月 22 日。 我欣慰地注意到,叙利亚阿拉伯共和国境内剩余的 12 个化学武器生产设施 的销毁工作正在继续,第一个和第二个地下结构的销毁现已得到禁止化学武器组 织核实。 关于阿拉伯叙利亚共和国的初次申报和随后的修正,禁化武组织技术专家正 在继续与叙利亚当局进行对话。自我上次写信(S/2015/56)以来,禁化武组织申报 评估小组对阿拉伯叙利亚共和国进行了访问,以便与叙利亚当局举行进一步协 商,并继续开展技术层面的讨论。如我此前所强调的那样,叙利亚当局与禁化武 组织之间的持续合作对于解决这方面的悬而未决的问题仍然至关重要。 阁下知道,2015 年 2 月 4 日我收到禁化武组织总干事转递了执行理事会所作 决定的文函,决定涉及正在调查关于有毒化学品在阿拉伯叙利亚共和国境内被用 作武器指控的实况调查团的报告。我于 2015 年 2 月 6 日写信(S/2015/95),向安全 理事会主席转递了这一文函。在该项决定中,执行理事会除其他外注意到总干事 表示,他将把实况调查团的报告连同执行理事会内对调查团工作的讨论情况包括 在其每月提交安全理事会的报告中。因此,谨附上迄今发布的实况调查团的三份 报告(见附件,附录二至四)。关于执行理事会的相关讨论情况见总干事定期的每 月报告。 实况调查团的工作正在继续进行。我一如既往地借此机会重申,我坚决谴责 冲突的任何一方将有毒化学品当作武器加以使用的行为。 请紧急提请安全理事会成员注意本信及其附件为荷。 潘基文(签名) 15-02871 (C) 020315 020315 *1502871* S/2015/138 附件 谨递交我题为“消除叙利亚化学武器方案一事的进展”的报告,供转递安全 理事会。我的报告是根据禁止化学武器组织执行理事会第 EC-M-33/DEC.1 号决 定的有关规定和联合国安全理事会第 2118(2013)号决议(2013 年 9 月 27 日)而拟写 的,报告期为 2015 年 1 月 23 日至 2015 年 2 月 22 日,其中还按照执行理事会第 EC-M-34/DEC.1 号决定(2013 年 11 月 15 日)的要求作了汇报。另外还随函附上了 负责查明有关氯在阿拉伯叙利亚共和国被用作武器的指称的事实真相的事实调 查组的三份报告。 阿赫迈特·尤祖姆居(签名) 2/119 15-02871 (C) S/2015/138 附录一 禁止化学武器组织总干事的说明 消除叙利亚化学武器方案一事的进展 1. 根据执行理事会(下称“执理会”)第三十三次会议的决定(EC-M-33/DEC.1, 2013 年 9 月 27 日)第 2(f)分段,技术秘书处(下称“技秘处”)应每个月向执理会 报告该决定的执行情况。根据联合国安全理事会第 2118(2013)号决议第 12 段, 技秘处的报告还将通过秘书长向安全理事会提交。本文为第 17 份此种月度报告。 2. 执理会第三十四次会议通过了题为“叙利亚化学武器和叙利亚化学武器生产 设施的具体销毁要求”的决定(EC-M-34/DEC.1,2013 年 11 月 15 日)。在该决定 第 22 段中,执理会决定技秘处应“在按执理会 EC-M-33/DEC.1 号决定第 2(f)分 段的规定提出报告的同时”,报告决定的执行情况。 3. 执理会第四十八次会议还通过了题为“禁化武组织派往叙利亚的事实调查组 的报告”的决定(EC-M-48/DEC.1,2015 年 2 月 4 日)。 4. -

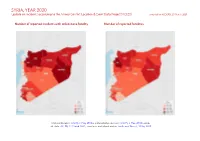

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 6187 930 2751 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 2 Battles 2465 1111 4206 Strategic developments 1517 2 2 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 1389 760 997 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 449 2 4 Riots 55 4 15 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 12062 2809 7975 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

L:>Rs(Olf/Vof

ORGANISATION FOR THE PROHIBITION OF CHEMICAL WEAPONS Dirutor-Ctntral OPCW The lf<lgue, 18 December 2014 ?014 OEC 2 3 Johan de \V ittl.>"n 31 1./()!)(Jill)5480/14 I q--- II 8 J--i 2517 JR The Ha)!U< !:....... ...��4._�·; i/� ..,.. !.: t l t•l;_ �� Tht' Nethnbnds o:F 'i llc ;,t.Q.l;J:.:ut)'.GE.NERAI. Tdcphone:+ 31(0)704103702/o-t ht: + 31 (o)jo 410 37 91. E-mail: ahmct.uzumcu(t!)opcw.urg Excellency, I have the honour to transmit to you the Third Report of the Organisation t()r the Prohibition of I Chemical Weapons Fact-Finding Mission in Syria. As you know the Mission was mandated to J I establish the !acts surrounding allegations of the usc of toxic chemicals, reportedly chlorine, f()r I hostile purposes in the Syrian Arab Republic. I This repoti will be circulated today in ·nlC I !ague to States Parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention. IIY. Mr Ban K i-tn0l)l1 Sccrdary-Gcncral ol"the United Nations United Nations llcadquartcrs New York l:>rs(olf/vof ORGANISATION FOR THE PROHIBITION OF CHEMICAL WEAPONS Dirutor-General OPCW The Hague, 18 December 2014 Johan de Witdaan 32 1./0DG/195480/14 2517 )R The Hague The Netherlands Telephone: + 31 ( o )70 416 37 02/04 Fax:+ 31 (0)70 416 37 92 E-mail: [email protected] Excellency, I have the honour to transmit to you the Third Report of the Organisation for the Prohibiti on of Chemical Weapons Fact-Finding Mission in Syria. -

September 2016

www.rbs0.com/syria37.pdf 1 Oct 2016 Page 1 of 234 Syria & Iraq: September 2016 Copyright 2016 by Ronald B. Standler No copyright claimed for quotations. No copyright claimed for works of the U.S. Government. Table of Contents 1. Chemical Weapons U.N. Security Council begins to ask who used chemical weapons in Syria? ISIL used mustard in Iraq (11 Aug 2015) 2. Syria United Nations Diverted from Syria death toll in Syria now over 301,000 (30 Sep) Free Syrian Army is Leaderless since June 2015 Turkey is an ally from Hell U.S. troops in Syria Recognition that Assad is Winning the Civil War Peace Negotiations for Syria Future of Assad must be decided by Syrians Planning for Peace Negotiations in Geneva New Russia/USA Agreements (9 Sep) U.N. Security Council meeting (21 Sep) Syrian speech to U.N. General Assembly (24 Sep) more meetings and negotiations 22-30 Sep 2016 Friends of Syria meeting in London (7 Sep) ISSG meetings (20, 22 Sep 2016) occasional reports of violations of the Cessation of Hostilities agreement proposed 48-hour ceasefires in Aleppo siege of Aleppo (1-12 Sep} Violations of new agreements in Syria (12-19 Sep) continuing civil war in Syria (20-30 Sep) bombing hospitals in Syria surrender of Moadamiyeh U.N. Reports war crimes prosecution? 3. Iraq Atrocities in Iraq No Criminal Prosecution of Iraqi Army Officers No Prosecution for Fall of Mosul No Prosecution for Rout at Ramadi No Criminal Prosecution for Employing "Ghost Soldiers" www.rbs0.com/syria37.pdf 1 Oct 2016 Page 2 of 234 Iraq is a failed nation U.S. -

5.28 M 874,814

Syrian Arab Republic: Whole of Syria Food Security Sector - Sector Objective 1 (March Plan - 2016) This map reflects the number of people reached with Life Saving Activities against the 2016 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) as part of Strategic Objective 1 Sector Objective 1(SO 1) : Provide emergency response capacity, lifesaving, and life sustaining assistance to the most vulnerable crisis affected people, including people with specific needs. 5.28 m Jawadiyah Total beneficiaries planned T U R K E Y Al Malika Quamishli Qahtaniyyeh E with food baskets (monthly Amuda 1. Rasm Haram El-Imam Darbasiyah 2. Rabee'a 3. Eastern Kwaires Lower Ain al Ya'robiyah family food ration), cash & 4. Armanaz Jarablus Shyookh Arab Bulbul 5. Kafr Takharim Al-Hasakeh Raju Sharan Ghandorah Tell Be'r Al-Hulo Tal Hmis voucher food assistance Suran Ras Al Tal ! Ar-Ra'ee Abiad Al-Wardeyyeh Ma'btali A'z!az Ain Tamer Sheikh Aghtrin Tall Menbij P Origin of assistance El-Hadid Afrin A'rima Sarin Al-Hasakeh Re!faat Abu Ein Issa Suluk Al Bab Qalqal Hole Jandairis Na!bul Mare' Daret ! Tadaf 3.2 m 2.07 m Dan!a ! Aleppo Har!im Azza 1 P! Haritan Ar-Raqqa ! !Maaret Atareb Jebel 3 Dayr Areesheh From within Syria From neighbouring Salqin!5 ! Tamsrin Saman Hafir Jurneyyeh 4 ! Zarbah countries ! ! As Safira Ar-Raqqa Shadadah Darko!sh Idle! b Hadher Karama ! Bennsh Banan Maskana P Kiseb Janudiyeh Idleb!PSarm!in Badama Mhambal ! Hajeb Qastal 2 ! ! Saraqab Abul Al-Thawrah Markada Jisr-Ash-Shugur Ariha Al-Khafsa Maadan Kisreh March-Plan vs SO1 Target Maaf ! Ma'arrat Thohur Kansaba -

Weekly Conflict Summary

Weekly Conflict Summary September 14-20, 2017 During the reporting period, pro-government forces and Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF, a Kurdish-led coalition backed by the US) both advanced around the ISIS-held city of Deir Ezzor, leading to a sharp increase in tension between the two as they maneuver close to one another. ISIS-held territory in Raqqa city continued to fall to SDF advances the reporting week and pro-government forces advanced against the group in eastern Homs/eastern Hama as well. Hai’yat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS, formerly Al-Qaeda-linked Jabhat al-Nusra) started another offensive for the northern countryside of Hama, to no real effect. A string of assassinations within Idleb targeted members of HTS. HTS formed an interim governing body to compete with the Syrian opposition’s Interim Government and a coalition of opposition forces expressed their discontent with the Astana process. Units in southern Syria have continued to develop their local police work and are aiding attempts to strengthen the Syrian opposition’s Interim Government that HTS opposes. Figure 1 - Areas of control in Syria by September 20, with arrows indicating advances since the start of the reporting period 1 of 6 Weekly Conflict Summary – September 09-14, 2017 Conflict around Deir Ezzor In the last two weeks, pro-government forces broke the ISIS siege around Deir Ezzor city, the offensive force has worked to expand its control over the city and surrounding area. This week, pro-government forces drove back ISIS fighters at least 10-15 km from the Deir Ezzor Military Airport, from which combat missions have been launched since. -

EDAM DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE SENTINEL: IDLIB on the VERGE of IMPLOSION Dr

EDAM Defense Intelligence Sentinel 2019/01 August 2019 EDAM DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE SENTINEL: IDLIB ON THE VERGE OF IMPLOSION Dr. Can Kasapoglu | Director of Security and Defense Research Program Emre Kursat Kaya | Researcher EDAM Defense Intelligence Sentinel 2019/01 EDAM DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE SENTINEL: IDLIB ON THE VERGE OF IMPLOSION Dr. Can Kasapoglu | Director of Security and Defense Research Program Emre Kursat Kaya | Researcher Greater Idlib Region and the Turkish (Blue), Russian (Red) and Iranian (Orange) observation posts - Modified map, original from Liveuamap.com What Happened? On August 19th, 2019, the Syrian Arab Air Force launched an have intensified around Maarat al-Nu’man, another M5 airstrike, halting the Turkish military convoy that was heading choke point. In the meanwhile, the Syrian Araby Army’s to the 9th observation post in Morek. (The observation posts maneuvers have effectively isolated the Turkish observation around Idlib were established as an extension of the Astana post. Furthermore, the Turkish convoy, which had been en process brokered by Russia, Turkey, and Iran). The attack route to Morek in the beginning, has set defensive positions took place along the M5 highway, north of Khan Sheikhun, in a critical location between Khan Sheikun and Maarat a critical choke-point. Subsequently, Assad’s forces have al-Nu’man. The Syrian Arab Army, supported by Russian boosted their offensive and captured the geostrategically airpower, is preparing for a robust assault in greater Idlib critical town. At present, the regime’s military activities that could exacerbate troublesome humanitarian problems. 2 EDAM Defense Intelligence Sentinel 2019/01 Significance: The regime offensive could displace millions of people Turkish forward-deployed contingents and the Syrian in Idlib and overwhelm Turkey’s security capacity to keep Arab Army’s elite units are now positioned dangerously Europe safe. -

Idlib and Its Environs Narrowing Prospects for a Rebel Holdout REUTERS/KHALIL ASHAWI REUTERS/KHALIL

THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ FEBRUARY 2020 ■ PN75 Idlib and Its Environs Narrowing Prospects for a Rebel Holdout REUTERS/KHALIL ASHAWI REUTERS/KHALIL By Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi Greater Idlib and its immediate surroundings in northwest Syria—consisting of rural northern Latakia, north- western Hama, and western Aleppo—stand out as the last segment of the country held by independent groups. These groups are primarily jihadist, Islamist, and Salafi in orientation. Other areas have returned to Syrian government control, are held by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), or are held by insurgent groups that are entirely constrained by their foreign backers; that is, these backers effectively make decisions for the insurgents. As for insurgents in this third category, the two zones of particular interest are (1) the al-Tanf pocket, held by the U.S.-backed Jaish Maghaweer al-Thawra, and (2) the areas along the northern border with Turkey, from Afrin in the west to Tal Abyad and Ras al-Ain in the east, controlled by “Syrian © 2020 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. AYMENN JAWAD AL-TAMIMI National Army” (SNA) factions that are backed by in Idlib province that remained outside insurgent control Turkey and cannot act without its approval. were the isolated Shia villages of al-Fua and Kafarya, This paper considers the development of Idlib and whose local fighters were bolstered by a small presence its environs into Syria’s last independent center for insur- of Lebanese Hezbollah personnel serving in a training gents, beginning with the province’s near-full takeover by and advisory capacity.3 the Jaish al-Fatah alliance in spring 2015 and concluding Charles Lister has pointed out that the insurgent suc- at the end of 2019, by which time Jaish al-Fatah had cesses in Idlib involved coordination among the various long ceased to exist and the jihadist group Hayat Tahrir rebel factions in the northwest. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 16 August 2013

United Nations A/HRC/24/46 General Assembly Distr.: General 16 August 2013 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fourth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Report of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic* Summary The Syrian Arab Republic is a battlefield. Its cities and towns suffer relentless shelling and sieges. Massacres are perpetrated with impunity. An untold number of Syrians have disappeared. The present report covers investigations conducted from 15 May to 15 July 2013. Its findings are based on 258 interviews and other collected evidence. Government and pro-government forces have continued to conduct widespread attacks on the civilian population, committing murder, torture, rape and enforced disappearance as crimes against humanity. They have laid siege to neighbourhoods and subjected them to indiscriminate shelling. Government forces have committed gross violations of human rights and the war crimes of torture, hostage-taking, murder, execution without due process, rape, attacking protected objects and pillage. Anti-government armed groups have committed war crimes, including murder, execution without due process, torture, hostage-taking and attacking protected objects. They have besieged and indiscriminately shelled civilian neighbourhoods. Anti-government and Kurdish armed groups have recruited and used child soldiers in hostilities. The perpetrators of these violations and crimes, on all sides, act in defiance of international law. They do not fear accountability. Referral to justice is imperative. There is no military solution to this conflict. Those who supply arms create but an illusion of victory. A political solution founded upon tenets of the Geneva communiqué is the only path to peace. -

Martin Et Al, the Future of Chemical Weapons Final Authors' Version 16.2

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/09636412.2018.1483640 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Chapman, G., Elbahtimy, H., & Martin, S. B. (2018). The Future of Chemical Weapons: Implications of the Lack of Military Utility in the Syrian Civil War. SECURITY STUDIES, 27(4), 704-733. https://doi.org/10.1080/09636412.2018.1483640 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

The Tiger Forces Pro-Assad Fighters Backed by Russia

THE TIGER FORCES PRO-ASSAD FIGHTERS BACKED BY RUSSIA GREGORY WATERS OCTOBER 2018 POLICY PAPER 2018-10 CONTENTS * SUMMARY * KEY POINTS * 1 METHODOLOGY * 1 ORIGINS AND HISTORY * 3 RESTRUCTURING * 6 THE TIGER FORCES IN 2018 * 8 TIGER FORCES GROUPS * 22 ENDNOTES * 23 ABOUT THE AUTHOR * 24 ABOUT THE MIDDLE EAST INSTITUTE © The Middle East Institute The Middle East Institute 1319 18th Street NW Washington, D.C. 20036 SUMMARY The Tiger Forces is a Syrian Air Intelligence-affiliated militia fighting for the Syrian government and backed by Russia. While often described as the Syrian government’s elite fighting force, this research portrays a starkly different picture. The Tiger Forces are the largest single fighting force on the Syrian battlefield, with approximately 24 groups comprised of some 4,000 offensive infantry units as well as a dedicated artillery regiment and armor unit of unknown size. Beyond these fighters are thousands of additional so- called flex units, affiliated militiamen who remain largely garrisoned in their hometowns along the north Hama and Homs borders until called on to join offensives as needed. Despite a decentralized command structure, the Tiger Forces’ capabilities far exceed any other unit currently fighting in the Syrian civil war. The main source of the unit’s success stems from its two full-strength infantry brigades with dedicated logistical support and the ability to call on the Syrian air force—and after September 2015 the Russian air force—at will. While there is likely some degree of higher-than-average competence among the Tiger Forces’ officer corps, this research demonstrates that the true power of the unit does not come from their alleged status as elite fighters but instead from their large size, supply lines, and Russian support. -

Syr Northern Humanitarian Das

Syrian Arab Republic: Humanitarian Dashboard - Eight Governorates June 2014 (Issued on 30 Jul 2014) SITUATION OVERVIEW With regard to the overall situation, continued conflict between various armed opposition groups has blocked many key access routes to many areas from inside Syria. ISIS and other armed opposition groups fought intensely for the control of Aleppo, southern Al-Hasakeh and Deir-ez-Zor, with ISIS consolidating control of most of Deir-ez-Zor governorate and launching an offensive on opposition positions in Northern rural Aleppo. This prompted ISIS and armed opposition groups to engage in reciprocal blocks on humanitarian access, with a significant impact in eastern rural Aleppo, Deir-ez-Zor, Al- Hasakeh and Ar-Raqqa governorates. June also saw an increase in bombardment by the Government of Syria on ISIS-held territories and positions, especially in Ar-Raqqa. Opposition forces advanced on government-controlled positions in Northern Hama around Morek, displacing tens of thousands towards the Turkish border. Government forces also continued to advance incrementally around the North-East of Aleppo city, blocking the main access route into opposition-controlled eastern Aleppo city and intensely bombarding and shelling the only remaining routes – Handarat and Castello, sustaining fears that the government would soon seal off all access to the East of the city. Opposition forces withdrew from Kassab in Lattakia, reopening humanitarian access to the town from government-held areas. As a result, protection of civilians and the most vulnerable remains one of the major concerns of the humanitarian community. Over the reporting period approximately 500,000 beneficiaries have been assisted with food by the Turkey based partners.