Church Or Museum? Tourists, Tickets and Transformations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toskana Kulturrouten

TOSKANA KULTURROUTEN Auf der Entdeckung großer Genies: die schöpferische Geisterkraft von Wissenschaftlern, historische Persönlichkeiten, Dichtern und Musikern toskana KULTURROUTEN Auf der Entdeckung großer Genies: die schöpferische Geisterkraft von Wissenschaftlern, historische Persönlichkeiten, Dichtern und Musikern Ein Reiseführer, der zum ersten Mal dazu einlädt, Dichter und Musiker, Wissen- schaftler und Ordensleute, Politiker und Revolutionäre sowie wichtige histori- sche Persönlichkeiten zu entdecken, die im Lauf der Jahrhunderte in der Toskana geboren wurden oder hier gelebt haben und hier ihre unauslöschlichen Spuren hinterlassen haben, um diese Region in der ganzen Welt berühmt zu machen. Dem Leben und Arbeiten dieser Genies folgend hat der Reisende Seite für Seite die Möglichkeit, durch ihre Erfindungen, ihre Worte und ihre Musik eine etwas andere Toskana zu entdecken, neue Wege, die ihn in Städte und Dörfer, an be- rühmte Orte und in versteckte Nischen entführen. Auch für ihre Bewohner selbst eine neue Form, um die Region wahrzunehmen und mehr über die Werke großer Persönlichkeiten der Geschichte zu erfahren, denen die Plätze und Straßen unse- res Landes gewidmet sind. Die Toskana ist ein Land, das seit jeher als Quelle der Inspiration für große Männer und Frauen fungiert: Über ihre Biografien und die Orte, an denen sie gelebt und gearbeitet haben, sowie mit Hilfe einer Vielzahl an Bildern und Darstellungen ent- decken wir mit diesem Reiseführer einen neuen Weg, um die wahre Seele dieser außerordentlichen Region zu verstehen -

The Armstrong Browning Library Newsletter God Is the Perfect Poet

The Armstrong Browning Library Newsletter God is the perfect poet. – Paracelsus by Robert Browning NUMBER 51 SPRING/SUMMER 2007 WACO, TEXAS Ann Miller to be Honored at ABL For more than half a century, the find inspiration. She wrote to her sister late Professor Ann Vardaman Miller of spending most of the summer there was connected to Baylor’s English in the “monastery like an eagle’s nest Department—first as a student (she . in the midst of mountains, rocks, earned a B.A. in 1949, serving as an precipices, waterfalls, drifts of snow, assistant to Dr. A. J. Armstrong, and a and magnificent chestnut forests.” master’s in 1951) and eventually as a Master Teacher of English herself. So Getting to Vallombrosa was not it is fitting that a former student has easy. First, the Brownings had to stepped forward to provide a tribute obtain permission for the visit from to the legendary Miller in Armstrong the Archbishop of Florence and the Browning Library, the location of her Abbot-General. Then, the trip itself first campus office. was arduous—it involved sitting in a wine basket while being dragged up the An anonymous donor has begun the cliffs by oxen. At the top, the scenery process of dedicating a stained glass was all the Brownings had dreamed window in the Cox Reception Hall, on of, but disappointment awaited Barrett the ground floor of the library, to Miller. Browning. The monks of the monastery The Vallombrosa Window in ABL’s Cox Reception The hall is already home to five windows, could not be persuaded to allow a woman Hall will be dedicated to the late Ann Miller, a Baylor professor and former student of Dr. -

Painting Perspective & Emotion Harmonizing Classical Humanism W

Quattrocento: Painting Perspective & emotion Harmonizing classical humanism w/ Christian Church Linear perspective – single point perspective Develops in Florence ~1420s Study of perspective Brunelleschi & Alberti Rules of Perspective (published 1435) Rule 1: There is no distortion of straight lines Rule 2: There is no distortion of objects parallel to the picture plane Rule 3: Orthogonal lines converge in a single vanishing point depending on the position of the viewer’s eye Rule 4: Size diminishes relative to distance. Size reflected importance in medieval times In Renaissance all figures must obey the rules Perspective = rationalization of vision Beauty in mathematics Chiaroscuro – use of strong external light source to create volume Transition over 15 th century Start: Expensive materials (oooh & aaah factor) Gold & Ultramarine Lapis Lazuli powder End: Skill & Reputation Names matter Skill at perspective Madonna and Child (1426), Masaccio Artist intentionally created problems to solve – demonstrating skill ☺ Agonistic Masaccio Dramatic shift in painting in form & content Emotion, external lighting (chiaroscuro) Mathematically constructed space Holy Trinity (ca. 1428) Santa Maria Novella, Florence Patron: Lorenzo Lenzi Single point perspective – vanishing point Figures within and outside the structure Status shown by arrangement Trinity literally and symbolically Vertical arrangement for equality Tribute Money (ca. 1427) Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence Vanishing point at Christ’s head Three points in story Unusual -

Tour Violet – Flowers and Villas of Tuscany

The Italian specialist for group tours Botanico - Tour Violet – Flowers and Villas of The tour includes: Tuscany - 6 Days Transportation and Hotels - Arrival transfer from Florence Airport to the hotel Florence - Pisa - Lucca - Siena - San Gimignano and Volterra in Florence - Departure transfer from the hotel to Florence Airport Tuscany's magigal Gardens and Villas - Deluxe AC motor-coach as per the above itinerary - 5 nights at a 4*Hotel Diplomat or similar Food and Drinks ITINERARY - 5 buffet breakfasts - 1 dinner at the hotel on arrival day Day 1: Arrive in Florence Experiences and Services Arrival transfer from Florence Airport to the hotel in Florence. Check-in, welcome drink - 5 hour city tour of Florence with English speaking guide and rest of the day at leisure. - Entrance fee to Boboli Gardens Hotel in Florence MEALS D - Entrance fee to Villa Bardini Gardens - 2 hour city tour of Pisa with English speaking guide Day 2: Florence - Entrance fee to the Botanical Garden in Pisa - 2 hour city tour of Siena with English speaking Boboli Garden and Villa Bardini‘s Garden guide The art and cultural metropolis of Florence is a must for all travelers to Tuscany. The - Entrance fee to Villa Geggiano Cathedral dominates the cityscape and together with the Campanile and the Baptistery - English-speaking botanical tour escort throughout forms one of the most magnificent works of art in the world. The austerity and beauty the tour - Porterage on arrival and departure at the hotel of this city and the pride of the Florentines is manifested in an unique way in the - Headsets throughout the tour Palazzo Vecchio. -

Florence Next Time Contents & Introduction

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Conventional names for traditional religious subjects in Renaissance art The Cathedral of Florence (Duomo) The Baptistery Museo dell’Opera del Duomo The other Basilicas of Florence Introduction Santissima Annunciata Santa Croce and Museum San Lorenzo and Medici Chapels San Marco and Museum Santa Maria del Carmine and Brancacci Chapel Santa Maria Novella and Museum San Miniato al Monte Santo Spirito and Museum Santa Trinita Florence’s other churches Ognissanti Orsanmichele and Museum Santi Apostoli Sant’Ambrogio San Frediano in Cestello San Felice in Piazza San Filippo Neri San Remigio Last Suppers Sant’Apollonia Ognissanti Foligno San Salvi San Marco Santa Croce Santa Maria Novella and Santo Spirito Tours of Major Galleries Tour One – Uffizi Tour Two – Bargello Tour Three – Accademia Tour Four – Palatine Gallery Museum Tours Palazzo Vecchio Museo Stefano Bardini Museo Bandini at Fiesole Other Museums - Pitti, La Specola, Horne, Galileo Ten Lesser-known Treasures Chiostro dello Scalzo Santa Maria Maggiore – the Coppovaldo Loggia del Bigallo San Michele Visdomini – Pontormo’s Madonna with Child and Saints The Chimera of Arezzo Perugino’s Crucifixion at Santa Maria dei Pazzi The Badia Fiorentina and Chiostro degli Aranci The Madonna of the Stairs and Battle of the Centaurs by Michelangelo The Cappella dei Magi, Palazzo Medici-Riccardi The Capponi Chapel at Santa Felicita Biographies of the Artists Glossary of Terms Bibliography SimplifiedTime-line diagram Index INTRODUCTION There can’t be many people who love art who won’t at some time in their lives find themselves in Florence, expecting to see and appreciate the incredibly beautiful paintings and sculptures collected in that little city. -

Francesca Coccolo, Rodolfo Siviero Between Fascism and the Cold

STUDI DI MEMOFONTE Rivista on-line semestrale Numero 22/2019 FONDAZIONE MEMOFONTE Studio per l’elaborazione informatica delle fonti storico-artistiche www.memofonte.it COMITATO REDAZIONALE Proprietario Fondazione Memofonte onlus Fondatrice Paola Barocchi Direzione scientifica Donata Levi Comitato scientifico Francesco Caglioti, Barbara Cinelli, Flavio Fergonzi, Margaret Haines, Donata Levi, Nicoletta Maraschio, Carmelo Occhipinti Cura scientifica Daria Brasca, Christian Fuhrmeister, Emanuele Pellegrini Cura redazionale Martina Nastasi, Laurence Connell Segreteria di redazione Fondazione Memofonte onlus, via de’ Coverelli 2/4, 50125 Firenze [email protected] ISSN 2038-0488 INDICE The Transfer of Jewish-owned Cultural Objects in the Alpe Adria Region DARIA BRASCA, CHRISTIAN FUHRMEISTER, EMANUELE PELLEGRINI Introduction p. 1 VICTORIA REED Museum Acquisitions in the Era of the Washington Principles: Porcelain from the Emma Budge Estate p. 9 GISÈLE LÉVY Looting Jewish Heritage in the Alpe Adria Region. Findings from the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities (UCEI) Historical Archives p. 28 IVA PASINI TRŽEC Contentious Musealisation Process(es) of Jewish Art Collections in Croatia p. 41 DARIJA ALUJEVIĆ Jewish-owned Art Collections in Zagreb: The Destiny of the Robert Deutsch Maceljski Collection p. 50 ANTONIJA MLIKOTA The Destiny of the Tilla Durieux Collection after its Transfer from Berlin to Zagreb p. 64 DARIA BRASCA The Dispossession of Italian Jews: the Fate of Cultural Property in the Alpe Adria Region during Second World War p. 79 CAMILLA DA DALT The Case of Morpurgo De Nilma’s Art Collection in Trieste: from a Jewish Legacy to a ‘German Donation’ p. 107 CRISTINA CUDICIO The Dissolution of a Jewish Collection: the Pincherle Family in Trieste p. -

Romantic Italian Holiday – London to Florence

Romantic Italian Holiday – London to Florence https://www.irtsociety.com/journey/romantic-italian-holiday-london-to-florence/ Overview The Highlights - Two nights at the five-star Villa San Michele, a former monastery overlooking the Renaissance city of Florence - Two nights at the palatial Cipriani Hotel in Venice, perfectly situated just minutes from the Piazza San Marco, yet blissfully removed from the tourist crush The Society of International Railway Travelers | irtsociety.com | (800) 478-4881 Page 1/6 - Double compartment Venice-Paris-Calais on the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express - Afternoon tea, wine and champagne on the British Pullman from the English Channel to London - Sumptuous breakfast daily at your hotels - Private guide/driver for half-day each in Florence & Venice - First-class, high-speed-rail tickets Florence-Venice - Airport/rail station/hotel transfers Florence & Venice The Tour Try this for Romance: two nights in Florence at the Belmond Villa San Michele, a former monastery turned five-star hotel; two nights in Venice at the Belmond Hotel Cipriani, iconic waterside pleasure palace overlooking the Grand Canal; two days and a night on the Venice Simplon-Orient-Express, capped off by afternoon tea on the British Pullman into London. Perfect for honeymoons, anniversary celebrations, or any other occasion demanding over-the-top luxury and romance. Package includes hotels, breakfast daily, railway station/airport/hotel transfers, tours, Florence-Venice high-speed rail transfer, and more. Extend your celebration: add London's romantic Milestone Hotel for a two-night stay and enjoy complimentary afternoon tea for two. Special Report: View travel notes by Society owners Owen & Eleanor Hardy, who celebrated their 30th wedding anniversary on the Orient-Express Venice-Paris-London. -

Cultural Heritage Of

® LIFE BIENNIAL BEYOND TOURISM® PUBBLICATION EVENTS 2014 - 2016 MEETING THE WORLD IN FLORENCE Centro Congressi al Duomo Life Beyond Tourism® Events Director | Direttore Carlotta Del Bianco Coordinator | Responsabile Michaela Žáčková Rossi Organizing Secretariat | Segreteria Organizzativa Stefania Macrì Eleonora Catalano Zdenka Skorunkova Dati Chika Arai Publication edited by | Pubblicazione a cura di Centro Congressi al Duomo: Life Beyond Tourism® Events With the collaboration of | Con la collaborazione di Centro Congressi al Duomo: Hotel Laurus al Duomo Hotel Pitti Palace al Ponte Vecchio Design and layout | Progetto grafico e impaginazione Corinna Del Bianco Maria Paz Soffia Contents | Contenuti Life Beyond Tourism® Events Abstracts texts have been sent to Life Beyond Tourism® Events by the Project Leaders of each conference and workshop – promoted by the Fondazione Romualdo Del Bianco® of Florence. I testi degli abstract di convegni e workshop – promossi dalla Fondazione Romualdo Del Bianco® – sono stati forniti a Life Beyond Tourism® Events dai Project Leader degli stessi eventi. Translation | Traduzione Eleonora Catalano Masso delle Fate Edizioni Via Cavalcanti 9/D - 50058 Signa (FI) ©Fondazione Romualdo Del Bianco® - Life Beyond Tourism® Masso delle Fate Edizioni ISBN LIFE BIENNIAL BEYOND TOURISM® PUBBLICATION EVENTS 2014 - 2016 Our ability to reach unity in diversity will be the perfect present for the test oF our civilization MAHATMA GANDHI Welcome to Florence! In order to offer the travellers support to their Florence, a personal and professional Florentine journey, the Centro Congressi al Duomo has established an event planning section called Life Beyond Tourism® city frozen in Events, which for years has been organizing in Florence international and intercultural events. -

The Best of Renaissance Florence April 28 – May 6, 2019

Alumni Travel Study From Galleries to Gardens The Best of Renaissance Florence April 28 – May 6, 2019 Featuring Study Leader Molly Bourne ’87, Professor of Art History and Coordinator of the Master’s Program in Renaissance Art at Syracuse University Florence Immerse yourself in the tranquil, elegant beauty of Italy’s grandest gardens and noble estates. Discover the beauty, drama, and creativity of the Italian Renaissance by spending a week in Florence—the “Cradle of the Renaissance”—with fellow Williams College alumni. In addition to a dazzling array of special openings, invitations into private homes, and splendid feasts of Tuscan cuisine, this tour offers the academic leadership of Molly Bourne (Williams Class of ’87), art history professor at Syracuse University Florence. From the early innovations of Giotto, Brunelleschi, and Masaccio to the grand accomplishments of Michelangelo, our itinerary will uncover the very best of Florence’s Renaissance treasury. Outside of Florence, excursions to delightful Siena and along the Piero della Francesca trail will provide perspectives on the rise of the Renaissance in Tuscany. But the program is not merely an art seminar—interactions with local food and wine experts, lunches inside beautiful private homes, meanders through stunning private gardens, and meetings with traditional artisans will complement this unforgettable journey. Study Leader MOLLY BOURNE (BA Williams ’87; PhD Harvard ’98) has taught art history at Syracuse University Florence since 1999, where she is also Coordinator of their Master’s Program in Renaissance Art History. A member of the Accademia Nazionale Virgiliana, she has also served as project researcher for the Medici Archive Project and held a fellowship at Villa I Tatti, the Harvard Center for Renaissance Studies. -

BG Research Online

BG Research Online Capancioni, C. (2017). Janet Ross’s intergenerational life writing: female intellectual legacy through memoirs, correspondence, and reminiscences. Life Writing, 14(2), 233-244. This is an Accepted Manuscript published by Taylor & Francis in its final form on 3 April 2017 at http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14484528.2017.1291251. This version may differ slightly from the final published version. Copyright is retained by the author/s and/or other copyright holders. End users generally may reproduce, display or distribute single copies of content held within BG Research Online, in any format or medium, for personal research & study or for educational or other not-for-profit purposes provided that: The full bibliographic details and a hyperlink to (or the URL of) the item’s record in BG Research Online are clearly displayed; No part of the content or metadata is further copied, reproduced, distributed, displayed or published, in any format or medium; The content and/or metadata is not used for commercial purposes; The content is not altered or adapted without written permission from the rights owner/s, unless expressly permitted by licence. For other BG Research Online policies see http://researchonline.bishopg.ac.uk/policies.html. For enquiries about BG Research Online email [email protected]. Janet Ross’s Intergenerational Life Writing: Female Intellectual Legacy through Memoirs, Correspondence, and Reminiscences Claudia Capancioni, School of Humanities, Bishop Grosseteste University, Lincoln, UK Dr. Claudia Capancioni, School of Humanities, Bishop Grosseteste University, Lincoln, LN1 3DY [email protected] Dr Claudia Capancioni is Senior Lecturer and Academic Co-ordinator for English at Bishop Grosseteste University, Lincoln (UK) where she has led the English Department since 2013. -

"Nuper Rosarum Flores" and the Cathedral of Florence Author(S): Marvin Trachtenberg Source: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol

Architecture and Music Reunited: A New Reading of Dufay's "Nuper Rosarum Flores" and the Cathedral of Florence Author(s): Marvin Trachtenberg Source: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Autumn, 2001), pp. 740-775 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Renaissance Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1261923 . Accessed: 03/11/2014 00:42 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Renaissance Society of America are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Renaissance Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 192.147.172.89 on Mon, 3 Nov 2014 00:42:52 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Architectureand Alusic Reunited: .V A lVewReadi 0 u S uperRosarum Floresand theCathedral ofFlorence. byMARVIN TRACHTENBERG Theproportions of the voices are harmoniesforthe ears; those of the measure- mentsare harmoniesforthe eyes. Such harmoniesusuallyplease very much, withoutanyone knowing why, excepting the student of the causality of things. -Palladio O 567) Thechiasmatic themes ofarchitecture asfrozen mu-sic and mu-sicas singingthe architecture ofthe worldrun as leitmotifithrough the histories ofphilosophy, music, and architecture.Rarely, however,can historical intersections ofthese practices be identified. -

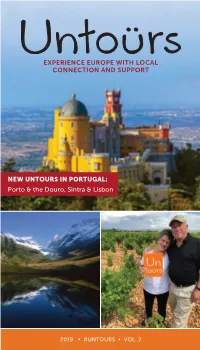

Experience Europe with Local Connection and Support

EXPERIENCE EUROPE WITH LOCAL CONNECTION AND SUPPORT NEW UNTOURS IN PORTUGAL: Porto & the Douro, Sintra & Lisbon 2019 • #UNTOURS • VOL. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS UNTOURS & VENTURES ICELAND PORTUGAL Ventures Cruises ......................................25 NEW, Sintra .....................................................6 SWITZERLAND NEW, Porto ..................................................... 7 Heartland & Oberland ..................... 26-27 SPAIN GERMANY Barcelona ........................................................8 The Rhine ..................................................28 Andalusia .........................................................9 The Castle .................................................29 ITALY Rhine & Danube River Cruises ............. 30 Tuscany ......................................................10 HOLLAND Umbria ....................................................... 11 Leiden ............................................................ 31 Venice ........................................................ 12 AUSTRIA Florence .................................................... 13 Salzburg .....................................................32 Rome..........................................................14 Vienna ........................................................33 Amalfi Coast ............................................. 15 EASTERN EUROPE FRANCE Prague ........................................................34 Provence ...................................................16 Budapest ...................................................35