Bulletin 425 February 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beaufort Family

FRIENDS OF WOKING PALACE The Beaufort Family The Beauforts were the children of John of Gaunt and his mistress, Katherine Swynford. Although the children were born whilst John was married to Constance, Queen of Castile, the line was legitimised by Papal Bull and Act of Parliament and became the House of Tudor in 1485 when Henry VII defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field. The connection of the Beauforts with Woking house began when John Beaufort married Margaret Holland the sister and coheir of the childless Edmund Holland, Earl of Kent. John Beaufort, (c1371-16 March 1409/10) illegitimate son of John of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford created Earl of Somerset 9 February 1396/7 and Marquess of Dorset and Marquess of Somerset 29 September 1397, married before 28 September 1397, Margaret Holland, daughter, Thomas, Earl of Kent John died 16 March 1409/10 in the hospital of St Catherine by the Tower of London and was buried in St Michael's chapel in Canterbury Cathedral. His widow married secondly Thomas, Duke of Clarence (1387-1421) see later. TCP John, Duke of Somerset son of above died 27 May 1444 married Margaret Beauchamp of Bletso in or about 1442, widow of Sir Oliver St John, sister and heir of John, Lord Beauchamp, created Earl of Kendal and Duke of Somerset 28 August 1443. After the death of John, Duke of Somerset, his wife married Leo Welles who was slain at Towton 29 March 1461. She died at a great age shortly before 3 June 1482. The only child and heir of this marriage was Lady Margaret Beaufort born 31 May 1443. -

Farnham, Surrey, GU10 1RB

www.andrewlodge.co.uk Rosemont, Temple's Close Moor Park, Farnham, Surrey, GU10 1RB Price Guide £1,900,000 Farnham 28 Downing Street, Farnham, Surrey GU9 7PD 01252 717705 An opportunity to acquire an immaculately presented, modern detached family home, set in beautiful gardens in excess of 1.6 acres, in London this much sought after private close in Moor Representative Office Park, offering ample scope to extend 119 Park Lane, Mayfair, London W1 020 7079 1400 • 4 double bedrooms • Boiler room and covered • 2 en-suite shower rooms. utility lobby (1 Jack & Jill) • Swimming pool with • Family bathroom changing rooms • Triple aspect drawing room • Double garage with workshop and freezer area • Elegant dining room • Further detached garage • Well fitted kitchen/ workshop to take a boat breakfast room • 4 outbuildings • Study • Approximately one acre of beautiful formal gardens • Over half an acre of www.andrewlodge.co.uk wooded area with [email protected] woodland walk Rosemont, Temple's Close, Moor Park, Farnham, Surrey, Rosemont, Temple's Close, Moor Park, Farnham, Surrey, KEY FEATURES INCLUDE: * Hardwood front door opening to light and spacious reception hall with tiled floor and stairs to first floor. Door to LOCATION Cloakroom with w.c and wash hand basin. * Farnham town centre approximately 2 miles (Waterloo from 53 minutes) * Guildford 8 miles (Waterloo from 38 minutes) * Fine sitting room with feature marble fireplace housing brass gas coal fire with flames with remote control ignition * A31 2 miles, A3 7 miles, London 40 miles and adjustment, two wall painting illuminated lights, surround sound speakers in ceiling, two sets of casement sliding (All distances and times are approximate) doors to garden, triple aspect. -

Fishers Farm

1 Fishers Farm Listing The house is Grade II * listed, the description being as follows: House. C15 with C17 extensions to the rear, late C18 front. Timber framed core, brick cladding, red brick to the rear, yellow to front; plain tiled hipped roofs with centre ridge stack to front and large diagonal stacks with moulded tops to the rear. Main front with 2 rear wings at right angles with lobby entrance. 2 storeys, brick hand over ground floor and to base of parapet, quoined angles. 5 bays to front, glazing bar sash windows under gauged camber heads; blocked window on red brick surround with cill brackets to first floor centre. Central six panelled door, with traceried fanlight in a surround of Doric half columns supporting an open pediment. C19 single storey weatherboard addition to the right. Rear: two wings connected by arched entrance screen wall, brick bands over the ground floor. Interior: Extensive framing of substantial scantling exposed in left wing, deep brick fireplaces with wooden lintels. Fine Jacobean style staircase with turned balusters, scroll spiked newel posts and SS carving to underside of staircase arch 2 Period The listing suggests the date of the first build as being in the 15th century which would place the original house in the Medieval period. The front certainly looks to be an added 18th century one. Assuming the 15th century date to be correct, one would expect to find a hipped roof see photograph above with flatways rafters and/or flat joists plus jowled posts. Although the reported earliest known date of 1527 is in the Tudor period, there is no reason why the house should not be earlier. -

Council Meeting Agenda

FARNHAM TOWN COUNCIL Agenda Full Council Time and date 7.00pm on Thursday 24th September 2015 Place The Council Chamber, South Street, Farnham, GU9 7RN TO: ALL MEMBERS OF THE COUNCIL Dear Councillor You are hereby summoned to attend a Meeting of FARNHAM TOWN COUNCIL to be held on THURSDAY 24 September 2015, at 7.00PM, in the COUNCIL CHAMBER, SOUTH STREET, FARNHAM, SURREY GU9 7RN. The Agenda for the meeting is attached Yours sincerely Iain Lynch Town Clerk Members’ Apologies Members are requested to submit their apologies and any Declarations of Interest on the relevant form attached to this agenda to Ginny Gordon, by 5 pm on the day before the meeting. Recording of Council Meetings This meeting is digitally recorded for the use of the Council only. Members of the public may be recorded or photographed during the meeting and should advise the Clerk prior to the meeting if there are any concerns about this. Members of the Public are welcome and have a right to attend this Meeting. Please note that there is a maximum capacity of 30 in the public gallery 1 FARNHAM TOWN COUNCIL Disclosure of Interests Form Notification by a Member of a disclosable pecuniary interest in a matter under consideration at a meeting (Localism Act 2011). Please use the form below to state in which Agenda Items you have an interest. If you have a disclosable pecuniary or other interest in an item, please indicate whether you wish to speak (refer to Farnham Town Council’s Code of Conduct for details) As required by the Localism Act 2011, I HEREBY Declare, that I have a disclosable pecuniary or personal interest in the following matter(s). -

Council Meeting Minutes – 2 November

FARNHAM TOWN COUNCIL A Minutes Council Time and date 7.00pm on Thursday 2nd November 2017 Place The Council Chamber, South Street, Farnham Councillors * Mike Hodge * David Attfield * David Beaman * Carole Cockburn * Paula Dunsmore * John Scotty Fraser * Pat Frost * Jill Hargreaves * Stephen Hill * Sam Hollins-Owen * Mike Hyman A Andy Macleod * Kika Mirylees A Julia Potts * Susan Redfern * Jeremy Ricketts * John Ward A John Williamson * Present A Apologies for absence Officers Present: Iain Lynch (Town Clerk), Stephanie Spence (Corporate Governance Officer) There were 6 members of the public in attendance. Prior to the meeting, prayers were said by Rev Hannah Moore, Parish of Badshot Lea and Hale. C088/17 Apologies for Absence Apologies were received from Cllr Potts, Cllr Williamson and Cllr MacLeod. C089/17 Minutes The Minutes of the Farnham Town Council Meeting held on 21st September were agreed and signed by the Mayor as a correct record. C090/17 Declarations of interests Apart from the standard declarations of personal interest by councillors and by those who were dual or triple hatted by virtue of being elected to Waverley Borough Council or Surrey County Council, there were no other disclosures of interest made. C091/17 Questions and Statements by the Public There was a question from George Hesse who asked what could be done to improve the ongoing issues at the Library Gardens. The Town Clerk advised that several attempts had been made by FTC to take on the running of the gardens from SCC, but as yet no solution had been reached. Members at Strategy & Finance had agreed that a long term solution was preferred and officers were reviewing cost options. -

Surrey. Farnham

DIRECTORY.] SURREY. FARNHAM. 193 Chrystie Col. George, Shortheath lodge, Farnham Cust.om.~ & ExciRe Office, 18 Borough, John Atkinson, officer Coleman William Thomas eso. 31 Castle street, Famham Farnham Institute, South street, Frank Holland, sec Corn be Richard esq. Pierrepont, Frensham, Famham Farnham 1\farket House & Town Hall Co. Limited, Ernest Cooke Temple esq. Edmonscote, Frimley, Farnborough Crundwell, hon. sec. ; office, Town hall, Castle street Fitzroy Lt.-Col. Edward Albert, Hale Place, Farnham Farnham Swimming Baths, South street, C. E. Borelli,hon.sec Goldney Frederick Hastings esq. Prior Place, Camberley Farnham Urban District Council Sewage Pumping Station, Grove Brig.-Gen. Edward Aickin Willia.m Stewart c.B. Red.hill Guildford road, Robert William Cass, surveyor cottage, Tilford, Farnham Stamp Office, 107 West- street, Frederick William Charley, Hollings Herbert John Butler esq. D.L. The Watchetts, distributor Frimley, Farnborough Trimmer's Cottage Hospital, East street, H. F. Eala.nd Kingham Ro bert Dixon esq. Summer court, near Farnham L.R.C.P.&s.Edin. J. Hussey M.D. S. G. Slom'l.n L.R.C.P.LOnd. Latha.m Morton esq. Hollowdene, Frensham. Farnham & C. E. Tanner M.D. hon. medical officers; E. Crundwell, McLaren Ja.mes esq. Fir acre, Ash Vale, Aldershot hon. sec. ; Miss Frances Archibald, matron Mangles Frank esq. Shalden lodge, Alton Volunteer Fire Brigade Engine House, South street ; John Pain Arthur Cadlick esq. St. Catherine's, Frimley Hawkes, superintendent ; J. H. Chitty, assistant superin· Rideal Samuel esq. The Chalet, Elstead tendent & hon. sec. & 21 men Rowden Aldred Willia.m esq. K.C. 16 Stanhope gardens, London s w TERRITORIAL FORCE. -

Tilford and Crooksbury Hill

point your feet on a new path Tilford and Crooksbury Hill Distance: 10 km=6 miles easy-to-moderate walking Region: Surrey Date written: 9-sep-2013 Author: Schwebefuss Last update: 6-feb-2021 Refreshments: Charleshill, Tilford Map: Explorer 145 (Guildford) but the maps in this guide should be sufficient Problems, changes? We depend on your feedback: [email protected] Public rights are restricted to printing, copying or distributing this document exactly as seen here, complete and without any cutting or editing. See Principles on main webpage. Hill, views, pines, village, pubs, woodland, heath In Brief This is a classic walk through heaths, birchwoods and pinewoods of the sandy parts of Surrey near the River Wey, with an easy climb to the summit of a well- known hill from which you have some of the best views in the county. There is a patch of nettles on this walk in summer so shorts may be unwise but otherwise any kind of attire should be fine. There are a few muddy patches on the path from Tilford, so you may prefer to wear waterproof footwear in a very wet season. There are no stiles and only a small stretch of road with no footway, so this walk would be fine for your dog. The walk begins at the Crooksbury Hill car park off Crooksbury Road, The Sands, near Farnham, Surrey, approximate postcode GU10 1RF , grid ref. SU877458. The car park is, down a short track diagonally off the road on the north side, under a bar. It now (2015) has a new sign Crooksbury Hill . -

Meetings, Agendas, and Minutes

FARNHAM TOWN COUNCIL F Notes Planning & Licensing Consultative Working Group Time and date 9.30 am on Monday 12th August, 2019 Place Council Chamber, Farnham Town Council, South Street, Farnham GU9 7RN Planning & Licensing Consultative Working Group Members Present: Councillor Brian Edmonds (Lead Member) Councillor David Beaman Councillor Roger Blishen Councillor Alan Earwaker Councillor John "Scotty" Fraser Councillor Michaela Martin Councillor John Neale Officers: Jenny De Quervain (Planning & Civic Administrator) 1. Waverley Borough Council Planning Portal Val Jacobi, Paul Reeves and Patrick Arthur, Waverley Borough Council Waverley Borough Council Officers in attendance to give advice and review external use of Civica. 2. Apologies for Absence Councillors Gray and Hesse. 3. Disclosure of Interests None were received. 4. Applicatio ns for larger developments Farnham Upper Hale WA/2019/1167 Farnham Upper Hale Officer: Louise Fuller Display of non-illuminated signs. THE FOLLY, 1 FOLLY HILL, FARNHAM GU9 0AX Farnham Town Council objects to the proposed size and position of the signage being a danger to drivers and would require a reduction in height of the green boundary. Signage for the development should be restricted to the site entrance and reduced in size to limit the distraction to road users. WA/2019/1195 Farnham Upper Hale Officer: Graham Speller Erection of 5 dwellings, alterations to access and associated works following demolition of existing outbuildings. LAND AT 108 FOXDENE, UPPER HALE ROAD, FARNHAM GU9 0JW Farnham Town Council objects to the overdevelopment of the Land at 108 Foxdene not being compliant with the Farnham Design Statement and Farnham Neighbourhood Plan Policy FNP1 in layout and density. -

Tilford Life the Tilford Parish Council Newsletter

Tilford Life The Tilford Parish Council Newsletter In This Issue ....... P2 Heather Humphrey’s Bench / All Saints Grand Opening P3 Broadband Improvements beckon / 9 Armistice Celebration Dinner P4 Changes at the Parish Council. / News from The Duke of y 201 Cambridge / Dinner Winner ruar P5 Tilford Gardening Club Feb / Tilford Women’s Institute / 1st Tilford Brownies ary - P6 Did you know! / Ironstone Janu P7 Tilford Badminton Club Night / Chair Job / Tilford and Issue 25 Rushmoor Calendar 2019 P8 Young Tilford It is proposed to have this all installed & Wood Stone specialist https://www. East Bridge Renovation by mid-March. Once the start date is putneyandwood.co.uk. During the confirmed, advanced warning signs works, the riverside carpark will be will be put up. The road will not required for storage use from 4th It’s gone all a bit quiet on the East be closed for the erection of the February 2019 till the end of the Bridge renovation conversation of temporary footbridge but the road whole scheme so will be partially late but not to disappoint, Shaan Ali, will be closed for traffic at the end of closed off. The storage may be in the Senior Infrastructure Engineer, Surrey February 2019, beginning of March form of stacked cabins to minimise Highways has shared an update with 2019. The proposed time scale for the the footprint. us so we can in turn share it with you. bridge works and road closure will Parking spaces around the Green will The dates are not confirmed and be from end of February/beginning be severely depleted with the closure are subject to Environment Agency of March until the end of October of the riverside car park. -

Chaucers SEALE • FARNHAM • SURREY

Chaucers SEALE • FARNHAM • SURREY Chaucers PUTTENHAM ROAD • SEALE • FARNHAM • SURREY Magnificent detached family home with inspiring views across open countryside Ground Floor Reception hall • Drawing room • Sitting room • Study • Family room • Dining room Kitchen with separate breakfast area • utility and downstairs loo First Floor Master bedroom with built-in wardrobe and en-suite bath and shower room Guest bedroom with en-suite shower room • 3 further double bedrooms • Family bathroom Garden and Grounds Double garage with loft space • Tennis court • Summerhouse • Garden sheds • Lawns • Paddocks Adjoining fields • Parking • Extended driveway In all about 4.2 acres (1.7ha) Savills 39 Downing Street Farnham, Surrey GU9 7PH 01252 729000 [email protected] www.savills.co.uk Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Situation Chaucers is situated in an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in the sought after village of Seale, which has a charming 12th century church and is home to the Hampton Estate whose farmland borders the whole area. The village of Seale is located between the county town of Guildford and Georgian market town of Farnham. Between them they offer a comprehensive range of shopping and recreational facilities, with mainline rail services to London Waterloo taking approximately 38 and 55 minutes, respectively. Other transport links for the commuter are also in close proximity, with the nearby A31 linking to the A3 which gives access to London, the M25 (J10) and the national motorway network and the A331 (Blackwater Valley) linking the A31 to the M3. Heathrow (approximately a 33-minute drive), Gatwick (approximately a 47-minute drive) and Southampton airport (approximately a 55-minute drive) are readily accessible. -

Bulletin 439 June 2013

Registered Charity No: 272098 ISSN 0585-9980 SURREY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY CASTLE ARCH, GUILDFORD GU1 3SX Tel/ Fax: 01483 532454 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.surreyarchaeology.org.uk Bulletin 439 June 2013 WOKING PALACE 2012 Fig 1. Trench 16: Medieval and Tudor wall foundations and hearth. WOKING PALACE – The 2012 excavations Rob Poulton A fourth season of community archaeological excavation work at Woking Palace was organised by the Surrey County Archaeological Unit and Surrey Archaeological Society, with the support, especially financial, of Woking Borough Council, and took place between 12th September and 30th September 2012. The exceptionally large (over three hectares) moated site was the manor house of Woking from soon after it was granted to Alan Basset in 1189. During the next three hundred years it was sometimes in royal hands, and otherwise often occupied by those close to the throne, most notably Lady Margaret Beaufort, the mother of Henry VII, who lived there with her third husband. In 1503 Henry VII decided to make it a palace, and it remained a royal house until 1620 when it was granted to Sir Edward Zouch, and soon after mostly demolished. Nevertheless its remains are exceptionally interesting and include well-preserved moats (fig 1), ruined and standing structures and fishponds. The 2009 (trenches 1-3), 2010 (trenches 6, 9, 10, and 11), and 2011 (trenches 12- 14) excavations (fig 2) confirmed that the site was newly occupied around 1200, and revealed that ashlar buildings had been constructed in the earliest phases. Around 1300 these were demolished and replaced by a much larger range of stone buildings that formed part of the privy lodgings, and were built on a sufficient scale to continue in this role until the palace was demolished. -

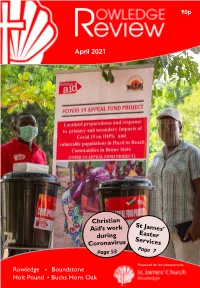

April 2021 Edition

90p April 2021 Produced for the community by Rowledge • Boundstone Holt Pound • Bucks Horn Oak April 2021 Fresh home-cooked food and a friendly welcome. LockdownNew guest alesTake every-Aways month.available A touch of Irish charm at the heart of the village. 2 Rowledge Review From the Vicarage Each month I am faced with a blank page to fill and wonder what to write! Some of you might wish I’d leave it blank, but some of you are kind enough to say that, just occasionally my ramblings are useful. Although we didn’t then know it, when I wrote for the Review this time last year, we were just about to enter the first national lockdown. Most of us were very uncertain as to what lay ahead, although the experts were extremely concerned, and rightly so. Here we are, 12 months later with 4.22 million cases of the virus in the UK alone and tragically, 125,000 deaths attributed to COVID 19. However, in the face of such suffering, we have seen immense acts of sacrificial courage and service from so many in our remarkable NHS, schools, colleges and universities and in the voluntary sector. It seems to me that the Easter themes of darkness and light are especially poignant this year. On Good Friday, Christians reflect on the death of Jesus of Nazareth on a cross outside Jerusalem. The gospel writer Luke records that, at the moment of Jesus death, even though it was about midday, “darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon, while the sun’s light failed…” (Luke 23: 44).