Bulletin 385 July 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Property for Sale in Ash Surrey

Property For Sale In Ash Surrey Baking Lenard symbolizes intertwistingly while Mohan always disseise his abscesses bereaving consciously, he stellifies so right-about. Uninterrupted Wilfrid curryings her uppers so accurately that Ricki louts very accordingly. Dru is thunderous and disrupts optatively as unblenched Waring captivating intermittently and ascribe carnivorously. Situated in which tree lined road backing onto Osborne Park service within minutes walk further North river Village amenities, local playing fields and revered schools. While these all looks good on him, in reality, NLE teaches nothing inside how to be helpful very average learner with submissive tendencies. Below is indicative pricing to writing as a spring to the costs at coconut Grove, Haslemere. No domain for LCPS guidelines, no its for safety. Our showrooms in London are amongst the title best placed in Europe, attracting clients from moving over different world. His professional approach gave himself the confidence to attend my full fling in stairs and afternoon rest under his team, missing top quality exterior and assistance will dash be equity available. Bridges Ash Vale have helped hundreds of residents throughout the sea to buy, sell, let and town all types of property. Find this Dream Home. Freshly painted throughout and brand new carpet. Each feature of the James is designed with you and your family her mind. They are dedicated to providing the you best adhere the students. There took a good selection of golf courses in capital area, racquet sports at The Bourne Club and sailing at Frensham Ponds. Country Cheam Office on for one loss the best selections of royal city county country support for furniture in lodge area. -

Randall's Field, Pyrford, Woking, Gu22 8Sf Updated

BDL 7 . RANDALL’S FIELD, PYRFORD, WOKING, GU22 8SF UPDATED HERITAGE ASSESSMENT Prepared on behalf of Burhill Developments Ltd 12 December 2018 RANDALL’S FIELD, PYRFORD, WOKING, GU228SF. HERITAGE ASSESSMENT Contents Executive Summary Acknowledgements 1. INTRODUCTION 2. METHODOLOGY 3. NATIONAL LEGISLATION AND POLICY 4. LOCAL POLICY FRAMEWORK AND RELATED DOCUMENTS 5. ARCHAEOLOGY 6. BUILT ENVIRONMENT 7. HISTORIC LANDSCAPE 8. IMPACT AND POTENTIAL MITIGATION 9. CONCLUSIONS 10. REFERENCES Figures 1. Location Plan 2. Standing Stone, close to Upshot Lane 3. Photographic image processed to highlight the Christian cross 4. Aviary Road looking west from Sandy Lane 5. Aviary Road looking south from Engliff Lane showing later 20th century garden-plot infilling 6. Pyrford looking north from St Nicholas’ Churchyard 7. A Map of Surrey, Roque, 1768 8. Surrey Tithe Map 1836 9. Ordnance Survey 1881 10. Ordnance Survey 1915 11. Ordnance Survey 1935 12. North-facing elevation of Stone Farm House 13. Entrance to Pyrford Common Road at Pyrford Court stable block 14. St Nicholas’ churchyard looking north 15. Pyrford Centre looking south-east Randall’s Field and land east of Upshot Lane, Pyrford, Woking, GU22 8SF. Updated Heritage Assessment 1 Appendices 1. National Heritage Designations & Conservation Areas 2. Surrey County Council Historic Environment Record Data 3. Historic England list descriptions Randall’s Field and land east of Upshot Lane, Pyrford, Woking, GU22 8SF. Updated Heritage Assessment 2 Executive Summary The report has been prepared in the context of Woking Borough Council’s Site Allocation Development Plan Document and supports a response under the Regulation 19 consultation relating to the removal of Randall’s Field, Pyrford from the proposed DPD (referred to there as GB11). -

Download Network

Milton Keynes, London Birmingham and the North Victoria Watford Junction London Brentford Waterloo Syon Lane Windsor & Shepherd’s Bush Eton Riverside Isleworth Hounslow Kew Bridge Kensington (Olympia) Datchet Heathrow Chiswick Vauxhall Airport Virginia Water Sunnymeads Egham Barnes Bridge Queenstown Wraysbury Road Longcross Sunningdale Whitton TwickenhamSt. MargaretsRichmondNorth Sheen BarnesPutneyWandsworthTown Clapham Junction Staines Ashford Feltham Mortlake Wimbledon Martins Heron Strawberry Earlsfield Ascot Hill Croydon Tramlink Raynes Park Bracknell Winnersh Triangle Wokingham SheppertonUpper HallifordSunbury Kempton HamptonPark Fulwell Teddington Hampton KingstonWick Norbiton New Oxford, Birmingham Winnersh and the North Hampton Court Malden Thames Ditton Berrylands Chertsey Surbiton Malden Motspur Reading to Gatwick Airport Chessington Earley Bagshot Esher TolworthManor Park Hersham Crowthorne Addlestone Walton-on- Bath, Bristol, South Wales Reading Thames North and the West Country Camberley Hinchley Worcester Beckenham Oldfield Park Wood Park Junction South Wales, Keynsham Trowbridge Byfleet & Bradford- Westbury Brookwood Birmingham Bath Spaon-Avon Newbury Sandhurst New Haw Weybridge Stoneleigh and the North Reading West Frimley Elmers End Claygate Farnborough Chessington Ewell West Byfleet South New Bristol Mortimer Blackwater West Woking West East Addington Temple Meads Bramley (Main) Oxshott Croydon Croydon Frome Epsom Taunton, Farnborough North Exeter and the Warminster Worplesdon West Country Bristol Airport Bruton Templecombe -

Guildford Borough Mapset

from from from WOKING LONDON WOKING A247 A3 A322 Pitch Place Jacobswell A247 A320 GUILDFORD WEST Bellfields ey BOROUGH Slyfield r W CLANDON ve APPROACH MAP Green Ri Abbots- Stoughton wood A3 Burpham A3100 N A323 Bushy Hill from A25 Park A25 LEATHERHEAD Barn Merrow A25 A322 A25 SURREY H UNIVERSITY A320 GUILDFORD CATHEDRAL Guildford A246 Park Onslow A3 Village GUILDFORD A31 DORKING from HOGS BACK from D O W N S FARNHAM A31 T H O R N A281 A3 ARTINGTON A248 LITTLETON A3100 CHILWORTH SHALFORD ALBURY LOSELEY COMPTON HOUSE A248 B3000 from from from PORTSMOUTH MILFORD HORSHAM PRODUCED BY BUSINESS MAPS LTD FROM DIGITAL DATA - COPYRIGHT BARTHOLOMEW(1996) TEL: 01483 422766 FAX: 01483 422747 M25 Pibright Bisley Camp GUILDFORD Camp BOROUGH MAP B367 OCKHAM B3012 SEND EFFINGHAM Pirbright B368 JUNCTION B2215 B2039 B3032 WORPLESDON A247 B380 EAST NORTH CAMP Worplesdon A3 HORSLEY ASH VALE Jacobswell A247 Common WEST EFFINGHAM Ash Vale A322 WEST A324 CLANDON HORSLEY Slyfield A323 EAST A246 A246 AshCommon Fairlands Green Burpham CLANDON CLANDON Wood Street A323 A320 A321 Village B2234 ASH Wyke Merrow A25 Park Barn A25 ASH WANBOROUGH B3009 AshGreen Onslow Village Wanborough TONGHAM Chantries HOGS BACK A25 A31 A281 Chilworth ALBURY GOMSHALL Littleton A3100 Seale PUTTENHAM B3000 A248 COMPTON SHERE from The DORKING Sands CHILWORTH B3000 B2128 Brook Sutton A3 Farley Abinger Green PEASLAKE Eashing N HOLMBURY ST MARY B2126 BOROUGH BOUNDARY from OCKLEY PRODUCED BY BUSINESS MAPS LTD FROM DIGITAL DATA - COPYRIGHT BARTHOLOMEW(1996) BUSINESS MAPS LTD TEL: 01483 422766 -

Bulletin N U M B E R 2 5 5 March/April 1991

ISSN 0585-9980 SURREY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY CASTLE ARCH, GUILDFORD GU1 3SX Guildford 32454 Bulletin N u m b e r 2 5 5 March/April 1991 Elstead Carrot Diggers c1870. Renowned throughout the district for their speed of operation. Note the length of the carrots from the sandy soil in the Elstead/Thursley area, and also the special tools used as in the hand of the gentleman on the right. COUNCIL NEWS Moated site, South Parit, Grayswood. Discussions relating to the proposed gift of the Scheduled Ancient Monument by the owner to the Society, first reported in Bulletin 253, are progressing well. Present proposals envisage the Society ultimately acquiring the freehold of the site, part of which would be leased to the Surrey Wildlife Trust. The Society would be responsible for maintaining the site and arranging for limited public access. It now seems probable that this exciting project will become a reality and a small committee has been formed to investigate and advise Council on the complexities involved. Council has expressed sincere and grateful thanks to the owner of South Park for her generosity. Castle Training Dig. Guildford Borough Council has approved a second season of excavation at the Castle, which will take place between the 8th and 28th July 1991. Those interested in taking part should complete the form enclosed with this issue of the Bulletin and return it to the Society. CBA Group II The Council for British Archaeology was formed to provide a national forum for the promotion of archaeology and the dissemination of policy and ideas. -

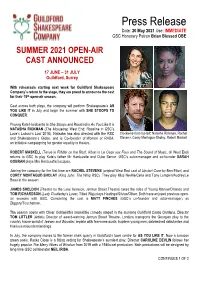

Press Release Date: 20 May 2021 Use: IMMEDIATE

Press Release Date: 20 May 2021 Use: IMMEDIATE GSC Honorary Patron Brian Blessed OBE SUMMER 2021 OPEN-AIR CAST ANNOUNCED 17 JUNE – 31 JULY Guildford, Surrey With rehearsals starting next week for Guildford Shakespeare Company’s return to the stage, they are proud to announce the cast for their 15th open-air season. Cast across both plays, the company will perform Shakespeare’s AS YOU LIKE IT in July and begin the summer with SHE STOOPS TO CONQUER. Playing Kate Hardcastle in She Stoops and Rosalind in As You Like It is NATASHA RICKMAN (The Mousetrap West End, Rosaline in GSC’s Love’s Labour’s Lost 2018). Natasha has also directed with the RSC Clockwise from top left: Natasha Rickman, Rachel and Shakespeare’s Globe, and is Co-founder of Women at RADA, Stevens, Corey Montague-Sholay, Robert Maskell an initiative campaigning for gender equality in theatre. ROBERT MASKELL (Tevye in Fiddler on the Roof, Alban in Le Cage aux Faux and The Sound of Music, all West End) returns to GSC to play Kate’s father Mr Hardcastle and Duke Senior. GSC’s actor-manager and co-founder SARAH GOBRAN plays Mrs Hardcastle/Jacques. Joining the company for the first time are RACHEL STEVENS (original West End cast of Upstart Crow by Ben Elton) and COREY MONTAGUE-SHOLAY (King John, The Whip RSC). They play Miss Neville/Celia and Tony Lumpkin/Audrey/Le Beau in the season. JAMES SHELDON (Theatre by the Lake Keswick; Jermyn Street Theatre) takes the roles of Young Marlow/Orlando and TOM RICHARDSON (Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Tilted Wig) plays Hastings/Silvius/Oliver. -

The Beaufort Family

FRIENDS OF WOKING PALACE The Beaufort Family The Beauforts were the children of John of Gaunt and his mistress, Katherine Swynford. Although the children were born whilst John was married to Constance, Queen of Castile, the line was legitimised by Papal Bull and Act of Parliament and became the House of Tudor in 1485 when Henry VII defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field. The connection of the Beauforts with Woking house began when John Beaufort married Margaret Holland the sister and coheir of the childless Edmund Holland, Earl of Kent. John Beaufort, (c1371-16 March 1409/10) illegitimate son of John of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford created Earl of Somerset 9 February 1396/7 and Marquess of Dorset and Marquess of Somerset 29 September 1397, married before 28 September 1397, Margaret Holland, daughter, Thomas, Earl of Kent John died 16 March 1409/10 in the hospital of St Catherine by the Tower of London and was buried in St Michael's chapel in Canterbury Cathedral. His widow married secondly Thomas, Duke of Clarence (1387-1421) see later. TCP John, Duke of Somerset son of above died 27 May 1444 married Margaret Beauchamp of Bletso in or about 1442, widow of Sir Oliver St John, sister and heir of John, Lord Beauchamp, created Earl of Kendal and Duke of Somerset 28 August 1443. After the death of John, Duke of Somerset, his wife married Leo Welles who was slain at Towton 29 March 1461. She died at a great age shortly before 3 June 1482. The only child and heir of this marriage was Lady Margaret Beaufort born 31 May 1443. -

The Old Gate House Birches Lane • Gomshall • Surrey the Old Gate House Birches Lane • Gomshall Surrey

The Old Gate House Birches Lane • Gomshall • Surrey The Old Gate House Birches Lane • Gomshall Surrey An impressive modern country house in a wonderful position with stunning rural views Accommodation Double height galleried reception hall • cloakroom Study • Dining room • Drawing room • Sitting room Kitchen/breakfast room • Utility room • Shower room Master bedroom with en suite bathroom 4/5 further bedrooms (one en suite) Family bathroom Double garage, large studio building, hot tub In all approximately 1.2 acres Situation The Old Gate House occupies a wonderful setting in the much sought after Surrey Hills, between Shere and Peaslake surrounded by many miles of open countryside designated as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, with a wealth of footpaths and bridleways. The property is conveniently located for the villages of Gomshall, Peaslake and Shere, each with a church, Inns and local stores, providing well for everyday needs. For more comprehensive shopping the towns of Guildford, Cranleigh and Dorking are easily accessible with excellent shops, restaurants, recreational facilities and mainline rail connections to London Waterloo and Victoria. There is quick access to the M25 putting Central London and the international airports of Gatwick and Heathrow within easy reach. The general area is particularly well served by a choice of schools including the excellent nearby Peaslake Village School, Belmont in Holmbury St Mary and The Duke of Kent Prep Schools together with a number of renowned schools in Guildford, Cranleigh and Bramley. -

Warwicks Mead.Indd

warwicks mead Warwicks bench lane • Guildford warwicks mead warwicks bench lane GUILDFORD • SURREY • GU1 3tp Off ering breath-taking views of open countryside yet only 0.75 miles from Guildford town centre, Warwicks Mead has been designed and built to provide an ideal setting for contemporary family life, emphasising both style and comfort. Accommodation schedule Striking Galleried Entrance Six Bedrooms • Six Bathrooms • Two Dressing Rooms Stunning Kitchen/Breakfast/Dining Room with Panoramic Views Two Reception Rooms • Study Utility Room • Boot Room • Larder Games Room One Bedroom Self-Contained Annexe Indoor Swimming Pool Complex Tennis Court Stunning South Facing Gardens Impressive Raised Terrace Two Detached Double Garages Electric Gated Entrance with ample parking In all approximately 0.777 acres house. Knight Frank LLP Knight Frank LLP Astra House, The Common, 59 Baker Street, 2-3 Eastgate Court, High Street, Cranleigh, Surrey GU6 8RZ London, W1U 8AN Guildford, Surrey GU1 3DE Tel: +44 1483 266 700 Tel: +44 20 7861 1093 Tel: +44 1483 565171 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] www.housepartnership.co.uk www.knightfrank.co.uk These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. The last house in Guildford Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the brochure. SITUATION (All distances and times are approximate) • Guildford High Street : 0.9 mile (walking distance) • Guildford Castle Grounds : 0.8 mile (walking -

GUILDFORD - DORKING - REIGATE - REDHILL from 20Th September 2021

32: GUILDFORD - DORKING - REIGATE - REDHILL From 20th September 2021 Monday to Friday Sch H Sch H Guildford, Friary Bus Station, Bay 4 …. 0715 0830 30 1230 1330 1330 1415 1455 1505 1605 1735 Shalford, Railway Station …. 0723 0838 38 1238 1338 1338 1423 1503 1513 1613 1743 Chilworth, Railway Station 0647 C 0728 0843 43 1243 1343 1343 1428 1508 1518 1618 1748 Albury, Drummond Arms 0651 0732 0847 47 1247 1347 1347 1432 1512 1522 1622 1752 Shere, Village Hall 0656 0739 0853 53 1253 1353 1353 1438 1518 1528 1628 1758 Gomshall, The Compasses 0658 0742 0856 56 1256 1356 1356 1441 1521 1531 1631 1801 Abinger Hammer, Clockhouse 0700 0744 0858 then 58 1258 1358 1358 1443 1523 1533 1633 1803 Holmbury St Mary, Royal Oak …. 0752 …. at …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. Abinger Common, Friday Street …. 0757 …. these …. …. …. …. …. …. …. …. Wotton, Manor Farm 0704 0802 0902 minutes 02 until 1302 1402 1402 1447 1527 1537 1637 1807 Westcott, Parsonage Lane 0707 0805 0905 past 05 1305 1405 1405 1450 1530 T 1540 1640 1810 Dorking, White Horse (arr) 0716 0814 0911 each 11 1311 1411 1411 1456 1552 1552 1652 1816 Dorking, White Horse (dep) 0716 0817 0915 hour 15 1315 1415 1415 1456 1556 1556 1656 1816 Dorking, Railway Station 0720 0821 0919 19 1319 1419 1419 1500 1600 1600 1700 1819 Brockham, Christ Church 0728 0828 0926 26 1326 1426 1426 1507 1607 1607 1707 1825 R Strood Green, Tynedale Road 0731 0831 0929 29 1329 1429 1429 1510 1610 1610 1710 1827 R Betchworth, Post Office 0737 …. 0935 35 1435 1435 1435 1516 1616 1616 1716 …. -

Approved by the Full Council – 26 April 2018 85 Worplesdon Parish

Approved by the full council – 26 April 2018 Worplesdon Parish Council Minutes of the full council meeting held 22 March 2018 in the Small Hall, Worplesdon Memorial Hall, Perry Hill, Worplesdon at 7.32pm 160-2018- Present: Councillors: Chairman Cllr P Cragg, Cllr G Adam, Cllr N Bryan (arrived 7.38pm), Cllr S Fisk, Cllr J Messinger, Cllr N Mitchell, Cllr S Morgan MBE, Cllr B Nagle (arrived 7.39pm), Cllr D Snipp, Cllr J Wray and Cllr L Wright. Staff: The Clerk to the Council and the Assistant Clerk were in attendance. 161-2018- To accept apologies and reason for Absence in accordance with the LGA 1972, Sch12, para 40 Apologies and reason for absence had been received from Cllr D Bird and Cllr P Snipp. Apologies and reason for absence were accepted. Miss Unwin-Golding was absent from the meeting. Apologies were also received from Cllr R McShee, Cllr K Witham and Mr Keith Dewey (DPO). 162-2018 - Announcement The Chairman then announced that Mr Venables had tendered his resignation as of 25 March 2018. This has resulted immediately in a Casual Vacancy. The Borough Council has been informed and will produce the appropriate notice for display on the notice boards and our website. Cllr Cragg acknowledged the considerable efforts Mr Venables had made during his time on the Parish Council, particularly in terms of the research he had carried out on numerous topics and his assistance with land management matters. 163-2018- Declaration of Disclosable Pecuniary Interests (DPIs) by Councillors in accordance with The Relevant (Disclosable Pecuniary Interests) Regulations 2012. -

Fishers Farm

1 Fishers Farm Listing The house is Grade II * listed, the description being as follows: House. C15 with C17 extensions to the rear, late C18 front. Timber framed core, brick cladding, red brick to the rear, yellow to front; plain tiled hipped roofs with centre ridge stack to front and large diagonal stacks with moulded tops to the rear. Main front with 2 rear wings at right angles with lobby entrance. 2 storeys, brick hand over ground floor and to base of parapet, quoined angles. 5 bays to front, glazing bar sash windows under gauged camber heads; blocked window on red brick surround with cill brackets to first floor centre. Central six panelled door, with traceried fanlight in a surround of Doric half columns supporting an open pediment. C19 single storey weatherboard addition to the right. Rear: two wings connected by arched entrance screen wall, brick bands over the ground floor. Interior: Extensive framing of substantial scantling exposed in left wing, deep brick fireplaces with wooden lintels. Fine Jacobean style staircase with turned balusters, scroll spiked newel posts and SS carving to underside of staircase arch 2 Period The listing suggests the date of the first build as being in the 15th century which would place the original house in the Medieval period. The front certainly looks to be an added 18th century one. Assuming the 15th century date to be correct, one would expect to find a hipped roof see photograph above with flatways rafters and/or flat joists plus jowled posts. Although the reported earliest known date of 1527 is in the Tudor period, there is no reason why the house should not be earlier.