Chapter Five Considering Linguistic Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catching Words in a Stream of Speech

Catching Words in a Stream of Speech: Computational Simulations of Segmenting Transcribed Child-Directed Speech Çagrı˘ Çöltekin CLCG The work presented here was carried out under the auspices of the School of Behavioural and Cognitive Neuroscience and the Center for Language and Cognition Groningen of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Groningen. Groningen Dissertations in Linguistics 97 ISSN 0928-0030 2011, Çagrı˘ Çöltekin This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Cover art, titled auto, by Franek Timur Çöltekin Document prepared with LATEX 2" and typeset by pdfTEX Printed by Wöhrmann Print Service, Zutphen RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT GRONINGEN Catching Words in a Stream of Speech Computational Simulations of Segmenting Transcribed Child-Directed Speech Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Letteren aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, dr. E. Sterken, in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 8 december 2011 om 14.30 uur door Çagrı˘ Çöltekin geboren op 28 februari 1972 Çıldır, Turkije Promotor: Prof. dr. ir. J. Nerbonne Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. dr. A. van den Bosch Prof. dr. P. Hendriks Prof. dr. P. Monaghan ISBN (electronic version): 978-90-367-5259-6 ISBN (print version): 978-90-367-5232-9 Preface I started my PhD project with a more ambitious goal than what might have been achieved in this dissertation. I wanted to touch most issues of language acquisition, developing computational models for a wider range of phenomena. -

Seizure Frequency

Smith, Niall (2013) The everyday social geographies of living with epilepsy. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4696/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] THE EVERYDAY SOCIAL GEOGRAPHIES OF LIVING WITH EPILEPSY NIALL D. SMITH THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SCHOOL OF GEOGRAPHICAL AND EARTH SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW JUNE 2013 ABSTRACT Radical, ‘eventful’ bodily vulnerability has yet to receive sustained attention in contemporary human geography. As one way of addressing the implications of existential vulnerability, this thesis explores the social geographies of people living with epilepsy. It draws upon multiple- methods research comprising an extensive mixed-methods questionnaire and semi-structured interviews, all conducted with people with epilepsy who are members of the charity, Epilepsy Scotland, the project partner. By paying attention to the (post-)phenomenological experience of ‘seizures’, the thesis argues that a failure to appreciate the complex and often extremely troubling spatialities of epileptic episodes invariably results in sustaining the stigmatisation of epilepsy and the partial views of ‘outsiders’. -

![Downloaded by [New York University] at 06:54 14 August 2016 Classic Case Studies in Psychology](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8368/downloaded-by-new-york-university-at-06-54-14-august-2016-classic-case-studies-in-psychology-738368.webp)

Downloaded by [New York University] at 06:54 14 August 2016 Classic Case Studies in Psychology

Downloaded by [New York University] at 06:54 14 August 2016 Classic Case Studies in Psychology The human mind is both extraordinary and compelling. But this is more than a collection of case studies; it is a selection of stories that illustrate some of the most extreme forms of human behaviour. From the leader who convinced his followers to kill themselves to the man who lost his memory; from the boy who was brought up as a girl to the woman with several personalities, Geoff Rolls illustrates some of the most fundamental tenets of psychology. Each case study has provided invaluable insights for scholars and researchers, and amazed the public at large. Several have been the inspiration for works of fiction, for example the story of Kim Peek, the real Rain Man. This new edition features three new case studies, including the story of Charles Decker who was tried for the attempted murder of two people but acquitted on the basis of a neurological condition, and Dorothy Martin, whose persisting belief in an impending alien invasion is an illuminating example of cognitive dissonance. In addition, each case study is contextualized with more typical behaviour, while the latest thinking in each sub-field is also discussed. Classic Case Studies in Psychology is accessibly written and requires no prior knowledge of psychology, but simply an interest in the human condition. It is a book that will amaze, sometimes disturb, but above all enlighten its readers. Downloaded by [New York University] at 06:54 14 August 2016 Geoff Rolls is Head of Psychology at Peter Symonds College in Winchester and formerly a Research Fellow at Southampton University, UK. -

The Archidoxes of Magic, 2010, Theophrastus Paracelsus, 1163581216, 9781163581216, Kessinger Publishing, 2010

The Archidoxes of Magic, 2010, Theophrastus Paracelsus, 1163581216, 9781163581216, Kessinger Publishing, 2010 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1x1etg0 http://goo.gl/RN6Tr http://www.powells.com/s?kw=The+Archidoxes+of+Magic Of the Supreme Mysteries of Nature; of the Spirits of Planets; Secrets of Alchemy; Occult Philosophy; Signs of the Zodiack, Magical Cure of Diseases; and Celestial Medicines; Partial Contents: Of Simple Fire; Multiplicity of Fire; The Metals of the Planets; Spirit of the Sun; Moon, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn; Of Tinctures how they are made; Conjunction of Male and Female; To make the Furnace; To place the Fire; The Red Colour; Of Consecrations; Of Ceremonies Magical; Of Conjurations; Supernatural Diseases must have Supernatural Cures; Visions and Dreams; Dreams natural and Supernatural; Of Imagination; Of Hidden Treasure; The Abuse of Magick; Preservatives against Witchcraft; Manner of helping persons bewitched; Of the mystery of the twelve Signs; Celestial Medicines. DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1jMAVSQ http://avaxsearch.com/?q=The+Archidoxes+of+Magic http://bit.ly/1lmpSnE , , , , . The Strangest Animals in the World , S. Talalaj, May 1, 1994, Animals, 221 pages. Describes the habits and characteristics of many peculiar animals. Also outlines mysteries and myths associated with certain animals such as crocodiles, rats and baboonsBetter How Jesus Satisfies the Search for Meaning, Tim Chaddick, Craig Borlase, Sep 1, 2013, Religion, 240 pages. “What does it take to find satisfaction? Will I ever find something in life that’s better than this?” Most people live a life they never would have planned. The good news is The 'Language Instinct' Debate Revised Edition, Geoffrey Sampson, Apr 1, 2005, Language Arts & Disciplines, 224 pages. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Looking Back, Seeing the Clubhouse in Transformative Terms

(Presented in June 2005 in Helsinki Finland at the 13th annual International Seminar on the Clubhouse Model) Plenary speech on “The Clubhouse Journey to Recovery” By Mark Glickman When Robby asked me to make this speech my first impulse, which is unfortunately usually my first impulse, was to say no. But Robby. knowing this, said would I please do it. If at least for old times sake. So I said yes. And that reminds me how all things at the clubhouse flow from relationships. But I’m getting ahead of myself. My story starts a long time ago. Thirty two years ago I walked down 47th street for the first time to the door of fountain house. By my side was my father, who was about the same age as I am now, 58. My dad died a few years ago of Alzheimer’s. If he hadn’t been there that day, long ago, I would either have never gone, or run out the front door of Fountain House shortly after arriving.. When I entered Fountain House for the first time it looked as strange a world to me, as when Dorothy opened the door after crash landing in her tornado driven house in the movie “The Wizard of Oz”. I was in a state of shock. What I thought was going to be a great life had been rudely interrupted at the age of 24. The print was barely dry on my college diploma and rather than entering the promised land of a job in broadcasting or film, I had just left a mental hospital after a two month stay. -

SAVING LITERACY SAVING Dr

SAVING LITERACY Dr. Susan Rich Sheridan is a scholar/teacher with degrees in English, Art and Education. Her Neuroconstructive, brain-based theory and marks- based practice of literacy have a twenty-year history, including teaching first grade through college. Saving Literacy introduces the Scribbling/Drawing/ Writing program for children 10 months to 6 years, including developmental SAVING LITERACY benchmarks, lesson plans, evaluation tools, and research questions designed for professional caregivers: preschool and daycare providers, elementary school teachers, child psychologists, art teachers and art therapists, speech How Marks Change pathologists and researchers in child development and education. The goals of the program are sustained attention, emotional control and connection, expanded speech and literacy. Autism and the effects of technology are Minds discussed. Dr. Sheridan has published a companion book for parents, HandMade Marks. Attention “What we most need now… is a fresh perspective on the masses of data that neurobiologists have gathered, and on the puzzles those data pose… How do brains make sense of the world (?)… (A) new general theory… requires new assumptions and new definitions. I believe that the idea of meaning, a critical concept that defines the relations of each brain to the world, is central to current debates in philosophy and cognitive science, and will Connection become so in neurobiology… Doodling can and should accompany if not even precede speaking. Language derives from the dynamics and structure of intentional behavior... and the face and hand areas of the cortex lie side by side, undergoing the same patterns of neural development. They are inextricably linked, as we know from the necessity of Literacy moving our hands and fingers as we speak to communicate meaning most effectively.” Correspondence between Dr. -

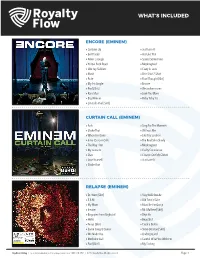

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. -

THE ARACHNIDS of RICHMOND by John Poulakos ACT 1 <Music>

THE ARACHNIDS OF RICHMOND By John Poulakos ACT 1 <Music> Spiderman: What is it that I see? Why, it’s my favorite messenger! Come, you endless source of the new and the unanticipated. Tell me. What’s the word? Messenger: How are you Boss? So very nice to see you. Here, I brought you some string beans. S: Let us dispense with the typical formalities. Cut to the chase and give me the news. M: You see, Boss. I mean. You know. The thing is that . S: You are hesitating. You are hesitating. What is the deal? M: Oh yes, the deal. The deal is like. I mean. For example. I am like. You know. It’s just not fair. You know? S: You make no sense. You are talking but you are not saying anything. What is the message? Spit it out. M: I hope that . I hope that. Like, you won’t be like angry at me or anything. S: Why should I be angry at you? M: Be. be. because. Well. I’ll tell you. The news is not good. S: Give it to me straight. I can take it. M: Well, here it is. Zeus, the almighty ruler of gods and mortals, the guardian of broccoli and string beans, the protector of video games, joy sticks and widows, is angry. S: What is he angry about? M: Humans everywhere are replacing their faith in him with their faculty of reason. S: I don’t get it. Isn’t he the one who endowed them with reason? M: I am not here to reason with you. -

SCHOOL of EDUCATION, HEALTH and SCIENCE a Thesis Submitted

SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, HEALTH AND SCIENCE PROGRAMME CODE: PX3AA PROGRAMME TITLE: DOCTOR of EDUCATION (EdD) MODULE CODE: 8EU007 MODULE TITLE: Work Based Project (Independent Phase) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education (EdD) award of the University of Derby . A case study of a school in Zimbabwe: Investigating challenges faced by rural O-level students and strategies used by teachers in the English Reading- comprehension classes. By: MAXWELL OBEDIAH GUNDUZA KANYOKA: B.Phil. M.Ed. ID NUMBER: 100087076 May: 2018 i Sensitivity: Internal ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My Director of studies, the late Dr Michael Flay, for his positive advice and never- ending constructive support in guiding me through the different stages of the research, and for his perceptive advice from whom I have learnt so much that will assist my own- going career; Then after his death his replacement, my programme co-ordinator Dr Neil Radford and first supervisor for his support and advice, my second supervisor Dr Codra Spencer for her unending zeal to help me include whatever she thought useful, advised and suggested as important to be included in the study; and my friend’s Dr Washington Karumazondo, Dr Kordwick Ndebele and Mr Onisimo Takaingofa for their unwavering support; The Ministry of Education Sport and Culture in Zimbabwe, which accommodated my study in one secondary school in Zimbabwe; The headmaster of the school where I carried out this study, the HoD and the department of English personnel who generously cooperated -

ALTERNATIVE (RE)VIEWS the Language Myth

ALTERNATIVE (RE)VIEWS Editors’ note: We invited six commentaries on Vyvyan Evans’s book The language myth from scholars with differing perspectives. The reviewers were free to choose what they focused on; that is, they were not asked to provide a complete review of the contents of the book. The reviews are listed in alphabetical order by the names of the authors. [Gregory N. Carlson and Helen Goodluck] The language myth: Why language is not an instinct. By V yvyan Evans. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014. Pp. xi, 304. ISBN 9781107619753. $29.99. Beyond caricatures: Commentary on Evans 2014 Farrell Ackerman Robert Malouf University of California, San Diego San Diego State University ‘In order to understand what another person is saying you must assume it is true, and try to imagine what it might be true of.’—George Miller, quoted by Ross (1982:8) As will be familiar to a Language audience, many of the central questions of language study were identified by luminaries of language—Wilhelm von Humboldt, Hermann Paul, Ferdinand de Saussure, Mikołaj Kruszewski, William Dwight Whitney, Edward Sapir, Leonard Bloomfield, John R. Firth, Roman Jakobson, and Charles Hockett, among others—who preceded both main - stream generative grammar (MGG) and modern cognitive/functional approaches. 1 These earlier generations of linguists were both awed and challenged by the intriguing properties of human languages. How can they be understood as biological, physiological, cognitive, and/or social ob - jects? What is the relation between the synchronic -

True Stories of Childhood Misfortune and Meaningless Sex

TANGERINE VAGINA : TRUE STORIES OF CHILDHOOD MISFORTUNE AND MEANINGLESS SEX Author: Anjum Choudhury Number of Pages: 84 pages Published Date: 30 Jul 2020 Publisher: Bowker Identifier Services Publication Country: none Language: English ISBN: 9780578718156 DOWNLOAD: TANGERINE VAGINA : TRUE STORIES OF CHILDHOOD MISFORTUNE AND MEANINGLESS SEX Tangerine Vagina : True Stories of Childhood Misfortune and Meaningless Sex PDF Book It studies each of the 26 movements, breathing exercises and rest poses that form the basis of every Bikram yoga class. Inspired by traditional Chinese medicine, Glow outlines simple, classic diagnostic techniques and therapies, a whole food diet, and active lifestyle to realize balance and tranquilitythe keys to true beautyand undo what time and stress have done. Vespasian had started the construction of the Colosseum shortly after becoming emperor in 69 A. " As strange as it sounds, maggot therapy is often a patient's last chance to prevent amputation of a limb. Henty to the humble cigarette card. Directions and the exercises themselves are given in Spanish. The inclusion of a new classification on Chinese medicinal herbs is particularly innovative, offering information that appears here for the first time in English. A total of 128 sample flashcards that allow you to study on the go. Contextualising Narrative Inquiry: Developing methodological approaches for local contextsNarrative inquiry is growing in popularity as a research methodology in the social sciences, medicine and the humanities. Debt-Free Spending Plan"The only how-to guide to today's most lucrative, fast-moving investment opportunity. Bruce Hammond shows how discounts and deals can reduce the "sicker price" at top colleges nationwide--even for families who would not have qualified for need-based aid in the past.