Dark Canadee…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seizure Frequency

Smith, Niall (2013) The everyday social geographies of living with epilepsy. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4696/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] THE EVERYDAY SOCIAL GEOGRAPHIES OF LIVING WITH EPILEPSY NIALL D. SMITH THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SCHOOL OF GEOGRAPHICAL AND EARTH SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW JUNE 2013 ABSTRACT Radical, ‘eventful’ bodily vulnerability has yet to receive sustained attention in contemporary human geography. As one way of addressing the implications of existential vulnerability, this thesis explores the social geographies of people living with epilepsy. It draws upon multiple- methods research comprising an extensive mixed-methods questionnaire and semi-structured interviews, all conducted with people with epilepsy who are members of the charity, Epilepsy Scotland, the project partner. By paying attention to the (post-)phenomenological experience of ‘seizures’, the thesis argues that a failure to appreciate the complex and often extremely troubling spatialities of epileptic episodes invariably results in sustaining the stigmatisation of epilepsy and the partial views of ‘outsiders’. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Looking Back, Seeing the Clubhouse in Transformative Terms

(Presented in June 2005 in Helsinki Finland at the 13th annual International Seminar on the Clubhouse Model) Plenary speech on “The Clubhouse Journey to Recovery” By Mark Glickman When Robby asked me to make this speech my first impulse, which is unfortunately usually my first impulse, was to say no. But Robby. knowing this, said would I please do it. If at least for old times sake. So I said yes. And that reminds me how all things at the clubhouse flow from relationships. But I’m getting ahead of myself. My story starts a long time ago. Thirty two years ago I walked down 47th street for the first time to the door of fountain house. By my side was my father, who was about the same age as I am now, 58. My dad died a few years ago of Alzheimer’s. If he hadn’t been there that day, long ago, I would either have never gone, or run out the front door of Fountain House shortly after arriving.. When I entered Fountain House for the first time it looked as strange a world to me, as when Dorothy opened the door after crash landing in her tornado driven house in the movie “The Wizard of Oz”. I was in a state of shock. What I thought was going to be a great life had been rudely interrupted at the age of 24. The print was barely dry on my college diploma and rather than entering the promised land of a job in broadcasting or film, I had just left a mental hospital after a two month stay. -

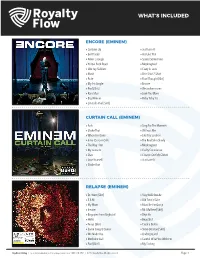

What's Included

WHAT’S INCLUDED ENCORE (EMINEM) » Curtains Up » Just Lose It » Evil Deeds » Ass Like That » Never Enough » Spend Some Time » Yellow Brick Road » Mockingbird » Like Toy Soldiers » Crazy in Love » Mosh » One Shot 2 Shot » Puke » Final Thought [Skit] » My 1st Single » Encore » Paul [Skit] » We as Americans » Rain Man » Love You More » Big Weenie » Ricky Ticky Toc » Em Calls Paul [Skit] CURTAIN CALL (EMINEM) » Fack » Sing For The Moment » Shake That » Without Me » When I’m Gone » Like Toy Soldiers » Intro (Curtain Call) » The Real Slim Shady » The Way I Am » Mockingbird » My name Is » Guilty Conscience » Stan » Cleanin Out My Closet » Lose Yourself » Just Lose It » Shake That RELAPSE (EMINEM) » Dr. West [Skit] » Stay Wide Awake » 3 A.M. » Old Time’s Sake » My Mom » Must Be the Ganja » Insane » Mr. Mathers [Skit] » Bagpipes from Baghdad » Déjà Vu » Hello » Beautiful » Tonya [Skit] » Crack a Bottle » Same Song & Dance » Steve Berman [Skit] » We Made You » Underground » Medicine Ball » Careful What You Wish For » Paul [Skit] » My Darling Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. All rights reserved. Page. 1 WHAT’S INCLUDED RELAPSE: REFILL (EMINEM) » Forever » Hell Breaks Loose » Buffalo Bill » Elevator » Taking My Ball » Music Box » Drop the Bomb On ‘Em RECOVERY (EMINEM) » Cold Wind Blows » Space Bound » Talkin’ 2 Myself » Cinderella Man » On Fire » 25 to Life » Won’t Back Down » So Bad » W.T.P. » Almost Famous » Going Through Changes » Love the Way You Lie » Not Afraid » You’re Never Over » Seduction » [Untitled Hidden Track] » No Love THE MARSHALL MATHERS LP 2 (EMINEM) » Bad Guy » Rap God » Parking Lot (Skit) » Brainless » Rhyme Or Reason » Stronger Than I Was » So Much Better » The Monster » Survival » So Far » Legacy » Love Game » Asshole » Headlights » Berzerk » Evil Twin Royalties Catalog | For more information on this catalog, contact us at 1-800-718-2891 | ©2017 Royalty Flow. -

THE ARACHNIDS of RICHMOND by John Poulakos ACT 1 <Music>

THE ARACHNIDS OF RICHMOND By John Poulakos ACT 1 <Music> Spiderman: What is it that I see? Why, it’s my favorite messenger! Come, you endless source of the new and the unanticipated. Tell me. What’s the word? Messenger: How are you Boss? So very nice to see you. Here, I brought you some string beans. S: Let us dispense with the typical formalities. Cut to the chase and give me the news. M: You see, Boss. I mean. You know. The thing is that . S: You are hesitating. You are hesitating. What is the deal? M: Oh yes, the deal. The deal is like. I mean. For example. I am like. You know. It’s just not fair. You know? S: You make no sense. You are talking but you are not saying anything. What is the message? Spit it out. M: I hope that . I hope that. Like, you won’t be like angry at me or anything. S: Why should I be angry at you? M: Be. be. because. Well. I’ll tell you. The news is not good. S: Give it to me straight. I can take it. M: Well, here it is. Zeus, the almighty ruler of gods and mortals, the guardian of broccoli and string beans, the protector of video games, joy sticks and widows, is angry. S: What is he angry about? M: Humans everywhere are replacing their faith in him with their faculty of reason. S: I don’t get it. Isn’t he the one who endowed them with reason? M: I am not here to reason with you. -

Chapter Five Considering Linguistic Knowledge

Chapter Five Chapter Five Considering Linguistic Knowledge At the end of the previous chapter, we noted that there may be principles underlying the acquisition of the lexicon that are not obvious at first glance. But isn’t that always the case in science? Who would have thought at the beginning of this century that general principles of physics govern the very way that all materials, living or otherwise, are constructed, or that principles of neurobiology control the very makeup of all living matter? From that perspective, it is perhaps not surprising that some rather non-obvious principles govern something as ubiquitous as the human’s implicit knowledge of language. This chapter is a pause of sorts from our usual head-long rush into technical detail, for here we cover some basic concepts and a few insights from language acquisition. These are important— indeed, have been important all along (except that we didn’t have time to bring them up)— because, as we shall see, for some linguists, they guide the very nature of linguistic theorizing, the general purpose of which is to ascertain what one’s implicit knowledge of language looks like in the first place. 1. Basic Concepts 1.1 Implicit knowledge of language All along in the course, we’ve been making reference to the native speaker’s knowledge, where with “native speaker” we mean any native speaker, not just one who happens to have had a lot of schooling, or one who can even read and write. But let’s be more precise now. When we speak of the native speaker’s implicit knowledge of language, we refer in linguistics to knowledge that many speakers may not even be aware of at all (hence implicit). -

Apr 02, 1976, Vol. 05 No. 06

Page 3 KALENDAR April 2, l<»76 KALENDAR PUBLICATIONS, INC. Box 6S7 San Francisco, Ca. 94101 _______________________ ^ 6 - 0 6 5 6 VOLUME FIVE Issue 06, April 2, W76 NEXT ISSUE FRIDAY DEADLINE Mo n d a y seem to have a bounce in their step breakfast. Then all Hell breaks loose and a fixed smile as though everything until 4:00 when a lovely buffet «rill be is Just alright. And there’s nothing spread out for all to enjoy. The party wrong with being on that kind of high. lasts all day and nite long with some special surprises thrown in Just to keep THOUGHTS AT RANDOM: you hard and happy, So, Join us^ won't you. I've made an interesting observation from Damron's new "Address Book" I * It's a ged-damn riot to wotk with Te that just came out. If it weren't for quila Avila and Jimmie (the Homey Greyhound and Trailways in these Uni Owl) Cook, and to be beautifully sup ted States^ some tomu, cities and ported by Cadillac Chuck, the real states wouldn't have anything gay. Al honest to goodness Mike Keeler, Phil so notice that Holiday Inns are picking lip, Tom , Ed, Crazy Gracie, and a up much popularity for the gay travel host of others who are real dear and de ing salesman and representatives that lightful people. All Right! I! !!! toavel throughout tire country. The bar in a Holiday Inn, late at nite, in many cities and towns is the only place a r o u n d TOWN; MY BACKYARD 9 where gay monkey business can be con> Bon Voyage to Richard Dickerson and ducted. -

Emergency Powers of the Executive: the President's Authority When All

EMERGENCY POWERS OF THE EXECUTIVE: THE PRESIDENT’S AUTHORITY WHEN ALL HELL BREAKS LOOSE * JOSHUA L. FRIEDMAN I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 265 I. THE AXIS OVERSIGHT ............................................................................. 268 A. Executive Commander in Chief Powers ........................................ 268 B. Judicial Oversight of Executive Powers ........................................ 273 C. Legislative Oversight of Executive Powers ................................... 274 III. THE ENUMERATED EMERGENCY POWERS OF THE EXECUTIVE BRANCH ........................................................................ 278 A. Emergency Powers ........................................................................ 278 B. Posse Comitatus ............................................................................ 283 C. Martial Law ................................................................................... 286 D. Immediate Response ...................................................................... 291 IV. IMPLICATIONS OF EXPANDED EXECUTIVE POWERS ON PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCIES ........................................... 296 A. Emergence of Related Cases ......................................................... 297 B. Public Health Legislation .............................................................. 299 C. Current Application to Emergencies ............................................. 301 V. CONCLUSION – THE PRINCIPLE OF NECESSITY AS A GLOSS -

The Grass Is Singing, the Lying Days and Disgrace

The Politics of Race, Culture and Gender in Three South African Novels: The Grass is Singing, The Lying Days and Disgrace Sadia Ambreen Khan Student ID: 14163006 Department of English and Humanities December 2015 Khan 2 The Politics of Race, Culture and Gender in Three South African Novels: The Grass is Singing, The Lying Days and Disgrace A Thesis Submitted to The Department of English and Humanities of BRAC University By Sadia Ambreen Khan Student ID: 14163006 In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in English December, 2015 Khan 3 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to Almighty Allah for enabling me to come this far: for giving me patience, strength and courage to undertake this journey. To both Papa and Ammu for their constant encouragement, support and kindness – I owe my life to you. My father whose dream it was to see me complete this degree, passed away in the midst of my first semester during this journey – I hope you come to know that the dream is now a reality. If it had not been for the prayers, support and inspiration of my father-in-law, who watched and took care of my two sons during my classes, this would not have been possible – my earnest gratitude to him. I would like to thank my husband Zubaer for his support and confidence in me. Thanks are due to my family members, especially my eldest brother Tanveer, for their guidance and support. Thank you Zakia – my best friend – for providing the best stress management free of cost. -

Autorità Per Le Garanzie Nelle Comunicazioni Direzione Contenuti Audiovisivi

Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni Direzione Contenuti Audiovisivi Prot. n. DDA/0000109 dell’11 gennaio 2019 Comunicazione di avvio del procedimento istruttorio relativo all’istanza DDA/1755, ai sensi del combinato disposto dell’art. 7 del Regolamento allegato alla delibera n. 680/13/CONS e dell’art. 8, comma 3, della legge 7 agosto 1990, n. 241. (Procedimento n. 948/DDA/LC) Con istanza DDA/1755, pervenuta in data 8 gennaio 2019 (prot. n. DDA/0000090), è stata segnalata dalla FPM (Federazione contro la pirateria musicale e multimediale), in qualità di soggetto legittimato, giusta delega delle società Warner Music Group, Universal Music Group e Sony Music Entertainment, detentrici dei diritti di sfruttamento sulle opere oggetto di istanza, la presenza di una significativa quantità di opere di carattere sonoro, sul sito internet https://1fichier.com, in presunta violazione della legge 22 aprile 1941, n. 633, tra cui sono specificamente indicate a titolo esemplificativo e non esaustivo, le seguenti: TITOLARE ARTISTA TITOLO LINK Warner Music Full Capadocia <omissis> Group Warner Music <omissis> Phil Collins The singles Group Warner Music <omissis> Tarque Tarque Group Warner Music <omissis> Mac Miller Swimming Group Warner Music <omissis> Wiz Khalifa Rolling papers 2 Group Warner Music <omissis> Ciara Level up Group Warner Music <omissis> Pastora Soler La calma directo Group Warner Music <omissis> Architects Holy hell Group Universal Music Eskimo <omissis> Crystals Group Callboy Universal Music About the young <omissis> The jam Group -

Eminem the Complete Guide

Eminem The Complete Guide PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 01 Feb 2012 13:41:34 UTC Contents Articles Overview 1 Eminem 1 Eminem discography 28 Eminem production discography 57 List of awards and nominations received by Eminem 70 Studio albums 87 Infinite 87 The Slim Shady LP 89 The Marshall Mathers LP 94 The Eminem Show 107 Encore 118 Relapse 127 Recovery 145 Compilation albums 162 Music from and Inspired by the Motion Picture 8 Mile 162 Curtain Call: The Hits 167 Eminem Presents: The Re-Up 174 Miscellaneous releases 180 The Slim Shady EP 180 Straight from the Lab 182 The Singles 184 Hell: The Sequel 188 Singles 197 "Just Don't Give a Fuck" 197 "My Name Is" 199 "Guilty Conscience" 203 "Nuttin' to Do" 207 "The Real Slim Shady" 209 "The Way I Am" 217 "Stan" 221 "Without Me" 228 "Cleanin' Out My Closet" 234 "Lose Yourself" 239 "Superman" 248 "Sing for the Moment" 250 "Business" 253 "Just Lose It" 256 "Encore" 261 "Like Toy Soldiers" 264 "Mockingbird" 268 "Ass Like That" 271 "When I'm Gone" 273 "Shake That" 277 "You Don't Know" 280 "Crack a Bottle" 283 "We Made You" 288 "3 a.m." 293 "Old Time's Sake" 297 "Beautiful" 299 "Hell Breaks Loose" 304 "Elevator" 306 "Not Afraid" 308 "Love the Way You Lie" 324 "No Love" 348 "Fast Lane" 356 "Lighters" 361 Collaborative songs 371 "Dead Wrong" 371 "Forgot About Dre" 373 "Renegade" 376 "One Day at a Time (Em's Version)" 377 "Welcome 2 Detroit" 379 "Smack That" 381 "Touchdown" 386 "Forever" 388 "Drop the World" -

Welcoming Ignorance and Ostracizing Good Judgment

WELCOMING IGNORANCE AND OSTRACIZING GOOD JUDGMENT Understanding the production of social realities in the current representation of Islam and Muslims in the German printed press MA Thesis Anna Dilancea S2896389 First Supervisor: Dr. K. E. Knibbe Second Reader: Dr. J. Tarusarira September 2015 – August 2016 For the completion of the Master Program: Religion, Conflict & Globalization Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Abstract This thesis examines the production of social realities in the current representations of Islam and Muslims in the German printed press, namely, Der Spiegel and Focus. Louis Dumont’s theory of hierarchy of values was employed to grasp the specifics of the German integration policy, and its impact on the collective representations of German nationality. It has been argued that the representations of Islam and Muslims in the German media space are strongly influenced by Orientalism and the securitization of migration issue. Both concepts have led to the racialization of religion, which enables cultural othering of German Muslims and Muslim immigrants in the press. The emphasis on their otherness because of Islam turns them into religious subjects and places them at odds with the nation-state, which alters the set of liberties and duties for them as (future) citizens, depriving them of their right not to be abused. A set of recommendations for the press is suggested on how to address the issues of the Islamic State and the refugee crisis to foster acceptance of newcomers and mutual respect. Keywords: immigration, Germany, hierarchy of values, Islam, Orientalism, securitization, minority rights, human rights, cultural othering. 2 Table of contents Introduction………………………………………………………………..........………....4 1. Chapter 1 The media and the production of social realities.............................................7 Section 1.1 Conclusion........................................................................................................10 2.