Effects of Culling Intensity on Diel and Seasonal Activity Patterns of Sika Deer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exotic Big Game: a Controversial Resource Stephen Demarals, David A

RANGELANDS12(2), April 1990 121 operation was substantially higher because of the addi- allocating15% of the fixed vehiclecosts to the enterprise, tional driving associated with guiding hunters and may the break-even charge is $77.90 per hunter day. In com- also involve picking up hunters in town. Providing guid- paring the break-even chargeswith the estimated fee of ing services requiresadditional labor and includesa cost $111.93, it appears this option is also profitable. for the operator to becomelicensed as an outfitter and Discussion and Conclusions This is a in if the guide. requirement Wyoming hunting Additional income was the reason cited enterpriseused landsnot owned by the operator, includ- primary by lands, or if are hired the operators for beginning a recreation enterprise. While ing public guides by operator. ranch recreationhas the to earna realiz- The budget for Example 2 is shown in Table 2. In this potential profit, the breakeven is hunter ing that potential dependson each operator'ssituation. example charge $24.81 per day. evaluate his the break-even with the estimated fee Eachoperator must particularsituation and Comparing charge consider suchas with the of $36.32 that this of any subjectivefactors, dealing per day (Table 1) suggests type when a ranch recreation is also public, assessing the potential of operation profitable. When landowners and are able to Example 3 describes an agricultural operation that pro- enterprise. recognize realize a situation and other vides 14,400 acres for deer and The profitable through hunting antelope hunting. recreation activitieson their land, wildlife habitat will be hunting enterprise operates for 28 days with thirty-five viewed as an asset and not a customershunting an average of four days per hunteror liability. -

Species Fact Sheet: Sika Deer (Cervus Nippon) [email protected] 023 8023 7874

Species Fact Sheet: Sika Deer (Cervus nippon) [email protected] www.mammal.org.uk 023 8023 7874 Quick Facts Recognition: A medium-sized deer. Has a similar spotted coat to fallow deer in summer, but usually is rougher, thicker, dark grey-brown in winter. Tail is shorter than fallow deer, but with similar white “target” and black margins. Usually has a distinctive “furrowed brow” look, and if seen well, evident white spots on the limbs, marking the site of pedal glands. Males have rounded, not pamate, antlers, looking like a small version of a red deer stag’s antlers. Size: 138-179 cm; Tail length: 14-21cm; Shoulder height 50-120 cm. Weight: Males 40-63kg; females 31-44kg. Life Span: Maximum recorded lifespan in captivity is 26 years; 16 in the wild. Distribution & Habitat Sika are native to SE China, including Taiwan, Korea and Japan. It was introduced to Powerscourt Park, Co Wicklow, Ireland, in 1860, and to London Zoo. Sika then spread to many other parks and escaped or were deliberately released; in some cases they were deliberately released into surrounding woodlands to be hunted on horseback. This resulted in feral populations S England (especially Dorset and the New Forest), in the Forest of Bowland and S Cumbria, and, especially, in Scotland. It is still spreading. Its preference for conifer plantations, especially the thick young stages, has been a big advantage to it. It can reach densities up to 45/km2 in prime habitat. General Ecology Behaviour They typically live in small herds of 6-7 animals, at least in more open habitats, but in dense cover may only live in small groups of 1-3 only. -

Estimating Sika Deer Abundance Using Camera Surveys

ESTIMATING SIKA DEER ABUNDANCE USING CAMERA SURVEYS by Sean Q. Dougherty A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Wildlife Ecology Fall 2010 Copyright 2010 Sean Q. Dougherty All Rights Reserved ESTIMATING SIKA DEER ABUNDANCE USING CAMERA SURVEYS by Sean Q. Dougherty Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Jacob L. Bowman, Ph.D. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Douglas W. Tallamy, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Robin W. Morgan, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Agriculture & Natural Resources Approved: ___________________________________________________________ Charles G. Riordan, Ph.D. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the funding sources that made my research possible; the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources Research Partnership Grant, the University of Delaware Graduate School, the University of Delaware McNair Scholar’s program, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, University of Delaware Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology, the West Virginia University McNair Scholar’s program, and Tudor Farms LLC. I would also like to thank my committee members Jake Bowman, Greg Shriver, Brian Eyler, and the staff Tudor Farms LLC for all the support and invaluable advice with all aspects of my research and fieldwork. All my friends and family have been especially valuable for their love and support throughout all my endeavors. Finally, I have to acknowledge Traci Hunt for her support, advice and hours of attentiveness throughout the writing portion of my thesis. -

Reeves' Muntjac Populations Continue to Grow and Spread Across Great

European Journal of Wildlife Research (2021) 67:34 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-021-01478-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Reeves’ muntjac populations continue to grow and spread across Great Britain and are invading continental Europe Alastair I. Ward1 & Suzanne Richardson1 & Joachim Mergeay2,3 Received: 27 August 2020 /Revised: 18 November 2020 /Accepted: 5 March 2021 # The Author(s) 2021 Abstract The appropriate response for controlling an invasive non-native species depends on the extent to which its invasion has progressed, which can be revealed by information on its distribution and abundance. Reeves’ muntjac is a native deer to China and Taiwan, but has been introduced and become well-established in Great Britain. Moreover, in recent years, reports and verified records in the wild from other European countries have become more frequent. We reviewed the status of Reeves’ muntjac in Britain and evaluated its national range expansion from 2002 to 2016. While the British population appears to have tripled in size since 1995, the rate at which it has expanded its range seems to have peaked at approximately 12% per year between 2002 and 2005 and has since declined. We also consolidated observations on its international distribution, including a conservative evaluation of its presence in zoological collections. We predict that this species could expand its range to include every European country, although the availability of suitable landcover and climate is likely to vary substantially between countries. To prevent the significant impacts to conservation interests that have been observed in Great Britain from extending across Europe, national administrations should consider eradicating Reeves’ muntjac while that is still feasible. -

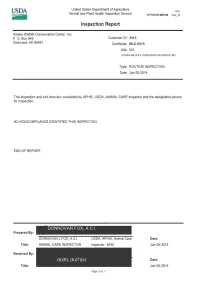

AWA IR C-AK Secure.Pdf

United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 3415 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 25-JUN-14 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 3415 96-C-0015 001 ALASKA WILDLIFE 25-JUN-14 CONSERVATION CENTER INC. Count Species 000002 Canadian lynx 000004 Reindeer 000009 Muskox 000004 Moose 000002 North American black bear 000003 Brown bear 000001 North American porcupine 000130 American bison 000001 Red fox 000021 Elk 000177 Total United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 7106 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 15-SEP-14 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 7106 96-C-0024 001 S.A.A.M.S 15-SEP-14 Count Species 000008 Stellers northern sealion 000006 Harbor seal 000003 Sea otter 000017 Total United States Department of Agriculture Customer: 7106 Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service Inspection Date: 24-JUN-15 Animal Inspected at Last Inspection Cust No Cert No Site Site Name Inspection 7106 96-C-0024 001 S.A.A.M.S 24-JUN-15 Count Species 000008 Stellers northern sealion 000006 Harbor seal 000014 Total DBARKSDALE United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service 2016082567946548 Insp_id Inspection Report S.A.A.M.S Customer ID: 7106 P. O. Box 1329 Certificate: 96-C-0024 Seward, AK 99664 Site: 001 S.A.A.M.S Type: ROUTINE INSPECTION Date: 26-SEP-2016 No non-compliant items identified during this inspection. This inspection and exit briefing was conducted with facility representatives. -

Seasonal Differences in Rumen Bacterial Flora of Wild Hokkaido Sika

Seasonal differences in rumen bacterial flora of wild Hokkaido sika deer and partial characterization of an unknown Title bacterial group possibly involved in fiber digestion in winter Author(s) Yamano, Hidehisa; Ichimura, Yasuhiro; Sawabe, Yoshihiko; Koike, Satoshi; Suzuki, Yutaka; Kobayashi, Yasuo Animal science journal, 90(6), 790-798 Citation https://doi.org/10.1111/asj.13203 Issue Date 2019-06 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/78283 This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: "Seasonal differences in rumen bacterial flora of wild Hokkaido sika deer and partial characterization of an unknown bacterial group possibly involved in fiber digestion in Rights winter", Animal Science Journal 90(6) 790-798,June 2019, which has been published in final form at https://doi.org/10.1111/asj.13203. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Use of Self-Archived Versions. Type article (author version) File Information ASJ_Yamano et al._final.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP 1 1 ORIGINAL ARTICLE 2 3 Seasonal differences in rumen bacterial flora of wild Hokkaido sika deer and partial 4 characterization of an unknown bacterial group possibly involved in fiber digestion in winter 5 6 Hidehisa Yamano, Yasuhiro Ichimura, Yoshihiko Sawabe, Satoshi Koike, Yutaka Suzuki and Yasuo 7 Kobayashi* 8 9 Graduate School of Agriculture, Hokkaido University, Hokkaido 060-8589, Japan 10 11 Correspondence 12 Yasuo Kobaayashi, Graduate School of Agriculture, Hokkaido University, 13 Kita, Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan 14 E mail: [email protected] 15 16 Funding information 17 Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan, 18 Grant/Award Numbers 15580231 and 17380157 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 2 1 ABSTRACT 2 Rumen digesta was obtained from wild Hokkaido sika deer to compare bacterial flora between 3 summer and winter. -

Mixed-Species Exhibits with Pigs (Suidae)

Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) Written by KRISZTIÁN SVÁBIK Team Leader, Toni’s Zoo, Rothenburg, Luzern, Switzerland Email: [email protected] 9th May 2021 Cover photo © Krisztián Svábik Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Use of space and enclosure furnishings ................................................................... 3 Feeding ..................................................................................................................... 3 Breeding ................................................................................................................... 4 Choice of species and individuals ............................................................................ 4 List of mixed-species exhibits involving Suids ........................................................ 5 LIST OF SPECIES COMBINATIONS – SUIDAE .......................................................... 6 Sulawesi Babirusa, Babyrousa celebensis ...............................................................7 Common Warthog, Phacochoerus africanus ......................................................... 8 Giant Forest Hog, Hylochoerus meinertzhageni ..................................................10 Bushpig, Potamochoerus larvatus ........................................................................ 11 Red River Hog, Potamochoerus porcus ............................................................... -

Experimental Test of the Impacts of Feral Hogs on Forest Dynamics and Processes in the Southeastern US

Forest Ecology and Management 258 (2009) 546–553 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Experimental test of the impacts of feral hogs on forest dynamics and processes in the southeastern US Evan Siemann a,*, Juli A. Carrillo a, Christopher A. Gabler a, Roy Zipp b, William E. Rogers c a Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Rice University, 6100 Main St., Houston, TX 77005, USA b North Cascades National Park, US Park Service, Sedro-Woolley, WA 98284, USA c Department of Ecosystem Science and Management, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The foraging activities of nonindigenous feral hogs (Sus scrofa) create widespread, conspicuous soil Received 22 November 2008 disturbances. Hogs may impact forest regeneration dynamics through both direct effects, such as Received in revised form 24 March 2009 consumption of seeds, or indirectly via changes in disturbance frequency or intensity. Because they Accepted 30 March 2009 incorporate litter and live plant material into the soil, hogs may also influence ground cover and soil nutrient concentrations. We investigated the impacts of exotic feral hogs in a mixed pine-hardwood Keywords: forest in the Big Thicket National Preserve (Texas, USA) where they are abundant. We established sixteen Big thicket 10 m  10 m plots and fenced eight of them to exclude feral hogs for 7 years. Excluding hogs increased Biological invasions the diversity of woody plants in the understory. Large seeded (>250 mg) species known to be preferred Disturbance Exclosures forage of feral hogs all responded positively to hog exclusion, thus consumption of Carya (hickory nuts), Forest regeneration Quercus (acorns), and Nyssa seeds (tupelo) by hogs may be causing this pattern. -

WSC 11-12 Conf 14 Layout

Joint Pathology Center Veterinary Pathology Services WEDNESDAY SLIDE CONFERENCE 2011-2012 Conference 14 25 January 2012 CASE I: NADC MVP-2 (JPC 3065874). Gross Pathology: The deer was of normal body condition with adequate deposits of body fat. There Signalment: 5-month-old female white-tailed deer was crusty exudate around the eyes. Multifocal areas (Odocoileus virginianus). of hemorrhage were seen in the heart (epicardial and endocardial), lungs, kidney, adrenal glands, spleen, History: Observed depressed, listless. Physical exam small and large intestines (mucosal and serosal revealed fever (102.5 F), mild dehydration, normal surfaces) and along the mesenteric border, mesenteric auscultation of heart and lungs, no evidence of lymph nodes and iliopsoas muscles. Multifocal ulcers diarrhea. Treated with IV fluids, antibiotics and a non- were present in the pyloric region of the abomasum. steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Deer died within 5 hours. Laboratory Results: PCR for OvHV-2: positive PCR for EHV: negative PCR for Bluetongue virus: negative PCR for BVD: negative Contributor’s Histopathologic Description: Within the section of myocardium there is accentuation of medium to large arteries due to the infiltration of the vascular wall and perivascular spaces by inflammatory cells. Numerous lymphocytes and fewer neutrophils invade, and in some cases, efface the vessel wall. Fibrinoid degeneration and partially occluding fibrinocellular thrombi are present in the most severely affected vessels. Less affected vessels are characterized by large, rounded endothelial cells and intramural lymphocytes and neutrophils. Within the myocardium are multifocal areas of hemorrhage and scattered infiltrates of lymphocytes and macrophages. 1-1. Heart, white-tailed deer. Necrotizing arteritis characterized by Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis: marked expansion of the wall by brightly eosinophilic protein, numerous inflammatory cells, and cellular debris (fibrinoid necrosis). -

In New Zealand

NZ ISSN 0048-0134 NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF FORESTRY SCIENCE New Zealand Forest Service, Forest Research Institute, Rotorua Editor: H. V. Hinds VOLUME 3 JULY 1973 NUMBER 2 CHARACTERISTICS, LIBERATION AND DISPERSAL OF SIKA DEER (CERVUS NIPPON) IN NEW ZEALAND MAVIS M. DAVIDSONI Forest Research Institute, New Zealand Forest Service (Received for publication 26 June 1972) ABSTRACT Morphological characterisation of sika deer is attempted by using a discriminant function analysis based on autopsy data from a mixed population of sika and red deer. There is evidence of hybridism between the two species. The history of liberation and dispersal from the northern Kaimanawa Mountains is illustrated by two dispersal maps based on sighting records and roar data. Spread was predominantly through shrubland or shrubland/forest ecotones. Dispersal rates varying from 0.6 to 1.5km/yr are estimated for the period 1905-30, and then for decades to 1970, showing an acceleration after 1950 (possibly due to human activity pushing the deer westwards into indigenous forest regions). INTRODUCTION Sika deer (Cervus nippon) were liberated near Oamaru in the South Island of New Zealand in 1885 and in the Kaimanawa Mountains of the North Island in 1905. Only the second release, which was with deer from the Duke of Bedford's Woburn herd, proved successful. Since the first stalking season for sika in 1925 (McKinnon and Coughlan*, I960) the species has been prized for its trophy value (Thornton, 1933; t Address: New Zealand Forest Service, Private Bag, Wellington * Lanna Coughlan, now Lanna Brown N.Z. JI For. Sci. 3 (2): 153-180 154 New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science Vol. -

The First High-Quality Reference Genome of Sika Deer Provides

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443962; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 The First High-Quality Reference Genome of Sika Deer Provides 2 Insights for High-Tannin Adaptation 3 4 Xiumei Xing*,#,1, Cheng Ai#,2, Tianjiao Wang#,1, Yang Li#,1, Huitao Liu#,1, Pengfei Hu#,1, 5 Guiwu Wang#,1, Huamiao Liu1, Hongliang Wang1, Ranran Zhang1, Junjun Zheng1, 6 Xiaobo Wang2, Lei Wang1, Yuxiao Chang2, Qian Qian2, Jinghua Yu3, Lixin Tang1, 7 Shigang Wu2, Xiujuan Shao2, Alun Li2, Peng Cui2, Wei Zhan4, Sheng Zhao2, Zhichao 8 Wu2, Xiqun Shao1, Yimeng Dong1, Min Rong1, Yihong Tan3, Xuezhe Cui1, Shuzhuo 9 Chang1, Xingchao Song1, Tongao Yang1, Limin Sun1, Yan Ju1, Pei Zhao1, Huanhuan 10 Fan1, Ying Liu1, Xinhui Wang1, Wanyun Yang1, Min Yang1, Tao Wei1, Shanshan 11 Song1, Jiaping Xu1, Zhigang Yue1, Qiqi Liang*,5, Chunyi Li*,1, Jue Ruan*,2, Fuhe 12 Yang*,1 13 14 1 Key Laboratory of Genetics, Breeding and Reproduction of Special Economic Animals, 15 Ministry of Agriculture, Institute of Special Animal and Plant Sciences, Chinese 16 Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Changchun 130112, China 17 2 Guangdong Laboratory for Lingnan Modern Agriculture, Genome Analysis 18 Laboratory of the Ministry of Agriculture, Agricultural Genomics Institute at Shenzhen, 19 Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Shenzhen 518120, China 20 3 CAS Key Laboratory of Forest Ecology and Management, Institute of Applied Ecology, 21 Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenyang 110016, China 22 4 Annoroad Gene Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd, Beijing Economic-Technological 23 Development Area, Beijing 100176, China 24 5 Novogene Bioinformatics Institute, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100083, China 25 26 # These authors contributed equally. -

Mammal Review © 2010 Mammal Society, Mammal Review, 41, 313–325 314 R

Mammal Rev. 2011, Volume 41, No. 4, 313–325. Printed in Singapore. REVIEW Distribution and range expansion of deer in Ireland Ruth F. CARDEN* National Museum of Ireland – Natural History, Merrion Street, Dublin 2, Ireland. E-mail: [email protected] Caitríona M. CARLIN Applied Ecology Unit, Centre for Environmental Science, Environmental Change Institute, National University of Ireland Galway, Ireland. E-mail: [email protected] Ferdia MARNELL National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of the Environment, Heritage & Local Government, 7 Ely Place, Dublin 2, Ireland. E-mail: [email protected] Damian MCELHOLM The British Deer Society, Northern Ireland Branch, c/o The British Deer Society, The Walled Garden, Burgate Manor, Fordingbridge, Hampshire SP6 1EF, Britain. E-mail: [email protected] John HETHERINGTON The British Deer Society, Northern Ireland Branch, c/o The British Deer Society, The Walled Garden, Burgate Manor, Fordingbridge, Hampshire SP6 1EF, Britain. E-mail: [email protected] Martin P. GAMMELL Department of Life and Physical Sciences, Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology, Dublin Road, Galway, Ireland. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT 1. Throughout Europe, the range of many deer species is expanding. We provide current distribution maps for red deer Cervus elaphus, sika Cervus nippon, fallow deer Dama dama and muntjac deer Muntiacus sp. in Ireland, and estimates of range expansion rates for red deer, sika and fallow deer. 2. There was a considerable expansion in the ranges of red deer, sika and fallow deer between 1978 and 2008. The compound annual rate of expansion was 7% for red deer, 5% for sika and 3% for fallow deer.