Context, Framework and the Way Forward to Ending TB in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prospectus 2020-21

ªÀÄAUÀ¼ÀÆgÀÄ «±Àé«zÁ央AiÀÄ MANGALORE UNIVERSITY ¸ÁßvÀPÉÆÃvÀÛgÀ ¥ÀzÀ«AiÀÄ «ªÀgÀUÀ¼ÀÄ DAiÉÄÌ DzsÁjvÀ ±ÉæÃAiÀiÁAPÀ ¥ÀzÀÞw POST GRADUATE DEGREE PROGRAMMES CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM ªÀiÁ»w ¥ÀŸÀÛPÀ PROSPECTUS 2020-21 Mangalagangothri - 574199 Dakshina Kannada District, Karnataka State India. VISION TO EVOLVE AS A NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDIES AND TO CULTIVATE QUALITY HUMAN RESOURCE MISSION • To provide Excellent Academic, Physical, Administrative, Infrstructural and Moral ambience. • To promote Quality and Excellence in Teaching, Learning and Research. • To preserve and promote uniqueness and novelty of regional languages, folklore, art and culture. • To contribute towards building a socially sensitive, humane and inclusive society. • To cultivate critical thinking that can spark creativity and innovation. Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Instructions 8 3. Programmes Offered 9 4. Eligibility Conditions 13 5. Admission Procedure 32 6. Intake 36 7. Fee Structure 40 8. Location of Post Graduate Departments 45 9. Scholarships 47 10. Central Facilities 49 11. Contact Details 53 ªÀÄAUÀ¼ÀÆgÀÄ «±Àé«zÁ央AiÀÄ MANGALORE UNIVERSITY ¥Àæ¸ÁÛªÀ£É zÀQët PÀ£ÀßqÀ, GqÀĦ ºÁUÀÆ PÉÆqÀUÀÄ f¯ÉèUÀ¼À G£ÀßvÀ ²PÀëtzÀ CUÀvÀåUÀ¼À£ÀÄß ¥ÀÇgÉʸÀĪÀ GzÉÝñÀ¢AzÀ ªÀÄAUÀ¼ÀÆgÀÄ «±Àé«zÁ央AiÀĪÀÅ ¸À¥ÉÖA§gï 10, 1980gÀAzÀÄ ¸ÁÜ¥À£ÉUÉÆArvÀÄ. G£ÀßvÀ ªÀÄvÀÄÛ ºÉaÑ£À ±ÉÊPÀëtÂPÀ CzsÀåAiÀÄ£À ªÀÄvÀÄÛ ¸ÀA±ÉÆÃzsÀ£ÉAiÀÄ ªÀÄÄRå PÉÃAzÀæªÁVgÀĪÀ ªÀÄAUÀ¼ÀÆgÀÄ «±Àé«zÁ央AiÀÄzÀ ¥ÁæPÀÈwPÀªÁV ¸ÀÄAzÀgÀªÁzÀ vÁtzÀ°èzÉ. ªÀÄAUÀ¼ÀÆgÀÄ «±Àé«zÁ央AiÀĪÀÅ £ÀªÀÄä £Ár£À ºÉªÉÄäAiÀÄ «±Àé«zÁ央AiÀÄUÀ¼À°è MAzÁVzÉ. G£ÀßvÀ ²PÀët gÀAUÀzÀ ¥ÁæaãÀ ªÀÄvÀÄÛ ¥Àæw¶×vÀªÁzÀ PÉ®ªÀÅ «zÁå ¸ÀA¸ÉÜUÀ¼ÀÄ ªÀÄAUÀ¼ÀÆgÀÄ «±Àé«zÁ央AiÀÄzÀ PÀPÉëAiÀÄ°è §gÀÄvÀÛªÉ. -

Indian Red Cross Society, D.K District Branch Life Members Details As on 02.10.2015

Indian Red Cross Society, D.K District Branch Life Members details as on 02.10.2015 Sri. J.R. Lobo, Sri. RTN. P.H.F William M.L.A, D'Souza, Globe Travels, Deputy Commissioner Jency, Near Ramakrishna 1 2 3 G06, Souza Arcade, Balmatta D.K District Tennis Court, 1st cross, Shiva Road, Mangalore-2 Bagh, Kadri, M’lore – 2 Ph: 9845080597 Ph: 9448375245 Sri. RTN. Nithin Shetty, Rtn. Sathish Pai B. Rtn. Ramdas Pai, 301, Diana APTS, S.C.S 4 5 Bharath Carriers, N.G Road 6 Pais Gen Agencies Port Road, Hospital Road, Balmatta, Attavar, Mangalore - 1 Bunder, Mangalore -1 Mangalore - 2 Sri. Vijaya Kumar K, Rtn. Ganesh Nayak, Rtn. S.M Nayak, "Srishti", Kadri Kaibattalu, Nayak & Pai Associates, C-3 Dukes Manor Apts., 7 8 9 D.No. 3-19-1691/14, Ward Ganesh Kripa Building, Matadakani Road, No. 3 (E), Kadri, Mangalore Carstreet, Mangalore 575001 Urva, Mangalore- 575006 9844042837 Rtn. Narasimha Prabhu RTN. Ashwin Nayak Sujir RTN. Padmanabha N. Sujir Vijaya Auto Stores "Varamahalaxmi" 10 "Sri Ganesh", Sturrock Road, 11 12 New Ganesh Mahal, 4-5-496, Karangalpady Cross Falnir, Mangalore - 575001 Alake, Mangalore -3 Road, Mangalore - 03 RTN. Rajendra Shenoy Rtn. Arun Shetty RTN. Rajesh Kini 4-6-615, Shivam Block, Excel Engineers, 21, Minar 13 14 "Annapoorna", Britto Lane, 15 Cellar, Saimahal APTS, Complex New Balmatta Road, Falnir, Mangalore - 575001 Karangalpady, Mangalore - 03 Mangalore - 1 Sri. N.G MOHAN Ravindranath K RTN. P.L Upadhya C/o. Beta Agencies & Project 803, Hat Hill Palms, Behind "Sithara", Behind K.M.C Private Ltd., 15-12-676, Mel Indian Airlines, Hat Hill Bejai, 16 17 18 Hospital, Attavar, Nivas Compound, Kadri, Mangalore – 575004 Mangalore - 575001 Mangalore – 02. -

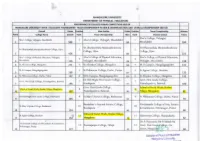

Franchisees in the State of Karnataka (Other Than Bangalore)

Franchisees in the State of Karnataka (other than Bangalore) Sl. Place Location Franchisee Name Address Tel. No. No. Renuka Travel Agency, Opp 1 Arsikere KEB Office K Sriram Prasad 9844174172 KEB, NH 206, Arsikere Shabari Tours & Travels, Shop Attavara 2 K.M.C M S Shabareesh No. 05, Zephyr Heights, Attavar, 9964379628 (Mangaluru) Mangaluru-01 No 17, Ramesh Complex, Near Near Municipal 3 Bagepalli S B Sathish Municipal Office, Ward No 23, 9902655022 Office Bagepalli-561207 New Nataraj Studio, Near Private Near Private Bus 9448657259, 4 Balehonnur B S Nataraj Bus Stand, Iliyas Comlex, Stand 9448940215 Balehonnur S/O U.N.Ganiga, Barkur 5 Barkur Srikanth Ganiga Somanatheshwara Bakery, Main 9845185789 (Coondapur) Road, Barkur LIC policy holders service center, Satyanarayana complex 6 Bantwal Vamanapadavu Ramesh B 9448151073 Main Road,Vamanapadavu, Bantwal Taluk Cell fix Gayathri Complex, 7 Bellare (Sulya) Kelaginapete Haneef K M 9844840707 Kelaginapete, Bellare, Sulya Tq. Udayavani News Agent, 8 Belthangady Belthangady P.S. Ashok Shop.No. 2, Belthangady Bus 08256-232030 Stand, Belthangady S/O G.G. Bhat, Prabhath 9 Belthangady Belthangady Arun Kumar 9844666663 Compound, Belthangady 08282 262277, Stall No.9, KSRTC Bus Stand, 10 Bhadravathi KSRTC Bus Stand B. Sharadamma 9900165668, Bhadravathi 9449163653 Sai Charan Enterprises, Paper 08282-262936, 11 Bhadravathi Paper Town B S Shivakumar Town, Bhadravathi 9880262682 0820-2562805, Patil Tours & Travels, Sridevi 2562505, 12 Bramhavara Bhramavara Mohandas Patil Sabha bhavan Building, N.H. 17, 9845132769, Bramhavara, Udupi Dist 9845406621 Ideal Enterprises, Shop No 4, Sheik Mohammed 57A, Afsari Compound, NH 66, 8762264779, 13 Bramhavara Dhramavara Sheraj Opposite Dharmavara 9945924779 Auditorium Brahmavara-576213 M/S G.R Tours & Travels, 14 Byndur Byndoor Prashanth Pawskar Building, N.H-17, 9448334726 Byndoor Sl. -

All India Council for Technical Education (A Statutory Body Under Ministry of HRD, Govt

All India Council for Technical Education (A Statutory body under Ministry of HRD, Govt. of India) Nelson Mandela Marg,Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-110070 Website: www.aicte-india.org APPROVAL PROCESS 2019-20 Extension of Approval (EoA) F.No. South-West/1-4262374102/2019/EOA Date: 10-Apr-2019 To, The Principal Secretary (Hr. & Tech Education) Govt. of Karnataka, K. G.S., 6th Floor, M.S. Building, R. N. 645,Dr. B. R. Ambedkar Road, Bangalore-560001 Sub: Extension of Approval for the Academic Year 2019-20 Ref: Application of the Institution for Extension of approval for the Academic Year 2019-20 Sir/Madam, In terms of the provisions under the All India Council for Technical Education (Grant of Approvals for Technical Institutions) Regulations 2018 notified by the Council vide notification number F.No.AB/AICTE/REG/2018 dated 31/12/2018 and norms standards, procedures and conditions prescribed by the Council from time to time, I am directed to convey the approval to Permanent Id 1-3747150941 Application Id 1-4262374102 Name of the Institute NITTE INSTITUTE OF Name of the Society/Trust TRUST OF NITTE UNIVERSITY ARCHITECTURE Institute Address PANEER CAMPUS, KOTEKAR- Society/Trust Address 6TH FLOOR, BEERI ROAD,, DERALAKATTE, UNIVERSITY ENCLAVE, MEDICAL DAKSHINA KANNADA, Karnataka, SCIENCES 575018 COMPLEX,,DERALAKATTE,DAKSHI NA KANNADA,Karnataka,575018 Institute Type Deemed University(Private) Region South-West Opted for Change from No Change from Women to Co-Ed NA Women to Co-Ed and vice and vice versa Approved or versa Not Opted for Change of Name -

College Performance

MANGALORE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICAL EDUCATION PERFORMANCE OF COLLEGES IN MUIC COMPETITIONS 2019-20 MANGALORE UNIVERSITY INTER- COLLEGIATE TOURNAMENT- TEAM CHAMPIONSHIP IN MEN & WOMEN SECTION AND OVERALL CHAMPIONSHIP 2019-20 Overall Points Positior Men Section Points Position Team Championship Women Rank College Name Overall Rank Team Championship Men Rank Women Section Points Alva's College, Vidyagiri, Alva's College, Vidyagiri, Moodabidri 1 Alva 's College, Vidyagiri, Moodabidri 1 1 583 299 Moodabidri 284 Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara Sri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara College, Ujir~ 2 2 College, Ujire College, Ujire 2 424 202 222 Ah· a·' College of Physical Education, Vidyagiri, Alva's College of Physical Education, Alva's College of Physical Education, 3 3 3 M,)()dahidri 334 Vidyagiri, Moodabidri 136 Vidyagiri, Moodahidri 198 4 St.Aloysius College, Mangalore 271 4 St.Aloysius College, Mangalore 140 4 M. U.Campus, Mangalagangothri 141 M.U.L'ampus, Mangalagangothri 5 St.Philomena College, Darbc, Puttur 5 St.Agnes College, Bendore 5 266 127 132 6 St.Philomena College, Darbe, Puttur 197 6 M. U. Campus, Mangalagangothri 125 6 St.Aloysius College, Mangalore 131 Dr.B.B.Hegde First Grade College, Govt. First Grade College, GoYt. First Grade College, Vamadapadavu, Bantwal 7 7 7 196 Kundapura 97 Vamadapa<lan1, Bantwal 100 Govt. First Grade College, School of Social Work, Roshni School of Social Work, Roshni Nilaya, Mang?.lore 8 8 8 157 Vamadapadavu, Bantwal 96 Nilaya, Mangalore 81 Dr.B.B.Hegde First -

Minor Research On

Minor Research on Contributions Of The First Parliamentarian To The Development Of Undevided District Of South Canara A – Case Study Submitted To UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION SOUTH WESTERN REGION By Smt. Anitha Kamath K Assistant Professor In Political Science Vivekananda College Puttur Ullal Srinivas Mallya, the first member of the Parliament from Mangalore ( won from Udupi Constituency) was a master planner and a true politician,unlike the present day MP’s who declare themselves No.1-MP doing nothing notable.Ullal Srinivas Mallya was born on 21st of November 1902 into a conservative and traditional Gowda Saraswat Brahmin (GSB) family of Mangalore, known as the Ullal Mallyas. His father was Ullal Manjunath Mallya and mother Rukma Bai. His elder brother was Dr. U. Padmanabha Mallya , who too was a Congress leader for a long time. Young Srinivas Mallya did his primary education at St. Aloysius Primary School upto 8th std, and completed his high school -9th and 10th std at Canara School. Intermediates studies, he pursued at Government College. But it was not academics that interested him, rather it was the ongoing struggle for Independence that caught his fancy. At the tender age of 18, Srinivas Mallya’s restive spirit reached out to Gandhi’s call for joining the freedom movement. What made the young Srinivas give up a life of ease, where he simply needed to lend a helping hand in the already flourishing family wholesale business in Bunder in Mangalore? What promoted him to opt for the strenuous life of a satyagrahi, go underground, court or evade arrest as the need may be and generally give up the comforts of a carefree existence?.Perhaps it was a sound value base that Srinivas Mallya possessed that gave him the strength to turn back on material gains and step into an uncertain, difficult world, that too at such a tender age ideal MP our people’s representatives who have stood in for Mangalore through successive Lok Sabha elections ,only one man seems to pass the litmus test for being adjudged as the ideal MP. -

Journal of Microbiological Methods Comparative Performance of TCBS

Journal of Microbiological Methods 157 (2019) 37–42 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Microbiological Methods journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jmicmeth Comparative performance of TCBS and TSA for the enumeration of trh+ Vibrio parahaemolyticus by direct colony hybridization T Karanth Padyana Anupamaa, Kundar Deekshaa, Ariga Deekshaa, Iddya Karunasagarb, ⁎ Indrani Karunasagara,b, Biswajit Maitia, a Division of Infectious Diseases, Nitte University Centre for Science Education and Research, NITTE (Deemed to be University), Paneer Campus, Deralakatte, Mangaluru 575018, India b NITTE (Deemed to be University), University Enclave, Medical Sciences Complex, Deralakatte, Mangaluru 575018, India ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Vibrio parahaemolyticus is one of the important foodborne pathogens is of public health concern due to the Vibrio parahaemolyticus emergence of pandemic strains causing disease outbreaks worldwide. We evaluated the DNA based colony Colony hybridization hybridization technique for the detection and enumeration of total and pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus from the Digoxigenin-labeled probe bivalve shellfish, clam using non-radioactive, enzyme-labeled probe targeting the tlh and trh genes, respectively. Enumeration The digoxigenin (DIG) labeled probes designed in this study showed 100% specificity by dot blot assay. Colony Seafood hybridization using DIG probes was performed using both non-selective, trypticase soy agar (TSA) and the selective medium, thiosulfate citrate bile salts sucrose (TCBS) agar. Of 32 clam samples analyzed, 71.88% had > 10,000 V. parahaemolyticus cells/g in TSA whereas it was 18.75% in case of TCBS. All the samples showed the presence of total V. parahaemolyticus in TSA and 97% in the case of TCBS. Interestingly, results of the trh+V. -

002 Adyanadka D.NO.492/2A, KEPU VILLAGE, ADYANADKA

Sl. Address No. SOL ID Branch Name Contact email id D.NO.492/2A, KEPU VILLAGE, 002 Adyanadka 9449595621 [email protected] 1 ADYANADKA Sri Krishna Upadhyaya Complex, 003 Airody 9449595625 [email protected] 2 NH66, Near Bus Stand, Sasthana Plot No. 1185, First Floor, Srinivas 005 Almel Nilaya, Indi Road, Near APMC, 9449595573 [email protected] 3 Almel TAPOVANA COMPLEX, SHIRAL 006 Anavatti KOPPA - HANGAL ROAD, 9449595401 [email protected] 4 ANAVATTI Ground Floor, Bharath Complex, 007 Arehalli 9449595402 [email protected] 5 Belur Road, Arehalli 6 009 Arsikere-Main LAKSHMI, B.H.ROAD, ARSIKERE 9449595404 [email protected] “Ganesh Ram Arcade”, No.213, B 010 Ayanur 9449595520 [email protected] 7 H Road, Ayanur Ist FLOOR, LOURDES COMPLEX, 011 Amtady AMTADY, LORETTO POST, 9449595624 [email protected] 8 AMTADY, BANTWAL TALUK. RAMAKRISHNA NILAYA, POST 012 Aikala 9449595622 [email protected] 9 KINNIGOLI, AIKALA Door No. 1/89(11), SY. No. 78/12, Old SY No. 78/4P2, “Sinchana Complex”, Ground Floor, 013 Amasebail 9449595626 [email protected] Amasebail Siddapura Road, Amasebail Village, Kundapura 10 Taluk, Udupi District – 576227 OPP.PUSHPANJALI TALKIES, 014 Agali 8500801827 [email protected] 11 MADAKASIRA ROAD, AGALI. GROUND FLOOR, NO.47/1, SRI 015 Aladangady LAXMI NILAYA, MAIN ROAD, ANE 9449595623 [email protected] 12 MAHAL, ALADANGADY Ist FLOOR, DURGA Udupi-Adi 016 INTERNATIONAL BUILDING, 9449595595 [email protected] Udupi 13 UDUPI-MALPE ROAD, UDUPI BUILDING1(817), OPP.HOTEL Goa-Alto 017 O'COQUEIRO, PANAJI-MAPUSA 9423057235 [email protected] Porvorim 14 HIGH WAY, ALTO PORVORIM SUJATHA COMPLEX, MANIPAL Udupi- 018 CROSS ROAD, AMBAGILU- 9448463283 [email protected] Ambagilu 15 UDUPI CTS No. -

Diksoochi Eng Single Page.Pmd

Diksuchi, towards empowerment of the community TRF TALENT RESEARCH FOUNDATION (R) - 1 - Diksuchi, towards empowerment of the community TRF TALENT RESEARCH FOUNDATION (R) - 2 - Diksuchi, towards empowerment of the community TRF TALENT RESEARCH FOUNDATION (R) MESSAGE Shaikhuna Abdul Rehiman Kunhi Koya Thangal Al Bukahri, Ullal Qazi Islam gives prime importance to education. Talent Research Foundation (R) strives to bring those, who have quit education and find themselves in darkness, back to the process of learning and helps them to march towards light. Let Allah give them Taufik to do more noble work. Let us join hands with them. Shaikuna Twakha Ahmad Musliyar Qazi, Mangalore It is clear from the complexities of problems that the world is facing today, that the onus of reaching the message of Islam to the people with more vigour is on Ulamas and Umaras. Let Talent Research Foundation be the guiding light for those Muslim brethren rambling in darkness with the burden of ignorance. We pay our special thanks to Shaikhuna Abdul Rehman Kunhi Koya Thangal Al Bukahri, Ullal Qazi, Shaikuna Twakha Ahmad Musliyar, Qazi, Mangalore and also to all the dignitaries who have acclaimed our activities and pushed us forward by their words of inspiration and good wishes. Talent Research Foundation (R) Mangalore - 3 - Diksuchi, towards empowerment of the community TRF TALENT RESEARCH FOUNDATION (R) MESSAGE The preamble of Yashpal Committee's Interim Report reads : "The world around us has changed dramatically but our education continues to operate in the same policy frame. There is need for a major paradigm shift in this sector which would not happen with small incremental and unrelated changes here and there." If we have to march forward, achieve progress and stand competition and challenges then education to our children, the future generation, has to be accessible, affordable and qualitative. -

Department of Medical Social Work

DEPARTMENT OF MEDICAL SOCIAL WORK ACTIVITIES OF THE DEPARTMENT AT A GLANCE 1 ACADEMIC Post Graduate Programme-Master of Social Work(MSW) PhD Programme 2 WELFARE & OUTREACH Department of MSW is involved in various welfare activities focusing on the health and well being of the community. These activities include: Social rehabilitation of patients in the community Health Outreach -Medical, Eye screening, Blood donation and School children health screening camps, Health education Health care extension to NGOs and Care homes Coordinating Rural Health Extension Centers 3 TRAINING Field work training of Social Work Degree students posted from external Social Work Education Institutions Training in Personality Development and Communication 4 RESEARCH Department of MSW involved in research in Medical Social Work, NGO Management, Tribal Health, De-addiction, Women Empowerment and Social Science themes. It collaborates with other Academic Departments of the University in doing research in interdisciplinary themes. 5 NETWORKING Networking with NGOs, Corporate Organizations, Rural and Urban Governance Institutions for student field work training and Internship programme MASTER OF SOCIAL WORK PROGRAMME DURATION: Two years with four semesters. ELIGIBILTY: Graduate in any discipline from a recognized University with a minimum of 50% marks in the aggregate. SPECIALIZATION OFFERED 1. Medical and Psychiatric Social Work 2. Human Resource Management SPECIAL FEATURES OF THE COURSE Choice Based Credit System (CBCS) Participatory Teaching–Learning -

LIST of BOS Members in Pre Clinical PG 01 Dr

LIST OF BOS Members in Pre Clinical PG 01 Dr. Meera Chairman, BOS in Pre Clinical PG, Professor & HOD of Biochemistry Mysore Medical College and Research Institute Irwin Road, Mysore- 570 001 02 Dr. Seema Deepak Associate Professor of Anatomy Mysore Medical College and Research Institute Irwin Road, Mysore- 570 001 03 Dr. Yogitha Professor of Anatomy St. John’s Medical College St. John’s National Academy of Health Sciences, Sarjapur Road Bangalore – 560 034 04 Dr. Smrithi Shetty Asso. Prof. & HOD of Physiology A J Institute of Medical Sciences, N.H. 17, Kuntikana, Mangalore – 575004 05 Dr. Priya Ranganath Professor & HOD of Anatomy Bangalore Medical College & Research Institute, Fort, Bangalore -560 002 06 Dr. Maruthi Prasad B.V Professor of Biochemistry Bangalore Medical College & Research Institute, Fort Bangalore- 560 002 07 Dr. Trinesh Gowda Professor & HOD of Anatomy Mandya Institute of Medical Sciences Bangalore-Mysore Road, Mandya Karnataka -571401 08 Dr. Mallikarjun M Professor & HOD of Anatomy Vijayanagar Institute of Medical Sciences, Cantonment, Bellary -583 10 09 Dr. Revathi Professor & HOD of Physiology Mysore Medical College and Research Institute, Irwin Road, Mysore -570 001 10 Dr. Sunitha Pujar Prof. of Biochemistry B V V Sangha’s S. Nijalingappa Medical College & Hanagal Shri Kumareshwara Hospital & Research Centre, Navanagar, Bagalkot – 587 102 11 Dr. Varsha Prof. & HOD of Anatomy Vydehi Institute of Medical Sciences & Research Centre, # 82, EPIP Area, Whitefield, Nallurahalli, Bangalore – 560066 12 Dr. Suman Dambal Associate Prof. of Biochemistry Karnataka Institute of Medical Sciences, Hubli – 580022 13 Dr. Rajani Prof. of Biochemistry JJM Medical College Davangere – 577 004. 14 Dr. -

MANGALORE UNIVERSITY Accredited by NAAC with `A’ Grade

MANGALORE UNIVERSITY Accredited by NAAC with `A’ Grade No. MU/EXB/CR. /2015-16/E.5 Office of the Registrar (Evaluation) Mangalagangothri-574 199 Date: 28.04.2016 NOTIFICATION Sub: Examination Centres for B.A./B.Sc./B.Com./B.S.W./B.Sc. (F.N.D.)/Bachelor Of Visual Arts (B.V.A.) / B.Sc. (Animation and Visual Effects)/B.A. Security & Detective Science degree examinations of May/June 2016. ----------- The following colleges are declared as centres for the University examinations of May/June 2016 for B.A./B.Sc./B.Com./B.S.W./ B.Sc. (F.N.D.)/B.Sc. (Animation and Visual Effects)/B.A. (Security and Detective Science)/ Bachelor of Visual Arts (B.V.A.) degree examinations. 1 1. St. Aloysius Evening College, Mangalore. 2. Besant Women’s College, Mangalore. 3. Besant Evening College, Mangalore. 4. Canara College, Mangalore. 5. University College, Mangalore. 6. Shree Gokarnanatheshwara College, Mangalore 7. Badriya First Grade College, Mangalore. 8. Govinda Dasa College, Surathkal. 9. Vijaya College, Mulki. 10. Poornaprajna College, Udupi. 11. Poornaprajna Evening College, Udupi. 12. M.G.M. College, Udupi. 13. Upendra Pai Memorial College, Udupi 14. Milagres College, Kallianpur. 15. St. Mary’s Syrian College, Brahmavar. 16. Crossland College, Brahmavar 17. Sri Sharada College, Basrur. 18. Bhandarkar’s College, Kundapur. 19. S.V.S. College, Bantwal. 20. Vivekananda College, Puttur. 21. St. Philomena College, Puttur. 22. Govt. First Grade College, Uppinangady 23. Kukke Subrahmanyeshwara College, Subrahmanya 24. Sacred Heart College, Madanthyar 25. Sri Bhuvanendra College, Karkala. 26. Dr. N.S.A.M. First Grade College, Nitte 27.