Flag Tattoos: Markers of Class & Sexuality PROCEEDINGS Scot M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PWA Unity Diversity Publication July 2017

July 2017 Volume 1, Issue 3 Unity: Cultivating Diversity and Inclusion in PWA Hilo, Hawaii LGBT Film Screening Hilo, Hawaii recognized LGBT Month by holding a special screening of the film Limited Partnerships. Limited Partnership is the love story between Filipino-American Richard Adams and his Australian husband, Tony Sullivan. In 1975, thanks to a courageous county clerk in Boulder, CO, Richard and Tony were one of the first same-sex couples in the world to be legally married. Richard immediately filed for a green card for Tony based on their marriage. But unlike most heterosexual married couples who easily file petitions and obtain green cards, Richard received a denial letter from the Immi- gration and Naturalization Service stating, “You have failed to establish that a bona AREA DIRECTOR’S fide marital relationship can exist between two faggots.” Outraged at the tone, tenor CORNER: and politics of this letter and to prevent Tony’s impending deportation, the couple sued the U.S. government. This became the first federal lawsuit seeking equal treat- Maintaining a workplace that wel- ment for a same-sex marriage in U.S. history. comes diversity in all forms is an im- Over four decades of legal challenges, Richard and Tony figured out how to maintain portant component of attracting high- ly-qualified applicants for our job their sense of humor, justice and whenever possible, their privacy. Their personal vacancies. Celebrations of Special tale parallels the history of the LGBT marriage and immigration equality move- Emphasis Program months contribute ments, from the couple signing their marriage license in Colorado, to the historic to this effort by enhancing our appre- U.S. -

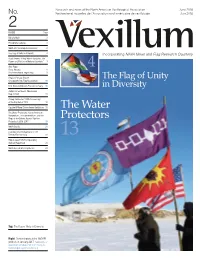

Vexillum, June 2018, No. 2

Research and news of the North American Vexillological Association June 2018 No. Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine de vexillologie Juin 2018 2 INSIDE Page Editor’s Note 2 President’s Column 3 NAVA Membership Anniversaries 3 The Flag of Unity in Diversity 4 Incorporating NAVA News and Flag Research Quarterly Book Review: "A Flag Worth Dying For: The Power and Politics of National Symbols" 7 New Flags: 4 Reno, Nevada 8 The International Vegan Flag 9 Regional Group Report: The Flag of Unity Chesapeake Bay Flag Association 10 Vexi-News Celebrates First Anniversary 10 in Diversity Judge Carlos Moore, Mississippi Flag Activist 11 Stamp Celebrates 200th Anniversary of the Flag Act of 1818 12 Captain William Driver Award Guidelines 12 The Water The Water Protectors: Native American Nationalism, Environmentalism, and the Flags of the Dakota Access Pipeline Protectors Protests of 2016–2017 13 NAVA Grants 21 Evolutionary Vexillography in the Twenty-First Century 21 13 Help Support NAVA's Upcoming Vatican Flags Book 23 NAVA Annual Meeting Notice 24 Top: The Flag of Unity in Diversity Right: Demonstrators at the NoDAPL protests in January 2017. Source: https:// www.indianz.com/News/2017/01/27/delay-in- nodapl-response-points-to-more.asp 2 | June 2018 • Vexillum No. 2 June / Juin 2018 Number 2 / Numéro 2 Editor's Note | Note de la rédaction Dear Reader: We hope you enjoyed the premiere issue of Vexillum. In addition to offering my thanks Research and news of the North American to the contributors and our fine layout designer Jonathan Lehmann, I owe a special note Vexillological Association / Recherche et nouvelles de l’Association nord-américaine of gratitude to NAVA members Peter Ansoff, Stan Contrades, Xing Fei, Ted Kaye, Pete de vexillologie. -

Commission Report Final UK

JOINT COMMISSION ON VEXILLOGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES of The Flag Institute and North American Vexillological Association ! ! THE COMMISSION’S REPORT ON THE GUIDING PRINCIPLES OF FLAG DESIGN 1st October 2014 These principles have been adopted by The Flag Institute and North American Vexillological Association | Association nord-américaine de vexillologie, based on the recommendations of a Joint Commission convened by Charles Ashburner (Chief Executive, The Flag Institute) and Hugh Brady (President, NAVA). The members of the Joint Commission were: Graham M.P. Bartram (Chairman) Edward B. Kaye Jason Saber Charles A. Spain Philip S. Tibbetts Introduction This report attempts to lay out for the public benefit some basic guidelines to help those developing new flags for their communities and organizations, or suggesting refinements to existing ones. Flags perform a very powerful function and this best practice advice is intended to help with optimising the ability of flags to fulfil this function. The principles contained within it are only guidelines, as for each “don’t do this” there is almost certainly a flag which does just that and yet works. An obvious example would be item 3.1 “fewer colours”, yet who would deny that both the flag of South Africa and the Gay Pride Flag work well, despite having six colours each. An important part of a flag is its aesthetic appeal, but as the the 18th century Scottish philosopher, David Hume, wrote, “Beauty in things exists merely in the mind which contemplates them.” Different cultures will prefer different aesthetics, so a general set of principles, such as this report, cannot hope to cover what will and will not work aesthetically. -

Agenda Format

NB-2 ADDITIONAL DOCUMENTS CITY POSITIONS ON STATE LEGISLATION CITY COUNCIL SUPPLEMENTAL REPORT MEETING DATE: MAY 7, 2019 SUBJECT: CITY POSITIONS ON STATE LEGISLATION: SCR 21 (CAPTAIN KREZA MEMORIAL HIGHWAY), SB 450 (MOTEL CONVERSIONS), AND AB 1273 (TOLL ROADS) (NB-2) DATE: MAY 6, 2019 FROM: CITY MANAGER’S OFFICE/ADMINISTRATION FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: CONNOR A. LOCK AT (714) 754-5219 The purpose of this supplemental report is to provide a correction to an attachment for New Business Item 2 ‘City Positions on State Legislation: SCR 21 (Captain Kreza Memorial Highway), SB 450 (Motel Conversions), and AB 1273 (Toll Roads)’. Attachment 1 contains an update to the Table of Bills for Consideration to reflect the appropriate requestor of Assembly Bill 1273. ALBERTO C. RUIZ Management Aide ATTACHMENTS: 1- Table of Bills for Consideration Attachment 1 – Table of Bills for Consideration 5/7/2019 Bill # Bill Requestor Requested League ACCOC Brief Summary Notable Notable Fiscal Author Position Position Position Supporters Opposition Impact (s) City Staff Recommendation: Support SCR Senators Fire Chief Support Watch No Senate Concurrent Resolution California None Unknown 21 Bates and Stefano Position 21 would honor Captain Kreza’s Professional Moorlach memory by dedicating a portion Firefighters of Interstate 5, from Avery Costa Mesa Parkway to El Toro, as the Costa Firefighters Mesa Fire Captain Michael Kreza Memorial Highway. SB Senator Mayor Support Watch No This bill would, until January 1, Mayors of: None Unknown 450 Umberg Foley Position 2025, exempt from CEQA, Anaheim projects related to the Bakersfield conversion of a structure with a Fresno certificate of occupancy as a Long Beach motel, hotel, apartment hotel, Los Angeles transient occupancy residential Oakland structure, or hostel to supportive Riverside housing or transitional housing, Sacramento as defined, that meet certain San Diego requirements. -

The Role of the United Nations in Combatting Discrimination and Violence Against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex People

The Role of the United Nations in Combatting Discrimination and Violence against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex People A Programmatic Overview 19 June 2018 This paper provides a snapshot of the work of a number of United Nations entities in combatting discrimination and violence based on sexual orientation, gender identity, sex characteristics and related work in support of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) and intersex communities around the world. It has been prepared by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights on the basis of inputs provided by relevant UN entities, and is not intended to be either exhaustive or detailed. Given the evolving nature of UN work in this field, it is likely to benefit from regular updating1. The final section, below, includes a Contact List of focal points in each UN entity, as well as links and references to documents, reports and other materials that can be consulted for further information. Click to jump to: Joint UN statement, OHCHR, UNDP, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UN Women, ILO, UNESCO, WHO, the World Bank, IOM, UNAIDS (the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS), UNRISD and Joint UN initiatives. Joint UN statement Joint UN statement on Ending violence and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people: o On 29 September 2015, 12 UN entities (ILO, OHCHR, UNAIDS Secretariat, UNDP, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNODC, UN Women, WFP and WHO) released an unprecedented joint statement calling for an end to violence and discrimination against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people. o The statement is a powerful call to action to States and other stakeholders to do more to protect individuals from violence, torture and ill-treatment, repeal discriminatory laws and protect individuals from discrimination, and an expression of the commitment on the part of UN entities to support Member States to do so. -

Sixty Morning Walks Andy Fitch

[Reading Copy Only: facsimile available at http://english.utah.edu/eclipse] Sixty Morning Walks Andy Fitch editions eclipse / 2008 Week One Tuesday 2.15 Before I pulled back the curtain I knew it was raining but then a sparrow called and I knew I’d been wrong. Bright clouds blew across the courtyard shaft. My New Balance had to stay stuffed with paper. My jeans had dried hung in the shower and didn’t even itch. Two women opened Dana Discovery Center. The one driving a golf cart in circles stopped. Silent attraction seemed to flow between us. The other smoked and rinsed rubber floormats. Wind made it cold for khaki ecologist suits. A cross-eyed girl shouted Morning! I couldn’t tell if there was someone behind me. On the way past I said Hello, twice, but she stared off gulping air. The pond at 110th (The Harlem Meer) is so reflective sometimes. Christo’s Gates had been up since Saturday. Last night I finally got to see them (in dismal circumstances: heavy bag, broken umbrella, damp socks and gloves). In all the Conservatory Gardens only one cluster of snowdrops had bloomed. Slender green shoots looked strong. Patchy light came through the trellis. As a jogger emitting techno beats curved beside the baseball fields I thought about vicarious emotional momentum. She had glossy dark hair. So many people use expensive hair products now. Somebody with leashes wrapped around one wrist sat with his face in a Daily News. People must always bug him about what it’s like to be a dog walker. -

Gloria Brame's Kinky Links Catalogue - General BDSM/Fetish Information

Gloria Brame's Kinky Links Catalogue - General BDSM/Fetish Information Please patronize the shops which fund this site. The Well-Read Head W.D. BRAME let a book kidnap your mind toys to torment and tease Kinky Links Index > General BDSM/Fetish Information Speaking the Kinky Lingo Gloria's comprehensive glossary of BDSM/fetish slang ● Albany Stocks and Bonds ● Leather Navigator A pansexual bdsm club dedicated to Excellent resource for leathermen and bears. providing members with information, education and a friendly environment to explore their interests and fantasies as related to BDSM. ● Alternate Resources Search Engine ● Lesbian Mailing Lists Search engine for kinky clubs, lodgings, A must for women who love women! newsgroups, more, worldwide. ● Aubrey's Playroom ● Links for Political Activists A 60 minute Internet talk show featuring Helpful resource for the politically inclined. conversation for the Leather, Fetish, BDSM, and Alternative Sexuality Communities. ● bianca's Smut Shack ● Moonkissed Pagan spirituality. http://gloria-brame.com/kinkylinks/generalbdsminfo.html (1 of 3) [4/1/2002 8:50:00 PM] Gloria Brame's Kinky Links Catalogue - General BDSM/Fetish Information ● BDSM Find ● My Dungeon of Links Features highlights from Usenet, an extensive linkdirectory, and free webmaster tools for BDSM websites, including the KinkPoll and personal forums ● Blacks/People of Color in BDSM ● Naughty Linx Resources Links to ton of adult-only sites. A Resource of information for People of Color in the BDSM community ● carmb's dungeon ● Night Sites articles, smutty stories, and links to BDSM Make your own free adult homepage. information ● Christian BDSM ● Queernet: Mailing Lists Exploring the Christian/BDSM world Great collection of mailing lists for g/l/b/tg and SM/fetish people. -

Flag Definitions

Flag Definitions Rainbow Flag : The rainbow flag, commonly known as the gay pride flag or LGBTQ pride flag, is a symbol of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer pride and LGBTQ social movements. Always has red at the top and violet at the bottom. It represents the diversity of gays and lesbians around the world. Bisexual Pride Flag: Bisexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behaviour toward both males and females, or to more than one sex or gender. Pink represents sexual attraction to the same sex only (gay and lesbian). Blue represents sexual attraction to the opposite sex only (Straight). Purple represents sexual attraction to both sexes (bi). The key to understanding the symbolism of the Bisexual flag is to know that the purple pixels of colour blend unnoticeably into both pink and blue, just as in the “real world” where bi people blend unnoticeably into both the gay/lesbian and straight communities. Transgender Pride Flag: Transgender people have a gender identity or gender expression that differs from their assigned sex. Blue stripes at top and bottom is the traditional colour for baby boys. Pink stipes next to them are the traditional colour for baby girls. White stripe in the middle is for people that are nonbinary, feel that they don’t have a gender. The pattern is such that no matter which way you fly it, it is always correct, signifying us finding correctness in our lives. Intersex Pride Flag: Intersex people are those who do not exhibit all the biological characteristics of male or female, or exhibit a combination of characteristics, at birth. -

11. Mummification: Let's Try

11. MUMMIFICATION: LET’S TRY IT! 1. What is the appeal of mummification for you? Both giving and receiving. RAHH Oh man. So, mummification is the ultimate in control. I have zero interest in receiving this- but giving it? Someone has to have a lot of trust in me - and I really like the feeling of someone trusting me to take care of them. Someone has to be cool with giving up total control - and I really like being in control. The other factor is that mummification gives you so much to build off of. Once someone is totally restrained, the scene is really your kinky oyster (Assuming you've negotiated any play after the mummification part!). STEPHANIEROSE12 For me, it's almost like objectification... It strips away one’s identity and movement. You're completely helpless and at another's mercy. TAYLORDAWNMODEL For me, I love the tightness and inability to move. It allows me to just mentally drift away and go to my happy place. I also love the feeling of being cut out of the wrap, it feels amazing when the air you’re your body. KNOT2NICE I love bondage for bondage sake. Mummification allows for such an extreme amount of immobility and is very quick. I like that from both sides of it. I like knowing that every movement in every direction is being impaired and that a sense of helplessness is surrounding the person being mummified. BEYOND_BOTTOM I can't speak for giving on this subject yet except to imagine creating the same feeling for someone that I enjoy receiving. -

THE RAINBOW FLAG of the INCAS by Gustav Tracchia

THE RAINBOW FLAG OF THE INCAS by Gustav Tracchia PROLOGUE: The people of this pre-Columbian culture that flourished in the mid- Andes region of South America (known as The Empire of The Incas) called their realm: Tawantinsuyo, meaning the four corners. The word INCA is Quechua for Lord or King and was attached to the name of the ruler e.g., Huascar Inca or Huayna Capac Inca. In Quechua, the official language of the empire; Suyo is corner and Tawa, number four. Ntin is the way to form the plural. Fig. 1 Map of the Tawantinsuyo Wikipedia, (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/file:inca expansion.png) 1 Gustav Tracchia The "four corners" or suyos radiated from the capital, Cuzco: - Chincasuyo: Northwest Peru, present day Ecuador and the tip of Southern Colombia. - Contisuyo: nearest to Cuzco, south-central within the area of modern Peru. - Antisuyo: almost as long as Chincansuyo but on the eastern side of the Andes, from northern Peru to parts of upper eastern Bolivia. - Collasuyo: Southwest: all of western Bolivia, northern Chile and northwest of Argentina. Fig. 2 Cobo, Historia, schematic division of the four suyos 2 The Rainbow Flag of the Incas Fig. 3 Map of Tawantinsuyo, overlapping present day South American political division. ()www.geocities.com/Tropics/beach/2523/maps/perutawan1.html To simplify, I am going to call this still mysterious pre-Columbian kingdom, not Tawantinsuyo, but the "Empire of the Incas" or "The Inca Empire." I am also going to refer to events related to the culture of the Incas as "Incasic" or "Incan". -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

BDSM Culture and Submissive-Role Women Lisa R

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2015 Liberation Through Domination: BDSM Culture and Submissive-Role Women Lisa R. Rivoli Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the Gender and Sexuality Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Rivoli, Lisa R., "Liberation Through Domination: BDSM Culture and Submissive-Role Women" (2015). Student Publications. 318. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/318 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 318 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Liberation Through Domination: BDSM Culture and Submissive-Role Women Abstract The alternative sexual practices of bondage and discipline, dominance and submission, and sadism and masochism (BDSM) are practiced by people all over the world. In this paper, I will examine the experiences of five submissive-role women in the Netherlands and five in south-central Pennsylvania, focusing specifically on how their involvement with the BDSM community and BDSM culture influences their self-perspective.I will begin my analysis by exploring anthropological perspectives of BDSM and their usefulness in studying sexual counterculture, followed by a consideration of feminist critiques of BDSM and societal barriers faced by women in the community.