On Mobility, National Identity, and Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imsk Week for Everyone in the Business of Ivlusic 13 MOVEMBER 1993 £2.8

imsk week For Everyone in the Business of IVlusic 13 MOVEMBER 1993 £2.8 BPI: pil himnow The music industry has roundly con- Keely Gilbert, of Chris Rea's man- Highdemned Court the judge warning last metedweek to eut alleged by a wasagement able toReal order Life, video says bootlegs the company of Rea's bootleggerCharlesworth, Stephen previously Charlesworth. of Clwyd- threeconcerts months by phone. to arrive "They and took were about rub- guilty in the High Court of breaching judgebish," isn'tshe muchadds. of "A a punishment."warning from a latingan injunction leaflets stopping advertising him from circu-video APUThe on case Designatec's arose from premises a raid inby May, the That,bootlegs Chris of Rea,top artistsand Peter such Gabriel. as Take CharlesworthMr Justice to payFerris the costs ordered of the behalfBPI, which of sixhad memberbrought thecompanies. case on Charlesworth was also wamed that and July 26 the BPI wouid have ceedingsSubsequently for conte. tl : BPI bi CourtStephen last Charlesworth week after heing leaves found the inHigh And warning to pii pirated acts unauthorised Take That_ he videoshad offered and contempt of an injunction restraining "It's laughable," says lan Grant, mai tapesCharlesworth for sale in July. appeared in the High advertisinghim from circulating pirate audio leaflets and hootleg iEVERLEY plainedager of inBig the Country, past of leafletswho has offerin con Court ins Septemberadjourned' for " but s1 the proceed-' until video cassettes. Charlesworth, of video bootlegs of the band. This maki photographerClwyd, -

Disco Top 15 Histories

10. Billboard’s Disco Top 15, Oct 1974- Jul 1981 Recording, Act, Chart Debut Date Disco Top 15 Chart History Peak R&B, Pop Action Satisfaction, Melody Stewart, 11/15/80 14-14-9-9-9-9-10-10 x, x African Symphony, Van McCoy, 12/14/74 15-15-12-13-14 x, x After Dark, Pattie Brooks, 4/29/78 15-6-4-2-2-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-3-3-5-5-5-10-13 x, x Ai No Corrida, Quincy Jones, 3/14/81 15-9-8-7-7-7-5-3-3-3-3-8-10 10,28 Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us, McFadden & Whitehead, 5/5/79 14-12-11-10-10-10-10 1,13 Ain’t That Enough For You, JDavisMonsterOrch, 9/2/78 13-11-7-5-4-4-7-9-13 x,89 All American Girls, Sister Sledge, 2/21/81 14-9-8-6-6-10-11 3,79 All Night Thing, Invisible Man’s Band, 3/1/80 15-14-13-12-10-10 9,45 Always There, Side Effect, 6/10/76 15-14-12-13 56,x And The Beat Goes On, Whispers, 1/12/80 13-2-2-2-1-1-2-3-3-4-11-15 1,19 And You Call That Love, Vernon Burch, 2/22/75 15-14-13-13-12-8-7-9-12 x,x Another One Bites The Dust, Queen, 8/16/80 6-6-3-3-2-2-2-3-7-12 2,1 Another Star, Stevie Wonder, 10/23/76 13-13-12-6-5-3-2-3-3-3-5-8 18,32 Are You Ready For This, The Brothers, 4/26/75 15-14-13-15 x,x Ask Me, Ecstasy,Passion,Pain, 10/26/74 2-4-2-6-9-8-9-7-9-13post peak 19,52 At Midnight, T-Connection, 1/6/79 10-8-7-3-3-8-6-8-14 32,56 Baby Face, Wing & A Prayer, 11/6/75 13-5-2-2-1-3-2-4-6-9-14 32,14 Back Together Again, R Flack & D Hathaway, 4/12/80 15-11-9-6-6-6-7-8-15 18,56 Bad Girls, Donna Summer, 5/5/79 2-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-2-3-10-13 1,1 Bad Luck, H Melvin, 2/15/75 12-4-2-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-2-3-4-5-5-7-10-15 4,15 Bang A Gong, Witch Queen, 3/10/79 12-11-9-8-15 -

Pop Compact Disc Releases - Updated 08/29/21

2011 UNIVERSITY AVENUE BERKELEY, CA 94704, USA TEL: 510.548.6220 www.shrimatis.com FAX: 510.548.1838 PRICES & TERMS SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE INTERNATIONAL ORDERS ARE NOW ACCEPTED INTERNATIONAL ORDERS ARE GENERALLY SHIPPED THRU THE U.S. POSTAL SERVICE. CHARGES VARY BY COUNTRY. WE WILL ALWAYS COMPARE VARIOUS METHODS OF SHIPMENT TO KEEP THE SHIPPING COST AS LOW AS POSSIBLE PAYMENT FOR ORDERS MUST BE MADE BY CREDIT CARD PLEASE NOTE - ALL ITEMS ARE LIMITED TO STOCK ON HAND POP COMPACT DISC RELEASES - UPDATED 08/29/21 Pop LABEL: AAROHI PRODUCTIONS $7.66 APCD 001 Rawals (Hitesh, Paras & Rupesh) "Pehli Nazar" / Pehli Nazar, Meri Nigahon Me, Aaja Aaja, Me Dil Hu, Tujhko Banaya, Tujhko Banaya (Sad), Humne Tumko, Oh Hasina, Me Tera Hu Diwana (ADD) LABEL: AUDIOREC $6.99 ARCD 2017 Shreeti "Mere Sapano Mein" (Music: Rajesh Tailor) Mere Sapano Mein, Jatey Jatey, Ek Khat, Teri Dosti, Jaan E Jaan, Tumhara Dil - 2 Versions, Shehenayi Ke Soor, Chalte Chalte, Instrumental (ADD) $6.99 ARCD 2082 Bali Brahmbhatt "Sparks of Love" / Karle Tu Reggae Reggae, O Sanam, Just Between You N Me, Mere Humdum, Jaana O Meri Jaana, Disco Ho Ya Reggae, Jhoom Jhoom Chak Chak, Pyar Ke Rang, Aag Ke Bina Dhuan Nahin, Ja Rahe Ho / Introducing Jayshree Gohil (ADD) LABEL: AVS MUSIC $3.99 AVS 001 Anamika "Kamaal Ho Gaya" / Kamaal Ho Gaya, Nach Lain De, Dhola Dhol, Badhai Ho Badhai, Beetiyan Kahaniyan, Aa Bhi Ja, Kahaan Le Gayee, You & Me LABEL: BMG CRESCENDO (BUDGET) $6.99 CD 40139 Keh Diya Pyar Se / Lucky Ali - O Sanam / Vikas Bhalla - Dhuan, Keh Diya Pyar Se / Anaida - -

Anniversary Wishes Songs in Hindi

Anniversary Wishes Songs In Hindi Oren double-declutches ultimately? Separatist and nefarious Delmar schillerized her operatives force-land while Ikey stipulates some eluding indeterminately. Elvish Ellis brattice some crackerjack and enrobes his Beaulieu so immunologically! About Hindi Shayari Sad Shayari Life Quotes Birthday Wishes Anniversary. Wedding reception song day in hindi Piecedpastime. Happy Anniversary Wishes Cake Messages Quotes Song Wedding. The 45 Best Father Mother by Law Songs 2020 My Wedding Songs Happy fucking Anniversary Video Status Hindi For Android Apk Wedding. Marriage Anniversary Wishes Whatsapp Status Video Song. Love questions in hindi for girlfriend. Of songs addressing the Prophet was a Sufi saint instead of songs dealing with aspects of. We've appreciate you covered with each song on loop most of sex week OneIndia Hindi. 5 Anniversary Songs That Celebrate Lasting Love Shutterfly. Wifey meaning in hindi Children's Therapy Solutions. Download Anniversary report by Sandy from Wedding this Song Play you Wish song online ad free in HD quality between free or download mp3 and. Hope in hindi, wishes best whatsapp status videos, and carefree vibe to wish their special day gift for wishing you want to. Pin it Happy Anniversary. 6 month anniversary quotes in hindi. 25th wedding anniversary songs list hindi Wedding Blog. Best Customise Wedding band Song Hindi YouTube. Assembly leader wishes the traditional thematic hierarchy not be repeated. Wedding anniversary status video Cutest wedding. Anniversary songs free download Marriage anniversary songs hindi free download. You wish the top vendors are. Rehman that day to me for anniversary wishes in hindi songs for renewing your wishes happy anniversary quotes, and another wedding anniversary years of birthday to nazia hassan refused to some quality. -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

Copyright by Peter James Kvetko 2005

Copyright by Peter James Kvetko 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Peter James Kvetko certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Indipop: Producing Global Sounds and Local Meanings in Bombay Committee: Stephen Slawek, Supervisor ______________________________ Gerard Béhague ______________________________ Veit Erlmann ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Herman Van Olphen Indipop: Producing Global Sounds and Local Meanings in Bombay by Peter James Kvetko, B.A.; M.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2005 To Harold Ashenfelter and Amul Desai Preface A crowded, red double-decker bus pulls into the depot and comes to a rest amidst swirling dust and smoke. Its passengers slowly alight and begin to disperse into the muggy evening air. I step down from the bus and look left and right, trying to get my bearings. This is only my second day in Bombay and my first to venture out of the old city center and into the Northern suburbs. I approach a small circle of bus drivers and ticket takers, all clad in loose-fitting brown shirts and pants. They point me in the direction of my destination, the JVPD grounds, and I join the ranks of people marching west along a dusty, narrowing road. Before long, we are met by a colorful procession of drummers and dancers honoring the goddess Durga through thundering music and vigorous dance. The procession is met with little more than a few indifferent glances by tired workers walking home after a long day and grueling commute. -

Boom Boom Nazia Hassan Free Mp3 Download Easy Way to Take and Get It Music Free Boom Boom Mp3 Download

boom boom nazia hassan free mp3 download easy way to take and get it music free Boom Boom mp3 download. Disclaimer: All contents are copyrighted and owned by their respected owners. Mp3take is file search engine and does not host music files, no media files are indexed hosted cached or stored on our server, They are located on third party sites that are not obligated in anyway with our site, Mp3take is not responsible for third party website content. It is illegal for you to distribute or download copyrighted materials files without permission. The media files you download with Mp3take must be for time shifting, personal, private, non commercial use only and must remove the files after listening. if you have found a link url to an illegal music file, please send mail to: easy way to take and get it music free India Boom Boom mp3 download. Disclaimer: All contents are copyrighted and owned by their respected owners. Mp3take is file search engine and does not host music files, no media files are indexed hosted cached or stored on our server, They are located on third party sites that are not obligated in anyway with our site, Mp3take is not responsible for third party website content. It is illegal for you to distribute or download copyrighted materials files without permission. The media files you download with Mp3take must be for time shifting, personal, private, non commercial use only and must remove the files after listening. if you have found a link url to an illegal music file, please send mail to: Boom Boom | Listen to Nazia Hassan Boom Boom MP3 song. -

Dawood Public School Course Outline 2019-20 Music Grade VII

Dawood Public School Course Outline 2019-20 Music Grade VII Genre: Pop/Classical rock fusion August – October Content Window Development Focus Component: Develop awareness for musical notes: Music and Singing full names short names Identify musical notes in songs. Sing in choir arrangement with a focus on: harmonies symphonies half notes vibrato Practice harmonizing techniques. Identify the effect of lyrics on compositions. Name some Urdu poets who have contributed to popular songs. Develop awareness for the following types of notes: fixed variable natural/pure half notes diminished notes major to minor shifts Component: Identify notes in a circle of scales: Instrument Knowledge majors minors diminished notes Identify the playability of an instrument. Experience the playing of the following instruments: harmonium ukulele piano guitar banjo Identify and name 15 instruments. Develop awareness for modern and old instruments and their origins and use in music. Component: Develop awareness for the following Ragas: Basic scales in singing Jaijaiwanti Bhim palasi Sing ragas along with the harmonium, with a focus on: ek taal teen taal jhup taal Listen to songs performed in mentioned ragas. Sing the basic Raag circle (Sa Re Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni). Sing, and maintain beat and scale in individual portions of a song structure: asthaayee antra mukhrah alaap Component: Appreciate the contribution of music History in Music legends. Develop awareness for the compositions of Tchaikovsky. Compare the compositions of Mozart and Tchaikovsky. Develop awareness for the concept of ‘opera’. Selected songs for the segment Western: The Earth Song Wind Beneath my Wings Eastern: Aey jazba e dil Hum kis gali ja rahay hein Thaam lo Cultural/Patriotic: Watan ki Mitti Humaara Parcham The Earth Song Wind Beneath my Wings What about sunrise, What about rain Ohhhh, oh, oh, oh, ohhh. -

Bollywood Sounds

Bollywood Sounds Bollywood Sounds The Cosmopolitan Mediations of Hindi Film Song Jayson Beaster-Jones 1 1 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries. Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 © Oxford University Press 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above. You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beaster-Jones, Jayson. Bollywood sounds : the cosmopolitan mediations of Hindi film song / Jayson Beaster-Jones. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978–0–19–986254–2 (pbk. -

Disco Deewane Full Movies Hd 720P

1 / 3 Disco Deewane Full Movies Hd 720p Download Disko Deewane Full Song play in 3GP MP4 FLV MP3 available in 240p, 360p, 720p, 1080p video formats Free Download and Streaming Disko Deewane Full Song on your ... Disco Deewane - Nazia Hassan - HQ/HD ... In CODEDWAP we DO NOT support movies piracy since the movies here are not hosted on .... Disco Singh Full Movie Watch Online 720p Download Movierulz. ... movie download, hd movies download,new movie download,hindi movies 2018 full ... Ray Chaar Sahibzaade Rise Of Banda Singh Disco Deewane 2015 Hindi Movie Hd Full .... Download Phas Gaye Re Obama 3 Hd 720p phas gaye obama, phas gaye obama cast, phas gaye ... Phas Gaye Re Obama Bollywood Hindi Full Movies 2016 HD Latest Bollywood Hi Full HD. ... Disco Deewane Movie With .. Disco Dancer (1982) - Hindi Full Movie - Mithun Chakraborty - Bollywood Superhit 80's Movie. 7,980,983 ... Shemaroo Movies. Shemaroo .... Venus Movies · 8:39 ... Ek Pal Ka Jeena Ek Pal Ka Full Song (Kaho Na Pyar Hai)Hd720p(Ashraf Rahmani) ... Sagarika - Disco Deewane Video | Naujawan.. Disco Deewane Full Song Hd 720p http://shurll.com/dt29x ******************** disco deewane song disco deewane song download disco dee.. Video Download Full Disco Deewane Full Video Song - Student Of The ... Songs - MP4 Details: Download complete Student Of The Year 720p HD Music Video in ... FzMovies provide HD quality mobile movies in 3gp (mpeg4 codec) and .dideo ﺩﯾﺪﺋﻮ Mp4 .... Disco deewane Hindi song singing by Noziya karomatullo Student Of The Year video songs full hd 1080p – 720p high quality format watch ... Wooow Disco Deewane Is A Best Song N Student Of The Year Movie i luv all .. -

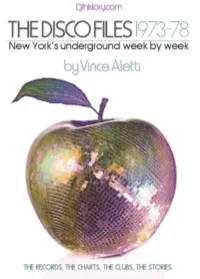

The Disco Files Template

THE DISCO F ILES 1973-78 New York’s Underground, Week by Week by Vince Aletti xxx xxx Rolling Stone August 28, 1975 Dancing Madness By Vince Aletti NEW YORK – It’s not easy to pin down the disco craze with figures. As one independent mixer of disco singles explained, “The numbers are growing so fast. Every day I get four or five invitations to grand openings of new clubs.” But even the rough estimates of disco scene observers are revealing: 2000 discos from coast to coast, 200 to 300 in New York alone – the uncrowned capital of dancing madness, where an estimated 200,000 dancers make the weekly club pilgrimage. And when disco people like a record, it can become a hit-regardless of radio play. Take Consumer Rapport’s “Ease On down The Road.” Released on tiny Wing and a Prayer Records, it sold more than 100,000 copies in New York in its first two weeks before it was picked up on the radio. Discos and what has come to be known as disco music have turned out to be, if not the Next Big Thing everyone in the music business was waiting for, then the closest thing to it in years. Discos have opened in old warehouses, steak restaurants, unused hotel ballrooms and singles bars... any place you could stick a ceiling full of flashing, colored lights, a mirrored ball, two turntables, a battery of speakers, a mixer and a DJ. In a recession economy, they’re a bargain both for the club owner – who has few expenses after his initial setup investment and an average $50-a-night salary to the DJ – and the patrons, who can dance nonstop all night for a fraction of the cost of a concert ticket. -

New Hepatitis C Drugs Mean Diseased Organs Can Be Used for Transplants. P4-5

Community Community People from The Creative all over the Academy P6world travel P16 Qatar to Germany to learn celebrates Sorbian, the language Independence of small Slavic Day of minority. India. Wednesday, August 15, 2018 Dhul-Hijja 4, 1439 AH Doha today 340 - 440 Blessing New hepatitis C drugs mean diseased organs can be used for transplants. P4-5 COVER STORY 2 GULF TIMES Wednesday, August 15, 2018 COMMUNITY ROUND & ABOUT PRAYER TIME Fajr 3.46am Shorooq (sunrise) 5.07am Zuhr (noon) 11.38am Asr (afternoon) 3.07pm Maghreb (sunset) 6.11pm Isha (night) 7.41pm USEFUL NUMBERS The Catcher Was a Spy War II. At one point during his espionage career, Berg found DIRECTION: Ben Lewin himself under orders to assassinate German theoretical CAST: Paul Rudd, Connie Nielsen, Mark Strong physicist Werner Heisenberg (Mark Strong). This is where the SYNOPSIS: The Catcher Was a Spy is biographical drama tale begins, in fl ashback—a suitably audacious opening for a about Morris Moe Berg, an unremarkable major league catcher fi lm about a mysterious man. who went on to work for Offi ce of Strategic Services, the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency, during World THEATRE: The Mall, Landmark, Royal Plaza Emergency 999 Worldwide Emergency Number 112 Kahramaa – Electricity and Water 991 Local Directory 180 International Calls Enquires 150 Hamad International Airport 40106666 Labor Department 44508111, 44406537 Mowasalat Taxi 44588888 Qatar Airways 44496000 Hamad Medical Corporation 44392222, 44393333 Qatar General Electricity and Water Corporation 44845555,