Independent Development of Lymphoid and Histiocytic Malignancies from a Shared Early Precursor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

Identification of a Receptor Required for the Anti-Inflammatory Activity of IVIG

Identification of a receptor required for the INAUGURAL ARTICLE anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG Robert M. Anthonya, Fredrik Wermelinga,b, Mikael C. I. Karlssonb, and Jeffrey V. Ravetcha,1 aThe Laboratory of Molecular Genetics and Immunology, The Rockefeller University, New York, NY 10065; and bDepartment of Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, 171 76 Stockholm, Sweden This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected on April 25, 2006. Contributed by Jeffrey V. Ravetch, October 11, 2008 (sent for review October 1, 2008) The anti-inflammatory activity of intravenous Ig (IVIG) results from patients suffering from autoimmune diseases (3). Monomeric IgG, a minor population of the pooled IgG molecules that contains purified from the serum of thousands of healthy donors (IVIG) is terminal ␣2,6-sialic acid linkages on their Fc-linked glycans. These a commonly administered at high doses (1–2 g/kg) for the treatment anti-inflammatory properties can be recapitulated with a fully of a number of autoimmune diseases, including immune-mediated recombinant preparation of appropriately sialylated IgG Fc frag- thrombocytopenia, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneu- ments. We now demonstrate that these sialylated Fcs require a ropathy, Kawasaki Disease and Guillain-Barre syndrome, and is specific C-type lectin, SIGN-R1, (specific ICAM-3 grabbing non- widely used in other autoimmune disorders (4–6). integrin-related 1) expressed on macrophages in the splenic mar- A number of hypotheses have been advanced to explain the ginal zone. Splenectomy, loss of SIGN-R1؉ cells in the splenic paradoxical activity of high dose IgG, and include models that marginal zone, blockade of the carbohydrate recognition domain attribute the activity to the polyclonal binding specificities, encoded (CRD) of SIGN-R1, or genetic deletion of SIGN-R1 abrogated the in the variable domains of the administered antibodies that may anti-inflammatory activity of IVIG or sialylated Fc fragments. -

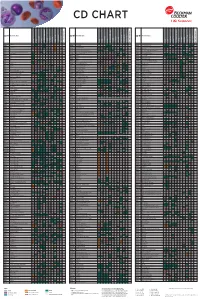

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

Chapter 6.4 Herpes Simplex Virus Enhances HIV-1 Transmission By

6.4: HSV enhances HIV-1 transmission by LCs Chapter 6.4 Herpes simplex virus enhances HIV-1 transmission by Langerhans cells. Lot de Witte*, Marein A.W.P. de Jong*, Yvette van Kooyk and Teunis B.H. Geijtenbeek. Genital herpes is a risk factor to acquire HIV-1 infection by sexual contact, by increasing both infectivity of an infected person and susceptibility to acquire HIV-1. Here we have investigated the mechanisms that underlie the increased susceptibility to HIV-1 when people have genital herpes. Under steady state conditions, LCs capture HIV-1 through interaction with the C-type lectin Langerin, resulting in viral clearance and protection against HIV-1. During primary genital herpes or recurrent infections, HSV infects epithelial cells and encounters LCs in the mucosal epithelium. We set out to investigate the function of HSV-infected LCs and subepithelial DCs during HIV-1 transmission. We demonstrate that HSV interacts with soluble and cellular Langerin and that infection of LCs decreases expression of this receptor. Notably, LC infection with both HSV-1 and HSV-2 enhances HIV-1 transmission, suggesting an important role for LCs during HIV-1 transmission in the HSV-infected individual. Furthermore our data indicate that HSV infection of DCs and LCs has different outcomes for HIV-1 transmission, and our results suggest that DC-SIGN and Langerin are involved. Future research is needed to confirm the differential role of Langerin and DC-SIGN during HIV-1 transmission in conditions of genital herpes. Department of Molecular Cell Biology and Immunology, VU University Medical Center, van der Boechorststraat 7, 1081 BT, Amsterdam, The Netherlands *Authors contributed equally to this work (Manuscript submitted for publication) 195 Section 6: Risk factors to acquire HIV-1: a role for Langerhans cells? Introduction Genital herpes is a common infection, which is mainly caused by herpes simplex virus type-2 (HSV-2), although an increasing percentage of the genital herpes is caused by HSV-141. -

The Chemokine System in Innate Immunity

Downloaded from http://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/ on September 28, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press The Chemokine System in Innate Immunity Caroline L. Sokol and Andrew D. Luster Center for Immunology & Inflammatory Diseases, Division of Rheumatology, Allergy and Immunology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02114 Correspondence: [email protected] Chemokines are chemotactic cytokines that control the migration and positioning of immune cells in tissues and are critical for the function of the innate immune system. Chemokines control the release of innate immune cells from the bone marrow during homeostasis as well as in response to infection and inflammation. Theyalso recruit innate immune effectors out of the circulation and into the tissue where, in collaboration with other chemoattractants, they guide these cells to the very sites of tissue injury. Chemokine function is also critical for the positioning of innate immune sentinels in peripheral tissue and then, following innate immune activation, guiding these activated cells to the draining lymph node to initiate and imprint an adaptive immune response. In this review, we will highlight recent advances in understanding how chemokine function regulates the movement and positioning of innate immune cells at homeostasis and in response to acute inflammation, and then we will review how chemokine-mediated innate immune cell trafficking plays an essential role in linking the innate and adaptive immune responses. hemokines are chemotactic cytokines that with emphasis placed on its role in the innate Ccontrol cell migration and cell positioning immune system. throughout development, homeostasis, and in- flammation. The immune system, which is de- pendent on the coordinated migration of cells, CHEMOKINES AND CHEMOKINE RECEPTORS is particularly dependent on chemokines for its function. -

Insights Into Interactions of Mycobacteria with the Host Innate

This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the author and source are cited. Articles pubs.acs.org/acschemicalbiology Insights into Interactions of Mycobacteria with the Host Innate Immune System from a Novel Array of Synthetic Mycobacterial Glycans † ‡ † † † † Ruixiang Blake Zheng, Sabine A. F. Jegouzo,́ Maju Joe, Yu Bai, Huu-Anh Tran, Ke Shen, † † † † § § Jörn Saupe, Li Xia, Md. Faiaz Ahmed, Yu-Hsuan Liu, Pratap Subhashrao Patil, Ashish Tripathi, § ‡ † ‡ Shang-Cheng Hung, Maureen E. Taylor,*, Todd L. Lowary,*, and Kurt Drickamer*, † Department of Chemistry and Alberta Glycomics Centre, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2G2, Canada ‡ Department of Life Sciences, Imperial College, London SW7 2AZ, United Kingdom § Genomics Research Centre, Academia Sinica, Nangang, Taipei 11529, Taiwan *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: An array of homogeneous glycans representing all the major carbohydrate structures present in the cell wall of the human pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other mycobacteria has been probed with a panel of glycan-binding receptors expressed on cells of the mammalian innate immune system. The results provide an overview of interactions between mycobacterial glycans and receptors that mediate uptake and survival in macrophages, dendritic cells, and sinusoidal endothelial cells. A subset of the wide variety of glycan structures present on mycobacterial surfaces interact with cells of the innate immune system through the receptors tested. Endocytic receptors, including the mannose receptor, DC-SIGN, langerin, and DC-SIGNR (L-SIGN), interact predominantly with mannose-containing caps found on the mycobacterial polysaccharide lipoarabinomannan. Some of these receptors also interact with phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides and mannose-containing phenolic glycolipids. -

The Role of Langerin Transfer From

Inhibition of Two Temporal Phases of HIV-1 Transfer from Primary Langerhans Cells to T Cells: The Role of Langerin This information is current as Najla Nasr, Joey Lai, Rachel A. Botting, Sarah K. Mercier, of September 29, 2021. Andrew N. Harman, Min Kim, Stuart Turville, Rob J. Center, Teresa Domagala, Paul R. Gorry, Norman Olbourne and Anthony L. Cunningham J Immunol 2014; 193:2554-2564; Prepublished online 28 July 2014; Downloaded from doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400630 http://www.jimmunol.org/content/193/5/2554 Supplementary http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2014/07/26/jimmunol.140063 http://www.jimmunol.org/ Material 0.DCSupplemental References This article cites 60 articles, 30 of which you can access for free at: http://www.jimmunol.org/content/193/5/2554.full#ref-list-1 Why The JI? Submit online. by guest on September 29, 2021 • Rapid Reviews! 30 days* from submission to initial decision • No Triage! Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists • Fast Publication! 4 weeks from acceptance to publication *average Subscription Information about subscribing to The Journal of Immunology is online at: http://jimmunol.org/subscription Permissions Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html Email Alerts Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts The Journal of Immunology is published twice each month by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2014 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. -

Human Lectins, Their Carbohydrate Affinities and Where to Find Them

biomolecules Review Human Lectins, Their Carbohydrate Affinities and Where to Review HumanFind Them Lectins, Their Carbohydrate Affinities and Where to FindCláudia ThemD. Raposo 1,*, André B. Canelas 2 and M. Teresa Barros 1 1, 2 1 Cláudia D. Raposo * , Andr1 é LAQVB. Canelas‐Requimte,and Department M. Teresa of Chemistry, Barros NOVA School of Science and Technology, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, 2829‐516 Caparica, Portugal; [email protected] 12 GlanbiaLAQV-Requimte,‐AgriChemWhey, Department Lisheen of Chemistry, Mine, Killoran, NOVA Moyne, School E41 of ScienceR622 Co. and Tipperary, Technology, Ireland; canelas‐ [email protected] NOVA de Lisboa, 2829-516 Caparica, Portugal; [email protected] 2* Correspondence:Glanbia-AgriChemWhey, [email protected]; Lisheen Mine, Tel.: Killoran, +351‐212948550 Moyne, E41 R622 Tipperary, Ireland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-212948550 Abstract: Lectins are a class of proteins responsible for several biological roles such as cell‐cell in‐ Abstract:teractions,Lectins signaling are pathways, a class of and proteins several responsible innate immune for several responses biological against roles pathogens. such as Since cell-cell lec‐ interactions,tins are able signalingto bind to pathways, carbohydrates, and several they can innate be a immuneviable target responses for targeted against drug pathogens. delivery Since sys‐ lectinstems. In are fact, able several to bind lectins to carbohydrates, were approved they by canFood be and a viable Drug targetAdministration for targeted for drugthat purpose. delivery systems.Information In fact, about several specific lectins carbohydrate were approved recognition by Food by andlectin Drug receptors Administration was gathered for that herein, purpose. plus Informationthe specific organs about specific where those carbohydrate lectins can recognition be found by within lectin the receptors human was body. -

C-Type Lectins in Veterinary Species: Recent Advancements and Applications

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review C-Type Lectins in Veterinary Species: Recent Advancements and Applications Dimitri Leonid Lindenwald and Bernd Lepenies * Immunology Unit & Research Center for Emerging Infections and Zoonoses (RIZ), University for Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Foundation, 30559 Hannover, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-(0)5-11/953-6135 Received: 29 June 2020; Accepted: 17 July 2020; Published: 20 July 2020 Abstract: C-type lectins (CTLs), a superfamily of glycan-binding receptors, play a pivotal role in the host defense against pathogens and the maintenance of immune homeostasis of higher animals and humans. CTLs in innate immunity serve as pattern recognition receptors and often bind to glycan structures in damage- and pathogen-associated molecular patterns. While CTLs are found throughout the whole animal kingdom, their ligand specificities and downstream signaling have mainly been studied in humans and in model organisms such as mice. In this review, recent advancements in CTL research in veterinary species as well as potential applications of CTL targeting in veterinary medicine are outlined. Keywords: C-type lectin; glycans; immune modulation; comparative immunology; veterinary immunology 1. Introduction Glycans belong to the most abundant macromolecules constituting all living organisms. In multicellular animals, processes such as cell migration, homeostasis maintenance, and innate immune signaling rely on the ability of cells to recognize glycoconjugates, most often in the form of glycoproteins and glycolipids, via glycan binding proteins, the so-called lectins [1]. In the immune system, lectin receptors are either secreted or found on the cell surface of immune cells [2]. -

View Board of FITC (BD Biosciences), CD123-PE (Biolegend), Cd11c-APC Baylor Research Institute (Dallas, TX, USA)

Duluc et al. Genome Medicine 2014, 6:98 http://genomemedicine.com/content/6/11/98 RESEARCH Open Access Transcriptional fingerprints of antigen-presenting cell subsets in the human vaginal mucosa and skin reflect tissue-specific immune microenvironments Dorothée Duluc1†, Romain Banchereau1†, Julien Gannevat1, Luann Thompson-Snipes1, Jean-Philippe Blanck1, Sandra Zurawski1, Gerard Zurawski1, Seunghee Hong1, Jose Rossello-Urgell1, Virginia Pascual1, Nicole Baldwin1, Jack Stecher2, Michael Carley2, Muriel Boreham2 and SangKon Oh1* Abstract Background: Dendritic cells localize throughout the body, where they can sense and capture invading pathogens to induce protective immunity. Hence, harnessing the biology of tissue-resident dendritic cells is fundamental for the rational design of vaccines against pathogens. Methods: Herein, we characterized the transcriptomes of four antigen-presenting cell subsets from the human vagina (Langerhans cells, CD14- and CD14+ dendritic cells, macrophages) by microarray, at both the transcript and network level, and compared them to those of three skin dendritic cell subsets and blood myeloid dendritic cells. Results: We found that genomic fingerprints of antigen-presenting cells are significantly influenced by the tissue of origin as well as by individual subsets. Nonetheless, CD14+ populations from both vagina and skin are geared towards innate immunity and pro-inflammatory responses, whereas CD14- populations, particularly skin and vaginal Langerhans cells, and vaginal CD14- dendritic cells, display both Th2-inducing and regulatory phenotypes. We also identified new phenotypic and functional biomarkers of vaginal antigen-presenting cell subsets. Conclusions: We provide a transcriptional database of 87 microarray samples spanning eight antigen-presenting cell populations in the human vagina, skin and blood. Altogether, these data provide molecular information that will further help characterize human tissue antigen-presenting cell lineages and their functions. -

Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 Bdbiosciences.Com/Cdmarkers

BD Biosciences Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 bdbiosciences.com/cdmarkers 23-12399-01 CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD1a R4, T6, Leu6, HTA1 b-2-Microglobulin, CD74 + + + – + – – – CD93 C1QR1,C1qRP, MXRA4, C1qR(P), Dj737e23.1, GR11 – – – – – + + – – + – CD220 Insulin receptor (INSR), IR Insulin, IGF-2 + + + + + + + + + Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), IGF-1R, type I IGF receptor (IGF-IR), CD1b R1, T6m Leu6 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD94 KLRD1, Kp43 HLA class I, NKG2-A, p39 + – + – – – – – – CD221 Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I), IGF-II, Insulin JTK13 + + + + + + + + + CD1c M241, R7, T6, Leu6, BDCA1 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD178, FASLG, APO-1, FAS, TNFRSF6, CD95L, APT1LG1, APT1, FAS1, FASTM, CD95 CD178 (Fas ligand) + + + + + – – IGF-II, TGF-b latency-associated peptide (LAP), Proliferin, Prorenin, Plasminogen, ALPS1A, TNFSF6, FASL Cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6P-R, CIM6PR, CIMPR, CI- CD1d R3G1, R3 b-2-Microglobulin, MHC II CD222 Leukemia -

The Antigen Presenting Cells Instruct Plasma Cell Differentiation

REVIEW ARTICLE published: 06 January 2014 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00504 The antigen presenting cells instruct plasma cell differentiation Wei Xu 1* and Jacques Banchereau 2 1 Pharma Research and Early Development, F.Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Roche Glycart AG, Schlieren, Switzerland 2 The Jackson Laboratory, Institute for Genomic Medicine, Farmington, CT, USA Edited by: The professional antigen presenting cells (APCs), including many subsets of dendritic cells Catherine Pellat-Deceunynck, Centre and macrophages, not only mediate prompt but non-specific response against microbes, National de la Recherche Scientifique, but also bridge the antigen-specific adaptive immune response through antigen presen- France tation. In the latter, typically activated B cells acquire cognate signals from T helper cells Reviewed by: Laurence Morel, University of Florida, in the germinal center of lymphoid follicles to differentiate into plasma cells (PCs), which USA generate protective antibodies. Recent advances have revealed that many APC subsets Paulo Vieira, Institut Pasteur de Paris, provide not only “signal 1” (the antigen), but also “signal 2” to directly instruct the dif- France Gaetan Jego, University of Burgundy, ferentiation process of PCs in a T-cell-independent manner. Herein, the different signals France provided by these APC subsets to direct B cell proliferation, survival, class switching, and *Correspondence: terminal differentiation are discussed. We furthermore propose that the next generation of Wei Xu, Human Immunology Unit, vaccines for boosting antibody response could be designed by targeting APCs. Pharma Research and Early Development, Hoffmann-La Roche Keywords: plasma cells, antigen presenting cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, B cells Ltd., Roche Glycart AG, Wagistrasse 18, Schlieren 8952, Switzerland e-mail: [email protected] INTRODUCTION provided by these APC subsets and shapes a rationale of designing B cell activation is initiated following engagement of the B cell therapeutic vaccines for humoral immunity by targeting APCs.