Black Feminism in Frances EW Harper's “Vashti”&A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Take A'trip' to the Gallery —Page 4

I . & i • 4 « Ehra Hau, bronze modalM In Taa Kwon Do In tha 1988 Olymplca, delivers a aplnning back kick to Jaime Myatic during a regular training exerolaa of the American Taa Kwon Do Academy. Take a'trip' to the gallery —page 4 Vice Pres. 'Top' of shake-up the charts -page 2 —page6 NEWS New title, duties added to academic affairs VP After a restmctimng of upper serving as assistant to the interim Provost. level administration at UTSA, However, when a permanent provost is the position of vice president found, Val verde'sconlractis not expected for academic affairs has been tobe renewed. Valverde's offke was con tacted for more informadon, but no mes renamed and expanded. The sages were returned. new position, provost and vice- Dr. Linda Whitson, vice preskknt for president for academic afTairs, administration and planning, was also VP tor academic alMra and now pravoat until a permanent pn>- aaaiata the Interim provoat. voat la appointed. (of Dr. Valverde). Valvenk demotkm. DeLuna said that the Ttie provost position erjcompasses tiie duties of ttie She has no historical knowledge cm the group does not wish to speak to the media subject, and cannot verify or comment on about dwir plans. When adced why she vice president for academic affairs while increasing itsany artkk addressing the subject of Dr. sakl, "Sdategy, I guess." Valvenk." The provost position encompasses the scope of auttiority. Ttie Provost will serve as acting Dr. James W. Wagener, professor in duties of the vice president for academic tlw division of education and presitknt of affairs whik increasing its scope of au UTSA when Valverde was hired, was thority. -

Collective Memory and the Constructio

Liljedahl: Recalling the (Afro)Future: Collective Memory and the Constructio RECALLING THE (AFRO)FUTURE: COLLECTIVE MEMORY AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF SUBVERSIVE MEANINGS IN JANELLE MONÁE’S METROPOLIS-SUITES Everywhere, the “street” is considered the ground and guarantee of all reality, a compulsory logic explaining all Black Music, conveniently mishearing antisocial surrealism as social realism. Here sound is unglued from such obligations, until it eludes all social responsibility, thereby accentuating its unreality principle. (Eshun 1998: -41) When we listen to music in a non-live setting, we do so via some form of audio reproduction technology. To most listeners, the significant part about the technology is not the technology itself but the data (music) it stores and reverberates into our ears (Sofia 2000). Most of these listeners have memories tied to their favourite songs (DeNora 2000) but if the music is at the centre of the history of a people, can the songs themselves be seen as a form of recollection? In this paper, I suggest that sound reproduction technology can be read as a storage of memories in the context of Black American popular music. I will turn my attention to the critical potential of Afrofuturist narratives in the field of memory- technology in order to focus on how collective memory is performed as Afrofuturist technology in Black American popular music, specifically in the music of Janelle Monáe. At play in the theoretical backdrop of this article are two key concepts: Signifyin(g) and collective memory, the first of which I will describe in simplified terms, while the latter warrants a more thorough discussion. -

25Th Super Bock Super Rock

25th Super Bock Super Rock New line-up announcement: Janelle Monáe July 20, Super Bock Stage July 18, 19, 20 Herdade do Cabeço da Flauta, Meco - Sesimbra superbocksuperrock.pt | facebook.com/sbsr | instagram.com/superbocksuperrock After the line up confirmations of Lana Del Rey, Cat Power, Charlotte Gainsbourg and Christine and The Queens, there’s another feminine talent on her way to Super Bock Super Rock: the North American Grammy-nominated, singer, songwriter, arranger and producer Janelle Monáe, performs on July 20 at the Super Bock Stage. JANELLE MONÁE Janelle Monáe Robinson was born and raised in Kansas City but soon felt the need to go in search of her dreams and headed out to New York. She enrolled in the American Musical and Dramatic Academy and at the time, her goal was to make musicals. Life ended up givigin Janelle some other possibilities and shortly thereafter, she began to participate in several songs by Outkast, having been invited by Big Boi. She began to appear under the spotlight thanks to her enormous talent, being a multifaceted and very focused artist. She released her first EP in 2007, “Metropolis: Suite I (The Chase)”. These first songs caught the producer Diddy’s eyes (Sean “Puffy” Combs) who soon hired Janelle for his label, Bad BoY Records. Her first Grammy nomination came at this time with the single “Many Moons”. Three years later, in 2010, Monae released her debut album. “The ArchAndroid” was inspired by the German film “Metropolis”, which portrays a futuristic world, a dystopian projection of humanity. The album’s whole concept raised some ethical issues and enriched the songs, these authentic pop pearls, filled with soul and funk. -

Agency in the Afrofuturist Ontologies of Erykah Badu and Janelle Monáe

Open Cultural Studies 2018; 2: 330–340 Research Article Nathalie Aghoro* Agency in the Afrofuturist Ontologies of Erykah Badu and Janelle Monáe https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2018-0030 Received May 21, 2018; accepted September 26, 2018 Abstract: This article discusses the visual, textual, and musical aesthetics of selected concept albums (Vinyl/CD) by Afrofuturist musicians Erykah Badu and Janelle Monaé. It explores how the artists design alternate projections of world/subject relations through the development of artistic personas with speculative background narratives and the fictional emplacement of their music within alternate cultural imaginaries. It seeks to establish that both Erykah Badu and Janelle Monáe use the concept album as a platform to constitute their Afrofuturist artistic personas as fluid black female agents who are continuously in the process of becoming, evolving, and changing. They reinscribe instances of othering and exclusion by associating these with science fiction tropes of extraterrestrial, alien lives to express topical sociocultural criticism and promote social change in the context of contemporary U.S. American politics and black diasporic experience. Keywords: conceptual art, Afrofuturism, gender performance, black music, artistic persona We come in peace, but we mean business. (Janelle Monáe) In her Time’s up speech at the Grammys in January 2018, singer, songwriter, and actress Janelle Monáe sends out an assertive message from women to the music industry and the world in general. She repurposes the ambivalent first encounter trope “we come in peace” by turning it into a manifest for a present-day feminist movement. Merging futuristic, utopian ideas with contemporary political concerns pervades Monáe’s public appearances as much as it runs like a thread through her music. -

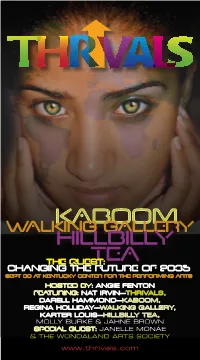

Kaboom Walking Gallery Hillbilly

founder's message KABOOM WALKING GALLERY HILLBILLY THE QUEST:TEA Changing the future of 2035 Sept 30 AT KENTUCKY CENTER FOR THE PerFORMING ARTS HOSTED BY: ANGIE FENTON FEATURING: NAT IRVIN—THRIVALS, DARELL HAMMOND—KABOOM, REGINA HOLLIDAY—WALKING GALLERY, KARTER LOUIS—HILLBILLY TEA, MOLLY BURKE & JAHNE BROWN SPECIAL GUEST: JANELLE MONÁE & THE WONDALAND ARTS SOCIETY www.thrivals.com founder's message Angie Fenton 8:30 WELCOME & OPENING REMARKS Nat Irvin, II, Founder of Thrivals, Woodrow M. Strickler Executive-in-Residence/Professor of Management Practice, College of Business, University of Louisville What if you lived in a city, town, village or slum that didn’t appear on a map? Officially the place you called home didn’t even exist. This was a reality for 14-year-old Salim Shekh and Sikha Patra, who grew up in one of the unchar- tered slums of Kolkata, India, or at least until they decided to do something about it. message Our theme for this year’s Thrivals was inspired by the idea of “positive disruption” as so powerfully from the dean demonstrated by these two young Indian teenagers. Their incredible quest has been documented in the film, The Revolutionary Optimists. Salim and Sikha are positively disrupting the deeply held cultural beliefs that members of their community hold about the future. Instead of the future being consigned to fate and destiny and even luck, Salim and Sikha say that the community’s future will depend on what the members of the community choose to do for themselves. Their message: Forget about fate and luck, and instead do something. -

Allegories of Afrofuturism in Jeff Mills and Janelle Monaé

Vessels of Transfer: Allegories of Afrofuturism in Jeff Mills and Janelle Monáe Feature Article tobias c. van Veen McGill University Abstract The performances, music, and subjectivities of Detroit techno producer Jeff Mills—radio turntablist The Wizard, space-and-time traveller The Messenger, founding member of Detroit techno outfit Underground Resistance and head of Axis Records—and Janelle Monáe—android #57821, Cindi Mayweather, denizen and “cyber slavegirl” of Metropolis—are infused with the black Atlantic imaginary of Afrofuturism. We might understand Mills and Monáe as disseminating, in the words of Paul Gilroy, an Afrofuturist “cultural broadcast” that feeds “a new metaphysics of blackness” enacted “within the underground, alternative, public spaces constituted around an expressive culture . dominated by music” (Gilroy 1993: 83). Yet what precisely is meant by “blackness”—the black Atlantic of Gilroy’s Afrodiasporic cultural network—in a context that is Afrofuturist? At stake is the role of allegory and its infrastructure: does Afrofuturism, and its incarnates, “represent” blackness? Or does it tend toward an unhinging of allegory, in which the coordinates of blackness, but also those of linear temporality and terrestial subjectivity, are transformed through becoming? Keywords: Afrofuturism, Afrodiaspora, becoming, identity, representation, race, android, alien, Detroit techno, Janelle Monáe tobias c. van Veen is a writer, sound-artist, technology arts curator and turntablist. Since 1993 he has organised interventions, publications, gatherings, exhibitions and broadcasts around technoculture, working with MUTEK, STEIM, Eyebeam, the New Forms Festival, CiTR, Kunstradio and as Concept Engineer and founder of the UpgradeMTL at the Society for Arts and Technology (SAT). His writing has appeared in many publications. -

Of Producing Popular Music

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 6-26-2019 1:00 PM The Elements of Production: Myth, Gender, and the "Fundamental Task" of Producing Popular Music Lydia Wilton The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Coates, Norma. The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Music © Lydia Wilton 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Wilton, Lydia, "The Elements of Production: Myth, Gender, and the "Fundamental Task" of Producing Popular Music" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6350. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6350 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Using Antoine Hennion’s “anti-musicology”, this research project proposes a methodology for studying music production that empowers production choices as the primary analytical tool. It employs this methodology to analyze Kesha’s Rainbow, Janelle Monáe’s Dirty Computer, and St. Vincent’s Masseduction according to four, encompassing groups of production elements: musical elements, lyrical elements, personal elements, and narrative elements. All three albums were critical and commercial successes, and analyzing their respective choices offers valuable insight into the practice of successful producers that could not necessarily be captured by methodologies traditionally used for studying production, such as the interview. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of -

Diversity of K-Pop: a Focus on Race, Language, and Musical Genre

DIVERSITY OF K-POP: A FOCUS ON RACE, LANGUAGE, AND MUSICAL GENRE Wonseok Lee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton Kristen Rudisill © 2018 Wonseok Lee All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Since the end of the 1990s, Korean popular culture, known as Hallyu, has spread to the world. As the most significant part of Hallyu, Korean popular music, K-pop, captivates global audiences. From a typical K-pop artist, Psy, to a recent sensation of global popular music, BTS, K-pop enthusiasts all around the world prove that K-pop is an ongoing global cultural flow. Despite the fact that the term K-pop explicitly indicates a certain ethnicity and language, as K- pop expanded and became influential to the world, it developed distinct features that did not exist in it before. This thesis examines these distinct features of K-pop focusing on race, language, and musical genre: it reveals how K-pop groups today consist of non-Korean musicians, what makes K-pop groups consisting of all Korean musicians sing in non-Korean languages, what kind of diverse musical genres exists in the K-pop field with two case studies, and what these features mean in terms of the discourse of K-pop today. By looking at the diversity of K-pop, I emphasize that K-pop is not merely a dance- oriented musical genre sung by Koreans in the Korean language. -

My Spaceship Leaves at 10: Blackness in the Global Future

My Spaceship Leaves At 10: Blackness in the Global Future Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of African and Afro-American Studies Faith Smith, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Natasha Iris Gayle Gordon May 2015 Committee Members: Professor Faith Smith Signature: ____________________ Professor Jasmine Johnson Signature: ____________________ Professor Greg Childs Signature: ____________________ 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people for their part in the making of this project: My mother, Annette Harris-Gordon: for sense of self, exploration of the quotidian fantastic, and frequent reminders throughout the production of this project to outline every thought. My advisor, Professor Faith Smith, for her help working through all aspects of the paper, willingness to discuss every detail, and general positive energy this past year. This thesis would not have been what it is today without her guidance. The African and Afro-American Studies Department and associated professors for their feedback, book recommendations, and useful web links: Professor Chad Williams, Professor Jasmine Elizabeth Johnson, Professor Wellington Nyangoni, Professor Derron Wallace, and Professor Gregory Childs. And Mohamed Abdirahman, Easter Peterson, Riley Sandberg, Britnie Smith, Brian Jones, and Keith Jones for endless encouragement. 3 What difference is there between Utopia and a dream? Just one. —Jean Pierre Bekolo We know that we are larger than life. We know that we are larger than Earth. We know we are larger than the cosmos. And that is reflected in our work and in our music. -

Billboard Magazine

11.02.2013 billboard.com billboard.biz ATLANTIC'S SUPER BOWL PLAY Doritos Partnership Drives Synchs NEW LIFE FOR RHAPSODY Telecom Bundles Drive 13* Scale FILM/TV MUSIC CONFERENCE HELLO, SIA 4. IL r!1 ti 14,1 410 $6 99US $8.99CAM 4 2> 7 896 47205 9 UK £5.50 "ONE OF THE BESTWorldMags.net"THE ARRIVAL OF "ONE OF THE MOST STRIKING STORIES IN POP" A NEW KIND OF STAR " ARTISTS IN R&B " -- ROLLING STONE -- ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY -- NEW YORK TIMES * * * * * * * * * * taylor swift lorde the weeknd *IDE / BILLBOARD TOP 200 ALBUMS a1 DEBUT / BILLBOARD TOP ROCK ALBUMS / BILLBOARD TOP R&B ALBUMS siSINt "I KNEW YOU WERE TROUBLE" #1 SINGLE "ROYALS"' "LIVE FOR" Source: Billboard Hot Digital Songs Source: Billboard Hot too Songs Source: rTunes / Top R&B / Soul Song's (8.20.13) "THIS MIGHT BE THE MOST -AN AMALGAM OF EVERYTHING "THE BIGGEST STORY IN COUNTRY INVITING POP RECORD OF 20f3 " YOU'D WANT FROM A NEW MUSIC THIS YEAR [201.91 IS MOST -- LA TIMES BLACK SABBATH ALBUM" -- NME CERTAINLY FLORIDA GEORGIA LINE" * * -- THE ARGUS LEADER * * * * * ariana grande black sabbath florida #1 DEBUT / BILLBOARD TOP 200 ALBUMS / BILLBOARD TOP 200 ALBUMS #1 SINGLE "THE WAY"" "GOD IS DEAD" georgia line #1 DEBUT / BILLBOARD TOP COUNTRY ALBUMS #1 SINGLE "CRUISE"` -.+111P. Source: iTures / Top Singles (3.25.r3) Source: Mechabase Mainstream Rock (5.24,3) "...HELLA-COOL DEBUT" `AN ARTISTIC TOUR DE FORCE THAT ROWLAND STEPS OUT WITH PEOPLE FURTHERS THE POTENT/AL SHOWN SURE FOOTING, A GIRL -NEXT * * * * ON GROUP'SAWARD-WINNING DEBUT. " DOOR WHO BELONGS ON TOP" -- THE ASSOCIATED PRESS - SPIN of monsters * * * * * and men the band perry kelly rowland *1DEBI./ BILLBOARD TOP ROCK ALBUMS #1 DEBUT / BILLBOARD TOP COUNTRY ALBUMS / BILLBOARD TOP R&B ALBUMS "LITTLE TALKS" #1 SINGLE "BETTER DIG TWO"` "KISSES DOWN LOW" *t- IN V ' Atk 4446 A Irrirffei Source: Billboard Country Airplay republic for your grammy® consideration WorldMags.net WorldMags.net THIS WEEK Volume 125 [ No. -

Heavy on the Air: Radio & Promotion in the Heavy

HEAVY ON THE AIR: RADIO & PROMOTION IN THE HEAVY METAL CAPITAL OF THE WORLD by Ted Jacob Dromgoole, B.A. A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in History May 2021 Committee Members: Jason Mellard, Chair Shannon Duffy Thomas Alter COPYRIGHT by Ted Jacob Dromgoole 2021 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, Section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgment. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Ted Jacob Dromgoole, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. DEDICATION For Delleney and Emmylou. Thank you for being by my side through it all. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to bestow the greatest of thanks to my partner Delleney. Every idea or thought I had, I shared with her first. She is my rock, my inspiration and my home. Thank you for believing in me as deeply as you have. I am so incredibly fortunate to have you in my life. To my mother and her partner, Papa Steve, thank you for your wisdom and support during this whole process. Mom, thank you for inspiring in me a lifelong love of history, beginning with the What Your 5th Grader Should Know books.