Lucid Dreaming: New Perspectives on Consciousness in Sleep

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pilgrimage to India

Winter 2010 Gaden Khachoe Shing Tibetan Buddhist Monastery Page 1 Dagom Gaden Tensung Ling Tibetan Buddhist Monastery Gaden Samdrup Ling Tibetan Buddhist Monastery Winter 2010 Pilgrimage to India We went to India to celebrate the dedication of the new Shar Gaden temple and along the way had an opportunity to walk in the footsteps of thousands of Buddhists who went before us. This journey began on Oct. 23 with three monks and 16 lay students heading to Mumbai, India. Our first visit was to the Kanheri Caves in the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. These caves were carved out of cliffs as a place for monks to study and practice Buddhism. They date from 1st century BCE to 9th century CE. They were commissioned by royal families, merchants and others to support the monks in their efforts to practice countryside few foreigners get to see. Fields younger monks sitting near us were very the dharma. of sugar cane, rice and corn next to tree-lined busy watching us most of the time. In the center of some of the caves are roads took us through the town of Mundgod What followed were an official ribbon large stupas. Thousands of intricate carvings and to a warm welcome by the Shar Gaden cutting ceremony, a meeting of the Dorje of Buddhas, bodhisattvas and other Buddhist monks. Shugden Religious and Charitable Society images cover the walls. As in other cultures, After we arrived and enjoyed tea, we and an evening performance by the monks much of the ancient art in India is based settled into our rooms. -

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

Phenomenology of Embodied Dreamwork with Puerto Rican Women: a Dissertation Lourdes F

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Expressive Therapies Dissertations (GSASS) 2010 Phenomenology of Embodied Dreamwork with Puerto Rican Women: A Dissertation Lourdes F. Brache-Tabar Lesley University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_dissertations Part of the Art Therapy Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, and the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Brache-Tabar, Lourdes F., "Phenomenology of Embodied Dreamwork with Puerto Rican Women: A Dissertation" (2010). Expressive Therapies Dissertations. 46. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_dissertations/46 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Expressive Therapies Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Phenomenology of Embodied Dreamwork with Puerto Rican Women A DISSERTATION (submitted by) Lourdes F. Brache-Tabar In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy LESLEY UNIVERSITY May 2010 2 3 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This dissertation has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at Lesley University and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this dissertation are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his or her judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. -

THE RIMAY TRADITION by Lama Surya Das The

THE RIMAY TRADITION by Lama Surya Das The nonsectarian Rimay movement of Tibet is an ecumenical tradition started-- or more, accurately, revived--one hundred and forty years ago by the great Manjusri (wisdom) lamas of eastern Tibet renowned as the First Khyentse and First Kongtrul. It arose in order to preserve and help disseminate the many different lineages and practices of all the extant schools of Tibetan Buddhism, many of which were in danger of being lost. These extraordinarily learned and accomplished nonsectarian masters studied under hundreds of teachers and internalized the precious and profound Three Yana teachings, then taught and also compiled the bulk of them into voluminous compendiums, vast scriptural compilations such as the Rinchen Terdzod (Treasury of Visionary Revelations) and the Shayja Dzod (Treasury of Knowledge). Rimay means unbounded, all-embracing, unlimited, and also unbiased and impartial. The Karmapas, the Dalai Lamas, Sakya lineage heads, and major Nyingma and other lineage holders and founders (such as Je Tsongkhapa and Gyalwa Longchenpa) all took teachings and empowerments from various schools and lineages, and later practiced and authentically transmitted those traditions. The two enlightened nineteenth century renaissance-type masters, Khyentse and Kongtrul, were aided and abetted in this ambitious endeavor by the visionary Chogyur Lingpa as well as the younger and indomitable master Mipham, most of whom exchanged teachings and practices with each other in an unusually humble and collegial way. Other notable Tibetan Lamas widely renowned for their non-sectarian approach were Patrul Rinpoche and Lama Shabkar, Dudjom Lingpa and the Fifteenth Karmapa Khakyab Dorje. The present Fourteenth Dalai Lama of Tibet himself embodies and promotes this important tradition; he always mentions the importance of this inclusive, tolerant and open-minded Rimay spirit, wherever he goes, in his teachings and talks today. -

Daughter Album If You Leave M4a Download Download Verschillende Artiesten - British Invasion (2017) Album

daughter album if you leave m4a download Download Verschillende artiesten - British Invasion (2017) Album. 1. It's My Life 2. From the Underworld 3. Bring a Little Lovin' 4. Do Wah Diddy Diddy 5. The Walls Fell Down 6. Summer Nights 7. Tuesday Afternoon 8. A World Without Love 9. Downtown 10. This Strange Effect 11. Homburg 12. Eloise 13. Tin Soldier 14. Somebody Help Me 15. I Can't Control Myself 16. Turquoise 17. For Your Love 18. It's Five O'Clock 19. Mrs. Brown You've Got a Lovely Daughter 20. Rain On the Roof 21. Mama 22. Can I Get There By Candlelight 23. You Were On My Mind 24. Mellow Yellow 25. Wishin' and Hopin' 26. Albatross 27. Seasons In the Sun 28. My Mind's Eye 29. Do You Want To Know a Secret? 30. Pretty Flamingo 31. Come and Stay With Me 32. Reflections of My Life 33. Question 34. The Legend of Xanadu 35. Bend It 36. Fire Brigade 37. Callow La Vita 38. Goodbye My Love 39. I'm Alive 40. Keep On Running 41. The Hippy Hippy Shake 42. It's Not Unusual 43. Love Is All Around 44. Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood 45. The Days of Pearly Spencer 46. The Pied Piper 47. With a Girl Like You 48. Zabadak! 49. I Only Want To Be With You 50. Here It Comes Again 51. Don't Let the Sun Catch You Crying 52. Have I the Right 53. Darling Be Home Soon 54. Only One Woman 55. -

Rime Jewel Fall 2017

Rime Buddhist Center 700 West Pennway Kansas City, MO 64108 www.rimecenter.org 816-471-7073 Fall 2017 Increase your knowledge, Season Changes at the check out the class Rime Center schedule! Kum Nye – Tibetan Yoga Workshop with Santosh Philip Lama Rod Owens: September 22 - 24, 2017 Ven. Phakyab We are delighted to welcome Radical Dharma November 10 – 12, 2017 to Kansas City and the Rime Rinpoche: The Healing We are extremely delighted to Center Santosh Philip, September Power of the Mind welcome to Kansas City and the 22nd through 24th. Santosh will October 13 – 15, 2017 Rime Center Lama Rod Owen, be leading us in a system of Mark your calendars as we November 10th & 12th. Lama Rod Tibetan yoga called Kum Nye. welcome the return to Kansas will be teaching from his book Based on a traditional healing City and the Rime Center the Radical Dharma. Igniting a long- system, Kum Nye Yoga helps acclaimed Tibetan Buddhist overdue dialogue about how the to relieve stress, transform lama and healer, Ven. Phakyab legacy of racial injustice and white negative patterns and promote Rinpoche, October 13th & 15th. supremacy plays out in society at balance and health. Developed Ven. Phakyab Rinpoche will be large and Buddhist communities by Tibetan Lama Tarthang Tulku, teaching from his book Meditation in particular, this urgent call to this presentation of Kum Nye Saved My Life: A Tibetan Lama action outlines a new dharma practices is thoroughly modern and the Healing Power of the that takes into account the and adapted specifically to suit Mind. ways that racism and privilege modern needs. -

Tibetan Yoga: a Complete Guide to Health and Wellbeing Pdf, Epub, Ebook

KUM MYE : TIBETAN YOGA: A COMPLETE GUIDE TO HEALTH AND WELLBEING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tarthang Tulku | 424 pages | 30 Apr 2007 | Dharma Publishing,U.S. | 9780898004212 | English | Berkeley, United States Kum Mye : Tibetan Yoga: a Complete Guide to Health and Wellbeing PDF Book Product Details About the Author. We develop our own language to explore feeling, dropping the labels and stories we might have attached to our vast array of feeling, and watching as they expand and flow. History Timeline Outline Culture Index of articles. Having established a foundation of calmness, we are ready to experience the unique tonal quality of all of the sensations in the body, and begin to explore the relationship between 'inner' and 'outer. The foundation of Kum Nye is deep relaxation, first at the physical level of tension, and then at the level of tension between us and the world around us, and finally, at the level of tension between our individual purpose and the flow of life. Sign in to Purchase Instantly. Practices and attainment. Thoughts on transmission : knowingness transforms causal conditions 2 copies. Tanya Roberts' publicist says she is not dead. Its benefits are said to include elimination of toxins, increased vitality, pain reduction, and calming of nervous disorders including insomnia, depression and anxiety. Skillful Means copies. People might be disappointed by the paucity of exertion during a Kum Nye practice, but then surprised by the depth of relaxation after a session. No events listed. In he moved to the United States where he has lived and worked ever since. Like this: Like Loading Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. -

Matchbox Dreams

Matchbox Dreams Book 1: The Drapkin kids in Dreamland DOUGLAS SCHWARTZ Copyright © 2019 by Douglas Schwartz All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. ii FOREWORD (For parents to read before reading the first story) About Dreams What Do Toddlers Dream About? By Dr. Harvey Karp From infants to adults, everyone dreams. Psychologist David Foulkes studies children (from tots to teens) to bring the secrets of their dreams to the light of day. In his lab, he lets kids fall asleep and then wakes them three times a night—sometimes in REM and sometimes in NREM—and asks them to describe what they recall. Foulkes’ findings are surprising…in how unsurprising they are. Basically, little kids have little dreams. But exactly what kids see while dreaming depends on their age. As children develop and grow, their dreams do too. Toddler dreams are usually just snapshots, looking much more like a slide show than a movie when compared to the dreams of adults. They heavily feature animals and other familiar sights, like images of people eating. According to Foulkes, “Children’s dream life…seems to be similar to their waking imagination and narration,” he explains in his study, Children’s Dreaming and the Development of Consciousness. “Animals carry human concerns and readily become objects of identification.” iii Understandably, dreams can confuse small kids. -

Tarthang Tulku Gesture of Balance

Gesture of Balance A Guide to Awareness, Self-Healing, and Meditation Tarthang Tulku Contents Foreword v Preface ix PART ONE: OPENING Impermanence and Frustration 3 Beginning with Honesty 16 Taking Responsibility 25 Opening the Heart 31 Awakening Compassion 37 PART TWO: RELAXATION Expanding Feeling 47 Body, Breath, and Mind 54 Healing through Positive Energy 60 PART THREE: MEDITATION Unfolding Meditation 69 Observing Thoughts 74 Transforming Anxiety 78 Attaining Inner Confidence 84 Discovering Mind 91 The Natural State of Mind 96 Becoming the Meditation Experience 102 PART FOUR: AWARENESS Visualization and Seeing 123 Meditative Awareness 135 Developing Balance 143 PART FIVE: TRANSMISSION The Teacher-Student Relationship 155 Trusting the Inner Teacher 163 Foreword he essays in this book are unusual in the sense that they present Buddhist ideas and perspectives without indulging in theories about Buddhism. The very fact that we in the Western world speak about Buddhism as if it were a rigid system, that can (and maybe should) be dealt with in abstract terms, shows how little real understanding of a different set of values exists even at the present time. These values are inherent in a person's life and are not merely arbitrarily assigned to it. The following essays address themselves to the living person, not to an abstraction or a shadowy image; and they do so in terms which a living person can understand intellectually as well as feel deep within his heart. That is why these essays are unusual- they are not simply props or pegs on which to hang one's preconceptions, but stimulants to reconsider and to reassess the situation in which we find ourselves; and through this re-awakening to what is at hand, we are stimulated to set out on the path toward growth and maturation. -

Applications of Lucid Dreaming in Sports Paul Tholey J. W. Goethe

Lucidity Letter December, 1990, Vol. 9, No. 2 Applications of Lucid Dreaming in Sports Paul Tholey J. W. Goethe-Universitat The following article has above all a practical orientation. The various possibilities for the application of lucid dreaming in sports training are presented and briefly illustrated. These theses are based on findings from experiments with experienced lucid dreamersi who were instructed to carry out various routine and sport-related actions while lucid-dreaming, with the object of observing the effects on both dreaming and waking states (Tholey, 1981a). Additionally, I report here on numerous spontaneous accounts of athletes who have mastered lucid dreaming, as well as my own years of experience as a lucid dreamer and as an active competitor in different types of sports. With regard to theoretical principles I have relied on the gestalt theory of sports as it was first systematically presented by Kohl after numerous phenomenological and objective experiments (Kohl, 1956), and as it was further developed in my own work (Tholey, 1981b). The latter explored the significance of lucid dreaming to sports. Due to space limitations, only the most important theoretical conceptions concerning the application of lucid dreaming to sports training will be discussed here. Basic Theoretical Principles According to gestalt theory, the complex sensory-motor feedback system of the human physical organism is to be conceived of as a servo-mechanism which serves the finely- tuned, energy-saving control of the organism. The main control center of this circuit system lies in the brain. There the physical world is represented more or less exactly as the phenomenal world (phenomenal body ego and phenomenal environment) by means of sensory processes. -

Press Contact Information

What does it take to keep a culture’s sacred knowledge from being lost to history? THE GREAT TRANSMISSION A feature-length documentary film Running time: 56 minutes Year: 2015 Languages: English, Tibetan (subtitled) Countries of Production: US, Tibet, India Producer: Guna Foundation Press Contact information: Hyeryun Park Guna Foundation 2018 Allston Way Berkeley, CA 94704 [email protected] 510-809-1553 www.thegreattransmission.com Short Synopsis Imagine that you are one of a handful of survivors of a disaster that has virtually erased your culture. Now you must recover the knowledge that was lost and find ways to ensure that it continues into the future. Witnessing the disintegration of his heritage, Tibetan refugee and Buddhist lama Tarthang Tulku dedicated his life to restoring a text tradition that was nearly lost during the turbulence of the 20th century. Working with a handful of volunteers, he would eventually deliver over four and a quarter million books into Tibetan hands, in one of the largest free book distributions in history. The Great Transmission is the story of one Tibetan refugee lama and his efforts to preserve the sacred texts of his tradition. But more than that, it is the story of the epic journey of a precious inheritance of human knowledge from its origins in Ancient India to the present day, and the celebration of the valiant efforts of those devoted to its survival. Long Synopsis Imagine that you are one of a handful of survivors of an event that has virtually erased your culture. Now you must start from scratch—locating the lost knowledge and finding ways to ensure that it continues into the future. -

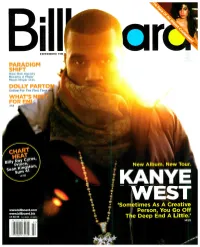

`Sometimes As a Creative

EXPERIENCE THE PARADIGM SHIFT How One Agency Became A Major Music Player >P.25 DOLLY PARTO Online For The First Tim WHAT'S FOR >P.8 New Album. New Tour. KANYE WEST `Sometimes As A Creative www.billboard.com Person, You Go Off www.billboard.biz US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK E5.50 The Deep End A Little.' >P.22 THE YEAR MARK ROHBON VERSION THE CRITICS AIE IAVIN! "HAVING PRODUCED AMY WINEHOUSE AND LILY ALLEN, MARK RONSON IS ON A REAL ROLL IN 2007. FEATURING GUEST VOCALISTS LIKE ALLEN, IN NOUS AND ROBBIE WILLIAMS, THE WHOLE THING PLAYS LIKE THE ULTIMATE HIPSTER PARTY MIXTAPE. BEST OF ALL? `STOP ME,' THE MOST SOULFUL RAVE SINCE GNARLS BARKLEY'S `CRAZY." PEOPLE MAGAZINE "RONSON JOYOUSLY TWISTS POPULAR TUNES BY EVERYONE FROM RA TO COLDPLAY TO BRITNEY SPEARS, AND - WHAT DO YOU KNOW! - IT TURNS OUT TO BE THE MONSTER JAM OF THE SEASON! REGARDLESS OF WHO'S OH THE MIC, VERSION SUCCEEDS. GRADE A" ENT 431,11:1;14I WEEKLY "THE EMERGING RONSON SOUND IS MOTOWN MEETS HIP -HOP MEETS RETRO BRIT -POP. IN BRITAIN, `STOP ME,' THE COVER OF THE SMITHS' `STOP ME IF YOU THINK YOU'VE HEARD THIS ONE BEFORE,' IS # 1 AND THE ALBUM SOARED TO #2! COULD THIS ROCK STAR DJ ACTUALLY BECOME A ROCK STAR ?" NEW YORK TIMES "RONSON UNITES TWO ANTITHETICAL WORLDS - RECENT AND CLASSIC BRITPOP WITH VINTAGE AMERICAN R &B. LILY ALLEN, AMY WINEHOUSE, ROBBIE WILLIAMS COVER KAISER CHIEFS, COLDPLAY, AND THE SMITHS OVER BLARING HORNS, AND ORGANIC BEATS. SHARP ARRANGING SKILLS AND SUITABLY ANGULAR PERFORMANCES! * * * *" SPIN THE SOUNDTRACK TO YOUR SUMMER! THE .