4 Ecological Environmental Effects Assessment Methods for Deterministic Oil Spill Modelling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Program and Abstracts

PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 47TH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL ARCTIC WORKSHOP March 23-25, 2017 Buffalo, New York Sponsored and Hosted by: University at Buffalo Center for GeoHazards Studies College of Arts and Sciences Department of Geology The RENEW Institute Organizing Committee: Jason Briner Barbara Catalano Beata Csatho Avriel Schweinsberg Elizabeth Thomas Greg Valentine 1 2 Introduction Overview and history The 47th Annual International Arctic Workshop will be held March 23-25, 2017, on the campus of the University of Buffalo. The meeting is sponsored and hosted by the University at Buffalo, Center for GeoHazard Studies, College of Arts and Sciences, Department of Geology, and the RENEW Institute. This workshop has grown out of a series of informal annual meetings started by John T. Andrews and sponsored by INSTAAR and other academic institutions worldwide. 2017 Theme “Polar Climate and Sea Level: Past, Present & Future” Website https://geohazards.buffalo.edu/aw2017 Check-In / Registration Please check in or register on (1) Wednesday evening at the Icebreaker/Reception between 5:00 – 7:00 pm in the Davis Hall Atrium (UB North Campus), or (2) Thursday morning between 8:00 – 8:45 am in the Davis Hall Atrium. At registration those who have ordered a print version will also receive their printed high-resolution volume. Davis Hall Davis Hall is located between Putnam Way and White Road on the UB North Campus. Davis Hall is directly north of Jarvis Hall and east of Ketter Hall. To view an interactive map of North Campus, please visit this webpage: https://www.buffalo.edu/home/visiting- ub/CampusMaps/maps.html Wi-Fi Wireless internet access is available (“UB_Connect”). -

The Early Wisconsinan History of the Laurentide Ice Sheet

Document generated on 10/05/2021 2:08 a.m. Géographie physique et Quaternaire The Early Wisconsinan History of the Laurentide Ice Sheet L’évolution de la calotte glaciaire laurentidienne au Wisconsinien inférieur Geschichte der laurentischen Eisdecke im frühen glazialen Wisconsin Jean-Serge Vincent and Victor K. Prest La calotte glaciaire laurentidienne Article abstract The Laurentide Ice Sheet The identification, particularly at the periphery of the ice sheet, of glacigenic Volume 41, Number 2, 1987 sediments thought to postdate nonglacial sediments or paleosols regarded as having been laid down sometime during the Sangamonian Interglaciation URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/032679ar (stage 5) and thought to predate nonglacial sediments or soils reckoned to be of DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/032679ar Middle Wisconsinan age (stage 3), has led numerous authors to propose that the Laurentide Ice Sheet initially grew during the Sangamonian and/or the Early Wisconsinan (stage 4). The evidence for the beginning of the See table of contents Wisconsinan ice sheet in various areas of Canada and the northern United States is briefly reviewed. The general absence of sound geochronometric frameworks for potential Sangamonian or Early Wisconsinan glacial deposits Publisher(s) has led to a situation where in most areas it can be argued, depending on one's interpretation, that ice completely inundated or was completely absent at that Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal time. On the premise (perhaps false) that Laurentide Ice was in fact extensive during the Early Wisconsinan, a map showing maximum possible ice extent, as ISSN put forward by some authors is presented and the glacigenic units possibly 0705-7199 (print) recording the ice advance are shown in a correlation chart. -

Baffin Island: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961-1967

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2016-02 Baffin Island: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961-1967 Ives, Jack D. University of Calgary Press Ives, J.D. "Baffin Island: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961-1967." Canadian history and environment series; no. 18. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2016. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51093 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca BAFFIN ISLAND: Field Research and High Arctic Adventure, 1961–1967 by Jack D. Ives ISBN 978-1-55238-830-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 – SEAL WATERSHED .............................................................................................................................................. 4 2 - THLEWIAZA WATERSHED ................................................................................................................................. 5 3 - GEILLINI WATERSHED ....................................................................................................................................... 7 4 - THA-ANNE WATERSHED .................................................................................................................................... 8 5 - THELON WATERSHED ........................................................................................................................................ 9 6 - DUBAWNT WATERSHED .................................................................................................................................. 11 7 - KAZAN WATERSHED ........................................................................................................................................ 13 8 - BAKER LAKE WATERSHED ............................................................................................................................. 15 9 - QUOICH WATERSHED ....................................................................................................................................... 17 10 - CHESTERFIELD INLET WATERSHED .......................................................................................................... -

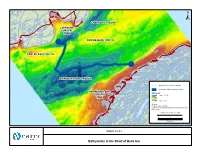

Bathymetry in the Strait of Belle Isle

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! L'Anse Amour ! -80 -60 ! Forteau -50 ! ± LABRADOR TROUGH LABRADOR COASTAL -100 ZONE -80 -80 -1 00 L'Anse-au-Clair ! CENTRE BANK NORTH -90 ! -50 CENTRE BANK SOUTH -40 -60 0 -100 Green Island Cove 5 -60 ! - -80 -90 ! Pines Cove ! -100 Shoal Cove ! Sandy Cove ! NEWFOUNDLAND TROUGH -10 -20 Savage Cove ! -9 0 -30 Bathymetry Lines (10 m interval) 00 -1 Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor - ! 1 0 0 0 NEWFOUNDLAND -1 0 Bathymetry * COASTAL High : 127.09 -2 Flower's Cove ZONE0 ! -70 Low : -0.16 Sources: * Fugro Jacques (2007) Location of troughs and banks from Woodworth-Lynas et al. (1992). -60 FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_406a ! 0 3 6 0 Kilometres -5 -80 ! ! FIGURE 10.5.2-2 ! Bathymetry in the Strait of Belle Isle ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! -

Arctic Geopolitics & Autonomy

ISBN 978-3-7757-2681-8 Arctic Perspective Cahier No. 2 2 No. Cahier Perspective Arctic Arctic Perspective Cahier No. 2 9 783775 726818 Edited by Michael Bravo 116 pages 53 illustrations & Nicola Triscott 24 in color ARCTIC GEOPOLITICS & AUTONOMY & GEOPOLITICS ARCTIC “This is a story about the stories we Arctic tell of human movement out of Africa and around the world. It’s Geopolitics & stories at three levels, or maybe it’s stories all the way down.” Autonomy Bravo & Triscott & Bravo eastern Arctic territory of Nunavut.” Nunavut.” of territory Arctic eastern most of those I know in Canada’s north- Canada’s in know I those of most also seems to apply to Inuit men, at least least at men, Inuit to apply to seems also pleasure of using technological devices devices technological using of pleasure country and culture, love gadgets? The The gadgets? love culture, and country “Is it a truism that men, regardless of of regardless men, that truism a it “Is Arctic Geopolitics & Autonomy Plate 1 Simon Quassa from the Inuit Broadcasting Corporation relaxing with a ringed seal in the foreground after a day of filming seals for a documentary, 1988. Photo: Michael Bravo 3 Arctic Perspective Cahier No. 2 Arctic Geopolitics & Autonomy Plate 2 Pudlo Pudlat, Aeroplane, 1976. Reproduced with the permission of Dorset Fine Arts 4 5 Arctic Perspective Cahier No. 2 Arctic Geopolitics & Autonomy Plate 3 Nathalie Grenzhaeuser, Hotellneset, 2007, from the series The Construction of the Quiet Earth. LightJet print, Diasec matte, 120 x 160 cm, edition 5 & 2 AP Plate 5 Hunters survey the sea ice off the coast of Igloolik, 1988. -

Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research

Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research 2001–2002 Biennial Report Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research University of Colorado 450 UCB Boulder, Colorado 80309-0450 Tel 303/492-6287 Fax 303/492-6388 www.instaar.colorado.edu RL-1 1560 30th Street Boulder, CO 80303 Mountain Research Station 818 County Road 116 Nederland, Colorado 80466 Tel 303/492-8842 Fax 303/492-8841 (Director: William B. Bowman) www.colorado.edu/mrs/ INSTAAR Council Carol B. Lynch, Vice Chancellor for Research and Dean of the Graduate School Todd Gleason, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Robert Davis, Dean, College of Engineering Charles Stern, Chair/Professor, Department of Geological Sciences Kenneth Foote, Chair/Professor, Department of Geography Russell Monson, Chair/Professor, Environmental, Population and Organismic Biology Hon-Yim Ko, Chair/Professor, Department of Civil, Environmental, and Architectural Engineering James P. Syvitski, Director/Professor, INSTAAR/Department of Geological Sciences INSTAAR Scientific Advisory Committee Richard Alley, Professor, Department of Geosciences, Pennsylvania State University William Fitzhugh, Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution Hugh French, Professor, Departments of Geography and Earth Sciences, University of Ottawa Peter Groffman, Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Millbrook, NY Steve Hargreaves, CEO, ERIC Companies, Englewood, CO Robert Howarth, Program in Biogeochemistry and Environmental Change, Cornell University Tim Killeen, Director, National Center for Atmospheric -

Ice in the Eastern Canadian Arctic$ Gifford H

Quaternary Science Reviews 21 (2002) 33–48 The Goldilocks dilemma: big ice, little ice, or ‘‘just-right’’ ice in the Eastern Canadian Arctic$ Gifford H. Millera,b,*, Alexander P. Wolfea,c, Eric J. Steiga,d, Peter E. Sauera,b,e, Michael R. Kaplana,b,f, Jason P. Brinera,b a Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0450, USA b Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0399, USA c Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB T6G 2G9, Canada d Quaternary Research Center and Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA e Biogeochemistry Labs, Indiana University, 1001E 10th St, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA f Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA Received 15 March 2001; accepted 30 August 2001 Abstract Our conceptions of the NE sector of the Laurentide Ice Sheet (LIS) at the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) have evolved through three major paradigms over the past 50 years. Until the late 1960s the conventional view was that the Eastern Canadian Arctic preserved only a simple deglacial sequence from a LIS margin everywhere at the continental shelf edge (Flint Paradigm). Glacial geologic field studies began in earnest in this region in the early 1960s, and within the first decade field evidence documenting undisturbed deposits predating the LGM led a pendulumswing to a consensus view that large coastal stretches of the Eastern Canadian Arctic remained free of actively eroding glacial ice at the LGM, and that the most extensive ice margins occurred early in the last glacial cycle. -

Energy F De .Lj ~1:I500b - Co~ __- Gjl /O~ -'::>1 :)Ffshore

TRIM Jl ~.~ J c:''723;;l.. Dt,te n':"'_,f\yr; I~~c~I_,_ 0-..-'-' -c: Energy f de .lj ~1:i500b -_cO~ __-_gJl /O~ -'::>1 :)ffshore _,. .Jvurd ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR MARINE 2D SEISMIC REFLECTION SURVEY LABRADOR SEA AND DAVIS STRAIT OFFSHORE LABRADOR BY MULTI KLiENT INVEST AS (MKI) Report No. HOP0417 RPS Energy (Halifax) Liberty Place, 2nd Floor Authors Tony LaPierre, M.A.Sc., P.Geoph. 1545 Birmingham Street Alexandra Arnott, PhD. (Earth Sciences) Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3J 2J6 Chris Hawkins, PhD. (Marine Ecology) Canada Kent Simpson, B.Sc., Dip. GIS, P. Geo. Tel: +1 9024251622 Darlene Davis, Project Co-ordinator Fax: +1 902 425 0703 Web: www.rpsgroup.com/energy/ Date of Issue March zs", 2011 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 10 1.1 2D MARINE SEISMIC EXPLORATION SURVEY ..................................... 12 2. REGULATORY REQUIREMENTS AND JURISDICTION ................................ 14 3. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ............................................................................... 15 3.1 PURPOSE ................................................................................................. 15 3.2 LOCATION ................................................................................................ 15 3.3 SITE HISTORY .......................................................................................... 15 3.4 SCHEDULE ............................................................................................... 15 3.4.1 Operating Schedule -

Fiord to Deep Sea Sediment Transfers Along the Northeastern Canadian Continental Margin

Document generated on 09/30/2021 11:09 a.m. Géographie physique et Quaternaire Fiord to Deep Sea Sediment Transfers along the Northeastern Canadian Continental Margin: Models and Data Transfert de sédiments des fjords à la haute mer, le long de la marge continentale du nord-est du Canada: modèle et données Sedimentbeförderungen vom Fjord zur Tiefsee entlang des nordöstlichen kanadischen Kontinentalsaums: Modelle und Daten John T. Andrews Volume 44, Number 1, 1990 Article abstract In Alaskan fiords, sedimentation rates are high; during a glacial advance URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/032798ar fiord-basin sediments are transported to the ice front to form a shoal which DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/032798ar reduces the calving rate. Thus, during successive glacial cycles, sediment is initially stored and then removed from fiord basins. In the fiords of eastern See table of contents Baffin Island sedimentation rates are, and were, much lower (< 1000 Kg/m2 ka). and fiord-basin fills may span several glacial cycles. This hypothesis is in keeping with the relatively low sedimentation rates on the adjacent shelf (50 to Publisher(s) 500 kg/m2 ka) and deep-sea plain (< = 50 kg/m2 ka). The advance of outlet glaciers through these arctic fiords may be explained by the in situ growth of a Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal floating ice-shelf, grounded at the mouth of the fiord. The extent of late Foxe Glaciation in McBeth and ltirbilung fiords can be delimited by raised marine ISSN deltas (50-85 m asl) with 14C dates on in situ shells and whalebone of >54 ka. -

EBSA) in the Eastern Arctic Biogeographic Region

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Research Document 2017/080 Central and Arctic Region Information in support of the evaluation of Ecologically and Biologically Significant Areas (EBSA) in the Eastern Arctic Biogeographic Region O. Schimnowski, J.E. Paulic, and K.A. Martin Fisheries and Oceans Canada Freshwater Institute 501 University Crescent Winnipeg, MB R3T 2N6 January 2018 Foreword This series documents the scientific basis for the evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of the day in the time frames required and the documents it contains are not intended as definitive statements on the subjects addressed but rather as progress reports on ongoing investigations. Research documents are produced in the official language in which they are provided to the Secretariat. Published by: Fisheries and Oceans Canada Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat 200 Kent Street Ottawa ON K1A 0E6 http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas-sccs/ [email protected] © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2018 ISSN 1919-5044 Correct citation for this publication: Schimnowski, O., Paulic, J.E., and Martin, K.A. 2018. Information in support of the evaluation of Ecologically and Biologically Significant Areas (EBSA) in the Eastern Arctic Biogeographic Region. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2017/080. v + 109 p. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................... IV RÉSUMÉ .................................................................................................................................. -

Holocene Glaciation and Climate Evolution of Baffin Island, Arctic Canada

Quaternary Science Reviews 24 (2005) 1703–1721 Holocene glaciation and climate evolution ofBaffinIsland, Arctic Canada Gifford H. Millera,Ã, Alexander P. Wolfeb, Jason P. Brinera,e, Peter E. Sauerc, Atle Nesjed aINSTAAR and Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado, 1560 30th St. Campus Box 450, Boulder, CO 80303, USA bDepartment of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, T6G 2E3 Canada cDepartment of Geological Sciences, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405-1405, USA dDepartment of Earth Science, University of Bergen, Alle´gaten 41, 5007 Bergen, Norway eDepartment of Geology, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY 14260 USA Received 28 January 2004; accepted 9 June 2004 Abstract Lake sediment cores and cosmogenic exposure (CE) dates constrain the pattern ofdeglaciation and evolution ofclimate across Baffin Island since the last glacial maximum (LGM). CE dating of erratics demonstrates that the northeastern coastal lowlands became ice-free ca.14 ka as the Laurentide Ice Sheet (LIS) receded from its LGM margin on the continental shelf. Coastal lakes in southeastern Baffin Island started to accumulate sediment at this time, whereas initial lacustrine sedimentation was delayed by two millennia in the north. Reduced organic matter in lake sediment deposited during the Younger Dryas chron, and the lack ofa glacial readvance at that time suggest cold summers and reduced snowfall. Ice retreated rapidly after 11 ka but was interrupted by a widespread readvance ofboth the LIS and local mountain glaciers 9.6 ka (Cockburn Substage). A second readvance occurred just before 8 ka during a period of unusually cold summers, corresponding to the 8.2 ka cold event in the Greenland Ice Sheet.