The Cut and the Continuum: Sophie Ristelhueber's Anatomical Atlas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Who 4 Ep.18.GOLD.SCW

DOCTOR WHO 4.18 by Russell T Davies Shooting Script GOLDENROD ??th April 2009 Prep: 23rd February Shoot: 30th March Tale Writer's The Doctor Who 4 Episode 18 SHOOTING SCRIPT 20/03/09 page 1. 1 OMITTED 1 2 FX SHOT. GALLIFREY - DAY 2 FX: LONG FX SHOT, craning up to reveal the mountains of Gallifrey, as Ep.3.12 sc.40. But now transformed; the mountains are burning, a landscape of flame. The valley's a pit of fire, cradling the hulks of broken spaceships. Keep craning up to see, beyond; the Citadel of the Time Lords. The glass dome now cracked and open. CUT TO: 3 INT. CITADEL - DAY 3 FX: DMP WIDE SHOT, an ancient hallway, once beautiful, high vaults of stone & metal. But the roof is now broken, open to the dark orange sky, the edges burning. Bottom of frame, a walkway, along which walk THE NARRATOR, with staff, and 2 TIME LORDS, the latter pair in ceremonial collars. FX: NEW ANGLE, LONG SHOT, the WALKWAY curves round, Narrator & Time Lords now following the curve, heading towards TWO HUGE, CARVED DOORS, already open. A Black Void beyond. Tale CUT TO: 4 INT. BLACK VOID 4 FX: OTHER SIDE OF THE HUGE DOORS, NARRATOR & 2 TIME LORDS striding through. The Time Lords stay by the doors, on guard; lose them, and the doors, as the Narrator walks on. FX: WIDE SHOT of the Black Void - like Superman's Krypton, the courtroom/Phantom Zone scenes - deep black, starkly lit from above. Centre of the Void: a long table, with 5 TIME LORDS in robes Writer's(no collars) seated. -

PROFIBUS Master Unit

MachineZX-T Automation Series Controller CJ-series PROFIBUS Master Unit Operation Manual for NJ-series CPU Unit CJ1W-PRM21 PROFIBUS Master Unit W509-E2-01 Introduction Introduction Thank you for purchasing a CJ-series CJ1W-PRM21 PROFIBUS Master Unit. This manual contains information that is necessary to use the CJ-series CJ1W-PRM21 PROFIBUS Master Unit for an NJ-series CPU Unit. Please read this manual and make sure you understand the functionality and performance of the NJ-series CPU Unit before you attempt to use it in a control sys- tem. Keep this manual in a safe place where it will be available for reference during operation. Intended Audience This manual is intended for the following personnel, who must also have knowledge of electrical sys- tems (an electrical engineer or the equivalent). • Personnel in charge of introducing FA systems. • Personnel in charge of designing FA systems. • Personnel in charge of installing and maintaining FA systems. • Personnel in charge of managing FA systems and facilities. For programming, this manual is intended for personnel who understand the programming language specifications in international standard IEC 61131-3 or Japanese standard JIS B3503. Applicable Products This manual covers the following products. CJ-series CJ1W-PRM21 PROFIBUS Master Unit CJ-series PROFIBUS Master Unit Operation Manual for NJ-series CPU Unit (W509) 1 Introduction Relevant Manuals There are three manuals that provide basic information on the NJ-series CPU Units: the NJ-series CPU Unit Hardware User’s Manual, the NJ-series CPU Unit Software User’s Manual and the NJ-series Instructions Reference Manual. -

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION to COSMOPOLITANISM AS CRITICAL and CREATIVE PRACTICE Eleanor Byrne and Berthold Schoene, Page 2

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO COSMOPOLITANISM AS CRITICAL AND CREATIVE PRACTICE Eleanor Byrne and Berthold Schoene, page 2 THE WORLD ON A TRAIN: GLOBAL NARRATION IN GEOFF RYMAN’S 253 Berthold Schoene, page 7 THE PRECARIOUS ECOLOGIES OF COSMOPOLITANISM Marsha Meskimmon, page 15 ‘HOW DARE YOU RUBBISH MY TOWN!’: PLACE LISTENING AS AN APPROACH TO SOCIALLY ENGAGED ART WITHIN UK URBAN REGENERATION CONTEXTS Elaine Speight, page 25 TOWARDS A COSMOPOLITAN CRITICALITY? RELATIONAL AESTHETICS, RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA AND TRANSNATIONAL ENCOUNTERS WITH PAD THAI Renate Dohmen, page 35 PARALLEL EDITING, MULTI-POSITIONALITY AND MAXIMALISM: COSMOPOLITAN EFFECTS AS EXPLORED IN SOME ART WORKS BY MELANIE JACKSON AND VIVIENNE DICK Rachel Garfield, page 46 OFFSHORE COSMOPOLITANISM: READING THE NATION IN RANA DASGUPTA’S TOKYO CANCELLED, LAWRENCE CHUA’S GOLD BY THE INCH AND ARAVIND ADIGA’S THE WHITE TIGER Liam Connell, page 60 TRICK QUESTIONS: COSMOPOLITAN HOSPITALITY Eleanor Byrne, page 68 GOOGLE PAINTINGS John Timberlake, page 78 Banner image: Maya Freelon Asante, Time Lapse, 2010, tissue paper sculpture, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Morton Fine Art, Washington, DC. www.mayafreelon.com. OPEN ARTS JOURNAL, ISSUE 1, SUMMER 2013 ISSN 2050-3679 www.openartsjournal.org 2 COSMOPOLITANISM AS Especially since 9/11 cosmopolitanism has asserted itself as a counterdiscursive response to globalisation CRITICAL AND CREATIVE and a critical methodology aimed at counterbalancing PRACTICE: the ongoing hegemony of what in The Cosmopolitan Vision Ulrich Beck has termed ‘the national outlook’. AN INTRODUCTION Invoking a world threatened by global risks Beck calls on communities to reconceive their nationalist Eleanor Byrne and Berthold Schoene, self-identification by opening up and contributing to Manchester Metropolitan University global culture with ‘[their] own language and cultural symbols’ (Beck, 2006, p.21). -

Master of All!

INFINITE WHONIVERSES- MASTER OF ALL! A SEQUEL TO Unity is Strength (INFERNO 3RD DOCTOR) “Once you start down the Dark Path, forever will it dominate your Destiny.”- Yoda- Star Wars- The Empire Strikes Back. 1 Prologue- The Panopticon on Gallifrey- There was uproar in the Panopticon as High Councillors vehemently argued with each other, the Lord High President left stunned and speechless as the news sank in. The Planet Earth in the 20th Century Timezone was gone, a burnt husk of a world, survivors few and scattered. There was incalculable damage to the Timeline. Two Timelords had been sent to investigate, to find out how it could have happened. Until then speculation and rumour brought disagreement and discontent to Gallifrey. Only a Timelord could cause such damage. While there were a few suspects, the two most likely candidates were Koschei of House Oakdown and The Doctor of House Lungbarrow, who had been exiled to Earth to prevent a number of invasions in that period. Had he failed? Whoever was responsible would be found and punished for the damage to the Web of Time. --- Koschei-Mordox-Skaara-Tre-Kordor of House Oakdown was no more, now he was THE MASTER OF AL L! He breathed deep, relishing his new body. The utter foolishness of the High Council would be their undoing. He grinned at the thought. The two emissaries, Borusa and Vancell had arrived to find him weak. The Alternate version of 2 himself had bungled the job of trying to kill him. He chuckled at the absurdity of the concept. -

A Study of Harry Smith's Master Work, Film No. 18 Mahagonny in Relation to the Brecht-Weil

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-6-2021 Appropriation of the Highest Order: A Study of Harry Smith’s Master Work, Film No. 18 Mahagonny in relation to the Brecht- Weill opera The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny and Duchamp’s The Large Glass Rose V. Marcus CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/723 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Appropriation of the Highest Order: A Study of Harry Smith’s Master Work, Film No. 18 Mahagonny in relation to the Brecht-Weill opera The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny and Duchamp’s The Large Glass by Rose Marcus Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2021 May 6, 2021 Lynda C. Klich Date Signature May 6, 2021 Maria Antonella Pelizzari Date Signature i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………….iii List of Illustrations…………………………………………………………………………..iv Introduction: Smith Himself………………………………………………………………………………...1 Chapter 1: Hall of Mirrors………………………………………………………………………………11 Chapter 2: Fourth Walls………………………………………………………………………………...25 Chapter 3: Failed Unfinished Shattered, More………………………………………………………….44 Conclusion: Smith Beyond Discussion……………………………………………. …………………...58 8. Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..62 9. Illustrations……………………………………………………………………………....67 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This paper came to fruition during what may be recognized as the year that led to the greatest awakenings in a generation. -

The Early Adventures - 5.4 the Crash of the Uk- 201 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE EARLY ADVENTURES - 5.4 THE CRASH OF THE UK- 201 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jonathan Morris | none | 31 Jan 2019 | Big Finish Productions Ltd | 9781781789667 | English | Maidenhead, United Kingdom The Early Adventures - 5.4 The Crash of the UK-201 PDF Book Textbook Stuff. View all Movies Sites. Some of these events are wonderful, some are tragic, but together they form our lives. First Doctor. The Black Hole. Series three saw the return of the First Doctor. Prev Post. Can she fix things so she gets back to the doctor. But it never made it. Steven , Sara. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Big Finish Originals. Short Trips 14 : The Solar System. The Dimension Cannon. You must be logged in to post a comment. Social connect: Login Login with twitter. Star Wars. Subscriber Short Trips. Cancel Save. Crashing on the planet Dido, a tragic chain of events was set in motion leading to the death of almost all of its crew and a massacre of the indigenous population. File:Domain of the Voord cover. The Eleventh Doctor Chronicles. Tales of Terror. The Scarifyers. Stockton Butler marked it as to-read Aug 31, Torchwood - Big Finish Audio. This has what seems to be a wonderful effect: the crew survives, the ship proceeds to arrive at the colony Astra, and Vicki goes on to live a long, happy life, first with her father and later with her husband and children. The baddies are a bit new series Doctor Who and would have been realised very differently in Tony rated it it was amazing May 31, For the first two stories, the role of Barbara Wright was recast, as Jacqueline Hill was deceased. -

Technologies Journal of Research Into New Media

Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies http://con.sagepub.com Doctor Who and the Convergence of Media: A Case Study in `Transmedia Storytelling' Neil Perryman Convergence 2008; 14; 21 DOI: 10.1177/1354856507084417 The online version of this article can be found at: http://con.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/14/1/21 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies can be found at: Email Alerts: http://con.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://con.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://con.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/14/1/21 Downloaded from http://con.sagepub.com by Roberto Igarza on December 6, 2008 021-039 084417 Perryman (D) 11/1/08 09:58 Page 21 Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies Copyright © 2008 Sage Publications London, Los Angeles, New Delhi and Singapore Vol 14(1): 21–39 ARTICLE DOI: 10.1177/1354856507084417 http://cvg.sagepub.com Doctor Who and the Convergence of Media A Case Study in ‘Transmedia Storytelling’ Neil Perryman University of Sunderland, UK Abstract / The British science fiction series Doctor Who embraces convergence culture on an unprecedented scale, with the BBC currently using the series to trial a plethora of new technol- ogies, including: mini-episodes on mobile phones, podcast commentaries, interactive red-button adventures, video blogs, companion programming, and ‘fake’ metatextual websites. In 2006 the BBC launched two spin-off series, Torchwood (aimed at an exclusively adult audience) and The Sarah Jane Smith Adventures (for 11–15-year-olds), and what was once regarded as an embarrass- ment to the Corporation now spans the media landscape as a multi-format colossus. -

Old Dominion University 2014-2019 Strategic Plan

2014–2019 STRATEGIC PLAN CONTENTS PREAMBLE:…………………………………………………………………..…...… 6 Mission Statement ………………………………………………………………….… 6 Vision Statement ……………………………………………………………………… 6 The University ……………………………………………………………………...… 6 INSTITUTIONAL ENVIRONMENT AND CONTEXT…………….……..….. 7 RECENT ACCOMPLISHMENTS: 2009-2014 ……………………………….... 8 EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM ACHIEVEMENTS…………………….… 8 Program Enhancement………………………………………….... 8 Entrepreneurship………………………………………………..... 9 Continuing Education and Professional Development…….… 9 ACCREDITATIONS AND PROGRAM RANKINGS………………….... 10 Distance Learning Programs……………………………………. 11 FACULTY QUALITY, RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION………..… 11 RESEARCH PROFILE AND AWARDS………………………………..… 12 Translational and Interdisciplinary Research………………... 13 New Initiatives………………………………………………….…. 14 ENROLLMENT MANAGEMENT…………………………………….…... 15 Recruitment…………………………………………………….….. 16 Distance Learning Expansion of Online Programming…….. 16 Student Success………………………………………………….... 17 Student Research and Awards…………………………………... 18 Military Connections………………………………………….….. 19 INTERNATIONALIZATION OF THE CURRICULUM…………….…. 19 Confucius Institute………………………………………….….…. 20 ATHLETICS……………………………………………………….……….... 20 2 Conference USA………………………………………………..…. 20 QUALITY OF UNIVERSITY LIFE …………………………………..…... 21 Service Standards…………………………………………..……... 21 Diversity and Inclusivity …………………………….…………... 21 Community Engagement……………………………..…………... 22 Environmentally Friendly ……………………………………….. 23 Civic Leadership…………………………………………………... 23 Campus Safety…………………………………………………….. -

Gallifrey: No

GALLIFREY: NO. 5 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Peaty,Una McCormack,David Llewellyn,Gary Russell,Sean Carlsen,Louise Jameson,Lalla Ward | none | 28 Feb 2013 | Big Finish Productions Ltd | 9781844359585 | English | Maidenhead, United Kingdom Gallifrey: No. 5 PDF Book As if she's fallen off a cliff. Arcadia , Gallifrey's "second city", was protected by a large number of sky trenches. Series 8. The War Doctor was present at the Fall of Arcadia , and it was there that he left his warning of "No More" for the combatants. Gallifrey had at least two large moons and a ring system, similar to Saturn in Earth 's solar system. Episode 3. What is Doctor Who? What did the Master do? TV : The Invasion of Time Rassilon later referred to the area that the barn in which the Doctor had slept as a child as the Drylands , claiming that no one of importance lived there. There's some sloppy exposition, revealing that The Fourth Doctor got stuck between times during his abduction and he has to sit this one out and some other sundries. The Tenth Doctor returned it to the time lock by shooting and destroying the diamond which connected Gallifrey to Earth. Share Tweet. Missy later told the Doctor that Gallifrey had returned to its original position. It was also called Gallifrey Original. I won't look. Wait, wait, wait, wait. Although these battles were stopped by Rassilon, the Death Zone remained and later became home to the Tomb of Rassilon. Doctor Who : Gallifrey stories. Basically The Third Doctor and Sarah Jane are traversing the Mountain to get to the Tomb when they come upon this guy, and there's nothing about him that doesn't suck. -

Summer Camp Song Book

Summer Camp Song Book 05-209-03/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Numbers 3 Short Neck Buzzards ..................................................................... 1 18 Wheels .............................................................................................. 2 A A Ram Sam Sam .................................................................................. 2 Ah Ta Ka Ta Nu Va .............................................................................. 3 Alive, Alert, Awake .............................................................................. 3 All You Et-A ........................................................................................... 3 Alligator is My Friend ......................................................................... 4 Aloutte ................................................................................................... 5 Aouettesky ........................................................................................... 5 Animal Fair ........................................................................................... 6 Annabelle ............................................................................................. 6 Ants Go Marching .............................................................................. 6 Around the World ............................................................................... 7 Auntie Monica ..................................................................................... 8 Austrian Went Yodeling ................................................................. -

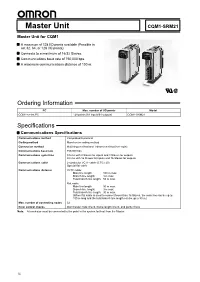

Master Unit CQM1-SRM21

Master Unit CQM1-SRM21 Master Unit for CQM1 A maximum of 128 I/O points available (Possible to set 32, 64, or 128 I/O points). Connects to a maximum of 16/32 Slaves. Communications baud rate of 750,000 bps. A maximum communications distance of 100 m. RC Ordering Information PC Max. number of I/O points Model CQM1-series PC 128 points (64 inputs/64 outputs) CQM1-SRM21 Specifications Communications Specifications Communications method CompoBus/S protocol Coding method Manchester coding method Connection method Multi-drop method and T-branch method (see note) Communications baud rate 750,000 bps Communications cycle time 0.5 ms with 8 Slaves for inputs and 8 Slaves for outputs 0.8 ms with 16 Slaves for inputs and 16 Slaves for outputs Communications cable 2-conductor VCTF cable (0.75 x 20) Special flat cable Communications distance VCTF cable: Main line length: 100 m max. Branch line length: 3 m max. Total branch line length: 50 m max. Flat cable: Main line length: 30 m max. Branch line length: 3 m max. Total branch line length: 30 m max. (When flat cable is used to connect fewer than 16 Slaves, the main line can be up to 100 m long and the total branch line length can be up to 50 m.) Max. number of connecting nodes 32 Error control checks Manchester code check, frame length check, and parity check Note: A terminator must be connected to the point in the system farthest from the Master. 14 CQM1-SRM21 CQM1-SRM21 Unit Specifications Current consumption 180 mA max. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Dust Breeding by Mike Tucker Doctor Who: Dust Breeding by Mike Tucker

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Dust Breeding by Mike Tucker Doctor Who: Dust Breeding by Mike Tucker. A Bad Quotation: " The girl from Perivale hits the jackpot again! " (Ace) The Terileptils, who created a sculpture placed in the Doctor's playroom, appeared as the main villains in the Fifth Doctor story The Visitation . The Doctor references the Fourth Doctor's City of Death when talking to Ace about the Mona Lisa. Bev Tarrant previously met the Seventh Doctor and Ace in The Genocide Machine . The Master's previously used aliases include Colonel Masters ( Terror of the Autons ) and Sir Gilles Estram ( The King's Demons ). The Master threatens to shrink Klemp to the size of a toy, referencing his tissue compression eliminator first used by "Colonel Masters" in Terror of the Autons . I'll Explain Later: The Master clearly disapproves of Madame Salvadori and her beguilement, as well as that of all of her guests, describing them as base peddlers of human misery and calling them uncivilised. How come this Master is so moral? This is the same incarnation who inhabited Nyssa's father Tremas, who would never have espoused such views. The Inquisitor's Judgement: Dust Breeding has a number of good ideas; the eeriest painting of human history being painted as a way for Munch to exorcise the screams of an alien life form in his head, the Master behind a bejewelled mask mixing with the corrupt upper echelons of society aboard an airborne art gallery, a planet with Daleks' screams echoing from the sands. Unfortunately the final script is too busy for its own good, with none of these ideas being given the focus or properly fleshed out.