Increasing Financial Flows for Urban Sanitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cordillera Energy Development: Car As A

LEGEND WATERSHED BOUNDARY N RIVERS CORDILLERACORDILLERA HYDRO ELECTRIC PLANT (EXISTING) HYDRO PROVINCE OF ELECTRIC PLANT ILOCOS NORTE (ON-GOING) ABULOG-APAYAO RIVER ENERGY MINI/SMALL-HYDRO PROVINCE OF ENERGY ELECTRIC PLANT APAYAO (PROPOSED) SALTAN B 24 M.W. PASIL B 20 M.W. PASIL C 22 M.W. DEVELOPMENT: PASIL D 17 M.W. DEVELOPMENT: CHICO RIVER TANUDAN D 27 M.W. PROVINCE OF ABRA CARCAR ASAS AA PROVINCE OF KALINGA TINGLAYAN B 21 M.W AMBURAYAN PROVINCE OF RIVER ISABELA MAJORMAJOR SIFFU-MALIG RIVER BAKUN AB 45 M.W MOUNTAIN PROVINCE NALATANG A BAKUN 29.8 M.W. 70 M.W. HYDROPOWERHYDROPOWER PROVINCE OF ILOCOS SUR AMBURAYAN C MAGAT RIVER 29.6 M.W. PROVINCE OF IFUGAO NAGUILIAN NALATANG B 45.4 M.W. RIVER PROVINCE OF (360 M.W.) LA UNION MAGAT PRODUCERPRODUCER AMBURAYAN A PROVINCE OF NUEVA VIZCAYA 33.8 M.W AGNO RIVER Dir. Juan B. Ngalob AMBUKLAO( 75 M.W.) PROVINCE OF BENGUET ARINGAY 10 50 10 20 30kms RIVER BINGA(100 M.W.) GRAPHICAL SCALE NEDA-CAR CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION SAN ROQUE(345 M.W.) POWER GENERATING BUED RIVER FACILITIES COMPOSED BY:NEDA-CAR/jvcjr REF: PCGS; NWRB; DENR DATE: 30 JANUARY 2002 FN: ENERGY PRESENTATIONPRESENTATION OUTLINEOUTLINE Î Concept of the Key Focus Area: A CAR RDP Component Î Regional Power Situation Î Development Challenges & Opportunities Î Development Prospects Î Regional Specific Concerns/ Issues Concept of the Key Focus Area: A CAR RDP Component Cordillera is envisioned to be a major hydropower producer in Northern Luzon. Car’s hydropower potential is estimated at 3,580 mw or 27% of the country’s potential. -

Baguio City, Philippines Area By

A Landslide Risk Rating System for the Baguio City, Philippines Area by Artessa Niccola D. Saldivar-Sali B.S., Civil Engineering (2002) University of the Philippines Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology MASSACHUSETTS INS E June 2004 OF TECHNOLOGY JUN 0 7 2004 0 2004 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved LIBRARIES Signature of Author ............................ Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering May 24, 2004 Certified by ............................................... / .................................. Herbert H. Einstein Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering /I A Thesis Supervisor Accepted by ........................... Heidi Nepf Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students BARKER A LANDSLIDE RISK RATING SYSTEM FOR THE BAGUIO CITY, PHILIPPINES AREA by ARTESSA NICCOLA D. SALDIVAR-SALI Submitted to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering on May 24, 2004 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Engineering in Civil and Environmental Engineering ABSTRACT This research formulates a LANDSLIDE RISK RATING SYSTEM for the Greater Baguio area in the Philippines. It is hoped that the tool will be made a part of the physical/urban planning process when used by engineers and planners and used to address risks posed by landslides given the rapidly increasing concentration of population and the development of infrastructure and industry in the Baguio area. Reports and studies of individual landslides in the area are reviewed in order to discover the causal factors of mass movements and their interactions. The findings of these research works are discussed in the first portion of this paper. -

DENR-BMB Atlas of Luzon Wetlands 17Sept14.Indd

Philippine Copyright © 2014 Biodiversity Management Bureau Department of Environment and Natural Resources This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the Copyright holder provided acknowledgement of the source is made. BMB - DENR Ninoy Aquino Parks and Wildlife Center Compound Quezon Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City Philippines 1101 Telefax (+632) 925-8950 [email protected] http://www.bmb.gov.ph ISBN 978-621-95016-2-0 Printed and bound in the Philippines First Printing: September 2014 Project Heads : Marlynn M. Mendoza and Joy M. Navarro GIS Mapping : Rej Winlove M. Bungabong Project Assistant : Patricia May Labitoria Design and Layout : Jerome Bonto Project Support : Ramsar Regional Center-East Asia Inland wetlands boundaries and their geographic locations are subject to actual ground verification and survey/ delineation. Administrative/political boundaries are approximate. If there are other wetland areas you know and are not reflected in this Atlas, please feel free to contact us. Recommended citation: Biodiversity Management Bureau-Department of Environment and Natural Resources. 2014. Atlas of Inland Wetlands in Mainland Luzon, Philippines. Quezon City. Published by: Biodiversity Management Bureau - Department of Environment and Natural Resources Candaba Swamp, Candaba, Pampanga Guiaya Argean Rej Winlove M. Bungabong M. Winlove Rej Dumacaa River, Tayabas, Quezon Jerome P. Bonto P. Jerome Laguna Lake, Laguna Zoisane Geam G. Lumbres G. Geam Zoisane -

Remote Sensing Application of the Geophysical Changes in the Coastlines and Rivers of Pangasinan, Philippines

REMOTE SENSING APPLICATION OF THE GEOPHYSICAL CHANGES IN THE COASTLINES AND RIVERS OF PANGASINAN, PHILIPPINES Annie Melinda Paz-Alberto, Marietta A. Pakaigue, Edmark P. Bulaong, Melissa Joy M. Sison, Ranilo B. Lao Institute for Climate Change and Environmental Management, Central Luzon State University, Science City of Muñoz, Nueva Ecija, 3120 Philippines Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] KEY WORDS: Accretion, Erosion, Fish pens/cages ABSTRACT The study aimed to determine the geophysical changes of the river outlets, riverbanks and coastlines in Bued- Angalacan and Alaminos, Pangasinan. Quantitative measurement and analysis were used in the detection of changes. Image analysis using remote sensing from the Satellite imageries of the Google Earth from years 2004 to 2014 were used. The actual measurements of the width and length of river outlets, riverbanks and coastlines of the said rivers were gathered by the use of South Total Station (NTS-362R6L) in September 2015. The insight of the residents regarding the feature changes of the river was obtained through one on one interview. Root Mean Square Errors (RMSE) were also computed for horizontal positioning and measurement to determine the accuracy of Google Earth Satellite Imageries. Results revealed that Bued-Angalacan and Alaminos river outlets decreased in width size due to natural factors and human activities. There was increased in size of the Bued-Angalacan and Alaminos riverbanks which could be possibly due to natural calamities and weak bank resistance brought about by the frequent flooding caused by heavy rains and the emergency released of water from San Roque Dam. -

NDCC Update Sitrep No. 19 Re TY Pepeng As of 10 Oct 12:00NN

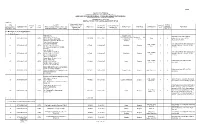

2 Pinili 1 139 695 Ilocos Sur 2 16 65 1 Marcos 2 16 65 La Union 35 1,902 9,164 1 Aringay 7 570 3,276 2 Bagullin 1 400 2,000 3 Bangar 3 226 1,249 4 Bauang 10 481 1,630 5 Caba 2 55 193 6 Luna 1 4 20 7 Pugo 3 49 212 8 Rosario 2 30 189 San 9 Fernand 2 10 43 o City San 10 1 14 48 Gabriel 11 San Juan 1 19 111 12 Sudipen 1 43 187 13 Tubao 1 1 6 Pangasinan 12 835 3,439 1 Asingan 5 114 458 2 Dagupan 1 96 356 3 Rosales 2 125 625 4 Tayug 4 500 2,000 • The figures above may continue to go up as reports are still coming from Regions I, II and III • There are now 299 reported casualties (Tab A) with the following breakdown: 184 Dead – 6 in Pangasinan, 1 in Ilocos Sur (drowned), 1 in Ilocos Norte (hypothermia), 34 in La Union, 133 in Benguet (landslide, suffocated secondary to encavement), 2 in Ifugao (landslide), 2 in Nueva Ecija, 1 in Quezon Province, and 4 in Camarines Sur 75 Injured - 1 in Kalinga, 73 in Benguet, and 1 in Ilocos Norte 40 Missing - 34 in Benguet, 1 in Ilocos Norte, and 5 in Pangasinan • A total of 20,263 houses were damaged with 1,794 totally and 18,469 partially damaged (Tab B) • There were reports of power outages/interruptions in Regions I, II, III and CAR. Government offices in Region I continue to be operational using generator sets. -

Annex - C Page 1 of 10

Annex - C Page 1 of 10 MINING TENEMENTS STATISTICS REPORT Regional Office: Cordillera Administrative Region As of : SEPTEMBER 2014 LIST OF MINERAL PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENT I. Approved and Registered TENEMENT ID CONTACT PERSON AREA D A T E REMARKS No. TENEMENT HOLDER LOCATION COMMODITY (MPSA NO.) AND ADDRESS (Has.) APPROVED EXPIRY Atty. Pablo T. Ayson, Jr., VP, Under commercial operation; 001-90-CAR Lepanto Consolidated Mining LCMC, BA-Lepanto Bldg., declaration of mining feasibility 1 (APSA No. Mankayan, Benguet 948.9700 Gold and Copper 03-Mar-1990 02-Mar-2015 Company 8747 Paseo de Roxas, project under review by MGB- 001) Makati City CO. Filed for Renewal Ronnie Siapno, President, 057-96-CAR Rm 11-2A, VGP Center, under 3rd term of exploration 2 (APSA No. Crescent Mining and Dev't. Corp. Mankayan, Benguet 534.0000 Gold,and Copper 12-Nov-1996 11-Nov-2021 6772 Ayala Ave., Makati City period 007) 1226 141-99-CAR James G. Beloy, President, Application for second renewal 3 (APSA No. Jabel Corporation Suite 3 3/F Jafer Bldg., 118 Baay-Licuan, Abra 297.0000 Gold, Silver 17-Dec-1999 16-Dec-2024 of exploration period under 058) West Ave., Quezon City process with MGB - CO Jeremias B. Beloy, Tuffaceous, 143-99-CAR Three-yr development & Abra Mining and Industrial Chairman, Suite 3 3/F Jafer Limestone, Silica 4 (APSA No. Bucay, Abra 672.0000 29-Dec-1999 28-Dec-2024 utilization program under Corporation Bldg., 118 West Ave., Sand 038) process with MGB - CAR Quezon City 144-99-CAR James G. Beloy, President, Gold, Silver, Under 2nd term of exploration 5 (APSA No. -

Uranium Division Pnoc Energy Companies Bldg. Pnpc

INIS-mf—9688 URANIUM DIVISION PNOC ENERGY COMPANIES BLDG. PNPC COMPLEX, MERRITT ROAD, FORT BONIFACIO, METRO MANILA PHILIPPINES fl I 1980 • • vlSE»mFIC ILfBftAR) ».»* URANIUM GEOCHEMICAL EXPLORATION ( IN NORTHWESTERN LUZON nCT13198* I 1 GABRIEL SANTOS, JR. AND LOURDES FERNANDEZ I PHILIPPINE ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION AND I MANUEL OGENA AND GEORGE TAULI PNOC-EDC . • • . I I ABS1HACT I A reconnaissani.. geochemical stream water and sediment survey • which was conducted in northwestern Luzon was able to detect '•. (10) uranium anomalous areas. These anomalous areas are located I along a north-south trending zone of Miocene marine elastics and sedimentary rocks with tuffaceous sediment intercalations. In § general, northwest Luzon has low radioactivity except for two anoira- - lous areas which have 3 to 6 times background radioactivity. Radon anomalies occur in sparsely scattered locations. The anomalous zones appear to be related to major north-s-. I faults and secondary northeast-southwest trending structures. .• - Geochemical corr jlations between uranium and other elements such as copper, lead, zinc, manganese, silver, cobalt, .and nickeJ I are generally very poor. I I I _ It is suggested that the intermediate intrusives iv the • Cordillera Central are possibly the principal source rodcs of W uranium in the survey area. r r i i i i i i i i i - 2 - i I I URANIUM GEOCHEMICAL EXPLORATION IN NORTHWESTERN LUZON • BY I GABRIEL SANTOS, JR. AND LOURDES FERNANDEZ I PHILIPPINE ATOMIC ENERGY (EMISSION AND I MANUEL OGENA AND GEORGE -TAULI PNOC-EDC I I INTRODUCTION I The first indication of possible uranium occurrences in • Solsona, Ilocos Norte, Northwestern Luzon was detected by an airborne gamma spectrometer survey which was carried out by I Huntings Geophysics, Lixl. -

(CAO) As of 05 February 2021

ACCOMMODATION ESTABLISHMENTS WITH CERTIFICATE OF AUTHORITY TO OPERATE (CAO) as of 05 February 2021 NAME OF ACCREDITATION CERTIFICATE OPERATIONAL QUARANTINE OPEN FOR ADDRESS CONTACT DETAILS CLASSIFICATION ESTABLISHMENT STATUS ISSUED STATUS FACILITY LEISURE CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION (CAR) BAGUIO CITY (074) 422-2075-76-80/ John Hay Special theforestlodge@campjohnhayhotel THE FOREST LODGE AT Economic Zone, Loakan s.ph/ Accredited 4 STAR HTL CAO OPEN No Yes CAMP JOHN HAY Road, Baguio City [email protected] h The Manor at Camp John THE MANOR AT CAMP (074) 424-0931 to 50/ Hay, Loakan Road, Accredited 4 STAR RES CAO OPEN No Yes JOHN HAY [email protected] Baguio City #1 J Felipe Street, (074) 619-0367/ HOTEL ELIZABETH Gibraltar Road, Baguio salesaccount2.baguio@hotelelizab Accredited 3 STAR HTL CAO OPEN No Yes BAGUIO City eth.com.ph #40 Bokawkan Rd., 09173981120/ (074) 442-3350/ Mabuhay PINE BREEZE COTTAGES Accredited CAO OPEN No Yes Baguio City [email protected] Accommodation #01 Apostol St., Corner (074) 442-1559/ 09176786874/ MINES VIEW PARK HOTEL Outlook Drive, Mines 09190660902/ Accredited Hotel CAO OPEN No Yes View, Baguio City [email protected] (074) 619-2050 (074) 442-7674/ Country Club Road, BAGUIO COUNTRY CLUB [email protected] Accredited 5 STAR Resort CAO OPEN No Yes Baguio City [email protected] [email protected] #37 Sepic St. Campo (074) 424-6092 (074) 620-3117/ NYC MANHATTAN HOTEL Accredited Hotel CAO OPEN No Yes Filipino, Baguio City [email protected] -

Project Brief May 2013 PROJECT OVERVIEW

Project Brief May 2013 PROJECT OVERVIEW De Los Reyes St., Outlook Drive, LOCATION Baguio City LAND AREA: 4,005.7 sqm TYPE OF DEVELOPMENT Mid-rise Building NUMBER OF BUILDINGS One (1) 6 Residential levels – North Wing 6 Residential levels – South Wing NUMBER OF FLOORS 2 Amenity Levels 3 Basement Parking Levels NUMBER OF 141 units RESIDENTIAL UNITS NUMBER OF 126 slots PARKING SLOTS UNIT SFA 6,933 sqm PARKING RATIO 89% How to get there: From Ben Palispis High-way Take Marcos Hi-way flyover heading down to Gov’t Park Road. Straight ahead towards Gov’t Center Road, turn right to T.M. Kalaw St. towards Upper Session Road, heading to South Drive. Upon reaching South drive, drive straight to reach Romulo Drive. Once in Romulo Drive, take a right turn at Outlook Drive. You’ll see a small street to your left named V. Delos Reyes St. Enter and drive down, Outlook Ridge will be to your right. From Kennon Road Take Military Cut-off Road heading towards South Drive. Upon reaching South drive, drive straight to reach Romulo Drive. Once in Romulo Drive, take a right turn at Outlook Drive. You’ll see a small street to your left named V. Delos Reyes St. Enter and drive down, Outlook Ridge will be to your right. KEY DISTANCES Schools Central Business District • Our Lady of the Atonement Cathedral - 3 Km • Berkley School - 2 Km • SM Baguio - 3 Km • Brent International School - 2 Km • Baguio Centermall - 3 Km • St. Louis University - 2 Km • Baguio Market - 3 Km • University of the Cordilleras - 2 Km • Burnham Park - 3 Km • University of Baguio - 2 Km • University -

A. Mining Tenement Applications 1

MPSA Republic of the Philippines Department of Environment and Natural Resources MINES AND GEOSCIENCES BUREAU - CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION MINING TENEMENTS STATISTICS REPORT FOR MONTH OF JULY 2021 MINERAL PRODUCTION SHARING AGREEMENT (MPSA) ANNEX-B %Ownership of Major SEQ HOLDER WITHIN PARCEL TEN Filipino and Foreign DATE FILED DATE APPROVED APPRVD (Integer no. of TENEMENT NO (Name, Authorized Representative with AREA (has.) MUNICIPALITY PROVINCE COMMODITY MINERAL REMARKS No. TYPE Person(s) with (mm/dd/yyyy) (mm/dd/yyyy) (T/F) TENEMENT NO) designation, Address, Contact details) RES. (T/F) Nationality A. Mining Tenement Applications 1. Under Process Shipside, Inc., Buguias, Beng.; With MAB - Case with Cordillera Atty. Pablo T. Ayson, Jr., Tinoc, Ifugao; Bauko Benguet & Mt. 49 APSA-0049-CAR APSA 4,131.0000 22-Dec-1994 Gold F F Exploration, Inc. formerly NPI Atty in fact, BA-Lepanto Bldg., & Tadian, Mt. Province (MGB Case No. 013) 8747 Paseo de Roxas, Makati City Province Jaime Paul Panganiban Wrenolph Panaganiban Case with EXPA No. 085 - with Court of Gold, Copper, 63 APSA-0063-CAR APSA Authorized Representative 85.7200 11-Aug-1997 Mankayan Benguet F F Appeals (Case No. C.A.-G.R. SP No. Silver AC 152, East Buyagan, La Trinidad, 127172) Benguet June Prill Brett James Wallace P. Brett, Jr. Case with EXPA No. 085 - with Court of Gold, Copper, 64 APSA-0064-CAR APSA Authorized Representative. 98.7200 11-Aug-1997 Mankayan Benguet F F Appeals (Case No. C.A.-G.R. SP No. Silver #1 Green Mansions Rd. 127172) Mines View Park, B.C. Itogon Suyoc Resoucres, Inc. -

Sitrep 09 Re TYP KIKO As of 15Aug

cascaded the mountain slope following a gulley which hit 3 miners’ camps adjacent the Liwliw Creek . The ten (10) small scale miners who responded and proceeded to the landslide site to conduct rescue operations were hit by another wave of landslide coming from the crest of Mt. Emerald Baguio City - 3 (Brgy Balsigan; Camp 8; and Camp 5) wherein the retaining wall along Brgy. City Camp Proper collapsed Nueva Ecija –1 ( along Maharlika Highway, Brgy. Putlan, Caranglan) Iloilo - 1 (Tubungan , Iloilo Province) due to damming of water in the mountain of Pinihakan Daraga resulting to flashflood with muds from Maslog and Jar-ed Rivers thereby, affecting 362 families/1,701 persons with 273 families/1,138 persons evacuated to 25 evacuation centers Negros Occidental – 1 (Sitio Manaol, Brgy San Quintin Remo, Moises Padilla) A ground movement of about 2 inches /15 minutes was observed with 700 hectares affected. A total of 65 families/325 persons were affected /evacuated to 12 evacuation centers. As per assessment of MGB VI, the mass movement in Brgy San Quintin Remo was caused by a combination of steep slopes, unconsolidated and muddy soil and rocks and the huge amount of water (rainwater and groundwater) in the landslide site. River Swelling /Overflowing – 5 CAR - Balili River in La Trinidad, Benguet and Abra River and other tributaries Region I -Bued River in Pangasinan Region IV-B - Busuanga River in Rizal, Occidental Mindoro ; and Mompong River in Sablayan, Occidental Mindoro in Region Breaching/Erosion of Earth Dikes and Sea wall– 10 Region I -Sea wall in Tabucolan, Santa, Ilocus Sur ; earthdike in Sison, Pangasinan ; dike in San Nicolas Pangasinan; ( 3) Region III –portions of Gumain River dike, Apalit earthdike and Porac earthdike collapsed ; and portions of Baluc dike was damaged due to 3 meters soil erosion all in Floridablanca; Arnedo dike in San Simon and Bucao dikes in Candaba all in Pampanga (7) II. -

Gold Mining in Benguet to 1898

philippine studies Ateneo de Manila University • Loyola Heights, Quezon City • 1108 Philippines Gold Mining in Benguet to 1898 Olivia M. Haban Philippine Studies vol. 48, no. 4 (2000): 455–487 Copyright © Ateneo de Manila University Philippine Studies is published by the Ateneo de Manila University. Contents may not be copied or sent via email or other means to multiple sites and posted to a listserv without the copyright holder’s written permission. Users may download and print articles for individual, noncom- mercial use only. However, unless prior permission has been obtained, you may not download an entire issue of a journal, or download multiple copies of articles. Please contact the publisher for any further use of this work at [email protected]. http://www.philippinestudies.net Fri June 27 13:30:20 2008 Gold Mining in Benguet to 1898 Olivia M. Habana The mining and trade of gold were among the most vital economic activities of the Ibaloy and Kankanay Igorots of Benguet province. Early Spanish chroniclers recorded a flourishing inter-Cordillera and lowland trade based on Igorot gold and Ilocano cloth and livestock. However, the inaccessibility of the region and the spirited resistance of the Igorots made the gold mines an elusive target. Throughout the Spanish period, numerous attempts were made to locate and exploit the Igorot gold mines but none of these succeeded. Benguet Igorot society was thus basically left to develop on its own. One of the most important consequences of this was the development of a native elite, the baknang, whose wealth and prestige were largely based on the ownership and control of the gold mines.