My Mind and Me

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors Richard Bass Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 38, No. 2. (Autumn, 1994), pp. 155-186. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-2909%28199423%2938%3A2%3C155%3AMOOAWI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-X Journal of Music Theory is currently published by Yale University Department of Music. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/yudm.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mon Jul 30 09:19:06 2007 MODELS OF OCTATONIC AND WHOLE-TONE INTERACTION: GEORGE CRUMB AND HIS PREDECESSORS Richard Bass A bifurcated view of pitch structure in early twentieth-century music has become more explicit in recent analytic writings. -

AP Music Theory Course Description Audio Files ”

MusIc Theory Course Description e ffective Fall 2 0 1 2 AP Course Descriptions are updated regularly. Please visit AP Central® (apcentral.collegeboard.org) to determine whether a more recent Course Description PDF is available. The College Board The College Board is a mission-driven not-for-profit organization that connects students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the College Board was created to expand access to higher education. Today, the membership association is made up of more than 5,900 of the world’s leading educational institutions and is dedicated to promoting excellence and equity in education. Each year, the College Board helps more than seven million students prepare for a successful transition to college through programs and services in college readiness and college success — including the SAT® and the Advanced Placement Program®. The organization also serves the education community through research and advocacy on behalf of students, educators, and schools. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.org. AP Equity and Access Policy The College Board strongly encourages educators to make equitable access a guiding principle for their AP programs by giving all willing and academically prepared students the opportunity to participate in AP. We encourage the elimination of barriers that restrict access to AP for students from ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups that have been traditionally underserved. Schools should make every effort to ensure their AP classes reflect the diversity of their student population. The College Board also believes that all students should have access to academically challenging course work before they enroll in AP classes, which can prepare them for AP success. -

Harmonic Dualism and the Origin of the Minor Triad

45 Harmonic Dualism and the Origin of the Minor Triad JOHN L. SNYDER "Harmonic Dualism" may be defined as a school of musical theoretical thought which holds that the minor triad has a natural origin different from that of the major triad, but of equal validity. Specifically, the term is associated with a group of nineteenth and early twentieth century theo rists, nearly all Germans, who believed that the minor harmony is constructed in a downward ("negative") fashion, while the major is an upward ("positive") construction. Al though some of these writers extended the dualistic approach to great lengths, applying it even to functional harmony, this article will be concerned primarily with the problem of the minor sonority, examining not only the premises and con clusions of the principal dualists, but also those of their followers and their critics. Prior to the rise of Romanticism, the minor triad had al ready been the subject of some theoretical speculation. Zarlino first considered the major and minor triads as en tities, finding them to be the result of harmonic and arith metic division of the fifth, respectively. Later, Giuseppe Tartini advanced his own novel explanation: he found that if one located a series of fundamentals such that a given pitch would appear successively as first, second, third •.• and sixth partial, the fundamentals of these harmonic series would outline a minor triad. l Tartini's discussion of combination tones is interesting in that, to put a root un der his minor triad outline, he proceeds as far as the 7:6 ratio, for the musical notation of which he had to invent a new accidental, the three-quarter-tone flat: IG. -

A Technical, Musical, and Historical Analysis of Frederic Chopin's

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection Undergraduate Scholarship 4-29-1996 A Technical, Musical, and Historical Analysis of Frederic Chopin’s Etudes, Op. 10 Henry Raymond Bauer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses Part of the Music Education Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Bauer, Henry Raymond, "A Technical, Musical, and Historical Analysis of Frederic Chopin’s Etudes, Op. 10" (1996). Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection. 244. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/ugtheses/244 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER UNIVERSITY HONORS PROGRAM Honors Thesis Certification Applicant t\e ..Y\..5' ~ fu Y D"ot\J l2vJ u t' f' \ (Name as It Is toappear on diploma) I,},/~ ~ Thesis title f\ Tech. n IQa L k \ (111 \ , g, Y"' A 1-\, 0 r "CA. \ i \ t\Y'\~\\{~\ ~ D-0 Frede .r-\L Cho~', r\~ E+uJe.-s J Opt> I~ Intended date of commencement t:k.\..i I \ \ \ '1'-9...l.....:!:(,~ _ Read and approved by: Thesis advlser(s) s:- ShYCfb Date Date , 1-1--7? Date Date Accepted and certified: / 5-J2-q7 Date For Honors Program use: Level of Honors conferred: University C_u_rn__L_a_u_d=-e= _ Departmental High Honors in Piano Pedag,Q,gy A TECHNICAL, MUSICAL, AND mSTORICAL ANALYSIS OF FREDERIC CHOPIN'S ElUDES, OP. 10 A Thesis Presented to the Department of Music Jordan College of Fine Arts and The Committee on Honors Butler University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Honors Henry Raymond Bauer April 29, 1996 L)) 1 10f ,8~# Preface b3g~ I began working on the Chopin Etudest Op. -

Chapter 28.5, the Diminished Seventh Chord in Modulation

598 THE COMPLETE MUSICIAN F. Write a progression in D minor in which the closing D tonic sounds more like a dominant than a tonic. (Hint: A Picardy third alone does not imply a reciprocal process.) G. Write a progression inC major that opens with a plagal progression, tonicizes E~ major, and closes in E~ major with a different plagal progression. The Diminished Seventh Chord and Enharmonic Modulation Beginning in the eighteenth century, composers used the diminished seventh chord both as a powerful goal-oriented applied chord and as a dramatic signpost. For example, a strategically placed diminished seventh chord could underscore a particularly emotional image from the text of a song. A vivid and painful example is heard in the last moment of Schubert's "Erlking." Immediately before we learn of the fate of the sick child ("and in [the father's] arms, the child ..."), the previous 145 measures of frantic, wildly galloping music come to a halt. The fermata that marks this moment, and which seems to last forever, is accompanied by a single sustained diminished seventh, underscoring this crucial moment (Example 28.8). We learn immediately thereafter that in spite of his valiant attempts to rush his sick son home by horseback, the father was too late: The child was dead. EXAMPLE 28.8 Schubert, "Erlkonig," D. 328 Even before the time of Bach, composers also used the diminished seventh chord to create tonal ambiguity. Ambiguity is possible because the chord in any of its inversions partitions the octave into four minor thirds (using enharmonicism). For example, given the diminished seventh chord in Example 28.9A, its three inversions produce no new intervals. -

Borrowed Chords

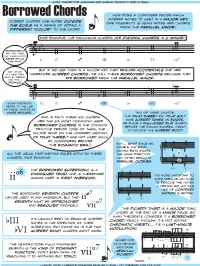

music theory for musicians and normal people by toby w. rush Borrowed Chords how does a composer decide which altered notes to use? in a major key, altered chords use notes outside one possibility is using notes and chords the scale as a means of adding a from the parallel minor. different “color” to the chord. for example, the following chords are diatonic chords in c minor: w “borrowed”? b w w why call them b w w w w nw that when major & b w w w w w never brings w w7 w 7 them back? c: ii° ii° III iv VI vii° but if we use them in a major key, they require and are hey, minor! accidentals I’ll have them therefore altered chords. we call these borrowed chords because they back by tuesday are from the this time, I borrowed parallel minor. promise! bw w w bw w & bw bw bbw bw b w Nw some theorists C: wii° ii°w7 III iv VI vii°7 refer to the use b b of these chords as mode mixture. two of these chords, and, in fact, these six chords the “flat three” and “flat six,” are the six most commonly used have altered tones as roots. we place a full-sized flat symbol borrowed chords in the common before the roman numeral itself practice period. (One of them, the to indicate this altered root. major triad on the lowered mediant, or “flat three,” was not used much by composers before wait... since we the romantic era.) why? double the root, ˙ ˙ moving both roots & b˙ ˙ all the usual part-writing rules apply to these the same direction 5 chords. -

Psychoacoustic Foundations of Contextual Harmonic Stability in Jazz Piano Voicings

Journal of Jazz Studies vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 156–191 (Fall 2011) Psychoacoustic Foundations Of Contextual Harmonic Stability In Jazz Piano Voicings James McGowan Considerable harmonic variation of both chord types and specific voicings is available to the jazz pianist, even when playing stable, tonic-functioned chords. Of course non-tonic chords also accommodate extensive harmonic variety, but they generally cannot provide structural stability beyond the musical surface. Many instances of tonic chords, however, also provide little or no sense of structural repose when found in the middle of a phrase or subjected to some other kind of “dissonance.” The inclusion of the word “stable” is therefore important, because while many sources are implicitly aware of the fundamental differences between stable and unstable chords, little significant work explicitly accounts for an impro- vising pianist’s harmonic options as associated specifically with harmonic stability— or harmonic “consonance”—in tonal jazz. The ramifications are profound, as the very question of what constitutes a stable tonic sonority in jazz suggests that underlying precepts of tonality function differ- ently in improvised jazz and common-practice music. While some jazz pedagogical publications attempt to account for the diverse chord types and specific voicings employed as tonic chords, these sources have not provided a distinct conceptual framework that explains what criteria link these harmonic options. Some music theorists, meanwhile, have provided valuable analytical models to account for the sense of resolution to stable harmonic entities. These models, however, are largely designed for “classical” music and are problematic in that they tend to explain pervasive non-triadic harmonies as aberrant in some way.1 1 Representative sources that address “classical” models of jazz harmony include Steve Larson, Analyzing Jazz: A Schenkerian Approach, Harmonologia: studies in music theory, no. -

Reharmonizing Chord Progressions

Reharmonizing Chord Progressions We’re going to spend a little bit of time talking about just a few of the techniques which you’ve already learned about, and how you can use these tools to add interest and movement into your own chord progressions. CHORD INVERSIONS If a song that you’re playing stays on the same chord for several beats, it can begin to sound stagnant if you play the same chord voicing over and over. One of the things you can do to add movement into the chord progression is to stay on the same chord but choose a different inversion of that chord. For instance, if you have 2 consecutive measures where the 1(Major) chord forms the harmony, try playing the first measure using 1 in root position and start the next measure by changing to a 1 over 3 (in other words, use a first inversion 1 chord). In modern chord notation, we’d write this as C/E. Or, if you don’t want to change the bass note– you can at least try using a different ‘voicing’ of the chord: instead of (from bottom to top note) C, G, E, C you might try C, C, G, E or C, G, E, G. For a guitarist, this may mean just playing the chord in a different position. For a keyboardist, you may have to consider which note names are doubled and whether the spacing between notes is closer or farther apart. SUBSTITUTE CHORDS OF SIMILAR QUALITY One of the things we’ve talked about previously is that certain chords in any given key sound ‘at rest’ and certain chords sound with a great deal of tension and feel like they ‘need to resolve’ to a place of rest. -

Course Name AP Music Theory

Course name: Level: Time Frame: AP Music Theory Advanced Placement 40 weeks Topic September – Elements of Pitch and Rhythm Essential Questions • What are the basic elements of pitch and rhythm that allow for understanding of music notation language? • What are the basic elements of pitch and rhythm that allow for horizontal and vertical music composition? • How are different scales, chords, and intervals developed and classified • How is sight-singing / ear-training important to developing a literate musician? • What is solfege and how is it useful in the music theory classroom? Enduring Understandings • Students will differentiate between different types of major and minor scales. • Students will understand and practice designation of proper key signatures • Students will compare major and relative minor key relationships • Students will comprehend and perform musical intervals • Students will practice solfege (moveable do system) with hand signs • Students will perform pentascales on piano while echoing patterns by teacher Alignment to NJCCS for Visual and Performing Arts AR.9-12.1.1.12 - [Standard] - All students will demonstrate an understanding of the elements and principles that govern the creation of works of art in dance, music, theatre, and visual art. AR.9-12.1.1.12.1 - [Content Statement] - Understanding nuanced stylistic differences among various genres of 0 music is a component of musical fluency. Meter, rhythm, tonality, and harmonics are determining factors in x the categorization of musical genres. AR.9-12.1.1.12.B.1 - [Cumulative Progress Indicator] - Examine how aspects of meter, rhythm, tonality, 0 intervals, chords, and harmonic progressions are organized and manipulated to establish unity and variety in x genres of musical compositions. -

An Analysis of the Chorales in Three Chopin Nocturnes

AN ANALYSIS OF THE CHORALES IN THREE CHOPIN NOCTURNES: OP. 32, NO.2; OP. 55, NO.1; AND THE NOCTURNE IN C# MINOR (WITHOUT OPUS NUMBER) by DAVID J. HEYER A THESIS Presented to the School ofMusic and Dance and the Graduate School ofthe University of Oregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master of Arts March 2008 11 "An Analysis ofthe Chorales in Three Chopin Nocturnes: Gp. 32, No.2; Gp. 55, No.1; and the Nocturne in C~ Minor (without opus number)," a thesis prepared by David J. Heyer in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master ofArts degree in the School of Music and Dance. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Dr. S~rson, Chair of the Examining Committee ~ /l'U /O~ Committee in Charge: Dr. Steve Larson, Chair Dr. Jack Boss Dr. Alexandre Dossin Accepted by: Dean of the Graduate School III © 2008 David J. Heyer .. IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of David J. Heyer for the degree of Master ofArts in the School of Music and Dance to be taken March 2008 Title: AN ANALYSIS OF THE CHORALES IN THREE CHOPIN NOCTURNES: OP. 32, NO.2; OP. 55, NO.1; AND THE NOCTURNE IN C~ MINOR (WITHOUT OPUS NUMBER) Approved: ----................ oo:=-::::=oo~-------------- Dr. Steve Larson Several of Chopin's nocturnes contain interesting chorales. This study discusses three such works-the Nocturnes in C~ Minor (without opus number), AI, Major (Op. 32, No.2), and F Minor (Op. 55, No.1). The chorales in the Nocturnes in C~ Minor and AI, Major are introductory. -

Graduate Diagnostic Examination in Music Theory

name: date: — Practice Test — University of Massachusetts Graduate Diagnostic Examination in Music Theory Make no marks on this page below this line area results Rudiments [1 point each] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Functional harmony [1 point each] 11 12 13 14 15 16 [4 points] 17 Form & compositional devices [4 points] 18 [2 points each] 19 20 21 2016 Practice version 1 (1) Write the pitch that is a perfect fifth (2) Write the pitch that is a minor (P5) below the given pitch. [1 point] seventh (m7) above the given pitch. [1 point] (3) Write an A-major triad in second (4) Write a B-major triad in first inversion. [1 point] inversion. [1 point] (5) Add accidentals to the upper three (6) Add accidentals to the upper three voices of the following chord to voices of the following chord to form a minor-minor seventh chord. form a half-diminished seventh Do not add any accidentals to the chord. bass note. [1 point] Do not add any accidentals to the bass note. [1 point] (7) Add three pitches above the given (8) Add three pitches above the given pitch to complete the given figured bass. pitch to complete the given figured bass. [1 point] [1 point] (9) Here is a pitch: Rewrite the pitch in each of the following clefs. Keep the pitch in the same octave. [1 point] (10) Here is an excerpt for Trumpet in Bf. This is the part the player reads. Rewrite the excerpt at concert pitch in the proper octave on the blank staff below. -

MTO 20.4: Johnston, Modal Idioms and Their Rhetorical Associations

Volume 20, Number 4, December 2014 Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory Modal Idioms and Their Rhetorical Associations in Rachmaninoff’s Works Blair Johnston NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.14.20.4/mto.14.20.4.johnston.php KEYWORDS: Rachmaninoff, harmony, neo-modalism, diatonic, equal-interval, rhetoric ABSTRACT: In this article, I examine passages from more than a dozen works by Rachmaninoff—especially the Third Symphony, op. 44—in order to better understand the significance that certain modal idioms (diatonic and equal-interval) have in his harmonic language and to show the consistency with which he treats these idioms across his oeuvre. I describe three types of diatonic modal idiom and three types of equal-interval modal idiom and I outline their basic rhetorical associations in Rachmaninoff’s music: diatonic modal idioms are consistently associated with introduction, exposition, digression, and post-climactic activity while equal-interval modal idioms are consistently associated with intensification, climax, and destabilization. I consider the implications those rhetorical associations have for the analysis of entire compositions, and, along the way, I suggest possible avenues for future research on Rachmaninoff ’s position within both the pan-European fin de siècle and the so-called Russian “silver age.” Received April 2014 1. Introduction by Way of an Introduction [1.1] Neo-modalism is an integral part of Rachmaninoff’s harmonic language. Passages that involve the familiar, named diatonic modes or the almost-as-familiar, named equal-interval modes (whole-tone, octatonic, hexatonic) appear in prominent locations in his works.