Reharmonizing Chord Progressions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Care and Feeding of the WHOLE MUSICAL YOU! Created by the Students and Instructors of the New Trier Jazz Ensembles Program

The Care and Feeding of the WHOLE MUSICAL YOU! Created by the students and instructors of the New Trier Jazz Ensembles Program The many domains of the whole musical you… TECHNICIAN LITERATE JAZZ MUSICIAN COMPOSER/ARRANGER IMPROVISER LISTENER CRITIC HISTORIAN PERFORMER Tools/resources needed to develop the whole musical you… desire goals time space guidance enjoyment DEVELOPING AS A TECHNICIAN Practice with a metronome Track your progress – make your assessment quantitative (numbers) Take small, measured steps Record yourself, and be critical (also be positive) Use SmartMusic as a scale-practicing companion Go bonkers with scales Be creative with scales (play scales in intervals, play scales through the entire range of your instrument, play scales starting on notes other than the tonic, remember that every scale also represents a chord for each note in that scale, find new patterns in your scales Challenge yourself – push your boundaries Use etudes and solo transcriptions to push yourself Use a metronome!!! DEVELOPING AS A LITERATE JAZZ MUSICIAN Practice sight-reading during every session Learn tunes (from the definitive recorded version when possible) Learn vocabulary Learn chords on the piano DEVELOPING AS A COMPOSER/ARRANGER Compose a melody Compose a chord progression Compose a melody on an established chord progression (called a contrafact) Re-harmonize an established melody Write an arrangement of an established melody DEVELOPING AS AN IMPROVISER Transcribe a solo Compose a solo for a tune you’re -

Harmony Crib Sheets

Jazz Harmony Primer General stuff There are two main types of harmony found in modern Western music: 1) Modal 2) Functional Modal harmony generally involves a static drone, riff or chord over which you have melodies with notes chosen from various scales. It’s common in rock, modern jazz and electronic dance music. It predates functional harmony, too. In some types of modal music – for example in jazz - you get different modes/chord scale sounds over the course of a piece. Chords and melodies can be drawn from these scales. This kind of harmony is suited to the guitar due to its open strings and retuning possibilities. We see the guitar take over as a songwriting instrument at about the same time as the modes become popular in pop music. Loop based music also encourages this kind of harmony. It has become very common in all areas of music since the late 20th century under the influence of rock and folk music, composers like Steve Reich, modal jazz pioneered by Miles Davis and John Coltrane, and influences from India, the Middle East and pre-classical Western music. Functional harmony is a development of the kind of harmony used by Bach and Mozart. Jazz up to around 1960 was primarily based on this kind of harmony, and jazz improvisation was concerned with the improvising over songs written by the classically trained songwriters and film composers of the era. These composers all played the piano, so in a sense functional harmony is piano harmony. It’s not really guitar shaped. When I talk about functional harmony I’ll mostly be talking about ways we can improvise and compose on pre-existing jazz standards rather than making up new progressions. -

Chapter 12 Answer Key.Indd

Chapter 12 Answer Key Applications Exercises 1. Spell and resolve dominant seventh chords in root position. Chord voic- ings should be either complete (C) or incomplete (IN), as indicated below the Roman numerals. © 2019 Taylor & Francis 2 Chapter 12 Answer Key 2. Spell and resolve inverted dominant seventh chords. All chords should be complete. Add any necessary inversion symbol to the tonic chord. 3. Spell and resolve leading-tone seventh chords in root position and inversion. Add any necessary inversion symbol to the tonic chord. © 2019 Taylor & Francis Chapter 12 Answer Key 3 4. Complete the following chord progression in four voices. Provide a syntactic analysis below the Roman numerals. The syntactic analysis is shown below the Roman numerals. The voicing of chords and voice leading between chords is variable. Brain Teaser What triad is shared by V7 and viiØ7? How do these two seventh chords differ in terms of their scale-degree contents? Answer: V7 and viiØ7 share the leading-tone triad (viiO). The two chords differ by 5ˆ (the root of V7) and 6ˆ (the seventh of viiØ7). 5ˆ and 6ˆ are a whole step apart (a half step in minor, where 6ˆ is the seventh of viiO7). Thinking Critically An incomplete triad or seventh chord is missing its fifth. Compared with other chord members (root, third, and seventh), why is it possible to omit the fifth (i.e., why is this particular chord member nonessential)? Discussion The root of a chord is necessary to identify the chord and its function, the third determines the quality of the chord (major or minor), and the seventh must be present for a chord to be an actual seventh chord (rather than a triad). -

Many of Us Are Familiar with Popular Major Chord Progressions Like I–IV–V–I

Many of us are familiar with popular major chord progressions like I–IV–V–I. Now it’s time to delve into the exciting world of minor chords. Minor scales give flavor and emotion to a song, adding a level of musical depth that can make a mediocre song moving and distinct from others. Because so many of our favorite songs are in major keys, those that are in minor keys1 can stand out, and some musical styles like rock or jazz thrive on complex minor scales and harmonic wizardry. Minor chord progressions generally contain richer harmonic possibilities than the typical major progressions. Minor key songs frequently modulate to major and back to minor. Sometimes the same chord can appear as major and minor in the very same song! But this heady harmonic mix is nothing to be afraid of. By the end of this article, you’ll not only understand how minor chords are made, but you’ll know some common minor chord progressions, how to write them, and how to use them in your own music. With enough listening practice, you’ll be able to recognize minor chord progressions in songs almost instantly! Table of Contents: 1. A Tale of Two Tonalities 2. Major or Minor? 3. Chords in Minor Scales 4. The Top 3 Chords in Minor Progressions 5. Exercises in Minor 6. Writing Your Own Minor Chord Progressions 7. Your Minor Journey 1 https://www.musical-u.com/learn/the-ultimate-guide-to-minor-keys A Tale of Two Tonalities Western music is dominated by two tonalities: major and minor. -

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors

Models of Octatonic and Whole-Tone Interaction: George Crumb and His Predecessors Richard Bass Journal of Music Theory, Vol. 38, No. 2. (Autumn, 1994), pp. 155-186. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0022-2909%28199423%2938%3A2%3C155%3AMOOAWI%3E2.0.CO%3B2-X Journal of Music Theory is currently published by Yale University Department of Music. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/yudm.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mon Jul 30 09:19:06 2007 MODELS OF OCTATONIC AND WHOLE-TONE INTERACTION: GEORGE CRUMB AND HIS PREDECESSORS Richard Bass A bifurcated view of pitch structure in early twentieth-century music has become more explicit in recent analytic writings. -

AP Music Theory Course Description Audio Files ”

MusIc Theory Course Description e ffective Fall 2 0 1 2 AP Course Descriptions are updated regularly. Please visit AP Central® (apcentral.collegeboard.org) to determine whether a more recent Course Description PDF is available. The College Board The College Board is a mission-driven not-for-profit organization that connects students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the College Board was created to expand access to higher education. Today, the membership association is made up of more than 5,900 of the world’s leading educational institutions and is dedicated to promoting excellence and equity in education. Each year, the College Board helps more than seven million students prepare for a successful transition to college through programs and services in college readiness and college success — including the SAT® and the Advanced Placement Program®. The organization also serves the education community through research and advocacy on behalf of students, educators, and schools. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.org. AP Equity and Access Policy The College Board strongly encourages educators to make equitable access a guiding principle for their AP programs by giving all willing and academically prepared students the opportunity to participate in AP. We encourage the elimination of barriers that restrict access to AP for students from ethnic, racial, and socioeconomic groups that have been traditionally underserved. Schools should make every effort to ensure their AP classes reflect the diversity of their student population. The College Board also believes that all students should have access to academically challenging course work before they enroll in AP classes, which can prepare them for AP success. -

Part One G Cadd9 Chord Fingerings

The Four Chord Secret to Playing Lots of Songs www.guitarlessonsforbeginnersonline.net Chord Fingerings: Part One G Cadd9 Chord Fingerings: Part Two D Em (E minor) © Guitar Mastery Solutions, Inc. Playing Chord Progressions A chord progression is a series of chords played one after the other. Most songs consist of several different chord progressions. Learning to play the chord progressions in this lesson will help you learn to play many different songs. Mastering the chord fingerings and chord progressions in this lesson will help you quickly learn to play many different songs in different styles of music. These fundamental chords are crucial to your development and improvement as a guitar player—learn them well and learn to change between them. You will use them for the rest of your guitar playing career! Chord Progression One Chords Used: D Cadd9 G Play four strums on each chord and change to the next: |D / / / |Cadd9 / / / |G / / / | (repeat) This chord progression is similar to the one used in the song “Can’t You See?” by the Marshall Tucker Band. Chord Progression Two Chords Used: D Cadd9 G This progression uses the same chords as the first one. The difference is that we will pick some of the notes in the first two chords and end with a strum on the final G chord. Key point to remember: Even though the pick hand is playing some single notes, your fret hand only needs to play the chord shapes, just like in Progression One. D Cadd9 G This chord progression and picking pattern is similar to the one used in the song “Sweet Home Alabama” by Lynyrd Skynyrd. -

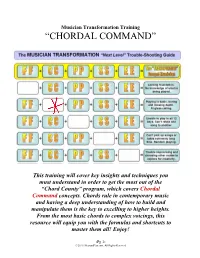

“Chordal Command”

Musician Transformation Training “CHORDAL COMMAND” This training will cover key insights and techniques you must understand in order to get the most out of the “Chord County” program, which covers Chordal Command concepts. Chords rule in contemporary music and having a deep understanding of how to build and manipulate them is the key to excelling to higher heights. From the most basic chords to complex voicings, this resource will equip you with the formulas and shortcuts to master them all! Enjoy! -Pg 1- © 2010. HearandPlay.com. All Rights Reserved Introduction In this guide, we’ll be starting with triads and what I call the “FANTASTIC FOUR.” Then we’ll move on to shortcuts that will help you master extended chords (the heart of contemporary playing). After that, we’ll discuss inversions (the key to multiplying your chordal vocaluary), primary vs secondary chords, and we’ll end on voicings and the difference between “voicings” and “inversions.” But first, let’s turn to some common problems musicians encounter when it comes to chordal mastery. Common Problems 1. Lack of chordal knowledge beyond triads: Musicians who fall into this category simply have never reached outside of the basic triads (major, minor, diminished, augmented) and are stuck playing the same chords they’ve always played. There is a mental block that almost prohibits them from learning and retaining new chords. Extra effort must be made to embrace new chords, no matter how difficult and unusual they are at first. Knowing the chord formulas and shortcuts that will turn any basic triad into an extended chord is the secret. -

Music Content Analysis : Key, Chord and Rhythm Tracking In

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS MUSIC CONTENT ANALYSIS : KEY, CHORD AND RHYTHM TRACKING IN ACOUSTIC SIGNALS ARUN SHENOY KOTA (B.Eng.(Computer Science), Mangalore University, India) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2004 Acknowledgments I am grateful to Dr. Wang Ye for extending an opportunity to pursue audio research and work on various aspects of music analysis, which has led to this dissertation. Through his ideas, support and enthusiastic supervision, he is in many ways directly responsible for much of the direction this work took. He has been the best advisor and teacher I could have wished for and it has been a joy to work with him. I would like to acknowledge Dr. Terence Sim for his support, in the role of a mentor, during my first term of graduate study and for our numerous technical and music theoretic discussions thereafter. He has also served as my thesis examiner along with Dr Mohan Kankanhalli. I greatly appreciate the valuable comments and suggestions given by them. Special thanks to Roshni for her contribution to my work through our numerous discussions and constructive arguments. She has also been a great source of practical information, as well as being happy to be the first to hear my outrage or glee at the day’s current events. There are a few special people in the audio community that I must acknowledge due to their importance in my work. -

Harmonic Dualism and the Origin of the Minor Triad

45 Harmonic Dualism and the Origin of the Minor Triad JOHN L. SNYDER "Harmonic Dualism" may be defined as a school of musical theoretical thought which holds that the minor triad has a natural origin different from that of the major triad, but of equal validity. Specifically, the term is associated with a group of nineteenth and early twentieth century theo rists, nearly all Germans, who believed that the minor harmony is constructed in a downward ("negative") fashion, while the major is an upward ("positive") construction. Al though some of these writers extended the dualistic approach to great lengths, applying it even to functional harmony, this article will be concerned primarily with the problem of the minor sonority, examining not only the premises and con clusions of the principal dualists, but also those of their followers and their critics. Prior to the rise of Romanticism, the minor triad had al ready been the subject of some theoretical speculation. Zarlino first considered the major and minor triads as en tities, finding them to be the result of harmonic and arith metic division of the fifth, respectively. Later, Giuseppe Tartini advanced his own novel explanation: he found that if one located a series of fundamentals such that a given pitch would appear successively as first, second, third •.• and sixth partial, the fundamentals of these harmonic series would outline a minor triad. l Tartini's discussion of combination tones is interesting in that, to put a root un der his minor triad outline, he proceeds as far as the 7:6 ratio, for the musical notation of which he had to invent a new accidental, the three-quarter-tone flat: IG. -

Seventh Chord Progressions in Major Keys

Seventh Chord Progressions In Major Keys In this lesson I am going to focus on all of the 7th chord types that are found in Major Keys. I am assuming that you have already gone through the previous lessons on creating chord progressions with basic triads in Major and Minor keys so I won't be going into all of the theory behind it like I did in those lessons. If you haven't read through those lessons AND you don't already have that knowledge under your belt, I suggest you download the FREE lesson PDF on Creating and Writing Major Key Chord Progressions at www.GuitarLessons365.com. So What Makes A Seventh Chord Different From A Triad? A Seventh Chord IS basically a triad with one more note added. If you remember how we can get the notes of a Major Triad by just figuring out the 1st, 3rd and 5th tones of a major scale then understanding that a Major Seventh Chord is a four note chord shouldn't be to hard to grasp. All we need to do is continue the process of skipping thirds to get our chord tones. So a Seventh Chord would be spelled 1st, 3rd, 5th and 7th. The added 7th scale degree is what gives it it's name. That is all it is. :) So what I have done for this theory lesson is just continue what we did with the basic triads, but this time made everything a Seventh Chord. This should just be a simple process of just memorizing each chord type to it's respective scale degree. -

A Proposal for the Inclusion of Jazz Theory Topics in the Undergraduate Music Theory Curriculum

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 8-2016 A Proposal for the Inclusion of Jazz Theory Topics in the Undergraduate Music Theory Curriculum Alexis Joy Smerdon University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Music Education Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Smerdon, Alexis Joy, "A Proposal for the Inclusion of Jazz Theory Topics in the Undergraduate Music Theory Curriculum. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2016. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/4076 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Alexis Joy Smerdon entitled "A Proposal for the Inclusion of Jazz Theory Topics in the Undergraduate Music Theory Curriculum." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Music, with a major in Music. Barbara A. Murphy, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Kenneth Stephenson, Alex van Duuren Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) A Proposal for the Inclusion of Jazz Theory Topics in the Undergraduate Music Theory Curriculum A Thesis Presented for the Master of Music Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Alexis Joy Smerdon August 2016 ii Copyright © 2016 by Alexis Joy Smerdon All rights reserved.