Specific Mood Symptoms Confer Risk for Subsequent Suicidal Ideation in Bipolar Disorder with and Without Suicide Attempt History: Multi-Wave Data from Step-Bd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Depression and Anxiety: a Review

DEPRESSION AND ANXIETY: A REVIEW Clifton Titcomb, MD OTR Medical Consultant Medical Director Hannover Life Reassurance Company of America Denver, CO [email protected] epression and anxiety are common problems Executive Summary This article reviews the in the population and are frequently encoun- overall spectrum of depressive and anxiety disor- tered in the underwriting environment. What D ders including major depressive disorder, chronic makes these conditions diffi cult to evaluate is the wide depression, minor depression, dysthymia and the range of fi ndings associated with the conditions and variety of anxiety disorders, with some special at- the signifi cant number of comorbid factors that come tention to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). into play in assessing the mortality risk associated It includes a review of the epidemiology and risk with them. Thus, more than with many other medical factors for each condition. Some of the rating conditions, there is a true “art” to evaluating the risk scales that can be used to assess the severity of associated with anxiety and depression. Underwriters depression are discussed. The various forms of really need to understand and synthesize all of the therapy for depression are reviewed, including key elements contributing to outcomes and develop the overall therapeutic philosophy, rationale a composite picture for each individual to adequately for the choice of different medications, the usual assess the mortality risk. duration of treatment, causes for resistance to therapy, and the alternative approaches that The Spectrum of Depression may be employed in those situations where re- Depression represents a spectrum from dysthymia to sistance occurs. -

Psychomotor Retardation Is a Scar of Past Depressive Episodes, Revealed by Simple Cognitive Tests

European Neuropsychopharmacology (2014) 24, 1630–1640 www.elsevier.com/locate/euroneuro Psychomotor retardation is a scar of past depressive episodes, revealed by simple cognitive tests P. Gorwooda,b,n,S.Richard-Devantoyc,F.Bayléd, M.L. Cléry-Meluna aCMME (Groupe Hospitalier Sainte-Anne), Université Paris Descartes, Paris, France bINSERM U894, Centre of Psychiatry and Neurosciences, Paris 75014, France cDepartment of Psychiatry and Douglas Mental Health University Institute, McGill Group for Suicide Studies, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada dSHU (Groupe Hospitalier Sainte-Anne), 7 rue Cabanis, Paris 75014, France Received 25 March 2014; received in revised form 24 July 2014; accepted 26 July 2014 KEYWORDS Abstract Cognition; The cumulative duration of depressive episodes, and their repetition, has a detrimental effect on Major depressive depression recurrence rates and the chances of antidepressant response, and even increases the risk disorder; of dementia, raising the possibility that depressive episodes could be neurotoxic. Psychomotor Recurrence; retardation could constitute a marker of this negative burden of past depressive episodes, with Psychomotor conflicting findings according to the use of clinical versus cognitive assessments. We assessed the role retardation; of the Retardation Depressive Scale (filled in by the clinician) and the time required to perform the Scar; Neurotoxic neurocognitive d2 attention test and the Trail Making Test (performed by patients) in a sample of 2048 depressed outpatients, before and after 6 to 8 weeks of treatment with agomelatine. From this sample, 1140 patients performed the TMT-A and -B, and 508 performed the d2 test, at baseline and after treatment. At baseline, we found that with more past depressive episodes patients had more severe clinical level of psychomotor retardation, and that they needed more time to perform both d2 and TMT. -

Understanding the Mental Status Examination with the Help of Videos

Understanding the Mental Status Examination with the help of videos Dr. Anvesh Roy Psychiatry Resident, University of Toronto Introduction • The mental status examination describes the sum total of the examiner’s observations and impressions of the psychiatric patient at the time of the interview. • Whereas the patient's history remains stable, the patient's mental status can change from day to day or hour to hour. • Even when a patient is mute, is incoherent, or refuses to answer questions, the clinician can obtain a wealth of information through careful observation. Outline for the Mental Status Examination • Appearance • Overt behavior • Attitude • Speech • Mood and affect • Thinking – a. Form – b. Content • Perceptions • Sensorium – a. Alertness – b. Orientation (person, place, time) – c. Concentration – d. Memory (immediate, recent, long term) – e. Calculations – f. Fund of knowledge – g. Abstract reasoning • Insight • Judgment Appearance • Examples of items in the appearance category include body type, posture, poise, clothes, grooming, hair, and nails. • Common terms used to describe appearance are healthy, sickly, ill at ease, looks older/younger than stated age, disheveled, childlike, and bizarre. • Signs of anxiety are noted: moist hands, perspiring forehead, tense posture and wide eyes. Appearance Example (from Psychosis video) • The pt. is a 23 y.o male who appears his age. There is poor grooming and personal hygiene evidenced by foul body odor and long unkempt hair. The pt. is wearing a worn T-Shirt with an odd symbol looking like a shield. This appears to be related to his delusions that he needs ‘antivirus’ protection from people who can access his mind. -

Mental Health and PD

Mental Health and PD Laura Marsh, MD Director, Mental Health Care Line Michael E. DeBakey Medical Center Professor of Psychiatry and Neurology Baylor College of Medicine Recorded on September 18, 2018 Disclosures Research Support Parkinson’s Foundation, Dystonia Foundation, Veterans Health Admin Consultancies (< 2 years) None Honoraria None Royalties Taylor & Francis/Informa Approved/Unapproved Uses Dr. Marsh does intend to discuss the use of off-label /unapproved use of drugs or devices for treatment of psychiatric disturbances in Parkinson’s disease. 1 Learning Objectives • Describe relationships between motor, cognitive, and psychiatric dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease (PD) over the course of the disease. • List the common psychiatric diagnoses seen in patients with PD. • Describe appropriate treatments for neuropsychiatric disturbances in PD. 2 James Parkinson 1755 - 1828 “Involuntary tremulous motion, with lessened muscular power, In parts not in action and even when supported; with a propensity to bend the trunk forward, and to pass from a walking to a running pace; … 3 James Parkinson 1755 - 1828 “Involuntary tremulous motion, with lessened muscular power, In parts not in action and even when supported; with a propensity to bend the trunk forward, and to pass from a walking to a running pace; the senses and intellects being uninjured.” 4 The Complex Face of Parkinson’s Disease • Affects ~ 0.3% general population ~ 1.5 million Americans, 7-10 Million globally ~ 1% population over age 50; ~ 2.5% > 70 years; ~ 4% > 80 years ~ All -

Sample Psychiatry Questions & Critiques

Sample Psychiatry Questions & Critiques Sample Psychiatry Questions & Critiques The sample NCCPA items and item critiques are provided to help PAs better understand how exam questions are developed and should be answered for NCCPA’s Psychiatry CAQ exam. Question #1 A 50-year-old woman who has been treated with sertraline for major depressive disorder for more than two years comes to the office because she has had weakness, cold intolerance, constipation, and weight gain during the past six months. Physical examination shows dry, coarse skin as well as bradycardia, hypothermia, andswelling of the hands and feet. Which of the following laboratory studies is the most appropriate to determine the diagnosis? (A) Liver function testing (B) Measurement of serum electrolyte levels (C) Measurement of serum estrogen level (D) Measurement of serum sertraline level (E) Measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone level Content Area: Depressive Disorders (14%) Critique This question tests the examinee’s ability to determine the laboratory study that is most likely to specify the diagnosis. The correct answer is Option (E), measurement of serum thyroid- stimulating hormone level. Hypothyroidism is suspected on the basis of the patient’s symptoms of depression, weakness, constipation, and weight gain as well as the physical findings of bradycardia, hypothermia, swelling of the hands and feet, and dry, coarse skin. Measurement of serum thyroid-stimulating hormone level is the study that will either confirm or refute this suspected diagnosis. ©NCCPA. 2021. All rights reserved. Sample Psychiatry Questions & Critiques Option (A), liver function testing, is a plausible choice based on the patient’s signs and symptoms of weakness, weight gain, and swelling of the hands and feet. -

Psychomotor Retardation and the Prognosis of Antidepressant Treatment in Patients with Unipolar Psychotic Depression

Journal of Psychiatric Research 130 (2020) 321–326 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Psychiatric Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jpsychires Psychomotor Retardation and the prognosis of antidepressant treatment in patients with unipolar Psychotic Depression Joost G.E. Janzing a,*, Tom K. Birkenhager¨ b, Walter W. van den Broek b, Leonie M.T. Breteler c, Willem A. Nolen d, Robbert-Jan Verkes a a Department of Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Radboudumc, Nijmegen, the Netherlands b Department of Psychiatry Erasmus University Medical Centre, Rotterdam, the Netherlands c Department of Psychiatry, St. Antonius-Mesos Hospital, Utrecht, the Netherlands d Department of Psychiatry, University Medical Center Groningen, the Netherlands ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Background: Psychomotor Retardation is a key symptom of Major Depressive Disorder. According to the literature Antidepressive agents its presence may affect the prognosis of treatment. Aim of the present study is to investigate the prognostic role of Affective disorders Psychomotor Retardation in patients with unipolar Psychotic Depression who are under antidepressant Psychotic treatment. Depression Methods: The Salpetriere Retardation Rating Scale was administered at baseline and after 6 weeks to 122 patients Drug therapy Psychomotor retardation with unipolar Psychotic Depression who were randomly allocated to treatment with imipramine, venlafaxine or venlafaxine plus quetiapine. We studied the effects of Psychomotor Retardation on both depression and psychosis related outcome measures. Results: 73% of the patients had Psychomotor Retardation at baseline against 35% after six weeks of treatment. The presence of Psychomotor Retardation predicted lower depression remission rates in addition to a higher persistence of delusions. After six weeks of treatment, venlafaxine was associated with higher levels of Psy chomotor Retardation compared to imipramine and venlafaxine plus quetiapine. -

Psychomotor Retardation and the Prognosis of Antidepressant Treatment in Patients with Unipolar Psychotic Depression Janzing, Joost G

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Psychomotor Retardation and the prognosis of antidepressant treatment in patients with unipolar Psychotic Depression Janzing, Joost G. E.; Birkenhager, Tom K.; van den Broek, Walter W.; Breteler, Leonie M. T.; Nolen, Willem A.; Verkes, Robbert-Jan Published in: Journal of Psychiatric Research DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.020 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2020 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Janzing, J. G. E., Birkenhager, T. K., van den Broek, W. W., Breteler, L. M. T., Nolen, W. A., & Verkes, R-J. (2020). Psychomotor Retardation and the prognosis of antidepressant treatment in patients with unipolar Psychotic Depression. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 130, 321-326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.07.020 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. -

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders

The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines World Health Organization -1- Preface In the early 1960s, the Mental Health Programme of the World Health Organization (WHO) became actively engaged in a programme aiming to improve the diagnosis and classification of mental disorders. At that time, WHO convened a series of meetings to review knowledge, actively involving representatives of different disciplines, various schools of thought in psychiatry, and all parts of the world in the programme. It stimulated and conducted research on criteria for classification and for reliability of diagnosis, and produced and promulgated procedures for joint rating of videotaped interviews and other useful research methods. Numerous proposals to improve the classification of mental disorders resulted from the extensive consultation process, and these were used in drafting the Eighth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-8). A glossary defining each category of mental disorder in ICD-8 was also developed. The programme activities also resulted in the establishment of a network of individuals and centres who continued to work on issues related to the improvement of psychiatric classification (1, 2). The 1970s saw further growth of interest in improving psychiatric classification worldwide. Expansion of international contacts, the undertaking of several international collaborative studies, and the availability of new treatments all contributed to this trend. Several national psychiatric bodies encouraged the development of specific criteria for classification in order to improve diagnostic reliability. In particular, the American Psychiatric Association developed and promulgated its Third Revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, which incorporated operational criteria into its classification system. -

Delirium Assessment: Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) 3D-CAM

Delirium Assessment: Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) 3D-CAM Edward R. Marcantonio, M.D., S.M. Professor of Medicine Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center Harvard Medical School 1 Delirium Measurement in Research Studies • One size does NOT fit all • Considerations: – What kind of assessment to use? – How to determine delirium presence, severity? – Who should perform the assessments? – How often to perform the assessments? • Answer may differ from study to study Bedside assessment in Epi Studies • Not making a clinical diagnosis • Making a research assignment of delirium presence or absence • Goals: – High validity: concordance with external standard – High reliability: concordance with each other Standardized Delirium Tests (selected from >40) • Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) • CAM for the Intensive Care Unit (CAM-ICU) • 3-Minute Diagnostic Interview for CAM delirium (3D-CAM) • Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist (ICDSC) • Delirium Index (DI) • Delirium Observation Screening Scale (DOSS) • Delirium Rating Scale (DRS)-Revised-98 • Delirium Symptom Interview (DSI) • Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) • Neelon/Champagne Confusion Scale (NEECHAM) • Nursing Delirium Screening Scale (NuDESC) • The 4AT ….and more 5 Focus on Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) • Most widely used method worldwide • Used in >5000 original studies to date, translated into over 20 languages • Short CAM (4-item)—diagnostic algorithm only • Long CAM (10-item): – provides more information on phenotypes, severity – can serve as reference standard in research studies • Our training today will focus on the Long CAM • Also describe the 3D CAM--standardized interview that operationalizes the Short CAM 6 Confusion Assessment Method • Developed in 1988, since no validated instrument for delirium existed at that time • Designed to enable non-psychiatrist clinicians to detect delirium quickly and accurately • Based on DSM-IIIR criteria (11 criteria)—simplified and operationalized criteria and developed diagnostic algorithm. -

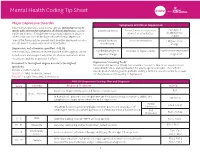

Mental Health Coding Tip Sheet

Mental Health Coding Tip Sheet Major Depressive Disorder Symptoms of Clinical Depression Patients that experience a depressive episode lasting two or more weeks with at least five symptoms of clinical depression causing *Depressed Mood *Loss of interest or pleasure Feelings of significant distress or impairment not aused by substance abuse or in most or all activities worthlessness other condityion that can be diagnosed with clinical depression.1 or guilt *One of the five symptoms present must be either depressed mood or Suicidal ideations Poor concentration Fatigue or low loss of interest or pleasure in most or all activities. or self-harm energy Depression, not otherwise specified - F32.92 The condition is often more severe than the code suggests. Avoid Significant weight or Insomnia or hypersomnia Psychomotor retardation broad terms and unspecified codes for a better awareness about appetite change or agitation the disease and the population it affects. 3 Document to the highest degree & code to the highest Depression Screening Tools Mental Health America (MHA) has a number resources that focus on prevention, specificity early identification, and intervention for adults age 18 and older. The PHQ-9© Include condition details questionnaire4 can be given to patients during a primary care encounter to screen SEVERITY - Mild, Moderate, Severe for the presence and severity of depression. EPISODE - Single, Recurrent, In Remission PHQ-9© Depression Scoring, Plan and Diagnosis Score Severity Proposed Treatment ICD-10 None: not depressed/no personal history of depression. N/A 0 - 4 None - Minimal In Remission*: patient is receiving treatment for depression but condition is stable and See Below symptoms no longer meet criteria for major depression. -

Olanzapine in Treatment of Patients with Bipolar 1 Disorder and Panic Comorbidity: a Case Study

Olanzapine in Treatment of Patients With Bipolar 1 Disorder And Panic Comorbidity: A Case Study Lilijana Oru~1, Semra ^avaljuga2 1 Psychiatric Clinic, Clinical Centre University of Sarajevo 2 Institute of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Sarajevo Abstract itive effects on the anxiety symptoms in various psychi- atric conditions and in GAD were reported. Anxiety disorders are frequently co-morbid with bipolar In this paper we describe two cases of BP1 disorder fol- disorders (BP). Anxiety symptoms can have a great lowed by panic symptoms treated with olanzapine at impact on course of illness and patient's quality of life. Psychiatric Clinic, Clinical Center University of Olanzapine is the first antipsychotic approved as a mood Sarajevo. stabilizing agent. In this paper two cases of BP 1 disorder where panic attacks co-occur treated with olanzapine Case 1. were presented. In both cases olanzapine showed very good effects in treatment of panic symptoms within the A female patient, 25 years old, single, clerk, was admit- course of BP disorder. ted at our inpatient department three years ago. She suf- fered from severe depression followed by psychomotor Key words: bipolar disorder, anxiety disorder, panic agitation, felling of worthlessness, delusions of guilt and attacks, comorbidity, olanzapine hypochondriac delusion (she was convinced that she has a lethal communicable disease she spread around). The Introduction patient lost 10kg within one month due to the loss of appetite. Recurrent thoughts of death and very intensive A growing literature suggests that anxiety disorders fre- suicidal ideation were prominent in her clinical picture. quently overlap with mood disorders (e.g. -

Mood Disorders

Mood Disorders Office of Forensic Mental Health Services August 27, 2020 Presented by: Erik Knudson Objectives People will learn: • Definition of mood disorder • Types of mood disorders • Symptoms of mood disorders • Diagnostic criteria of different mood disorders Mood Disorders Mood disorders are conditions where mood is primary, the predominant problem. Mood vs. Affect Mood Affect • A sustained emotional attitude • The way a patient’s emotional • Typically garnered through the state is conveyed patient’s self-report • Relates more to others’ perception of the patient’s emotional state, responsiveness Mood Disorders • Major Depressive Disorder • Dysthymic Disorder • Depressive Disorder NOS • Bipolar I Disorder • Bipolar II Disorder • Cyclothymic Disorder • Bipolar Disorder NOS • Mood Disorder - general medical condition • Substance-Induced Mood Disorder • Mood Disorder NOS Differentiating Anxiety and Depression Anxiety Depression • Difficulty falling asleep • Early awakening • Tremor or palpitations or oversleeping • Hot or cold flushes • Agitation • Faintness or dizziness • Loss of libido • Muscle tension • Sadness, despair • Helplessness • Hopelessness, guilt • Apprehension • Lack of motivation • Catastrophic thinking • Anhedonia, apathy • Easily startled • Slow speech and thought • Avoidance of feared • Suicidal thoughts situations • Decreased socialization Symptoms Common to Anxiety and Depression • Sleep disturbance • Rapid mood swings • Appetite change • Difficulty concentrating • Fatigue • Indecision • Restlessness • Decreased